Synthesis and Antiproliferative Effects of Amino-Modified Perillyl Alcohol Derivatives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

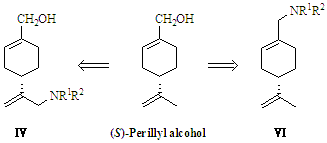

2.1. Synthesis of (S)-Perillyl Alcohol Derivatives

2.2. Antiproliferative Effects in Tumor Cells

| Compound | IC50 (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | A375-S2 | HT1080 | |

| I | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

| IV1 | 437.76 | 309.61 | 556.38 |

| IV2 | 948.35 | 501.32 | >1000 |

| IV3 | 405.07 | 287.79 | 59.91 |

| IV4 | 403.22 | 110.07 | 386.35 |

| IV5 | 384.63 | 395.10 | 340.43 |

| IV6 | 735.29 | >1000 | >1000 |

| IV7 | 417.03 | 436.77 | 73.11 |

| VI1 | 270.11 | 359.23 | 426.01 |

| VI2 | 427.52 | 463.80 | 409.16 |

| VI3 | 393.69 | 472.75 | 483.37 |

| VI4 | 619.11 | 90.05 | 761.80 |

| VI5 | 53.80 | 53.80 | 56.17 |

| VI6 | 432.46 | 424.74 | 496.41 |

| VI7 | 69.50 | 72.77 | 69.37 |

2.3. Apoptosis in A549 Cells Induced by VI5

3. Experimental

3.1. General Information

3.2. (S)-(4-(Prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohex-1-enyl)methanol (I)

: −86° (c = 1, MeOH), in lit. [20],

: −86° (c = 1, MeOH), in lit. [20],  : −88° (c = 1, MeOH). 1H-NMR δ: 5.70 (1H, br s, CH), 4.73, 4.71 (2H, s, s, CH2), 4.02–3.97 (2H, m, OCH2), 2.18–2.05 (4H, m), 2.00–1.93 (1H, m), 1.88–1.84 (1H, m), 1.74 (3H, s, CH3), 1.61–1.42 (1H, m). 13C-NMR(75 MHz) δ: 149.8, 137.3, 122.5, 108.7, 67.3, 41.2, 30.4, 27.5, 26.1, 20.8 [21].

: −88° (c = 1, MeOH). 1H-NMR δ: 5.70 (1H, br s, CH), 4.73, 4.71 (2H, s, s, CH2), 4.02–3.97 (2H, m, OCH2), 2.18–2.05 (4H, m), 2.00–1.93 (1H, m), 1.88–1.84 (1H, m), 1.74 (3H, s, CH3), 1.61–1.42 (1H, m). 13C-NMR(75 MHz) δ: 149.8, 137.3, 122.5, 108.7, 67.3, 41.2, 30.4, 27.5, 26.1, 20.8 [21].3.3. (S)-(4-(Prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohex-1-enyl)methyl Acetate (II)

3.4. (S)-(4-(1-Chloroprop-2-en-2-yl)cyclohex-1-enyl)methyl Acetate (III)

3.5. (S)-1-Chloromethyl-4-(prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohex-1-ene (V)

3.6. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Target Compounds IV1–IV7

3.7. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Target Compounds VI1–VI7

3.8. Biological Activity

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newman, D.J. Natural products as leads to potential drugs: An old process or the new hope for drug discovery? J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 2589–2599. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell, P.L.; Chang, R.R.; Ren, Z.; Elson, C.E.; Gould, M.N. Selective inhibition of isoprenylation of 21–26-kDa proteins by the anticarcinogen d-limonene and its metabolites. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 17679–17685. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell, P.L.; Ren, Z.; Lin, S.; Vedejs, E.; Gould, M.N. Structure-activity relationships among monoterpene inhibitors of protein isoprenylation and cell proliferation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994, 47, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Gelb, M.H.; Tamanoi, F.; Yokoyama, K.; Ghomashchi, F.; Esson, K.; Gould, M.N. The inhibition of protein prenyltransferases by oxygenated metabolites of limonene and perillyl alcohol. Cancer Lett. 1995, 91, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Z.; Elson, C.E.; Gould, M.N. Inhibition of type I and type II geranylgeranyl-protein transferases by the monoterpene perillyl alcohol in NIH3T3 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1997, 54, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Gould, M.N. Induction of cytostasis in mammary carcinoma cells treated with the anticancer agent perillyl alcohol. Carcinogenesis 2002, 23, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Yeruva, L.; Pierre, K.J.; Elegbede, A.; Wang, R.C.; Carper, S.W. Perillyl alcohol and perillic acid induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in non small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2007, 257, 216–216. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Oettel, K.; Bailey, H.H.; van Ummersen, L.; Tutsch, K.; Staab, M.J.; Horvath, D.; Alberti, D.; Arzoomanian, R.; Rezazadeh, H.; et al. Phase II trial of perillyl alcohol (NSC 641066) administered daily in patients with metastatic androgen independent prostate cancer. Investig. New Drugs 2003, 21, 367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, H.H.; Attia, S.; Love, R.R.; Fass, T.; Chappell, R.; Tutsch, K.; Harris, L.; Jumonville, A.; Hansen, R.; Shapiro, G.R.; et al. Phase II trial of daily oral perillyl alcohol (NSC 641066) in treatment-refractory metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2008, 62, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, D.M. Ras farnesyltransferase: A new therapeutic target. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 2971–2990. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Levin, D.; Pupalli, S. Pharmaceutical compositions comprising POH derivatives. WO2012027693, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eummer, J.T.; Gibbs, B.S.; Zahn, T.J.; Sebolt-Leopold, J.S.; Gibbs, R.A. Novel limonene phosphonate and farnesyl diphosphate analogues: Design, synthesis, and evaluation as potential protein-farnesyl transferase inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999, 7, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.C.; Mahalingam, S.M.; Panda, L.; Wang, B.; Campbell, P.D.; Evans, T. Design and synthesis of potential new apoptosis agents: Hybrid compounds containing perillyl alcohol and new constrained retinoids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 1462–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthakis, E.; Magkouta, S.; Loutrari, H.; Stamatis, H.; Roussos, C.; Kolisis, F.N. Enzymatic synthesis of perillyl alcohol derivatives and investigation of their antiproliferative activity. Biocatal. Biotransfor. 2009, 27, 170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmannsberger, C.; Mross, K.; Jakob, A.; Kanz, L.; Bokemeyer, C. Topotecan—A novel topoisome rase inhibitor: Pharmacology and clinical experience. Oncology 1999, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sandier, A.; van Oosterom, A.T. Irinotecan in cancer of the lung and cervix. Anti-Cancer Drugs 1999, 10, S13–S17. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Tao, S.; Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, M.; Chen, D.; Jing, Y.; Dong, J. The synthesis and anti-proliferative effects of â-elemene derivatives with mTOR inhibition activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 5351–5356. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, M.; Jing, Y.; Dong, J. The synthesis of L-carvone and limonene derivatives with increased antiproliferative effect and activation of ERK pathway in prostate cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 6539–6547. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, S.; Plesca, D.; Almasan, A. Caspase-3 activation is a critical determinant of genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008, 414, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Karlson, J.; Borg-Karlson, A.-K.; Unelius, R.; Shoshan, M.C.; Wilking, N.; Ringborg, U.; Linder, S. Inhibition of tumor cell growth by monoterpenes in vitro: Evidence of a Ras-independent mechanism of action. Anti-Cancer Drugs 1996, 7, 422–429. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino, M.G.; Lacerda Júnior, V.; Invernize, P.R.; Carlos da Silva Filho, L.; José da Silva, G.V. Opening of epoxide rings catalyzed by niobium pentachloride. Synth. Commun. 2007, 37, 3529–3539. [Google Scholar]

- Sahli, Z.; Sundararaju, B.; Achard, M.; Bruneau, C. Selective carbon–carbon bond formation: Terpenylations of amines involving hydrogen transfers. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 775–779. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Li, L.; Chen, S.; Yu, Y.; Qi, M.; Tashiro, S.I.; Onodera, S.; Ikejima, T. Silibinin induced-autophagic and apoptotic death is associated with an increase in reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in HeLa cells. Free Radic. Res. 2011, 45, 1307–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, M.; Yao, G.; Fan, S.; Cheng, W.; Tashiro, S.I.; Onodera, S.; Ikejima, T. Pseudolaric acid B induces mitotic catastrophe followed by apoptotic cell death in murine fibrosarcoma L929 cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 683, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

© 2014 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Hui, Z.; Zhang, M.; Cong, L.; Xia, M.; Dong, J. Synthesis and Antiproliferative Effects of Amino-Modified Perillyl Alcohol Derivatives. Molecules 2014, 19, 6671-6682. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19056671

Hui Z, Zhang M, Cong L, Xia M, Dong J. Synthesis and Antiproliferative Effects of Amino-Modified Perillyl Alcohol Derivatives. Molecules. 2014; 19(5):6671-6682. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19056671

Chicago/Turabian StyleHui, Zi, Meihui Zhang, Lin Cong, Mingyu Xia, and Jinhua Dong. 2014. "Synthesis and Antiproliferative Effects of Amino-Modified Perillyl Alcohol Derivatives" Molecules 19, no. 5: 6671-6682. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19056671

APA StyleHui, Z., Zhang, M., Cong, L., Xia, M., & Dong, J. (2014). Synthesis and Antiproliferative Effects of Amino-Modified Perillyl Alcohol Derivatives. Molecules, 19(5), 6671-6682. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19056671