Current Developments in European Alcohol Policy: An Analysis of Possible Impacts on the German Wine Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Provide improved information to consumers;

- Restricting alcohol advertising and sponsorship activities;

- Revise pricing, including consideration of increasing taxes on alcoholic beverages.

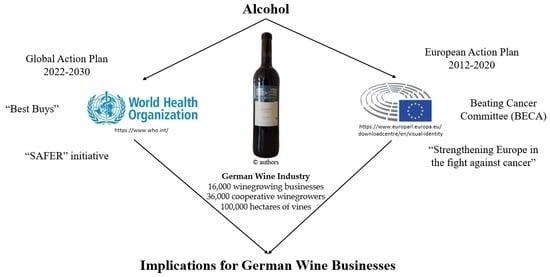

2. Global and European Alcohol Policy

2.1. Global Alcohol Consumption and Its Regulation

- Bans on advertising, which should apply to various forms of media;

- Tax increases combined with measures to curb tax avoidance;

- Restriction of the availability of alcoholic beverages, e.g., by adjusting sales hours.

2.2. The Development of Scientifically Informed Alcohol Policy

2.3. Alcohol Consumption in the European Union and Its Regulation

2.4. The Influence of Cultural Factors on European Alcohol Policy

3. Limiting Influences on EU Alcohol Policy

3.1. The Scientific Discourse on the Harmfulness of Alcoholic Beverages

3.2. The Scientific Discourse on the Effectiveness of Alcohol Policy Measures

3.3. Lack of Political Initiative and Legal Barriers

4. Discussion of Implications for the German Wine Industry

4.1. Wine as a “Sin Product”

4.2. Different Influences on Different Alcoholic Beverages

4.3. Influence on the Suppliers’ Assortments

4.4. Obstacles for the German Wine Industry

5. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OIV. State of the World Vitivinicultural Sector in 2020. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/7909/oiv-state-of-the-world-vitivinicultural-sector-in-2020.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Richter, B.; Hanf, J.H. Analyse des Wettbewerbsumfelds aus Sicht der deutschen Winzergenossenschaften. Ber. Über Landwirtsch. Z. Für Agrarpolit. Und Landwirtsch. Aktuelle Beiträge 2021, 99, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsches Weininstitut. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2021/2022. Available online: https://www.deutscheweine.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Website/Service/Downloads/Statistik_2021-2022.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Unsesco. Weinkultur in Deutschland. Available online: https://www.unesco.de/kultur-und-natur/immaterielles-kulturerbe/immaterielles-kulturerbe-deutschland/weinkultur (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Deckers, D. Wein: Geschichte und Genuss; Verlag C. H. Beck: Munich, Germany, 2017; ISBN 9783406711145. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Strengthening Europe in the Fight against Cancer: European Parliament Resolution of 16 February 2022 on Strengthening Europe in the Fight Against Cancer—Towards a Comprehensive and Coordinated Strategy (2020/2267(INI)). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0038_EN.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- European Parliament. Working Document on Inputs of the Special Committee on Beating Cancer (BECA) to Influence the Future Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/BECA-DT-660088_EN.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- European Parliament. Outcome, Work and Activities of the Special Committee on Beating Cancer: September 2020–December 2021—An Overview. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/246543/BECA_Compendium_final_lr.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- European Parliament. Report on Strengthening Europe in the Fight against Cancer—Towards a Comprehensive and Coordinated Strategy (2020/2267(INI)). A9-0001/2022. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2022-0001_EN.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Kamm, C. EU-Ausschuss Fordert Schockbilder auf Weinflaschen. Available online: https://www.rheinpfalz.de/lokal/pfalz-ticker_artikel,-eu-ausschuss-fordert-schockbilder-auf-weinflaschen-_arid,5304612.html (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Kopp, C. Künftig Warnhinweise auf Weinflaschen? Available online: https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/wein-etiketten-warnhinweis-winzer-101.html (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- SWR. Winzer Aus RLP Fürchten Sich Vor Entscheidung der EU-Kommission. Available online: https://www.swr.de/swraktuell/rheinland-pfalz/eu-erwaegt-warnhinweise-auf-weinflaschen-100.html (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Griswold, M.G.; Fullman, N.; Hawley, C.; Arian, N.; Zimsen, S.R.M.; Tymeson, H.D.; Venkateswaran, V.; Tapp, A.D.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Salama, J.S.; et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Parliament. Report on Strengthening EUROPE in the Fight Against Cancer—Towards a Comprehensive and Coordinated Strategy: Amendments 033-037. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2022-0001-AM-033-037_EN.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:8dec84ce-66df-11eb-aeb5-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-92-4-156563-9. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Information System on Alcohol and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/global-information-system-on-alcohol-and-health (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- OECD. Tackling Harmful Alcohol Use: Economics and Public Health Policy; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015; ISBN 978-92-64-18106-9. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Preventing Harmful Alcohol Use; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; ISBN 978-92-64-48558-7. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; ISBN 978 92 4 159993 1. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler, D.; Mckee, M.; Ebrahim, S.; Basu, S. Manufacturing epidemics: The role of global producers in increased consumption of unhealthy commodities including processed foods, alcohol, and tobacco. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WHO. Thirty-Sixth World Health Assembly: Resolutons and Decisions Annexes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1983. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/159886?show=full (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- WHO. SAFER: A World Free From Alcohol Related Harms; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Seventy-Fifth World Health Assembly—Daily Update: 27 May 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-05-2022-seventy-fifth-world-health-assembly---daily-update--27-may-2022 (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- WHO. Tackling NCD’s: ‘Best Buys’ and Other Recommended Interventions for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Room, R. Alcohol Control and Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1984, 84, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Alcohol Action Plan 2022–2030 to Strengthen Implementation of the Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol: Second draft (Unedited); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-alcohol-action-plan-second-draft-unedited (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Bruun, K.; Edwards, G.; Lumio, M.; Mäkelä, K.; Pan, L.; Popham, R.E.; Room, R.; Schmidt, W.; Skog, O.-J.; Sulkunen, P.; et al. Alcohol Control Policies in Public Health Perspective; The Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies; Rutgers University Center of Alcohol Studies: Helsinki, Finland; New Jersey, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P.; Baumberg, B. Alcohol in Europe: A Public Health Perspective, a Report for the European Commission; Institute of alcohol studies: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 92-79-02241-5. [Google Scholar]

- Babor, T.; Caetano, R.; Casswell, S.; Edwards, G.; Giesbrecht, N.; Graham, K.; Grube, J.; Hill, L.; Holder, H.; Homel, R.; et al. Alcohol: No ordinary commodity, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-19-955114-9. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, G.; Anderson, P.; Babor, T.F.; Casswell, S.; Ferrence, R.; Giesbrecht, N.; Godfrey, C.; Holder, D.H.; Lemmens, P.; Mäkelä, K.; et al. Alcohol Policy and the Public Good; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnardi, V.; Rota, M.; Botteri, E.; Tramacere, I.; Islami, F.; Fedirko, V.; Scotti, L.; Jenab, M.; Turati, F.; Pasquali, E.; et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: A comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rovira, P.; Rehm, J. Estimation of cancers caused by light to moderate alcohol consumption in the European Union. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumgay, H.; Shield, K.; Charvat, H.; Ferrari, P.; Sornpaisarn, B.; Obot, I.; Islami, F.; Lemmens, V.E.P.P.; Rehm, J.; Soerjomataram, I. Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shield, K.; Manthey, J.; Rylett, M.; Probst, C.; Wettlaufer, A.; Parry, C.D.H.; Rehm, J. National, regional, and global burdens of disease from 2000 to 2016 attributable to alcohol use: A comparative risk assessment study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e51–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Making the European Region Safer: Developments in Alcohol Control Policies, 2010–2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Status Report on Alcohol Consumption, Harm and Policy Responses in 30 European Countries 2019. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/411418/Alcohol-consumption-harm-policy-responses-30-European-countries-2019.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- WHO. European Action Plan to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol 2012-2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; ISBN 978 92 890 0286 8. [Google Scholar]

- Angus, C.; Holmes, J.; Meier, P.S. Comparing alcohol taxation throughout the European Union. Addiction 2019, 114, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, P.; O’Donnell, A.; Kaner, E.; Llopis, E.J.; Manthey, J.; Rehm, J. Impact of minimum unit pricing on alcohol purchases in Scotland and Wales: Controlled interrupted time series analyses. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e557–e565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, P. It’s Now against the Law to Sell a Bottle of Wine for under £6.20 in Ireland. Available online: https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2022/01/its-now-against-the-law-to-sell-a-bottle-of-wine-for-under-6-20-in-ireland/ (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- WHO. Alcohol Marketing in the WHO European Region: Update Report on the Evidenve and Recommended Policy Actions. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/alcohol-use/publications/2020/alcohol-marketing-in-the-who-european-region-update-report-on-the-evidence-and-recommended-policy-actions-july-2020 (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- WHO. Alcohol in the European Union: Consumption, Harm and Policy Approaches; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012; ISBN 978 92 890 0264 6. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions Using the Architecture of Choice; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2008; ISBN 9780300122237. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, F.N.; Bitsch, L.; Hanf, J. Nudging—Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der “sanften” Einflussnahme auf den Konsum von Wein in Deutschland. Ber. Über Landwirtsch. 2021, 99, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the Approximation of the Laws, Regulations and Administrative Provisions of the Member States Concerning the Manufacture, Presentation and Sale of Tobacco and Related Products and Repealing Directive 2001/37/EC Text with EEA Relevance: DIRECTIVE 2014/40/EU. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0040 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Schaller, K.; Kahnert, S. Alkoholatlas Deutschland 2017, 1. Auflage; Pabst Science Publishers: Lengerich, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-95853-334-9. [Google Scholar]

- Schaller, K.; Kahnert, S.; Graen, L.; Mons, U.; Ouédraogo, N. Tabakatlas Deutschland 2020, 1. Auflage; Pabst Science Publishers: Lengerich, Germany, 2020; ISBN 978-3-95853-638-8. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl, A. Alkoholpolitik im europäischen Kontext. Rausch Wien. Z. Für Suchttherapie 2015, 4, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl, A. Alkoholpolitik und Verhältnismäßigkeit. Rausch Wien. Z. Für Suchttherapie 2020, 9, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl, A.; Strizek, J. Alkoholprobleme, Alkoholpolitik und wissenschaftliche Fundierung. In 8. Alternativer Drogen- und Suchtbericht 2021, 1. Auflage; Pabst Science Publishers: Lengerich, Germany, 2021; pp. 28–37. ISBN 978-3-95853-717-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kilian, C.; Manthey, J.; Moskalewicz, J.; Sieroslawski, J.; Rehm, J. How Attitudes toward Alcohol Policies Differ across European Countries: Evidence from the Standardized European Alcohol Survey (SEAS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stockwell, T.; Giesbrecht, N.; Vallance, K.; Wettlaufer, A. Government Options to Reduce the Impact of Alcohol on Human Health: Obstacles to Effective Policy Implementation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-J.; Myung, S.-K.; Lee, J.-H. Light Alcohol Drinking and Risk of Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 50, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menotti, A.; Puddu, P.E. How the Seven Countries Study contributed to the definition and development of the Mediterranean diet concept: A 50-year journey. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Pagliai, G.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morze, J.; Danielewicz, A.; Przybyłowicz, K.; Zeng, H.; Hoffmann, G.; Schwingshackl, L. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis on adherence to mediterranean diet and risk of cancer. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 1561–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Lovatt, M.; Eadie, D.; Dobbie, F.; Meier, P.; Holmes, J.; Hastings, G.; MacKintosh, A.M. Public attitudes towards alcohol control policies in Scotland and England: Results from a mixed-methods study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 177, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albors-Llorens, A. The Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 and the Collision between Single-Market Objectives and Public-Interest Requirements. Camb. Law J. 2017, 76, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECJ. C-333/14—The Scotch Whisky Association. Available online: https://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?nat=or&mat=or&pcs=Oor&jur=C%2CT%2CF&num=C-333%252F14 (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Kingreen, T. Vereinbarkeit von Mindestpreisen für alkoholische Getränke mit der Warenverkehrsfreiheit. JURA Jurist. Ausbild. 2016, 38, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, C. Verdrängte Gefahr. Weinwirtschaft 2022, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge, J.; Mialon, M.; Hawkins, B. Alcohol industry involvement in policymaking: A systematic review. Addiction 2018, 113, 1571–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.M. Tobacco and Alcohol Excise Taxes for Improving Public Health and Revenue Outcomes: Marrying Sin and Virtue? Policy Res. Work. Pap. 2015, 7500, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmatenko, L.; Shaverdov, D.K. Gesunde Regulierung? Lebensmittel und Alkohol im Einheitskleid. Z. Für Eur. Int. Priv. Rechtsvgl. 2018, 6, 244–257. [Google Scholar]

- Pabst, E.; Corsi, A.M.; Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A.; Loose, S.M. Consumers’ reactions to nutrition and ingredient labelling for wine—A cross-country discrete choice experiment. Appetite 2021, 156, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, O. Nutri-Score Creator Backs Alcohol Warnings on Label as Italian Wine Sector Brands Any Move ‘an Affront’ to Science. Available online: https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2022/02/09/Nutri-Score-creator-backs-alcohol-warnings-on-label-as-Italian-wine-sector-brands-any-move-an-affront-to-science (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Anderson, P.; Kokole, D. The Impact of Lower-Strength Alcohol Products on Alcohol Purchases by Spanish Households. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Bier—Deutschland. Available online: https://de.statista.com/outlook/cmo/alkoholische-getraenke/bier/deutschland (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Hasenbeck, M. Biermischgetränke auf der Überholspur. Available online: https://blog.drinktec.com/de/bier/biermischgetraenke-auf-der-ueberholspur/#:~:text=Aber%20auch%20der%20Deutsche%20Brauerbund,schon%20bei%20%C3%BCber%20zwanzig%20Prozent (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Smith, C. Coca-Cola Plans to Press on with Alcoholic Beverage ‘Experiments’. Available online: https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2022/08/us-retailers-see-craft-beer-and-hard-seltzer-sales-spike/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Eads, L. The Brands and Trends Shaping the Low- and No-Alcohol Category. Available online: https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2021/03/the-brands-and-trends-shaping-the-low-and-no-alcohol-category/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Zeit Online. Bier, Wein oder Gin: Alkoholfreie Alternativen sind im Trend. Available online: https://www.zeit.de/news/2021-08/05/bier-wein-oder-gin-alkoholfreie-alternativen-sind-im-trend (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Deutsches Weininstitut. Null-Promille Weinalternativen Werden Interessanter. Available online: https://www.deutscheweine.de/presse/pressemeldungen/details/news/detail/News/null-promille-weinalternativen-werden-interessanter/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Keller, E.-M. Das neue Alkoholfrei. Weinwirtschaft 2022, 13, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dempfle, M. Dwv-Stellungnahme Zur, Ersten Verordnung Zur Änderung Der Weinverordnung Und Der Weinüberwachungsverordnung. Available online: https://deutscher-weinbauverband.de/en/dwv-stellungnahme-zur-ersten-verordnung-zur-aenderung-der-weinverordnung-und-der-weinueberwachungsverordnung/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Der Deutsche Weinbau. Anreicherung Oder ENTZUG. Available online: https://www.meininger.de/weinbau/politik-und-verbaende/anreicherung-oder-entzug (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Rüdiger, J.; Hanf, J.H. The use of wine tourism as a possibility of the marketing with wine cooperatives/Die Umsetzung von Weintourismus als Vermarktungsinstrument bei Winzergenossenschaften. In 40th World Congress of Vine and Wine; OIV: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IfD Allensbach. Allensbacher Markt- und Werbeträger-Analyse—AWA; Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach: Allensbach, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wulf, J.-P. Non-Alcoholic is the New Vegan. Available online: https://www.barconvent.com/en-gb/media/News/nuechtern_berlin.html (accessed on 23 August 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schulz, F.N.; Richter, B.; Hanf, J.H. Current Developments in European Alcohol Policy: An Analysis of Possible Impacts on the German Wine Industry. Beverages 2022, 8, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages8040075

Schulz FN, Richter B, Hanf JH. Current Developments in European Alcohol Policy: An Analysis of Possible Impacts on the German Wine Industry. Beverages. 2022; 8(4):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages8040075

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchulz, Frederik Nikolai, Barbara Richter, and Jon H. Hanf. 2022. "Current Developments in European Alcohol Policy: An Analysis of Possible Impacts on the German Wine Industry" Beverages 8, no. 4: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages8040075

APA StyleSchulz, F. N., Richter, B., & Hanf, J. H. (2022). Current Developments in European Alcohol Policy: An Analysis of Possible Impacts on the German Wine Industry. Beverages, 8(4), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages8040075