The proposed tax system is deduced from five guiding principles that form the basis of a mathematical framework. This section starts with the conceptual framework, in which the rationale for the guiding principles is discussed. Recognizing that there are different perspectives, each principle is rationalized by questioning whether it has universal appeal. The goal is to transcend political biases as much as possible by rejecting what is not universal. An effort is made to distill an income tax system into essential elements. A mathematical framework is then developed with parameters that encapsulate a family of income tax systems that differ by the parameter values set by the state of the economy. This allows governments to adapt to society’s needs over time.

2.1. Conceptual Framework

In a bottom-up approach, five guiding principles for a holistic tax system are first listed. The rationale for each principle is then discussed as subsections. These principles shape the tax system by imposing constraints, which leads to a tax system that is easily parameterized within a mathematical framework. The principles are listed as:

Income of all types is taxed at the same rate, independent of the income level.

A single tax rate adjusts to ensure government fiscal stability.

Government transfer is only used to establish a minimum standard of living.

Three types of tax deductions incentivize wealth accumulation.

- (a)

A basic deduction to offset living expenses.

- (b)

Itemized deductions that promote better standard of living.

- (c)

Capital loss deductions that promote economic growth.

Tax deductions cannot be applied on government transfer.

2.1.1. Income of All Types Is Taxed at the Same Rate, Independent of the Income Level

Taxing one type of income differently from another creates social discrimination. For example, it could be argued that income from work done by a teacher should be taxed twice as high as income from work done by a welder. Intrinsic to this argument is that the value of the work of a welder is more important than a teacher, or perhaps simply to offset the risks inherent in welding. However, an objective truth of this differentiation is not self-evident, as many teachers would argue otherwise. Many of these comparisons can be made, all of which end with arbitrary conclusions. Logic suggests that it is not the place of government to judge the intrinsic value of income beyond the definition of legal and illegal activities. In practice, assigning different tax rates to different types of income creates a complicated system that leads to endless debate, because there is no universal truth for all cultures, all types of economy, all types of government, and certainly not a constant in time. The same logic is true when it comes to distinguishing income from labor versus investments or other forms of income, such as gifts, winnings, insurance or inheritance.

For free-market economies, the amount of income a person generates in terms of salary or return on investments determines the value society attaches to occupation and investment. Income is determined by tangible factors, such as supply and demand, investment decisions, the wealth potential of occupations, and the desire of an individual to be wealthy. For example, the income of a surgeon can be higher or lower than a professional athlete, depending on various factors. Therefore, the allocation of different tax rates on different types or income levels must be rejected. A household with orders of magnitude more income than another will pay proportionally that much more tax, which does not discriminate on income levels. Although sale taxes can coexist with this principle, no other form of taxation of a person’s income is allowed. For example, this means that in the US, the separate payroll tax must be eliminated, as there can only be one tax rate on income, which is comprehensively taken care of by the income tax system within a holistic approach.

2.1.2. A Single Tax Rate Adjusts to Ensure Government Fiscal Stability

A pertinent question is: What should the single tax rate be? A constant value (say 9%) could be argued as optimal, but this value is not self-evident. Indeed, any specific value would not be universally optimal for all cultures, economies, governments, and for all time, as the state of the economy fluctuates over time. Therefore, a variable tax rate that adapts to the revenue needed to cover projected government spending is required. A dynamic tax rate allows a government to control fiscal stability while adapting to short- and long-term economic conditions. Cycles of high and low tax rates induce an elastic response to balancing budgets (with limited liability), which ensures reliability in public services and mitigates the accumulation of long-term debt. Both of these attributes are necessary for long-term stability of society.

It is worth pointing out that policy makers have responsibility for developing debt accumulation or reduction plans. Regardless of the directions that policy makers decide, the adjustable tax rate makes tax revenue collecting responsive to government policies. For example, if more funding is appropriated toward infrastructure or defense, the single tax rate will increase, and society can monitor and judge the benefits for increased taxes. In summary, a single tax rate offers transparency in government spending, and in combination with other social-economic measures, the value that the government attaches to society’s well-being becomes transparent.

2.1.3. Government Transfer Is Only Used to Establish a Minimum Standard of Living

For what reason, if any, should government transfer be used to supplement household income? Arguably, government transfers should not be used for anything other than to help a household achieve a minimal standard of living. This principle does not exclude government support in other forms, such as tax deductions and public services. For example, government spending on entitled health care, education, or other infrastructure does not constitute government transfer. However, public services must be independent of the income level, void of any income qualification.

Providing public services to poor subpopulations is unnecessary, because the poorest households will live at the poverty line, which sets a minimum standard of living. Rather than designing social programs to help the poor, public services should be designed to help society. This paradigm shift of shared interest will ensure that social programs are of high quality. It is worth noting that public services will reduce poverty by reducing basic living costs. Conversely, the poverty line rises as free public services decrease. Importantly, this principle prohibits the use of government transfers for unemployment or retirement compensation. Consequently, policy decisions will involve common interests in diverse and large segments of the population.

It is obvious that if government transfers are used to subsidize households for anything other than supporting a minimum standard of living, an arbitrary number of good reasons to redistribute income will lead to a complex tax system that is not universal. Why, however, should government redistribute income to set a minimum standard of living? Elimination of poverty is a singular case that appeals universally because of the innate human desire to live healthy and securely with dignity. This institutes the responsibility of the government to provide the means for all individuals in society to live securely with dignity over countless generations.

In practice, the poverty line must be set to balance competing factors. The poverty line should not be set too low, because more productivity in the entire population will result if society as a whole has a functional standard of living. Conversely, if the poverty line is set too high, the tax rate will rise too high, stifling economic growth. As such, the minimum standard of living that society can tolerate sets the poverty line for households. Although the way policy makers define this poverty line is left open, it must be based on income (not savings or wealth). Government transfers supplement income to establish a minimum standard of living as a safety net. If a household starts with considerable assets and then unexpectedly finds itself without income, this household can survive at the poverty line, with basic needs fulfilled. Moreover, this household can use its savings, albeit a finite resource, to live a higher standard of living.

A consequence of having one specific reason for government transfer is that the government has minimal involvement in a free market. As another example, if a household with a large accumulation of debt suddenly loses its income, it is likely to lose its possessions if an agreement with its lenders cannot be reached. Responsibility and risk tolerances exist between lenders and households taking loans. Government transfer is used only to maintain a minimum standard of living, and this results in keeping the net amount of transfer to a minimum, and hence keeps the tax rate to a minimum.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an unfortunate example of a situation in which the victory tax system maintains a stable economy during a crisis. Households automatically receive government transfers when their income falls below the poverty line due to job loss. Because of guaranteed basic income, the debate in the US on the scope of COVID-19 relief packages would be unnecessary since government transfer creates a safety net of security. Nevertheless, financial losses from businesses and households would be expected. While many lenders would be eager to force foreclosure, other lenders would use unfortunate events as a growth opportunity to attract new (sound) customers by covering businesses from bankruptcy and households from personal losses. The free market would solve the vast majority of the problems, with government regulations perhaps requiring debt collectors to exercise patience. As jobs reemerge, low-income households quickly increase their after-tax income, avoiding long-term economic stagnation.

2.1.4. Three Types of Tax Deductions Incentivize Wealth Accumulation

Tax deductions are used to reduce the tax burden on households for various reasons. For a certain amount of revenue to be collected, reducing the tax burden on a subset of households requires other households to pay disproportionately higher taxes. Of course, different tax rates applied to different income levels or types cause disproportionate tax burdens. However, even if a single tax rate is applied to all income levels and types (e.g., nominally a flat tax), tax deductions create a non-flat ETR dependent on household income. Importantly, different types of tax deductions produce different relative benefits for households at different income levels. For example, the basic tax deduction that offsets minimum living expenses provides proportionately more benefit to low-income households. Itemized deductions predominately help households with middle-range income. Capital loss deductions on investment losses primarily benefit high-income households. In fact, low-income households cannot capitalize on capital loss tax deductions.

Among the different types of tax deductions, a balance should be sought between benefits versus the disproportionate tax burdens created across the income spectrum of households. The structure of tax deductions should benefit society, as taxpayers seek to obtain the maximum after-tax income possible from their own interests. Tax deductions therefore offer specific redistribution mechanisms for government support to motivate households to accumulate wealth, which in turn maintains a stable and growing economy. The rationale for the basic, itemized, and capital-loss tax deductions is discussed next, while key variables for the victory tax system are introduced.

Basic tax deduction: A minimum income is needed to live functionally in modern society. In the past, most people could live on natural resources or farm land. Unless free public services take the place of natural resources, job loss literally becomes life threatening. Hence, a basic deduction, , is incorporated to cover minimum living costs for a household. Although is a free parameter, it is appropriately related to the poverty line. Furthermore, should only depend on the number of dependents in a household and the cost for necessities (which is location dependent), as its sole purpose is to offset minimal living costs in the context of a social norm.

Itemized tax deduction: To incentivize financial independence, optional itemized deductions are allowed. Itemized deductions offer the government flexibility in the tax code to encourage certain measures, such as buying a house, accumulating a retirement portfolio, compensating costs for professional training, education or medical needs, or making donations to charities. As such, itemized tax deductions create self-interest incentives for households to take measures that also benefit society as a whole. The net itemized deduction,

, is incorporated into the general framework of the victory tax. The total income that can be deducted is capped at a maximum. Setting a maximum deduction prevents all households from not paying tax. Two methods are used to set the maximum total deduction. A maximum deduction,

, and a maximum percentage,

, of net income,

. The total deduction,

, allowed by a household is given by:

For a household with a net income above the poverty line with no itemized deductions, its taxable income,

is given as:

The equation for taxable income developed thus far is easy to understand. The combined total of basic and itemized deductions cannot exceed the maximum allowed deduction, nor a maximum percentage of income. Once the total deduction, , is determined, it will be used to reduce net income in order to achieve the taxable income. However, if the deduction is greater than the net income, , then the taxable income, , is set to zero, as it cannot be negative. The net income will be precisely defined after capital loss deductions are considered.

Capital loss deduction: To encourage households to increase their wealth through investments, capital loss deductions are used to mitigate risk. It is self-evident that government cannot rescue all households from financial loss. Hence, under what circumstance, if any, should government aid households to recover lost wealth? Imagine an individual that invests $100,000 in a company, and subsequently loses this investment due to the bankruptcy of that company. Another individual buys a $100,000 painting, which is inadvertently destroyed in a fire. Should both scenarios be treated equally, or should a distinction between these two losses be made? The answer rests with public policy makers who create tax law, where the answer can range from no capital loss deduction for anything to almost everything. The concern addressed next is that if the tax burden for the wealthy is disproportionately reduced, the middle class has a much greater tax burden, as the poor contribute little to tax revenue. Therefore, to justify a capital loss deduction, it is prudent to make an analogy with government-run health care, which shares an equivalent concept of large-scale group insurance.

Capital loss tax deduction is similar to an insurance program managed by the government. Specifically, all household incomes are being taxed, but the government only aids households suffering capital losses. A greater capital loss begets more government aid. The practice of spreading investment risk across the entire population to cover only households that made poor investments is like a health insurance program. That is, sick and healthy individuals are taxed, but the government only aids those suffering sickness. The greater the sickness begets more government aid. Again, aid only goes to a subpopulation to keep people functional and productive, which is beneficial to society as a whole. Although only a subpopulation will benefit from the insurance, a priori it is unknown who will use it.

The arguments against universal health care (lack of resources, highly skewed redistribution of income and poor government management) amplify against the rationale for capital loss tax deductions. The most troubling aspect is that only households with the highest income are predisposed to benefit. Thus, it is not self-evident that capital loss deductions should be included in a tax system. Nevertheless, creating opportunities that ensure the well-being of society must be the responsibility of government. When viewed as insurance, policy makers need only debate the scope of coverage. From this point of view, there is no universal answer for the scope of capital loss tax deduction or free health care services, since a weak economy cannot support the same level of coverage as a strong economy. As such, public policy debates will ultimately affect government budgets, tax rates and poverty line. The proposed tax system is designed to support the outcome of these debates within the constraints inherent in the tax system.

Since the capital loss deduction benefits society as a growth mechanism, it is included in the victory tax system to ensure generality. Nevertheless, since only a subset of households reaps the benefits, it is prudent to limit this redistribution of wealth to prevent a higher tax burden on households with much lower income. This limitation is similar to a maximum coverage limit in an insurance policy. Note that government transfer to the poor is limited by the poverty line, and a limit to the maximum itemized deduction was also introduced. In the same spirit, a cap on capital loss deductions is set by not counting capital losses that exceed capital gains within a given year. From a consistency point of view, paying tax on income must be over the same time period regardless of the income type or income level of a household. To roll over capital losses to future years, the same time period must apply to all income types. A tax system in which taxes are due annually seems reasonable, compared to alternatives such as every four months or every four years. For the prototype tax system constructed and demonstrated in this paper, capital losses are limited to one-year windows, which correspond to taxes collected annually. Although there is a maximum deduction for capital losses per year, no lifetime limit for capital losses is set. Likewise, there are annual limits, but no lifetime limit to government transfer or itemize deductions.

The definition of net income within the victory tax system is given as:

where

E defines earnings from employment,

defines capital income gained, and

defines capital income lost. Note that

includes all types of income that are not earnings from employment or government transfers. Upon inspection of (

3) within a given year, the government will maximally allow a household to deduct as much capital loss as gained. The amount of risk assumed is therefore determined by the skill of the investor. If an investor incurs more capital loss in a given year than capital gains, the government will not allow this excess loss to be deducted on the grounds that the investor creates too much risk for society to absorb. This restriction strengthens a free market: investors will exercise prudent judgments to ensure that gains are greater than losses when government assistance is limited. In practice, the tax system encourages investors to focus on fundamentals and long-term investments, spreading losses over multiple years. Placing annual limits on capital loss deductions (in fact all types of tax deductions) minimizes government dependency.

2.1.5. Tax Deductions Cannot Be Applied on Government Transfer

This principle is self-evident, because income from government transfers is at the expense of all taxpayers who make a productive contribution to society through earnings and/or capital gains. Note that allowing deductions on government transfer would amplify government assistance. This guideline minimizes government dependency.

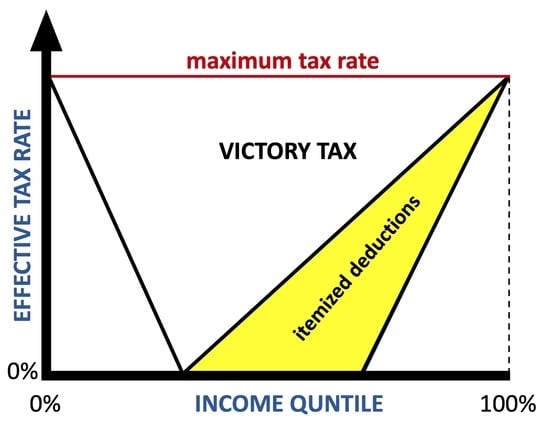

2.1.6. Unique Property of the Victory Tax System

To emphasize the unique properties of the victory tax system compared to other basic income guarantee tax systems, an important consequence follows when the first, third and fifth principles are combined. Since government transfer income is taxed, but deductions cannot be applied to this part of household income, a regressive ETR emerges as a function of income percentile for the poor. The regressive ETR enables low-income households receiving government aid to become self-reliant and achieve higher income levels without a welfare trap (the analog to a nucleation barrier). The formation of a low-income regressive ETR will become clear in the results section.

2.2. Mathematical Framework

The five principles examined above are now considered axioms to construct the general mathematical framework of the victory tax system. Relevant variables for a household to calculate tax liability are described in

Table 1 for convenient reference.

In addition to (

3) defining net income, the victory tax formulas are given as:

The variables {

E,

,

} quantify income characteristics of a household. Notice that the net income of a household can never be negative. The maximum income for a household eligible for government transfer is determined by the basic deduction,

. The word “eligible” underscores the restriction that households with incomes above

cannot receive government transfer. Otherwise,

defined in (

4) covers the income deficiency of a low-income household in order to put it on the poverty line. The parameters {

,

,

} define the maximum limits on allowed deductions. After the total tax deduction is determined from (

5), the taxable income is calculated by (

6). The victory tax rate,

, multiplies the taxable income of a household to obtain tax liability (

7). The after-tax income is calculated from (

8), which adds government transfer to net income minus paid tax. The

ETR is defined in (

9) as tax paid divided by the total income. Since no deductions can be applied to government transfer, it works out that

when

. Although counterintuitive, the poorest households pay the highest effective tax rate among the entire population.

Within the victory tax system,

, depends on the target tax revenue,

, deduced from projected budget needs for the next year set by policy makers. In addition,

, should be proportional to the poverty line,

which is the income required to maintain a minimum living cost. Reflecting the state of the economy,

will change annually to ensure that the least possible after-tax income,

, corresponds to

. From Equations (

3) and (

4) a household with

will have a taxable income equal to

from government transfer, and after-tax income will be given by

. This shows the insightful relationship that

, which indicates that as

increases, the basic tax deduction increases at a higher rate. When public policy makers propose to increase

for building infrastructure or defense,

will automatically increase even if the poverty line remains constant.

The two parameters {

,

} determine the shape of the

ETR. In practice,

and

will be functions of the number of dependents in a household, denoted as

d. For simplicity,

is considered independent of

d. Although

can be set with considerable latitude through tabulation, a sound approach is to set

proportional to

. By assuming

, the parameterization details for

as a function of dependents are inherited from

. For the US, the poverty line for a household with a certain number of dependents is publicly available in tables [

23]. More generally, an objective economic measure will be used to define

. Although not considered here to keep the analyses clear, the poverty line will generally depend on location (region within a country), since all regions do not have the same cost of living.

Parameters for the victory tax system are explored in

Section 3. It is found that when

and

, a V-shape signature emerges for the

ETR as a function of income percentile, with

marking the bottom of the V. Importantly, (

5) determines the allowed tax deduction after taking into account basic and itemized deductions and maximum percent of

. Since itemized plus basic deductions increase total deduction, the term

that appears in (

5) is needed to enforce consistency. In particular, when

is set below

as an independent variable, the basic deduction is still offered, but itemized deductions are no longer allowed. However,

can reduce the maximum allowed deduction below

without inconsistency, because

is a competing restriction on tax deductions. Note that a flat tax corresponds to the limit

, where

ETR is constant, independent of income percentile.

As

gradually changes from 1 to 0, the V-shape morphs into a U-shape as the “U” becomes shallower, with the minimum

ETR increasing as

decreases. These shape changes create an elastic tax system [

24]. At

a flat tax emerges as a special case of a victory tax system, where

sets the threshold income in which government transfer is no longer received. A prototypical victory tax system considered in this work is defined by:

and

, where

r is the coefficient of variation in net income over the population. Specifically,

r is the ratio of the standard deviation in

to the mean

, which serves as a convenient objective measure of the economy. The application of objective measures updates

and

r each year, allowing the victory tax system to respond dynamically to changes in the free market and public policy.

The basic deduction is determined in the prototypical victory tax once parameter

k is specified together with the poverty line,

. By combining equations of the victory tax system, the tax liability of a household with

d dependents is given as

from Equation (

7), and its taxable income is expressed as:

where

x is the net income (replacing

for simpler mathematical notation) and the subscript

d denotes the fact that the poverty line depends on the number of dependents in a household. Equation (

10) is the result of substituting all the relevant variables described above in the arguments of Equation (

6). Note that

depends on

, which is the dependent variable to be determined. In addition,

where

is the total taxable income over the population, and

is the total tax revenue to be collected over the population. To calculate

, we must have

, which is given by the net sum of

over all households in the population. However, to calculate

, we must have

because

depends on

. Despite this circular dependence, it is straightforward to numerically solve for

iteratively. Uncertainties in

will primarily arise from estimates in

that will lead to surpluses or deficits at the end of a tax year when government spending deviates from budgeted allocations. These calculations are not technically difficult. The tax agency will have all income data from previous years, and

, based on the latest tax records, can be calculated with all details from the tax code. However, the aim of this paper is to analyze the general characteristics of the victory tax system, rather than focus on nuanced details.

For clarity and without loss of generality, the characteristics of the victory tax system are analyzed using an average household size and with the subscript

d suppressed. This allows

to be expressed through the simple function

, which gives the income distribution over households of the average size. Defining

to be the number of such households, and

the probability density function quantifying how income is distributed over these households,

. Assuming all households will take the maximum itemized deduction based on (Equation (

10)), a lower-bound estimate for

is obtained. With

from the simplifying assumptions, the total taxable income of the entire population is given by: