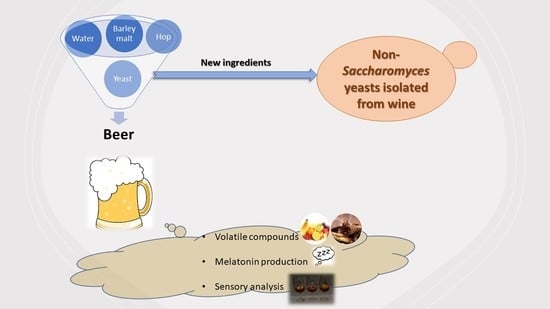

New Approaches for the Fermentation of Beer: Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Wine

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Collection

2.2. Preliminary Screening

- Type I (white/creme): low-null production H2S

- Type II (light brown): moderate production H2S

- Type III (brown): high production H2S

- Type IV (dark brown/black): very high production H2S

2.3. Laboratory Scale Fermentations: 100 mL and 1 L

2.4. Beer Analysis

2.5. Determination of Major Aromatic Compounds

2.6. Determination of Melatonin

2.7. Sensory Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preliminary Screening of Non-Saccharomyces Strains

3.2. Beer Analysis

3.3. Aromatic Profiles in 100 mL Fermentations

3.4. Melatonin Production

3.5. Statistical Analysis

3.6. Fermentation Kinetics in 1 L

3.7. Sensory Analysis of Beers

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jolly, N.P.; Varela, C.; Pretorius, I.S. Not Your Ordinary Yeast: Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts in Wine Production Uncovered. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014, 14, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Varela, C. The Impact of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts in the Production of Alcoholic Beverages. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 9861–9874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderhaegen, B.; Neven, H.; Coghe, S.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Derdelinckx, G.; Verachtert, H. Bioflavoring and Beer Refermentation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 62, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorizzo, M.; Coppola, F.; Letizia, F.; Testa, B.; Sorrentino, E. Role of Yeasts in the Brewing Process: Tradition and Innovation. Processes 2021, 9, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capece, A.; Romaniello, R.; Siesto, G.; Romano, P. Conventional and Non-Conventional Yeasts in Beer Production. Fermentation 2018, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basso, R.F.; Alcarde, A.R.; Portugal, C.B. Could Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts Contribute on Innovative Brewing Fermentations? Food Res. Int. 2016, 86, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero, A.; Quintilla, R.; Groenewald, M.; Alkema, W.; Boekhout, T.; Hazelwood, L. High-Throughput Screening of a Large Collection of Non-Conventional Yeasts Reveals Their Potential for Aroma Formation in Food Fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2016, 60, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.; Mukherjee, V.; Lievens, B.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Thevelein, J.M. Bioflavoring by Non-Conventional Yeasts in Sequential Beer Fermentations. Food Microbiol. 2018, 72, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura-Nunes, N.; Brito, T.C.; Da Fonseca, N.D.; De Aguiar, P.F.; Monteiro, M.; Perrone, D.; Torres, A.G. Phenolic Compounds of Brazilian Beers from Different Types and Styles and Application of Chemometrics for Modeling Antioxidant Capacity. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michel, M.; Kopecká, J.; Meier-Dörnberg, T.; Zarnkow, M.; Jacob, F.; Hutzler, M. Screening for New Brewing Yeasts in the Non-Saccharomyces Sector with Torulaspora delbrueckii as Model. Yeast 2016, 33, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Canonico, L.; Agarbati, A.; Comitini, F.; Ciani, M. Torulaspora delbrueckii in the Brewing Process: A New Approach to Enhance Bioflavour and to Reduce Ethanol Content. Food Microbiol. 2016, 56, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domizio, P.; House, J.F.; Joseph, C.M.L.; Bisson, L.F.; Bamforth, C.W. Lachancea thermotolerans as an Alternative Yeast for the Production of Beer. J. Inst. Brew. 2016, 122, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brányik, T.; Silva, D.P.; Baszczyňski, M.; Lehnert, R.; Almeida E Silva, J.B. A Review of Methods of Low Alcohol and Alcohol-Free Beer Production. J. Food Eng. 2012, 108, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochlánová, T.; Kij, D.; Kopecká, J.; Kubizniaková, P.; Matoulková, D. Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts and Their Importance in the Brewing Industry. Part II. Kvas. Prum. 2016, 62, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johansson, L.; Nikulin, J.; Juvonen, R.; Krogerus, K.; Magalhães, F.; Mikkelson, A.; Nuppunen-Puputti, M.; Sohlberg, E.; de Francesco, G.; Perretti, G.; et al. Sourdough Cultures as Reservoirs of Maltose-Negative Yeasts for Low-Alcohol Beer Brewing. Food Microbiol. 2021, 94, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravasio, D.; Carlin, S.; Boekhout, T.; Groenewald, M.; Vrhovsek, U.; Walther, A.; Wendland, J. Adding Flavor to Beverages with Non-Conventional Yeasts. Fermentation 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maldonado, M.D.; Moreno, H.; Calvo, J.R. Melatonin Present in Beer Contributes to Increase the Levels of Melatonin and Antioxidant Capacity of the Human Serum. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 28, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, D.; Branco, G.F.; Faria, J.D.A.F.; Cruz, A.G. Characterization of Brazilian Lager and Brown Ale Beers Based on Color, Phenolic Compounds, and Antioxidant Activity Using Chemometrics. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.-X.; Maldonado, M.D. Melatonin as an Antioxidant: Physiology versus Pharmacology. J. Pineal Res. 2005, 39, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, M.D.; Manfredi, M.; Ribas-Serna, J.; Garcia-Moreno, H.; Calvo, J.R. Melatonin Administrated Immediately before an Intense Exercise Reverses Oxidative Stress, Improves Immunological Defenses and Lipid Metabolism in Football Players. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 105, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeggeler, B.; Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.-X.; Chen, L.; Manchester, L.C. Melatonin, Hydroxyl Radical-Mediated Oxidative Damage, and Aging: A Hypothesis. J. Pineal Res. 1993, 14, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Hidalgo, M.; de la Lastra, C.A.; Carrascosa-Salmoral, M.P.; Naranjo, M.C.; Gomez-Corvera, A.; Caballero, B.; Guerrero, J.M. Age-Related Changes in Melatonin Synthesis in Rat Extrapineal Tissues. Exp. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maldonado, M.D.; Mora-Santos, M.; Naji, L.; Carrascosa-Salmoral, M.P.; Naranjo, M.C.; Calvo, J.R. Evidence of Melatonin Synthesis and Release by Mast Cells. Possible Modulatory Role on Inflammation. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 62, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motilva, V.; García-Mauriño, S.; Talero, E.; Illanes, M. New Paradigms in Chronic Intestinal Inflammation and Colon Cancer: Role of Melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 51, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Kim, S.J.; Youn, J.-P.; Hwang, S.Y.; Park, C.-S.; Park, Y.S. MicroRNA and Gene Expression Analysis of Melatonin-Exposed Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines Indicating Involvement of the Anticancer Effect. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 51, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Barcelo, E.J.; Mediavilla, M.D.; Alonso-Gonzalez, C.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin Uses in Oncology: Breast Cancer Prevention and Reduction of the Side Effects of Chemotherapy and Radiation. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2012, 21, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, M.D.; Siu, A.W.; Sánchez-Hidalgo, M.; Acuna-Castroviejo, D.; Escames, G. Melatonin and Lipid Uptake by Murine Fibroblasts: Clinical Implications. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2006, 27, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koziróg, M.; Poliwczak, A.R.; Duchnowicz, P.; Koter-Michalak, M.; Sikora, J.; Broncel, M. Melatonin Treatment Improves Blood Pressure, Lipid Profile, and Parameters of Oxidative Stress in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 50, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morera, A.L.; Abreu, P. Seasonality of Psychopathology and Circannual Melatonin Rhythm. J. Pineal Res. 2006, 41, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordero-Bueso, G.; Esteve-Zarzoso, B.; Cabellos, J.M.; Gil-Díaz, M.; Arroyo, T. Biotechnological Potential of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts Isolated during Spontaneous Fermentations of Malvar (Vitis vinifera cv. L.). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 236, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzman, C.P.; Fell, J.W.; Boekhout, T.; Robert, V. Methods for Isolation, Phenotypic Characterization and Maintenance of Yeasts; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 1, ISBN 9780444521491. [Google Scholar]

- Capece, A.; Romaniello, R.; Pietrafesa, A.; Siesto, G.; Pietrafesa, R.; Zambuto, M.; Romano, P. Use of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Var. boulardii in Co-Fermentations with S. cerevisiae for the Production of Craft Beers with Potential Healthy Value-Added. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 284, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.C.; Ingledew, W.M. Fuel Alcohol Production: Effects of Free Amino Nitrogen on Fermentation of Very-High-Gravity Wheat Mashes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990, 56, 2046–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- CDR FoodLab. Quality Control Systems for Food and Beverage. Available online: https://www.cdrfoodlab.com/ (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Campden BRI Food and Drink Innovation. Available online: https://www.campdenbri.co.uk/ (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Ortega, C.; López, R.; Cacho, J.; Ferreira, V. Fast Analysis of Important Wine Volatile Compounds—Development and Validation of a New Method Based on Gas Chromatographic-Flame Ionisation Detection Analysis of Dichloromethane Microextracts. J. Chromatogr. A 2001, 923, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Naranjo, M.I.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Troncoso, A.M.; Cantos-Villar, E.; Garcia-Parrilla, M.C. Melatonin Is Synthesised by Yeast during Alcoholic Fermentation in Wines. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1608–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocadaǧli, T.; Yilmaz, C.; Gökmen, V. Determination of Melatonin and Its Isomer in Foods by Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Food Chem. 2014, 153, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevia, D.; Mayo, J.C.; Tan, D.-X.; Rodriguez-Garcia, A.; Sainz, R.M. Melatonin Enhances Photo-Oxidation of 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein by an Antioxidant Reaction That Renders N1-Acetyl-N2-Formyl-5-Methoxykynuramine (AFMK). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, X.; Mazza, G. Simultaneous Analysis of Serotonin, Melatonin, Piceid and Resveratrol in Fruits Using Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 3890–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Brewery Convention Analytica. EBC Section 13 Sensory Analysis Method 13.0. In EBC Methods of Analysis; Fachverlag Hans Carl: Nürnberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Brewery Convention Analytica. EBC Section 13 Sensory Analysis Method 13.12. In EBC Methods of Analysis; Fachverlag Hans Carl: Nürnberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- European Brewery Convention Analytica. EBC Section 13 Sensory Analysis Method 13.4. In EBC Methods of Analysis; Fachverlag Hans Carl: Nürnberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Viejo, C.G.; Fuentes, S.; Torrico, D.D.; Godbole, A.; Dunshea, F.R. Chemical Characterization of Aromas in Beer and Their Effect on Consumers Liking. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Brewery Convention Analytica. EBC Section 13 Sensory Analysis Method 13.10. In EBC Methods of Analysis; Fachverlag Hans Carl: Nürnberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, C.; Quain, D. Brewing Yeast and Fermentation; Boulton, C., Quain, D., Eds.; Blackwell Science Ltd: Oxford, UK, 2006; ISBN 9780470999417. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, D.; Boulton, C.; Brookes, P.; Stevens, R. Brewing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; Volume 1, ISBN 978-0-8493-2547-2. [Google Scholar]

- Oka, K.; Hayashi, T.; Matsumoto, N.; Yanase, H. Decrease in Hydrogen Sulfide Content during the Final Stage of Beer Fermentation Due to Involvement of Yeast and Not Carbon Dioxide Gas Purging. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2008, 106, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.J.L.; Olsson, L.; Rønnow, B.; Mikkelsen, J.D.; Nielsen, J. Alleviation of Glucose Repression of Maltose Metabolism by MIG1 Disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 4441–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Federoff, H.J.; Eccleshall, T.R.; Marmur, J. Carbon Catabolite Repression of Maltase Synthesis in Saccharomyces carlsbergensis. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 156, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guido, L.F. Brewing and Craft Beer. Beverages 2019, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hellwig, M.; Beer, F.; Witte, S.; Henle, T. Yeast Metabolites of Glycated Amino Acids in Beer. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 7451–7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, E.; Becker, T.; Gastl, M. Turbidity and Haze Formation in Beer—Insights and Overview. J. Inst. Brew. 2010, 116, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, P.S.; Baxter, E.D. Beer: Quality, Safety and Nutritional Aspects; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2001; ISBN 0854045880. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J.; Fox, G. Novel Non-Cerevisiae Saccharomyces Yeast Species Used in Beer and Alcoholic Beverage Fermentations. Fermentation 2020, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdaniewicz, M.; Satora, P.; Pater, A.; Bogacz, S. Low Lactic Acid-Producing Strain of Lachancea Thermotolerans as a New Starter for Beer Production. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, A.E. Brewing Microbiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 9781782423317. [Google Scholar]

- Branduardi, P.; Sauer, M.; De Gioia, L.; Zampella, G.; Valli, M.; Mattanovich, D.; Porro, D. Lactate Production Yield from Engineered Yeasts Is Dependent from the Host Background, the Lactate Dehydrogenase Source and the Lactate Export. Microb. Cell Fact. 2006, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Popescu, V.; Soceanu, A.; Dobrinas, S.; Stanciu, G. A Study of Beer Bitterness Loss during the Various Stages of the Romanian Beer Production Process. J. Inst. Brew. 2013, 119, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamforth, C.W. Beer and Health. In Beer; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 229–253. ISBN 9780126692013. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, D.R.J.; McGuinness, J.D.; Rennie, H. The Losses of Bitter Substances during Fermentation. J. Inst. Brew. 1972, 78, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Madrera, R.; Pando Bedriñana, R.; Suárez Valles, B. Evaluation of Indigenous Non-Saccharomyces Cider Yeasts for Use in Brewing. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillos, F.A.; Gibson, B.; Grijalva-Vallejos, N.; Krogerus, K.; Nikulin, J. Bioprospecting for Brewers: Exploiting Natural Diversity for Naturally Diverse Beers. Yeast 2019, 36, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadez, N.; Smith, M.T. Hanseniaspora Zikes (1912). In The Yeasts. A Taxonomic Study; Kurtzman, C.P., Fell, J.W., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 421–434. ISBN 9780444521491. [Google Scholar]

- Lachance, M.A.; Boekhout, T.; Scorzetti, G.; Fell, J.W.; Kurtzman, C.P. Candida berkhout (1923). In Yeasts. A Taxonomic Study; Kurtzman, C.P., Fell, J.W., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 987–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachance, M.A. Metschnikowia Kamienski (1899); Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, ISBN 9780444521491. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman, C.P. Torulaspora Lindner (1904); Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, ISBN 9780444521491. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman, C.P. Wickerhamomyces Kurtzman, Robnett & Basehoar-Powers (2008); Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, ISBN 9780444521491. [Google Scholar]

- Langstaff, S.A.; Lewis, M.J. The Mouthfeel of Beer—A REVIEW. J. Inst. Brew. 1993, 99, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachance, M.A.; Kurtzman, C.P. Lachancea Kurtzman (2003); Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, ISBN 9780444521491. [Google Scholar]

- Bellut, K.; Michel, M.; Hutzler, M.; Zarnkow, M.; Jacob, F.; De Schutter, D.P.; Daenen, L.; Lynch, K.M.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Investigation into the Potential of Lachancea fermentati Strain KBI 12.1 for Low Alcohol Beer Brewing. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2019, 77, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callejo, M.J.; García Navas, J.J.; Alba, R.; Escott, C.; Loira, I.; González, M.C.; Morata, A. Wort Fermentation and Beer Conditioning with Selected Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts in Craft Beers. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einfalt, D. Barley-Sorghum Craft Beer Production with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Torulaspora delbrueckii and Metschnikowia pulcherrima Yeast Strains. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larroque, M.N.; Carrau, F.; Fariña, L.; Boido, E.; Dellacassa, E.; Medina, K. Effect of Saccharomyces and Non-Saccharomyces Native Yeasts on Beer Aroma Compounds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 337, 108953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.M. Pichia anomala: Cell Physiology and Biotechnology Relative to Other Yeasts. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2011, 99, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourbon-Melo, N.; Palma, M.; Rocha, M.P.; Ferreira, A.; Bronze, M.R.; Elias, H.; Sá-Correia, I. Use of Hanseniaspora guilliermondii and Hanseniaspora opuntiae to Enhance the Aromatic Profile of Beer in Mixed-Culture Fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Microbiol. 2021, 95, 103678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budroni, M.; Zara, G.; Ciani, M.; Comitini, F. Saccharomyces and Non-Saccharomyces Starter Yeasts. In Brewing Technology; InTech: London, UK, 2017; pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Siebert, K.J. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Modeling of Alcohol, Ester, Aldehyde, and Ketone Flavor Thresholds in Beer from Molecular Features. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 3057–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, N.; Mendes, F.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; Hogg, T.; Vasconcelos, I. Heavy Sulphur Compounds, Higher Alcohols and Esters Production Profile of Hanseniaspora uvarum and Hanseniaspora guilliermondii Grown as Pure and Mixed Cultures in Grape Must. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 124, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhuo, X.; Hu, L.; Zhang, X. Effects of Crude β-Glucosidases from Issatchenkia terricola, Pichia kudriavzevii, Metschnikowia pulcherrima on the Flavor Complexity and Characteristics of Wines. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, F.; Caldeira, M.; Câmara, J.S. Development of a Dynamic Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction Procedure Coupled to GC-QMSD for Evaluation the Chemical Profile in Alcoholic Beverages. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 609, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson Witrick, K.; Duncan, S.E.; Hurley, K.E.; O’Keefe, S.F. Acid and Volatiles of Commercially-Available Lambic Beers. Beverages 2017, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madrera, R.R.; Bedriñana, R.P.; Valles, B.S. Production and Characterization of Aroma Compounds from Apple Pomace by Solid-State Fermentation with Selected Yeasts. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 1342–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olšovská, J.; Vrzal, T.; Štěrba, K.; Slabý, M.; Kubizniaková, P.; Čejka, P. The Chemical Profiling of Fatty Acids during the Brewing Process. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engan, S. Organoleptic Threshold Values of Some Organic Acids in Beer. J. Inst. Brew. 1974, 80, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilgaard, M.C. Prediction of Flavor Differences between Beers from Their Chemical Composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1982, 30, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, M.G.; Pretorius, I.S. Yeast and Its Importance to Wine Aroma. Underst. Wine Chem. 2000, 21, 97–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romano, P.; Suzzi, G. Origin and Production of Acetoin during Wine Yeast Fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giorello, F.; Valera, M.J.; Martin, V.; Parada, A.; Salzman, V.; Camesasca, L.; Fariña, L.; Boido, E.; Medina, K.; Dellacassa, E.; et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Basis of Hanseniaspora Vineae’s Impact on Flavor Diversity and Wine Quality. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01959-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arslan, E.; Çelik, Z.D.; Cabaroğlu, T. Effects of Pure and Mixed Autochthonous Torulaspora delbrueckii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on Fermentation and Volatile Compounds of Narince Wines. Foods 2018, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaquero, C.; Izquierdo-Cañas, P.M.; Mena-Morales, A.; Marchante-Cuevas, L.; Heras, J.M.; Morata, A. Use of Lachancea thermotolerans for Biological vs. Chemical Acidification at Pilot-Scale in White Wines from Warm Areas. Fermentation 2021, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterckx, F.L.; Missiaen, J.; Saison, D.; Delvaux, F.R. Contribution of Monophenols to Beer Flavour Based on Flavour Thresholds, Interactions and Recombination Experiments. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1679–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farlow, A.; Long, H.; Arnoux, S.; Sung, W.; Doak, T.G.; Nordborg, M.; Lynch, M. The Spontaneous Mutation Rate in the Fission Yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 2015, 201, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vigentini, I.; Gardana, C.; Fracassetti, D.; Gabrielli, M.; Foschino, R.; Simonetti, P.; Tirelli, A.; Iriti, M. Yeast Contribution to Melatonin, Melatonin Isomers and Tryptophan Ethyl Ester during Alcoholic Fermentation of Grape Musts. J. Pineal Res. 2015, 58, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcillo-Parra, M.Á.; Beltran, G.; Mas, A.; Torija, M.-J. Effect of Several Nutrients and Environmental Conditions on Intracellular Melatonin Synthesis in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postigo, V.; García, M.; Cabellos, J.M.; Arroyo, T. Wine Saccharomyces Yeasts for Beer Fermentation. Fermentation 2021, 7, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, J.; Skene, D.J. Melatonin as a Chronobiotic. Sleep Med. Rev. 2005, 9, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Srinivasan, V.; Maestroni, G.J.M.; Cardinali, D.P.; Poeggeler, B.; Hardeland, R. Melatonin. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 2813–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osburn, K.; Amaral, J.; Metcalf, S.R.; Nickens, D.M.; Rogers, C.M.; Sausen, C.; Caputo, R.; Miller, J.; Li, H.; Tennessen, J.M.; et al. Primary Souring: A Novel Bacteria-Free Method for Sour Beer Production. Food Microbiol. 2018, 70, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanbeneden, N.; Gils, F.; Delvaux, F.; Delvaux, F.R. Formation of 4-Vinyl and 4-Ethyl Derivatives from Hydroxycinnamic Acids: Occurrence of Volatile Phenolic Flavour Compounds in Beer and Distribution of Pad1-Activity among Brewing Yeasts. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Yeast Strain | Species | Maltose Assimilation | H2S Production Type | Yeast Strain | Species | Maltose Assimilation | H2S Production Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLI 1 | Wickerhamomyces anomalus | + | I | CLI 650 | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | + | II |

| CLI 3 | Hanseniaspora vineae | - | III | CLI 679 | Pichia membranefaciens | - | II |

| CLI 64 | Torulaspora delbrueckii | - | II | CLI 691 | Zygosaccharomyces bailii | - | I |

| CLI 68 | Metschnikowia pulcherrima | - | I | CLI 894 | Lachancea thermotolerans | - | II |

| CLI 72 | Kloeckera spp. | - | II | CLI 900 | Torulaspora delbrueckii | - | II |

| CLI 101 | Metschnikowia pulcherrima | - | I | CLI 902 | Torulaspora delbrueckii | - | III |

| CLI 120 | Torulaspora delbrueckii | - | II | CLI 918 | Torulaspora delbrueckii | - | III |

| CLI 186 | Torulaspora delbrueckii | - | II | CLI 920 | Candida stellata | + | II |

| CLI 190 | Hanseniaspora guilliermondii | + | I | CLI 921 | Hanseniaspora guilliermondii | - | II |

| CLI 194 | Hanseniaspora valbyensis | - | III | CLI 996 | Lachancea thermotolerans | + | II |

| CLI 219 | Metschnikowia pulcherrima | - | I | CLI 1028 | Wickerhamomyces anomalus | - | II |

| CLI 225 | Hanseniaspora guilliermondii | - | III | CLI 1232 | Lachancea thermotolerans | + | III |

| CLI 330 | Torulaspora delbrueckii | - | III | 6-5A | Wickerhamomyces anomalus | - | II |

| CLI 417 | Hanseniaspora valbyensis | - | II | 9-6C | Lachancea thermotolerans | + | III |

| CLI 457 | Metschnikowia pulcherrima | - | II | 7A-3A | Torulaspora delbrueckii | - | III |

| CLI 512 | Hanseniaspora guilliermondii | - | II | 19A-10B | Torulaspora delbrueckii | - | III |

| CLI 622 | Zygosaccharomyces bailii | - | IV | 25A-2A | Candida sorbosa | - | IV |

| CLI 623 | Zygosaccharomyces bailii | - | I | 17B-10A | Candida stellata | - | III |

| Yeast Strain | Residual Sugars (g L−1) | Lactic Acid (ppm) | Colour (EBC) | Bitterness (IBU) | Alcohol (% v/v) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLI 3 | 74.50 ± 3.50 ab | 176.50 ± 26.50 ef | 12.50 ± 1.53 defg | 24.90 ± 1.30 abcdef | ≤1.00 d |

| CLI 190 | 63.00 ± 0.00 de | 152.50 ± 0.58 f | 12.50 ± 1.53 defg | 27.75 ± 0.75ab | ≤1.00 d |

| CLI 194 | 66.00 ± 3.00 cde | 177.00 ± 6.00 ef | 13.50 ± 1.53 bcdef | 23.75 ± 1.25 bcdef | ≤1.00 d |

| CLI 225 | 69.50 ± 4.51 bcd | 176.00 ± 26.00 ef | 12.00 ± 1.00 efg | 24.95 ± 1.55 abcde | ≤1.00 d |

| CLI 457 | 60.00 ± 0.00 e | 175.50 ± 25.50 ef | 16.00 ± 0.00 bc | 21.50 ± 1.60 def | ≤1.00 d |

| CLI 512 | 68.50 ± 0.58 bcd | 193.00 ± 17.00 def | 13.00 ± 0.00 cdef | 20.35 ± 1.15 f | 1.1 ± 0.10 d |

| CLI 650 | ≤15.00 f | 274.00 ± 39.00 c | 15.50 ± 1.53 bcd | 22.80 ± 1.00 cdef | 4.95 ± 0.15 b |

| CLI 894 | 78.00 ± 3.00 a | 230.5 ± 21.50 cde | 15.50 ± 0.58 bcd | 25.75 ± 1.24 abcd | 1.10 ± 0.10 d |

| CLI 902 | 79.00 ± 0.00 a | 166.50 ± 16.50 ef | 16.00 ± 0.00 bc | 22.30 ± 1.90 cdef | 1.35 ± 0.15 d |

| CLI 918 | 64.50 ± 0.58 cde | 150.00 ± 0.00 f | 22.00 ± 0.00 a | 24.00 ± 0.90 bcdef | ≤1.00 d |

| CLI 920 | 60.00 ± 0.00 e | 190.00 ± 0.00 ef | 21.50 ± 0.58 a | 23.25 ± 0.05 bcdef | ≤1.00 d |

| CLI 921 | 67.00 ± 4.00 bcde | 263.00 ± 37.00 cd | 12.50 ± 0.58 defg | 24.65 ± 0.85 bcdef | 1.02 ± 0.20 d |

| CLI 996 | 17.50 ± 1.53 f | 277.00 ± 17.00 c | 10.50 ± 1.53 fg | 26.50 ± 1.60 abc | 5.600 ± 0.70 ab |

| CLI 1028 | 69.00 ± 7.00 bcd | 196.00 ± 0.00 def | 11.50 ± 0.58 efg | 29.30 ± 2.10 a | ≤1.0 d |

| CLI 1232 | 15.50 ± 0.58 f | 3,283.50 ± 23.50 a | 9.50 ± 1.53 g | 13.50 ± 0.30 g | 5.70 ± 0.40 a |

| 6-5A | 72.00 ± 4.00 abc | 151.50 ± 1.53 f | 13.50 ± 1.53 bcdef | 23.40 ± 1.40 cdef | 1.10 ± 0.10 d |

| 9-6C | ≤15.00 f | 2,720.50 ± 43.50 b | 16.50 ± 0.58 b | 15.50 ± 0.80 g | 3.85 ± 0.05 c |

| 7A-3A | 64.00 ± 0.00 cde | 172.00 ± 22.00 ef | 12.00 ± 1.00 efg | 24.30 ± 1.80 bcdef | ≤1.00 d |

| S-04 | ≤15.00 f | 263.33 ± 37.29 cd | 14.30 ± 1.53 bcde | 21.10 ± 3.32 ef | 6.32 ± 0.58 a |

| Yeast Strain | Higher Alcohols | Esters | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isobutanol | Isoamyl Alcohol | 1-Hexanol | β-Phenylethanol | Ethyl Butyrate | Ethyl Isovalerate | Isoamyl Acetate | Ethyl Hexanoate | Ethyl Lactate | 2-Phenethyl Acetate | |

| CLI 3 | 4.06 ± 0.99 gh | 19.34 ± 1.04 efg | nd | 5.25 ± 0.45 ghi | 0.32 ± 0.04 bc | 0.03 ± 0.03 c | nd | 0.10 ± 0.00 c | nd | nd |

| CLI 190 | 5.15 ± 1.67 fgh | 20.75 ± 0.65 efg | 1.20 ± 0.30 a | 9.70 ± 0.70 efghi | 0.01 ± 0.00 f | 0.03 ± 0.03 c | nd | 0.10 ± 0.04 c | nd | 0.03 ± 0.01 a |

| CLI 194 | 5.99 ± 0.45 efg | 16.44 ± 1.23 fg | nd | 20.73 ± 1.55 cd | 0.47 ± 0.04 b | 0.06 ± 0.05 a | nd | 0.01 ± 0.00 c | nd | nd |

| CLI 225 | 4.60 ± 2.40 fgh | 13.64 ± 1.44 fg | 1.20 ± 0.20 a | 3.82 ± 0.82 hi | 0.04 ± 0.00 f | 0.03 ± 0.03 bc | nd | 0.04 ± 0.01 c | nd | 0.00 ±0.00 c |

| CLI 457 | 8.79 ± 0.09 de | 13.39 ± 0.13 fg | nd | 0.61 ± 0.01 i | nd | 0.06 ± 0.00 bc | nd | 0.10 ± 0.00 c | nd | nd |

| CLI 512 | 4.40 ± 0.04 fgh | 19.28 ± 0.19 efg | nd | 7.32 ± 0.07 fghi | 0.03 ± 0.00 f | nd | 0.04 ± 0.00 c | 0.04 ± 0.00 c | nd | nd |

| CLI 650 | 8.02 ± 0.87 def | 42.01 ± 2.51 bcd | nd | 13.98 ± 0.98 defg | 0.24 ± 0.05 cde | 0.05 ± 0.05 bc | 0.16 ± 0.00 c | 0.18 ± 0.15 bc | nd | 0.00 ± 0.00 c |

| CLI 894 | 10.44 ± 0.20 cd | 35.69 ± 1.69 bcde | 1.22 ± 0.22 a | 14.46 ± 1.46 defg | 0.11 ± 0.01 def | 0.03 ± 0.03 c | nd | 0.04 ± 0.00 c | nd | nd |

| CLI 902 | 4.27 ± 1.45 gh | 46.10 ± 1.09 abc | nd | 20.90 ± 0.48 cd | 0.04 ± 0.01 f | 0.04 ± 0.04 bc | nd | 0.34 ± 0.31 abc | nd | 0.00 ± 0.00 c |

| CLI 918 | 5.39 ± 0.05 efgh | 40.83 ± 0.40 bcd | nd | 18.43 ± 0.19 cde | nd | 0.08 ± 0.00 bc | nd | 0.74 ± 0.01 a | nd | 0.00 ± 0.00 bc |

| CLI 920 | 22.56 ± 0.22 a | 25.47 ± 0.25 defg | nd | 3.52 ± 0.03 hi | nd | nd | nd | 0.03 ± 0.00 c | nd | nd |

| CLI 921 | 1.86 ± 0.92 h | 13.45 ± 1.46 fg | 1.16 ± 0.26 a | 5.81 ± 0.81 ghi | 0.17 ± 0.07 cdef | 0.04 ± 0.04 bc | nd | 0.10 ± 0.00 c | nd | 0.00 ± 0.00 c |

| CLI 996 | 10.04 ± 1.11 cd | 36.07 ± 12.48 bcde | nd | 27.07 ± 0.40 bc | 0.29 ± 0.09 bcd | 0.12 ± 0.02 b | 0.39 ± 0.19 a | 0.60 ± 0.57 ab | nd | 0.01 ±0.00 b |

| CLI 1028 | 4.55 ± 0.56 fgh | 24.33 ± 1.33 defg | nd | 16.77 ± 1.77 def | 0.06 ± 0.01 ef | 0.03 ± 0.03 bc | nd | 0.17 ± 0.10 bc | nd | nd |

| CLI 1232 | 15.59 ± 0.03 b | 9.44 ± 0.56 g | nd | 35.82 ± 1.82 ab | 1.22 ± 0.23 a | 0.06 ± 0.02 bc | nd | 0.23 ± 0.04 bc | 13.85 ± 1.15 b | nd |

| 6-5A | 3.54 ± 0.95 gh | 15.86 ± 0.86 fg | nd | 10.60 ± 0.60 efgh | nd | 0.08 ± 0.00 bc | nd | 0.14 ± 0.13 bc | nd | 0.00 ± 0.00 c |

| 9-6C | 19.29 ± 1.10 a | 53.67 ± 3.02 ab | nd | 8.52 ± 0.54 fghi | nd | 0.08 ± 0.02 bc | 0.05 ± 0.00 c | 0.27 ± 0.07 abc | 20.51 ± 0.51 a | nd |

| 7A-3A | 1.85 ± 0.15 h | 28.09 ± 1.97 cdef | 1.20 ± 0.20 a | 15.81 ± 0.81 def | 0.01 ± 0.01 f | 0.03 ± 0.03 bc | nd | 0.02 ± 0.01 c | nd | 0.00 ± 0.00 c |

| S-04 | 12.25 ± 2.60 bc | 60.66 ± 18.16 a | 1.45 ± 0.03 a | 44.72 ± 10.75 a | 0.45 ± 0.11 b | nd | 0.39 ± 0.19 b | 0.06 ± 0.04 c | 0.58 ± 0.83 c | nd |

| Yeast Strain | Fatty Acids | Aldehydes/Ketones | Guaiacol | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butyric Acid | Hexanoic Acid | Octanoic Acid | Decanoic Acid | Acetoin | Benzaldehyde | Phenyl Acetaldehyde | γ- Butyrolactone | ||

| CLI 3 | 0.01 ± 0.00 c | 0.18 ± 0.08 d | 0.02 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 8.24 ± 0.74 ab | 0.04 ± 0.01 cd | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | nd | nd |

| CLI 190 | nd | 0.25 ± 0.04 cd | 0.02 ± 0.02 b | 0.01 ± 0.01 b | 10.03 ± 1.03 a | 0.57 ± 0.07 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 3.75 ± 2.25 ab | 0.10 ± 0.01 cd |

| CLI 194 | 3.89 ± 0.29 ab | 0.16 ± 0.01 d | 0.06 ± 0.00 b | 0.02 ± 0.00 b | nd | nd | nd | 0.58 ± 0.04 fgh | 0.07 ± 0.01 de |

| CLI 225 | 4.67 ± 0.67 a | 0.31 ± 0.06 cd | 0.03 ± 0.03 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 7.27 ± 1.07 bc | 0.57 ± 0.07 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.36 ± 0.06 gh | 0.36 ± 0.06 a |

| CLI 457 | 0.05 ± 0.00 c | 0.24 ± 0.00 cd | 0.04 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 3.59 ± 0.04 ef | nd | nd | 2.64 ± 0.03 bcd | nd |

| CLI 512 | nd | 2.61 ± 0.02 a | nd | nd | 9.43 ± 0.09 a | nd | nd | 0.12 ± 0.00 h | 0.32 ± 0.00 a |

| CLI 650 | 0.03 ± 0.03 c | 0.65 ± 0.01 bcd | 0.10 ± 0.10 b | 0.02 ± 0.02 b | 1.49 ± 0.49 hi | 0.10 ± 0.00 bc | nd | 1.81 ± 0.81 cdef | 0.02 ± 0.02 e |

| CLI 894 | 4.99 ± 0.99 a | 1.01 ± 0.21 b | 0.02 ± 0.02 b | 0.01 ± 0.01 b | 8.83 ± 0.83 ab | nd | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 1.81 ± 0.81 cdef | 0.16 ± 0.06 bc |

| CLI 902 | 2.46 ± 2.46 b | 0.61 ± 0.14 bcd | 0.02 ± 0.02 b | 0.02 ± 0.02 b | 5.66 ± 0.66 cd | nd | nd | 2.06 ± 0.56 cde | 0.01 ± 0.00 e |

| CLI 918 | 0.05 ± 0.00 c | 0.31 ± 0.00 cd | 0.02 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 5.22 ± 0.05 de | nd | nd | 2.65 ± 0.03 bcd | nd |

| CLI 920 | nd | 0.15 ± 0.00 d | 0.02 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 1.52 ± 0.02 ghi | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| CLI 921 | 0.03 ± 0.03 c | 0.28 ± 0.16 cd | 0.08 ± 0.08 b | 0.03 ± 0.03 b | 4.03 ± 1.03 def | 0.13 ± 0.03 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 1.21 ± 0.21 efgh | 0.19 ± 0.04 b |

| CLI 996 | 0.04 ± 0.04 c | 0.73 ± 0.40 bc | 1.05 ± 0.23 a | 0.04 ± 0.04 b | 5.91 ± 0.35 cd | 0.01 ± 0.01 d | nd | 2.06 ± 0.56 cde | 0.03 ± 0.01 de |

| CLI 1028 | 0.02 ± 0.02 c | 0.37 ± 0.07 cd | 0.03 ± 0.03 b | 0.01 ± 0.01 b | nd | 0.11 ± 0.01 bc | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 1.64 ± 0.98 defg | 0.02 ± 0.01 de |

| CLI 1232 | nd | 0.60 ± 0.10 bcd | 0.05 ± 0.05 b | 0.07 ± 0.07 b | nd | 0.13 ± 0.03 b | nd | 3.13 ± 0.63 abc | nd |

| 6-5A | 0.06 ± 0.00 c | 0.26 ± 0.11 cd | 0.06 ± 0.00 b | 0.07 ± 0.00 b | 2.74 ± 1.24 fgh | nd | nd | 4.18 ± 0.18 a | nd |

| 9-6C | 3.78 ± 0.78 ab | 0.61 ± 0.17 bcd | 0.03 ± 0.03 b | 0.01 ± 0.01 b | nd | nd | nd | 1.81 ± 0.81 cdef | nd |

| 7A-3A | 0.03 ± 0.03 c | 0.21 ± 0.09 d | 0.03 ± 0.03 b | 0.01 ± 0.01 b | 3.53 ± 0.54 efg | nd | nd | nd | 0.04 ± 0.02 de |

| S-04 | nd | 0.62 ± 0.39 bcd | 1.08 ± 0.54 a | 0.31 ± 0.07 a | 5.42 ± 0.98 cde | nd | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.57 ± 0.01 fgh | 0.06 ± 0.05 de |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Postigo, V.; Sánchez, A.; Cabellos, J.M.; Arroyo, T. New Approaches for the Fermentation of Beer: Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Wine. Fermentation 2022, 8, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8060280

Postigo V, Sánchez A, Cabellos JM, Arroyo T. New Approaches for the Fermentation of Beer: Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Wine. Fermentation. 2022; 8(6):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8060280

Chicago/Turabian StylePostigo, Vanesa, Ana Sánchez, Juan Mariano Cabellos, and Teresa Arroyo. 2022. "New Approaches for the Fermentation of Beer: Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Wine" Fermentation 8, no. 6: 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8060280

APA StylePostigo, V., Sánchez, A., Cabellos, J. M., & Arroyo, T. (2022). New Approaches for the Fermentation of Beer: Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Wine. Fermentation, 8(6), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8060280