2. Results and Discussion

The key boronic acid, hydroxyterphenylboronic acid

1, was easily prepared according to the route shown in

Scheme 2. Compound

2 [

24] was treated with BuLi in Et

2O at −78 °C, and then THF was added. This sequential use of the two solvents (Et

2O and THF) ensured satisfactory conversion to the dilithiated compound, without the formation of a significant amount of the byproduct protonated at the lithiated carbon [

25]. This was possible because the Li–Br exchange occurred only after the addition of THF [

26]. The dilithiated compound was then boronated to give

1 in good yield (72%).

Scheme 2.

Preparation of hydroxyterphenylboronic acid 1.

Scheme 2.

Preparation of hydroxyterphenylboronic acid 1.

Boronic acid

1 was first applied to the synthesis of

o,

o,

p-oligophenylenes, composed of benzene rings connected in the order of

ortho,

ortho, and then

para. These were envisioned to make up a new structural motif of folding oligophenylenes [

27]. While

o,

o,

p-oligophenylenes could be synthesized using our previous reported method [

27] involving the C–H arylation of bipheny-2-ols as the key step, the present method using

1 would be more efficient for synthesis of longer oligomers.

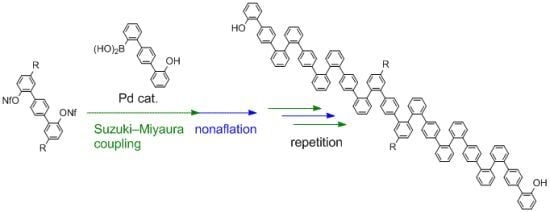

Thus, we started with compound

3 (

Scheme 3), with dodecanoyl groups introduced in order to increase the solubility of the oligomers in organic solvents. While the triflyl group (Tf, –SO

2CF

3) was used to activate hydroxy groups in the previous work (

Scheme 1a), we decided to use the nonaflyl group (Nf, –SO

2C

4F

9) [

27,

28], as this is more stable against O–SO

2 bond cleavage [

29,

30] and can be prepared with NfF, which is usually less expensive than the commonly used triflating agent, Tf

2O.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of o,o,p-oligophenylenes.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of o,o,p-oligophenylenes.

Nonaflation of

3 gave bisnonaflate

4, which was then subjected to Suzuki-Miyaura coupling with

1 in the presence of a Pd/SPhos catalyst [

31]. Double Suzuki-Miyaura coupling introduced two terphenyl units to give

5 in good yield (72%). Repetition of the nonaflation/Suzuki-Miyaura-coupling sequence twice afforded symmetric

o,

o,

p-oligophenylene

9. It should be emphasized that only six steps were required to synthesize 21-mer oligophenylene

9 from

3. Although these

o,

o,

p-oligophenylenes showed complicated

1H- and

13C-NMR spectra because of the existence of rotamers, even at 100 °C, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis verified the identities and the purities of the oligomers.

We next turned our attention to combining the previous and present strategies (

Scheme 1a,b) to facilitate synthesis of another type of oligophenylenes.

o,p-Oligophenylenes, which are used as precursors in bottom-up synthesis of graphene nanoribbons [

32], were selected as the model target [

33] in order to demonstrate the feasibility of the combined strategy.

The synthesis commenced using 1,4-dibromobenzene, which was subjected to Suzuki-Miyaura coupling with

1 (

Scheme 4). Although the reaction was slow at rt, raising the temperature to 70 °C resulted in a good yield of 7-mer

10 (72%). After nonaflation, Suzuki-Miyaura-coupling with 4-hydroxyphenylboronic acid was conducted, affording 9-mer

12. While nonaflation of

12 in CH

3CN resulted in a low yield due to the low solubility of

12 in this particular solvent, use of a mixed solvent (CH

3CN/CH

2Cl

2) improved the yield to 77%. For the final Suzuki-Miyaura-coupling step, it was necessary to change the reaction conditions, as the low solubility of

13 in THF/H

2O hampered the reaction under the previous employed conditions. Finally, we found that the use of K

3PO

4∙nH

2O in toluene gave 15-mer

14 in a modest yield (43%). In contrast to the

o,

o,

p-oligophenylenes, rotamers were not observed in the NMR spectra of the

o,

p-oligophenylenes at room temperature. The synthesis shown in

Scheme 4 clearly demonstrates that

o,

p-oligophenylenes with a specific chain length can be easily synthesized through this strategy.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of o,p-oligophenylenes.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of o,p-oligophenylenes.

Crystals of 9-mer

12 suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained by recrystallization from CH

3CN, with the resulting structure shown in

Figure 1 [

34]. This is the first X-ray structure of

o,

p-oligophenylenes that has been obtained. The 9-mer can be seen adopt an S-shaped, centrosymmetric conformation in which the inversion center is located at the central benzene ring. Both of the hydroxy groups were observed to form hydrogen bonds with CH

3CN molecules.

Figure 1.

ORTEP representation (50% ellipsoid probability) of the X-ray structure of 12∙2CH3CN. Only one CH3CN molecule is shown. Left, front view; Right, side view.

Figure 1.

ORTEP representation (50% ellipsoid probability) of the X-ray structure of 12∙2CH3CN. Only one CH3CN molecule is shown. Left, front view; Right, side view.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General

All reactions were performed under argon atmosphere. Reactions were monitored by TLC on Merck (Tokyo, Japan) silica gel 60 F254 plates visualized by UV lump at 254 nm. Column chromatography was performed on Merck (Tokyo, Japan) silica gel 60 and preparative TLC was performed on Merck (Tokyo, Japan) silica gel 60 F254 0.5 mm plates. NMR spectra were measured on a JEOL (Akishima, Japan) AL-400 NMR spectrometer (400 MHz for 1H spectra and 100 MHz for 13C spectra) and a JEOL Akishima, Japan) ECA-500 NMR spectrometer (500 MHz for 1H spectra and 125 MHz for 13C spectra). For 1H NMR, tetramethylsilane (TMS) (δ = 0) in CDCl3 served as an internal standard. For 13C NMR, CDCl3 (δ = 77.0) served as an internal standard. Infrared spectra were measured on a SHIMADZU (Kyoto, Japan) IR Prestige-21 spectrometer (ATR). High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were measured on a JEOL (Akishima, Japan) JMS-T100TD time-of-flight mass spectrometer (DART), Bruker (Billerica, MA, USA) micrOTOF mass spectrometer (ESI), or Bruker (Billerica, MA, USA) Ultraflex TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (MALDI). Melting points were measured using MPA 100 OptiMelt (Stanford Research Systems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and uncorrected. X-ray analysis was made on a Rigaku (Tokyo, Japan) AFC7R diffractometer using graphite monochromated Mo-Kα radiation and a rotating anode generator.

Anhydrous solvents (except for acetonitrile) were purchased from Kanto Chemical (Tokyo, Japan) and used without further purification. Acetonitrile was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan) and distilled from CaH2 under argon. All other chemicals were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Kanto Chemical, Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan), and Aldrich (Milwaukee, US) and used without further purification.

3.2. 2''-Hydroxy-[1,1':4',1''-terphenyl]-2-yl) Boronic Acid (1)

n-BuLi (1.59 M in hexane, 12.6 mL, 20.0 mmol) was added over the course of 3 min to a solution of 2 (3.25 g, 10.0 mmol) in Et2O (20.0 mL) at −78 °C under Ar. After 10 min, THF (20.0 mL) was added. After a further 10 min, triisopropyl borate (2.7 mL, 12.0 mmol) was added over the course of 5 min, and the mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 3 h. Aqueous HCl (1 M, 50 mL) was added. The THF was then removed in vacuo. The mixture was subsequently extracted with Et2O, and the organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by recrystallization (EtOAc/hexane/H2O = 10:4:1) to give 1 (2.12 g, 72%) as a white solid. mp. 126.6–129.6 °C; IR (ATR) (cm−1) 3500, 1473, 1332, 752; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, acetone-d6 with one drop of D2O): δ 6.93 (1H, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.03 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.18 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.31–7.37 (2H, m), 7.41–7.44 (2H, m), 7.50 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.65 (3H, m); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, acetone-d6 with one drop of D2O): δ 116.8, 120.6, 126.8, 129.3, 128.5, 128.9, 129.2, 129.6, 129.8, 131.1, 133.8, 136.3, 138.2, 142.3, 145.9, 155.0; Anal. calcd for C18H15BO3: C, 74.52; H, 5.21, found: C, 74.53; H, 5.27.

3.3. 3-mer (OH) (3)

[1,1':4',1''-Terphenyl]-2,2''-diol [

35] (78.7 mg, 0.300 mmol) and

n-dodecanoyl chloride (136 mg, 0.622 mmol) were dissolved in TfOH [

36] (0.6 mL) at rt, and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at the same temperature. After the reaction was complete, H

2O (5.0 mL) was added. The mixture was then extracted with CH

2Cl

2, and the organic layer was washed with saturated NaHCO

3 and brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and concentrated

in vacuo. The residue was purified by recrystallization from methanol to give

3 (160 mg, 85%) as a white solid. mp. 119.4–121.5 °C; IR (ATR) (cm

−1) 3331, 1467, 1278, 1193, 844, 667;

1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3): δ 0.87 (6H, t,

J = 6.8 Hz), 1.26 (32H, bs), 1.74 (4H, quint,

J = 6.8 Hz), 2.94 (4H, t,

J = 7.2 Hz), 6.56 (2H, s), 7.06 (2H, d,

J = 8.4 Hz), 7.62 (4H, s), 7.92 (2H, dd,

J = 8.8, 2.0 Hz), 7.96 (2H, d,

J = 2.0 Hz);

13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl

3): δ 14.0, 22.6, 24.8, 29.3, 29.45, 29.49, 29.58, 29.6, 31.9, 38.4, 116.2, 127.9, 129.8, 130.0, 130.4, 131.2, 136.4, 157.5, 200.2 (one carbon overlapped.); HRMS (ESI):

m/

z calcd for C

42H

57O

4 ([M − H]

−) 625.4262; found: 625.4275.

3.4. 3-mer (ONf) (4)

Perfluorobutanesulfonyl fluoride (0.182 mL, 1.02 mmol) was added over 1 min to a solution of 21 (0.160 g, 0.255 mmol) and Et3N (0.28 mL, 2.04 mmol) in MeCN (0.85 mL) at 0 °C, and the mixture was stirred for 1 min at the same temperature. The reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature and then stirred for a further 4 h. After the reaction was complete, aqueous HCl (1 M, 5.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, and the organic layer was washed with H2O and brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified using silica gel chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 4:1) to give 4 (0.250 g, 82%) as a yellow oil. IR (ATR) (cm−1) 1695, 1427, 1236, 887; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.86–0.90 (6H, m), 1.28–1.38 (32H, brs), 1.76–1.79 (4H, m), 2.98–3.02 (4H, m), 7.52–7.70 (6H, m), 8.06 (2H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.8 Hz), 8.13 (2H, d, J = 2.0 Hz); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.7, 24.1, 29.26, 29.32, 29.45, 29.48, 29.6, 31.9, 38.8, 122.4, 129.1, 129.7, 131.9, 135.2, 135.5, 137.0, 149.6, 198.6 (one carbon signal overlapped). Nonaflyl carbons were not observed because of the low signal intensities; HRMS (dart): m/z calcd for C50H57F18O6S2 ([M + H]+) 1191.3202; found: 1191.3194.

3.5. 9-mer (OH) (5)

Nonaflate 4 (1.23 g, 1.04 mmol), 1 (0.699 g, 2.41 mmol), KF (0.451 g, 7.76 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (23.2 mg, 0.104 mmol), and SPhos (51.0 mg, 0.124 mmol) were placed in a sealable tube, which was then evacuated and backfilled with Ar. A mixture of THF/H2O (4:1, 1.0 mL) was then added. The tube was sealed, and the mixture was stirred at 50 °C for 17 h. After the reaction was complete, H2O (5.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, and the organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified using silica gel chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 1:2) to give 5 (0.807 g, 72%) as a white solid. mp. 130.1–134.3 °C; IR (ATR) (cm−1) 3516, 1685, 1450, 1267, 827, 746; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.86 (6H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.24 (32H, brs), 1.70–1.77 (4H, m), 2.95–3.00 (4H, m), 6.02 (0.5H, s), 6.31 (4.5H, s), 6.53 (3H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.57 (1H, s), 6.73 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz), 6.87–6.97 (4H, m), 7.08–7.39 (16.5H, m), 7.52 (1.5H, d, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.85 (2.5H, s), 7.96 (1.5H, d, J = 8.0 Hz) (mixture of rotamers); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.7, 24.3, 29.31, 29.36, 29.48, 29.5, 29.6, 31.9, 38.7, 115.8, 116.0, 120.7, 120.8, 126.9, 127.0, 127.5, 127.58, 127.6, 127.7, 128.16, 128.2, 128.3, 128.5, 128.9, 129.0, 129.5, 129.7, 129.86, 129.97, 130.0, 130.1, 131.4, 131.5, 132.2, 134.9, 135.1, 135.4, 136.1, 136.2, 138.3, 138.6, 138.8, 139.0, 139.5, 139.9, 140.0, 140.1, 140.8, 140.9, 152.4, 152.6, 200.7 (mixture of rotamers); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C78H81O4 ([M − H]−) 1081.6140; found: 1081.6102.

3.6. 9-mer (ONf) (6)

Perfluorobutanesulfonyl fluoride (0.70 mL, 3.86 mmol) was added over 1 min to a solution of 5 (1.05 g, 0.965 mmol) and Et3N (1.10 mL, 7.72 mmol) in MeCN (3.2 mL) at room temperature, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h at the same temperature. After the reaction was complete, aqueous HCl (1 M, 5.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, and the organic layer was washed with H2O and brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified using silica gel chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 3:1) to give 6 (1.46 g, 92%) as a colorless oil. IR (ATR) (cm−1) 1685, 1236, 1142, 835, 765; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.87 (6H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 1.25–1.32 (32H, m), 1.68–1.73 (4H, m), 2.92–2.98 (4H, m), 6.44 (2.6H, s), 6.648 (2.6H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 6.649 (1.4H, s), 6.80 (1.4H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.09 (2.6H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.12 (1.4H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.29–7.51 (18H, m), 7.70 (1.3H, s), 7.83 (0.7H, s), 7.86 (0.7H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.95 (1.3H, dd, J = 8.0, 1.5 Hz) (mixture of rotamers); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.8, 24.3, 24.4, 29.4, 29.60, 29.63, 29.7, 32.0, 38.6, 121.9, 126.6, 127.5, 128.1, 128.2, 128.56, 128.63, 128.7, 128.88, 128.9, 129.0, 129.7, 129.9, 130.1, 130.2, 130.3, 131.2, 131.5, 131.9, 132.1, 133.9, 135.7, 136.2, 136.3, 138.9, 139.2, 139.5, 140.35, 140.43, 140.8, 140.9, 141.2, 141.4, 141.47, 144.54, 147.3, 200.2, 200.3 (mixture of rotamers) (Nonaflyl carbons were not observed because of the low signal intensities) HRMS (MALDI, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as the matrix): m/z calcd for C86H80F18O6S2 ([M + H]+) 1646.5007; found: 1647.5108.

3.7. 15-mer (OH) (7)

Nonaflate 6 (0.972 g, 0.590 mmol), 1 (0.514 g, 1.77 mmol), KF (0.257 g, 4.43 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (13.2 mg, 0.0590 mmol), and SPhos (29.1 mg, 0.0708 mmol) were placed in a flask, which was then evacuated and backfilled with Ar. A mixture of THF/H2O (4:1, 0.59 mL) was then added. The tube was sealed, and the mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 17 h. After the reaction was complete, H2O (5.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, and the organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified using silica gel chromatography (hexane/EtOAc = 10:1) to give 7 (0.711 g, 78%) as a yellow solid. mp. 109.5–115.0 °C; IR (ATR) (cm−1) 3529, 1678, 1467, 1269, 829, 748; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.87 (6H, m), 1.24 (32H, brs), 1.71 (4H, brs), 2.95 (4H, brs), 5.50–6.70 (18H, m), 6.92–7.97 (42H, m) (mixture of rotamers); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.7, 24.2, 24.29, 29.31, 29.35, 29.38, 29.48, 29.51, 29.6, 31.9, 38.7, 115.7, 115.8, 120.5, 120.6, 120.7, 126.9, 127.3, 127.5, 127.7, 127.9, 128.0, 128.3, 128.4, 128.6, 128.7, 128.9, 129.0, 129.6, 129.8, 129.9, 131.4, 131.6, 134.8, 136.0, 138.26, 138.30, 138.4, 138.5, 138.9, 139.0, 139.7, 140.0, 140.1, 140.2, 140.3, 140.8, 141.6, 152.7, 152.8, 200.4 (mixture of rotamers); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C114H105O4 ([M − H]−) 1537.8018; found: 1537.8010.

3.8. 15-mer (ONf) (8)

Perfluorobutanesulfonyl fluoride (0.11 mL, 0.604 mmol) was added over 1 min to a solution of 7 (0.233 g, 0.151 mmol) and Et3N (0.17 mL, 1.21 mmol) in MeCN (0.5 mL) at room temperature, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h at the same temperature. After the reaction was complete, aqueous HCl (1 M, 10.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, and the organic layer was washed with H2O and brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified using silica gel chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 4:1) to give 8 (0.146 g, 46%) as a colorless oil. IR (ATR) (cm−1) 1685, 1423, 1236, 889, 732; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.85–0.88 (6H, m), 1.25 (32H, brs), 1.71 (4H, brs), 2.95 (4H, brs), 5.65–6.71 (18H, m), 6.91–7.95 (42H, m) (mixture of rotamers); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.7, 24.2, 24.3, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5, 29.6, 31.9, 38.6, 118.5, 121.9, 126.4, 126.8, 127.1, 127.4, 127.9, 128.2, 128.5, 128.6, 128.75, 128.83, 128.9, 129.1, 129.4, 129.8, 129.9, 130.0, 130.2, 130.7, 131.3, 131.7, 131.8, 132.1, 133.4, 133.5, 135.5, 135.6, 136.1, 138.5, 138.6, 139.1, 139.3, 139.6, 140.1, 140.3, 141.0, 141.1, 141.6, 144.9, 145.2, 147.0, 199.7, 200.2 (mixture of rotamers) (Nonaflyl carbons were not observed because of the low signal intensities); HRMS (MALDI, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as a matrix): m/z calcd for C122H105F18O6S2 ([M + H]+) 2103.6958; found: 2103.7120.

3.9. 21-mer (OH) (9)

Nonaflate 8 (0.186 g, 0.088 mmol), 1 (76.9 mg, 0.264 mmol), KF (38.3 mg, 0.660 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (2.0 mg, 0.00880 mmol), and SPhos (4.3 mg, 0.0106 mmol) were placed in a flask, which was then evacuated and backfilled with Ar. A mixture of THF/H2O (4:1, 0.09 mL) was then added. The tube was sealed, and the mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 17 h. After the reaction was complete, H2O (5.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, and the organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified using silica gel chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 1:2) to give 9 (76.3 mg, 43%) as a white solid. mp. 135.3–138.9 °C; IR (ATR) (cm−1) 3537, 1678, 1467, 748; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.85–0.86 (6H, m), 1.24 (32H, bs), 1.49–1.72 (4H, m), 2.73–2.91 (4H, m), 5.35–5.60 (2H, m), 6.04–6.67 (23H, m), 6.83–8.00 (59H, m) (mixture of rotamers); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.7, 23.9, 24.2, 29.28, 29.33, 29.5, 29.6, 29.7, 31.9, 38.4, 38.6, 115.7, 120.7, 126.4, 126.8, 126.9, 127.1, 127.3, 127.4, 127.5, 127.6, 127.7, 127.96, 128.04, 128.2, 128.5, 128.6, 128.9, 129.0, 129.7, 130.0, 130.3, 130.7, 131.1, 131.3, 131.4, 134.4, 135.9, 138.37, 138.45, 138.6, 138.8, 138.9, 139.1, 139.3, 139.6, 139.8, 139.9, 140.0, 140.1, 140.2, 140.4, 140.9, 141.0, 141.4, 144.9, 152.5, 152.6, 151.7, 199.5, 200.1 (mixture of rotamers); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C150H129O4 ([M − H]−) 1993.9896; found: 1993.9873.

3.10. 7-mer (OH) (10)

4-Dibromobenzene (236.5 mg, 1.00 mmol), 1 (725.6 mg, 2.50 mmol), KF (437.2 mg, 7.53 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (22.7 mg, 0.101 mmol), and SPhos (49.7 mg, 0.121 mmol) were placed in a sealable tube, which was then evacuated and backfilled with Ar. A mixture of THF/H2O (4:1, 1.0 mL) was then added. The tube was sealed, and the mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 21 h. After the reaction was complete, H2O (10.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc, and the organic layer was washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by recrystallization (toluene) to give 10 (412.4 mg, 72%) as a white solid. mp. 255.6–257.5 °C; IR (ATR) (cm−1) 3003, 1711, 1358, 1221, 750; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 5.14 (2H, s), 6.93 (2H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 6.95 (2H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.07 (4H, s), 7.20–7.23 (2H, m), 7.26 (4H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.33 (4H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.41–7.46 (10H, m); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 115.9, 121.0, 127.7, 127.8, 128.5, 129.2, 129.6, 130.3, 130.6, 130.8, 130.8, 135.3, 139.8, 139.9, 140.3, 141.2, 152.5; HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C42H29O2 ([M − H]−) 565.2173; found: 565.2170.

3.11. 7-mer (ONf) (11)

Perfluorobutanesulfonyl fluoride (1.65 mL, 9.40 mmol) was added over 1 min to a solution of 10 (1.31 g, 2.31 mmol) and Et3N (2.6 mL, 18.7 mmol) in MeCN (7.9 mL) at room temperature, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h at the same temperature. After the reaction was complete, aqueous HCl (1 M, 20.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc, and the organic layer was washed with H2O and brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. MeOH was then added to the residue. After stirring, filtration gave 11 (1.65 g, 63%) as a white solid. mp. 198.5–199.8 °C; IR (ATR) (cm−1) 1429, 1202, 1140; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.03 (4H, s), 7.24 (4H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.31 (4H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.35–7.45 (16H, m); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 121.9, 127.4, 127.7, 128.6, 128.9, 129.7, 130.2, 130.5, 130.7, 132.0, 133.9, 135.9, 139.4, 139.9, 140.5, 141.9, 147.3; HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C50H28F18NaO6S2 ([M + Na]+) 1153.0932; found: 1153.0875.

3.12. 9-mer (OH) (12)

Nonaflate 11 (564 mg, 0.499 mmol), 4-hydroxyphenylboronic acid (173.6 mg, 1.26 mmol), KF (219.3 mg, 3.78 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (11.8 mg, 0.0526 mmol), and SPhos (25.1 mg, 0.0611 mmol) were placed in a sealable tube, which was then evacuated and backfilled with Ar. A mixture of THF/H2O (4:1, 1.0 mL) was then added. The tube was sealed, and the mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 23 h. H2O (10.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc, and the organic layer was washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified using silica gel chromatography (hexane/EtOAc = 4:1 to 2:1) to give 12 (222.2 mg, 62%) as a white solid. mp. 244.1–246.5 °C; IR (ATR) (cm−1) 3003, 1709, 1358, 1219, 1092, 903; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 3.82 (2H, s), 6.39 (4H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.85 (4H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.87 (4H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 6.93 (4H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 6.93 (4H, s), 7.32–7.52 (16H, m); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 114.9, 127.2, 127.4, 127.6, 127.7, 129.2, 129.6, 129.7, 130.4, 130.5, 130.6, 130.6, 131.0, 139.2, 139.4, 140.1, 140.3, 140.4, 140.5, 140.5, 154.1; HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C54H37O2 ([M − H]−) 717.2799; found: 717.2770.

3.13. 9-mer (ONf) (13)

Perfluorobutanesulfonyl fluoride (0.21 mL, 1.20 mmol) was added over 1 min to a solution of 12 (216.4 mg, 0.301 mmol) and Et3N (0.33 mL, 2.37 mmol) in MeCN/CH2Cl2 (1:1, 1.0 mL) at room temperature, and the mixture was stirred for 22 h at the same temperature. After the reaction was complete, aqueous HCl (1 M, 5.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc, and the organic layer was washed with H2O and brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. MeOH was then added to the residue. After stirring, filtration gave 13 (298.4 mg, 77%) as a white solid. mp. 204.4–205.8 °C; IR (ATR) (cm−1) 1713, 1429, 1358, 1221, 1138, 845; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 6.89 (4H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 6.94 (4H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 6.95 (4H, s), 7.01 (4H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.10 (4H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.33–7.43 (16H, m); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 120.8, 127.7, 127.7, 128.3, 129.3, 129.5, 129.7, 130.4, 130.5, 130.5, 130.6, 131.6, 138.6, 139.1, 139.8, 139.9, 140.1, 140.2, 140.4, 142.1, 148.6; HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C62H36ClF18O6S2 ([M + Cl]−) 1317.1360; found: 1317.1356.

3.14. 15-mer (OH) (14)

Nonaflate 13 (320.5 mg, 0.250 mmol), 1 (218.6 mg, 0.753 mmol), K3PO4∙nH2O (502.2 mg), Pd(OAc)2 (5.6 mg, 0.0249 mmol), and SPhos (20.5 mg, 0.0499 mmol) were placed in a sealable tube, which was then evacuated and backfilled with Ar. Toluene (2.0 mL) was then added. The tube was sealed, and the mixture was stirred at 120 °C for 24 h. After the reaction was complete, H2O (10.0 mL) was added. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc and CHCl3, and the organic layer was washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified using silica gel chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 1:1 to 1:2) to give 14 (126.3 mg, 43%) as a white solid. mp. 280.2–282.0 °C; IR (ATR) (cm−1) 3003, 1709, 1358, 1219, 1092, 903; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 5.03 (2H, s), 6.88 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 6.90 (4H, s), 6.91 (8H, s), 6.94 (8H, s), 7.11 (2H, dd, J = 7.8, 2.0 Hz), 7.16–7.19 (6H, m), 7.21–7.24 (4H, m), 7.27–7.41 (26H, m); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 115.9, 120.9, 127.5, 127.5, 127.6, 127.8, 128.5, 129.1, 129.4, 129.5, 129.6, 130.3, 130.5, 130.6, 130.7, 130.8, 135.2, 139.6, 139.7, 139.8, 139.9, 140.2, 140.3, 140.4, 141.1, 152.5, 153.2; HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C90H61O2 ([M − H]−) 1173.4677; found: 1173.4636.