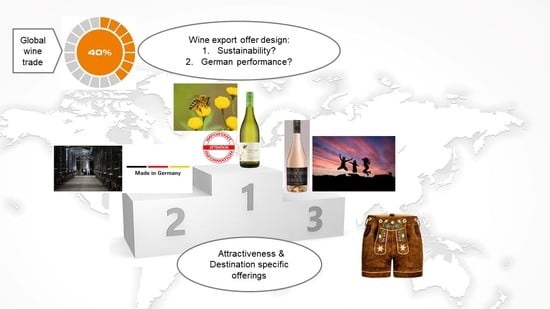

Destination-Centric Wine Exports: Offering Design Concepts and Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. German Wine Export

1.2. Wine Export Management: Key Success Factors and Sustainability

1.3. Exploring Destination-Centric and Sustainable Wine Export Offerings

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Key Offer Components

3.2. Concept of Sustainable Design

3.2.1. Export Concept “Sustainability”

3.2.2. Export Concept “Made in Germany”

3.2.3. Export Concept “Stereotype”

3.2.4. Export Concept “Lifestyle”

3.3. Country Specific Insights

3.3.1. Export Concept for UK

3.3.2. Export Concept for the USA

3.3.3. Export Concept for the Netherlands

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- What business is your company in?

- Importer

- Wholesaler

- Retailer

- Producer

- Monopoly

- Agent

- Other

- In which country is your business located?

- From the following list, please tick the tree most important attributes that describe your sales strategy:

| Price Leadership | Service and Advice |

| Design | Sustainability |

| Tradition | Brands |

| Newcomers | Broad range of countries and origins |

| Special Demand (e.g., “free-of”, special packaging) | Premium/Fine Wine |

- 4.

- How is your share of German wines by turnover? … %

- 5.

- Considering German wines, how would you evaluate your sales strategy? My sales strategy for German wines is mainly:

| Price | Wine Style |

| Entry level | Easy-drinking white |

| Medium price | Easy-drinking red |

| Premium price | Premium dry |

| High-end | Premium sweet |

- 6.

- How would you rate the importance of the following attributes for your wine business in general? (scale 1–5, “very important” bis “not important”)

- Famous brands

- Low price

- Reliable sourcing (i.e., volume provision)

- Support of suppliers in sales activities

- Organic, certified production

- Eco-friendly packaging (e.g., light bottle, Bag in Box)

- Vegan

- Carbon neutral

- Fair Trade

- Sustainable products

- Sustainable producers

- 7.

- How would you rate the performance of the following attributes for German wines? (scale 1–5, “high performance” to “low performance”)

- Famous brands

- Low price

- Reliable sourcing (i.e., volume provision)

- Support of suppliers in sales activities

- Organic, certified production

- Eco-friendly packaging (e.g., light bottle, Bag in Box)

- Vegan

- Carbon neutral

- Fair Trade

- Sustainable products

- Sustainable producers

- 8.

- Do you agree with the following statements about Germany and German wine in general? (scale 1–5 “I totally agree” to “I do not agree at all”)

- German wine has a good taste

- German wine is sustainable

- German wine is innovative

- Germany stands for high quality wine (i.e., technology)

- German wine has a good price

- German wine stands for a modern lifestyle

- German wine stands for tradition

- German wine is a must-have for my business

| Sustainability | Made in Germany | German Clichée | Lifestyle Product | |

| Keywords (for text and design) | Sustainable viticulture, climate protection, biodiversity | “Made in Germany”: Reliability, trust, precision, technology, engineering, cars | Cool climate, Garden gnomes, German “sense of humour” | Modern design No focus on origin, variety, sustainability |

|  |  |  |

- Which packaging would you expect for the concept “sustainability”?

- Normal bottle

- Bottle with reduced weight

- Bag-in-Box (BiB)

- Which sales channels would you evaluate most suitable for the concept “sustainability”?

- Which price level would you evaluate most suitable for the concept “sustainability”?

- Entry level

- Medium level

- Premium level

- High-end

- What kind of wine style would you associate most with the concept “sustainability”?

- “Free-of”: Reduced alcohol and calories, fruity, semi-dry

- Light-bodied: Crisp and fruity, easy-drinking, low-to-medium alcohol, off-dry

- Medium-bodied: Rich with medium alcohol, ripe flavours, dry, lightly oaked, to serve with food

- Natural style: e.g., Orange or Natural wine, Pet Nat, reduced sulfur

- Sparkling: Prosecco-like wine style

- How would you rate the importance to mention the following terms on the label for the concept “sustainability” (scale 1–5, “very important” to “not important”):

- Wine growing region (e.g., Pfalz, Baden, Rheinhessen)

- Grape variety (e.g., Cabernet Blanc, Muscaris or Souvignier Gris)

- Organic production

- How would you evaluate the chance that a German wine with the concept “sustainability” will be included in your range? (1 = very unlikely to 10 = very likely)

References

- Dana, L.-P.; Grandinetti, R.; Mason, M.C. International entrepreneurship, export planning and export performance: Evidence from a sample of winemaking SMEs. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2016, 29, 602–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaum, G.; Duerr, E.; Josiassen, A. International Marketing and Export Management; Pearson Education: Harlow, England, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, F.J.; Parejo-Moruno, F.M.; Rangel-Preciado, J.F.; Cruz-Hidalgo, E. Regulation of agricultural trade and its implications in the reform of the CAP. The continental products case study. Agriculture 2021, 11, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausmann, F.; Langthaler, E. Food regimes and their trade links: A socio-ecological perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 160, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, P. State of the vitivinicultural world in 2022. In Proceedings of the OIV Press Conference, Dijon, France, 20 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. State of the vitivinicultural world in 2020. In Proceedings of the OIV Press Conference, Paris, France, 4 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rückrich, K. Daten zur Weltweinwirtschaft. Der Deutsche Weinbau 2017, 10, 12. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. World Vitiviniculture Situation 2016; OIV: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- COGEA. Study on the Competitiveness of European Wines; European Union: Luxemburg, 2014; pp. 1–146. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. World Vitiviniculture Situation 2013; OIV: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Charters, S.; Menival, D. The impact of the geographical reputation on the value created by small producers in Champagne. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 8–10 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Seguin, G. The concept of terroir in viticulture. J. Wine Res. 2006, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinitrac, Building Successful Wine Brands; Wine-Market Research Reports: Mainz, Germany, November 2016.

- Mathäß, J. Globalisierung im Glas. Rheinpfalz Am. Sonntag 2018, 9, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Trick, S. Der Deutsche Wein und Die Globalisierung; Europäischer Hochschulverlag: Bremen, Germany, 2009; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Kump, B.; Schweiger, C. Mere adaptability or dynamic capabilities? A qualitative multi-case study on how SMEs renew their resource bases. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2022, 14, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejardin, M.; Raposo, M.L.; Ferreira, J.J.; Fernandes, C.I.; Veiga, P.M.; Farinha, L. The impact of dynamic capabilities on SME performance during COVID-19. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 17, 1703–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey. Bedeutung strategischer Planung im Krisenmodus. In Proceedings of the ZIRP Erfolgsfaktor Unternehm, Online Presentation, 1 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Goumagias, N.; Fernandes, K.; Cabras, I.; Li, F.; Shao, J.; Devlin, S.M.; Hodge, V.J.; Cowling, P.I.; Kudenko, D. A Conceptual Framework of Business Model Emerging Resilience. In Proceedings of the 32nd European Group for Organization Studies (EGOS) Colloquium, Naples, Italy, 7–9 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, C.R.; da Silva, A.L.; Tate, W.L.; Christopher, M. Purchasing and supply management (PSM) contribution to supply-side resilience. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 228, 107740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom, D.; Arregle, J.L.; Hitt, M.A.; Qian, G.; Ma, X.; Faems, D. Managing technological, sociopolitical, and institutional change in the new normal. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinke, O. Weizenpreise Steigen. Available online: https://www.agrarheute.com/markt/marktfruechte/getreidepreise-kriegsgefahr-ukraine-treibt-weizenpreise-590292 (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Arifin, B. On the competitiveness and sustainability of the Indonesian agricultural export commodities. ASEAN J. Econ. Manag. Account. 2013, 1, 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.L.; Zhou, L.; Wu, A. The supply-side of environmental sustainability and export performance: The role of knowledge integration and international buyer involvement. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; De, P. Environmental sustainability practices and exports: The interplay of strategy and institutions in Latin America. J. World Bus. 2020, 55, 101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, G.; Selvaggi, R.; Pecorino, B.; Lee, J.Y.; Nayga, R.M. Assessing experiential augmentation of the environment in the valuation of wine: Evidence from an economic experiment in Mt. Etna, Italy. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storchmann, K. Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Wine Glob. A New Comp. Hist. 2018, 2, 92. [Google Scholar]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2022/2023; DWI: Mainz, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tegtmeier, S.; Meyer, V. Experts of thoroughness and fanatics of planning? Daring insights into the decision-making of German entrepreneurs. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2018, 33, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M. Managing export success–An empirical picture of German wineries’ performance. In Proceedings of the BIO Web of Conferences, OIV Conference, Mainz, Germany, 1 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs, H.; Laws, N. “Sustainability state” in the making? Institutionalization of sustainability in German federal policy making. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2623–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergmann, A.; Posch, P. Mandatory sustainability reporting in Germany: Does size matter? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Red. Weinmarkt Stark Rückläufig. Available online: https://www.meininger.de/wein/handel/weinmarkt-stark-ruecklaeufig (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Gladwin, T.N.; Kennelly, J.J.; Krause, T.-S. Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: Implications for management theory and research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 874–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Jacobides, M.G.; Cennamo, C.; Gawer, A. Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 2255–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sala, S.; Ciuffo, B.; Nijkamp, P. A systemic framework for sustainability assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westley, F.R.; Tjornbo, O.; Schultz, L.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Crona, B.; Bodin, Ö. A theory of transformative agency in linked social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsato, R.J. Competitive environmental strategies: When does it pay to be green? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paehlke, R. Sustainability as a bridging concept. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esty, D.C.; Porter, M.E. Industrial ecology and competitiveness: Strategic implications for the firm. J. Ind. Ecol. 1998, 2, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgerson, D. The uncertain quest for sustainability: Public discourse and the politics of environmentalism. In Greening Environmental Policy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Golicic, S.L. Changes in sustainability in the global wine industry. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2022, 34, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cortijo, M.C.; Ferrer, J.R.; Castillo-Valero, J.S.; Pinilla, V. The Drivers of the Sustainability of Spanish Wineries: Resources and Capabilities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouvrard, S.; Jasimuddin, S.M.; Spiga, A. Does sustainability push to reshape business models? Evidence from the European wine industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamann, R.; Smith, J.; Tashman, P.; Marshall, R.S. Why do SMEs go green? An analysis of wine firms in South Africa. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, E.; Migliore, G.; Di Franco, C.P.; Borsellino, V. Is there sustainable entrepreneurship in the wine industry? Exploring Sicilian wineries participating in the SOStain program. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilinsky, A.; Newton, S.K.; Vega, R.F. Sustainability in the global wine industry: Concepts and cases. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R.; Mariani, A. Wineries’ perception of sustainability costs and benefits: An exploratory study in California. Sustainability 2015, 7, 16164–16174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forbes, S.L.; Cullen, R.; Grout, R. Adoption of environmental innovations: Analysis from the Waipara wine industry. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dodds, R.; Graci, S.; Ko, S.; Walker, L. What drives environmental sustainability in the New Zealand wine industry? An examination of driving factors and practices. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2013, 25, 164–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, T.; Gilinsky, A.; Newton, S.K. Sustainability in the Wine Industry: Altering the Competitive Landscape? In Proceedings of the AWBR International Conference, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stranieri, S.; Varacca, A.; Casati, M.; Capri, E.; Soregaroli, C. Adopting environmentally-friendly certifications: Transaction cost and capabilities perspectives within the Italian wine supply chain. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 27, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2010/2011; Deutsches Weininstitut: Mainz, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2015/2016; Deutsches Weininstitut: Mainz, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2019/2020; Deutsches Weininstitut: Mainz, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2021/2022; Deutsches Weininstitut: Mainz, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2020/2021; Deutsches Weininstitut: Mainz, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Deckers, D. The Sign of the Grape and Eagle: A History of German Wine; Frankfurt Academic Press: Frankfurt, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, K.D. German Wine and the Fermentation of Modern Taste, 1850–1914; University of California, Los Angeles: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K.; Nelgen, S. Global Wine Markets 1961–2009: A Statistical Compendium; University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. World Statistics; OIV: Porto, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schallenberger, F. Weinbau. Made in Germany. Der deutsche Weinmarkt im Blickfeld; LBBW: Mainz, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- DWI. Weinmarkt 2010; DWI: Mainz, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ddw. Deutliche Kaufzurückhaltung. Meining. De 2023, 27, 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. World Vitiviniculture Situation 2012; OIV: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, S.; Beciu, S.; Karbauskas, A. Globalising chains—Decoupling grape production, wine production and wine exports. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.M. Export performance measurement: An evaluation of the empirical research in the literature. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2004, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Julien, P.-A.; Ramangalahy, C. Competitive strategy and performance of exporting SMEs: An empirical investigation of the impact of ther export information seach and competencies. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 27, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramon-Jeronimo, J.M.; Florez-Lopez, R.; Araujo-Pinzon, P. Resource-based view and SMEs performance exporting through foreign intermediaries: The mediating effect of management controls. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gemünden, H.G. Success factors of export marketing. In Perspectives on International Marketing-Re-Issued (RLE International Business); Paliwoda, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; Volume 29, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddoha, A.K.; Ali, M.Y. Mediated effects of export promotion programs on firm export performance. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2006, 18, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodlaj, M.; Kadic-Maglajlic, S.; Vida, I. Disentangling the impact of different innovation types, financial constraints and geographic diversification on SMEs‘ export growth. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 108, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, A.M.; Lockshin, L.; Mueller, S. Competition between and competition within: The strategic positioning of competing countries in key export markets. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of the Academy of Wine Business Research, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, I.M.; Eroglu, S. Measuring a multi-dimensional construct: Country image. J. Bus. Res. 1993, 28, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Climate Sentiment—Klimasorgen Beeinflussen das Verbraucherverhalten in Deutschland; Deloitte Consulting: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, L.; Ortega, R.; Moscovici, D.; Gow, J.; Alonso Ugaglia, A.; Mihailescu, R. Consumer Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Wine—The Chilean Case. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GfK. Kinder Beeinflussen Nachhaltigen Konsum; GfK: Nuremberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper, D. The Roots of Modern Environmentalism; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Handelsblatt. Nachhaltigkeit Wird Kunden Immer Wichtiger. Available online: https://www.handelsblatt.com/adv/hearconomy/zukunfthandel/zukunft-des-handels-nachhaltig-erfolgreich-wie-der-einzelhandel-gruener-wird-/26652596.html (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- HDE. Nachhaltigkeit im Handel: Der Einzelhandel übernimmt Verantwortung; Handelsverband Deutschland: Berlin, Germany, 2017; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Pitelis, C.N.; Teece, D.J. Cross-border market co-creation, dynamic capabilities and the entrepreneuria theory of the multinational enterprise. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2010, 19, 1247–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benson-Rea, M.; Woodfield, P.; Brodie, R.J.; Lewis, N. Sustainability in Strategy: Maintaining a Premium Position for New Zealand Wine. In Proceedings of the 6th AWBR International Conference, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, D.J.; Golicic, S.L.; Signori, P. Sustainability through resilience: The Very Essence of the Wine Industry. In Proceedings of the 6th AWBR International Conference, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gbejewoh, O.; Keesstra, S.; Blancquaert, E. The 3ps (Profit, planet, and people) of sustainability amidst climate change: A south african grape and wine perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.S.; Cordano, M.; Silverman, M. Exploring individual and institutional drivers of proactive environmentalism in the US wine industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2005, 14, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, F.; Testa, R.; Tudisca, S.; Trapani, A.M.D.; Dana, L.-P. Growth and sustainability of agricultural systems: The case of Sicilian wine-growing farms. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2016, 29, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.; Taylor, C.; Strick, S. Wine consumers‘ environmental knowledge and attitudes: Influence on willingness to purchase. Int. J. Wine Res. 2009, 1, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Casini, L.; Cavicchi, A.; Corsi, A.; Santini, C. Hopelessly devoted to sustainability: Marketing challenges to face in the wine business. In Proceedings of the 119th EAAE Seminar ‘Sustainability in the Food Sector: Rethinking the Relationship between the Agro-Food System and the Natural, Social, Economic and Institutional Environments, Capri, Italy, 30 June–2 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, M.L. Rethinking new wines: Implications of local and environmentally friendly labels. Food Policy 2003, 28, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, L.I.; Washburn, J.H. Building Brand Equity: Consumer Reactions to Proactive Environmental Policies by the Winery. Int. J. Wine Mark. 2002, 14, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. Reaching for Customer Centricity—Wine Brand Positioning Configurations. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, C.; Schwab, J.; Berger, A.; Morin, J.-F. Do environmental provisions in trade agreements make exports from developing countries greener? World Dev. 2020, 129, 104899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, M.A.; Van Asselt, H.; Das, K.; Droege, S.; Verkuijl, C. Designing border carbon adjustments for enhanced climate action. Am. J. Int. Law 2019, 113, 433–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awan, U.; Nauman, S.; Sroufe, R. Exploring the effect of buyer engagement on green product innovation: Empirical evidence from manufacturers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Alvarado, R.; Murshed, M.; Tillaguango, B.; Toledo, E.; Méndez, P.; Isik, C. Effect of agricultural employment and export diversification index on environmental pollution: Building the agenda towards sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, I.; Castillo-Valero, J.S.; Córcoles, C.; Carchano, M. Greening Wine Exports? Changes in the Carbon Footprint of Spanish Wine Exports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Casini, L. Sustainability in the wine industry: Key questions and research trends a. Agric. Food Econ. 2013, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, J.; Liu, L. Profiting from green innovation: The moderating effect of competitive strategy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bouzdine-Chameeva, T.; Krzywoszynska, A. Barriers and Driving Forces in Organic Winemaking in Europe. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of the Association of Wine Business Research, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- DWI. Öko-Weinbau in Deutschland Immer Beliebter. 2018. Available online: https://www.deutscheweine.de/wissen/weinbau-weinbereitung/oekologischer-anbau/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Krämer, L. Planning for climate and the environment: The EU green deal. J. Eur. Environ. Plan. Law 2020, 17, 267–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanarella, L.; Panagos, P. The relevance of sustainable soil management within the European Green Deal. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, S.S. What is sustainability in the wine world? A cross-country analysis of wine sustainability frameworks. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 2301–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurel, C.; Ugaglia, A.A.; Del‘Homme, B. Evolution of the concept of performance in the wine industry: A literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2017, 32, 254–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsei, M.; Polyakovskiy, S. Sustainable supply chain network design: A case of the wine industry in Australia. Omega 2017, 66, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, R.; Freeman, R.E.; Hockerts, K. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability in Scandinavia: An overview. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, L.; Adebayo, T.S.; Yue, X.-G.; Umut, A. The role of renewable energy consumption and financial development in environmental sustainability: Implications for the Nordic Countries. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2023, 30, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillis, A.; Grigoroudis, E.; Kouikoglou, V.S. Assessing national energy sustainability using multiple criteria decision analysis. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2021, 28, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P. Sustainable Sourcing of Nordic Wine Importers: The Role of Drivers and Barriers; University of Vaasa: Vaasa, Finland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Agency, E.F. Organic Wine: Italy is Strong in Sweden. EFA News. Available online: https://www.efanews.eu/item/31297-organic-wine-italy-is-strong-in-sweden-42-of-the-market (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- D`Aveni, R. Hypercompetition: The Dynamics of Strategic Maneuvering; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, J.-A.; Olaisen, J.; Olsen, B. Managing and organizing innovation in the knowledge economy. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 1999, 2, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtström, J. Business model innovation under strategic transformation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 34, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, F.; Souto-Pérez, J.E. Sustainability, innovative orientation and export performance of manufacturing SMEs: An empirical analysis of the mediating role of corporate image. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2016, 9, 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Maurel, C. Determinants of export performance in French wine SMEs. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 118–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Reinventing marketing to manage the environmental imperative. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing; Pearson Education: Ahmedabad, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management; Prentice-Hall: Harlow, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V. Managing Customers for Profit: Strategies to Increase Profits and Build Loyalty; Prentice Hall Professional: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaout, B.; Esposito, M. The value of communication in turbulent environments: How SMEs manage change successfully in unstable surroundings. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2018, 34, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Service Management and Marketing; John Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2015; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Vivek, S.D.B.; Sharon, E.; Morgan, R.M. Customer Engagement: Exploring Customer Relationships Beyond Purchase. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2012, 20, 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleka, A. Resources and capabilities driving competitive advantage in export markets: Guidelines for industrial exporters. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2002, 31, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeh, J.N.; Obodoechi, D.N.; Ramos-Hidalgo, E. Effects of innovation strategies on export performance: New empirical evidence from developing market firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 158, 120167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahat, M.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Ramayah, T. Analysing the importance of international knowledge, orientation, networking and commitment as entrepreneurial culture and market orientation in gaining competitive advantage and international performance. Int. Mark. Rev. 2022, 39, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertragslage Garten-und Weinbau 2020; Bundesministerium fur Ernahrung und Landwirtschaft: Bonn, Germany, 2021.

- Ertragslage Garten-und Weinbau 2019; Bundesministerium fur Ernahrung und Landwirtschaft: Bonn, Germany, 2020.

- Loose, S.; Pabst, E. Current State of the German and International Wine Markets. Oceania 2018, 67, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, L.; Skvortsova, V.; Kullen, C.; Weber, B.; Plassmann, H. How context alters value: The brain’s valuation and affective regulation system link price cues to experienced taste pleasantness. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnabel, H.; Storchmann, K. Prices as quality signals: Evidence from the wine market. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2010, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockshin, L.; Jarvis, W.; d’Hauteville, F.; Perrouty, J.-P. Using simulations from discrete choice experiments to measure consumer sensitivity to brand, region, price, and awards in wine choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Mohsin, M. The power of emotional value: Exploring the effects of values on green product consumer choice behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, H. Environmental concern and the adoption of organic agriculture. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Agriculture and the food industry in the information age. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2005, 32, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkerbout, M.; Egenhofer, C.; Núñez Ferrer, J.; Catuti, M.; Kustova, I.; Rizos, V. The European Green Deal after Corona: Implications for EU climate policy. CEPS Policy Insights 2020, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bartunek, J.M.; Rynes, S.L.; Ireland, R.D. What makes management research interesting, and why does it matter? Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Suddaby, R. From the editors: What grounded theory is not. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossey, E.; Harvey, C.; McDermott, F.; Davidson, L. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2002, 36, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.P.; Dana, T.E. Expanding the scope of methodologies used in entrepreneurship research. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2005, 2, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boone, H.N.; Boone, D.A. Analyzing likert data. J. Ext. 2012, 50, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cool, K.; Dierickx, I. Rivalry, strategic groups, and performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 16, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruso, L.C.; Weinzimmer, L.G. A normative framework to assess small-firm entry strategies: A resource-based view. J. Small Bus. Strategy 1999, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Neely, A.; Hii, J. Innovation and business performance: A literature review. Judge Inst. Manag. Stud. Univ. Camb. 1998, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Duley, G.; Ceci, A.T.; Longo, E.; Boselli, E. Oenological potential of wines produced from disease-resistant grape cultivars. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaigne, E.; Coelho, A.; Zadmehran, S. A comprehensive economic examination and prospects on innovation in new grapevine varieties dealing with global warming and fungal diseases. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova-Gascón, J.; Ferrer-Martín, C.; Bernad-Eustaquio, A.; Elbaile-Mur, A.; Ayuso-Rodríguez, J.M.; Torres-Sánchez, S.; Jarne-Casasús, A.; Martín-Ramos, P. Behavior of vine varieties resistant to fungal diseases in the Somontano region. Agronomy 2019, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vecchio, R.; Pomarici, E.; Giampietri, E.; Borrello, M. Consumer acceptance of fungus-resistant grape wines: Evidence from Italy, the UK, and the USA. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267198. [Google Scholar]

- Borrello, M.; Cembalo, L.; Vecchio, R. Consumers’ acceptance of fungus resistant grapes: Future scenarios in sustainable winemaking. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 307, 127318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, K.; Legrand, W.; Sloan, P. The integration of fungus tolerant vine cultivars in the organic wine industry: The case of German wine producers. Enometrica 2010, 2, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Montaigne, E.; Coelho, A.; Khefifi, L. Economic issues and perspectives on innovation in new resistant grapevine varieties in France. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommission, E. Evolution of PPP on Specialty Crops in the EU 15. 2008. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-statistical-books/-/KS-76-06-669 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Wine Intelligence. Global SOLA: Opportunities for Sustainbale and Organic Wine; Deutsches Weininstitut: Mainz, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pucci, T.; Casprini, E.; Nosi, C.; Zanni, L. Does social media usage affect online purchasing intention for wine? The moderating role of subjective and objective knowledge. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoldy, S.; Wulff, C. Surviving the Retail Apocalypse; Price Waterhouse Coopers: Frankfurt, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, F.; Rau, C.; Gassmann, O.; van den Hende, E. Technologically Reflective Individuals as Enablers of Social Innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garofano, A.R.A. A Shared History for a Shared Project: Using Storytelling and Collaborative Relationships to Launch a New Product. In Proceedings of the 7th AWBR International Conference, St. Catharines, ON, Canada, 12–15 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Woodside, A.G. Brand-consumer storytelling theory and research: Introduction to a Psychology & Marketing special issue. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 531–540. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Feinberg, R.A. The LOHAS (lifestyle of health and sustainability) scale development and validation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmke, S.; Scherberich, J.-U.; Uebel, M. LOHAS-Marketing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pomarici, E.; Sardone, R. EU wine policy in the framework of the CAP: Post-2020 challenges. Agric. Food Econ. 2020, 8, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wine Intelligence. Wine Trends UK; Deutsches Weininstitut: Mainz, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, R. Younger US Consumers Turn to Red Wine—And Non-Alc. Meiningers Wine Business International. Available online: www.meiningers-international.com/wine/red-wine (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Wine Intelligence. United States Wine Landscapes 2022; Deutsches Weininstitut: Mainz, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wine Intelligence. Netherlands Returns to the New Normal; Deutsches Weininstitut: Mainz, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Rai, B.K.; Griffin, M. Resilience and competitiveness of small and medium size enterprises: An empirical research. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5489–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Nonino, F. Strategic and operational management of organizational resilience: Current state of research and future directions. Omega 2016, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, G.J. Systemische Resilienz—Die Perspektiven und das Resilienz-Quadarat. Organ. Superv. Coach. 2016, 23, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crals, E.; Vereeck, L. The affordability of sustainable entrepreneurship certification for SMEs. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2005, 12, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, S.A.S.; Robert, P.; Calantone, R. Assessing the impact of environmental management systems on corporate and environmental performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croitoru, G.; Duica, M.; Robescu, O.; Valentin, R.; Oprisan, O. Entrepreneurial Resilience, Factor of Influence on the Function of Entrepreneur. Risk Contemp. Econ. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, E. Does environmental management improve financial performance? A meta-analytical review. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Gilinsky, A.; Newton, S.; Rabino, S. Niche Strategy and Resources: Dilemmas and Open Questions, an Exploratory Study. In Proceedings of the Academy of Wine Business Research, 8th International Conference, Geisenheim, Germany, 28–30 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetti, S.; Ogliastri, E.; Caputo, A. Distributive/integrative negotiation strategies in cross-cultural contexts: A comparative study of the USA and Italy. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 27, 786–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. The Organizational Culture Project 2019. Available online: https://geerthofstede.com/research-and-vsm (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Lin, H.-E.; McDonough, E.F.; Yang, J.; Wang, C. Aligning Knowledge Assets for Exploitation, Exploration, and Ambidexterity: A Study of Companies in High-Tech Parks in China. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 34, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, S. Open, networked and dynamic innovation in the food and beverage industry. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2290–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challita, S.; Aurier, P.; Sentis, P. Linking Branding Strategy to Ownership Structure and Financial Performance and Stability: Case of French Wine Cooperatives. In Marketing at the Confluence between Entertainment and Analytics; Rossi, P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 745–757. [Google Scholar]

- Eling, K.; Herstatt, C. Managing the Front End of Innovation-Less Fuzzy, Yet Still Not Fully Understood. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 34, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadieu, P.; Maurel, C.; Viviani, J.-L. Intangible Expenses, Export Intensity and Company Performance in the French Wine Industry. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Maurel, C. Determinants of Export Performance in SMEs: The Case of the French Wine Industry. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 118–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S.T.; Hult, G.T.M.; Kiyak, T.; Deligonul, S.; Lagerström, K. What Drives Performance in Globally Focused Marketing Organizations? A Three-Country Study. J. Int. Mark. 2007, 15, 58–85. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Santos, F.M. Knowledge-based view: A new theory of strategy. Handb. Strategy Manag. 2002, 1, 139–164. [Google Scholar]

| Concept Title | Sustainability | Made in Germany | Stereotypes | Lifestyle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concept idea | Pointing out the sustainability (benefits regarding resource efficient viticulture, biodiversity, saving emissions …) with strong emphasis on FRG. | Germany is internationally perceived for technology, innovation, and precision (machinery industry; cars): Newly bred varieties are a result of long-term research and engineering “made in Germany”. | Germans are punctual, wear traditional clothes, and party (Oktoberfest). Playful usage of stereotypes likewise “the arrogant frog” | Wine drinkers want to enjoy it! No matter about origin, variety, or wine production. Wine enlightens easy living (e.g., a picnic, BBQ, cooking with friends or just having fun) |

| Key words | Sustainable viticulture, climate protection, eco-friendly, biodiversity, nature | Reliability, trust, precision, engineering, grapevine breeding | Lederhosen (leather trousers), tradition and customs, “German humor”, Cool Climate | urban, fun, lifestyle, freedom, trendy, easy-drinking |

| Concept Title | Sustainability | Made in Germany | Stereotypes | Lifestyle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractiveness/Probability of purchase (1–7) | 5.8 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 4.7 |

| Packaging | ||||

| Light bottle | 63% | 53% | 15% | 50% |

| Bag-in-Box (BiB) | 11% | 4% | 13% | 22% |

| Price level | ||||

| Entry | 14% | 10% | 48% | 38% |

| Medium | 68% | 57% | 39% | 53% |

| Premium | 44% | 52% | 26% | 25% |

| Super premium | 15% | 15% | 6% | 5% |

| Wine style expectations | ||||

| Low alcohol, fruity … | 16% | 10% | 13% | 36% |

| Complex and rich | 34% | 43% | 30% | 21% |

| Nature style (e.g., Orange, PetNat) | 41% | 19% | 10% | 25% |

| Sparkling … | 8% | 12% | 10% | 36% |

| Relevance of … (1–5) | ||||

| Region/origin | 3.5 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 2.8 |

| Varietal | 3.3 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 3.0 |

| Organic certification | 4.2 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 3.4 |

| Certified sustainable | 4.3 | ./. | ./. | ./. |

| Concept | Overall | UK | NL | USA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| Made in Germany | 5.4 | 4.6 | 5.9 | 4.9 |

| Stereotyp | 3.8 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 |

| Lifestyle | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dressler, M. Destination-Centric Wine Exports: Offering Design Concepts and Sustainability. Beverages 2023, 9, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9030055

Dressler M. Destination-Centric Wine Exports: Offering Design Concepts and Sustainability. Beverages. 2023; 9(3):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9030055

Chicago/Turabian StyleDressler, Marc. 2023. "Destination-Centric Wine Exports: Offering Design Concepts and Sustainability" Beverages 9, no. 3: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9030055

APA StyleDressler, M. (2023). Destination-Centric Wine Exports: Offering Design Concepts and Sustainability. Beverages, 9(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9030055