Solid State Structure and Solution Thermodynamics of Three-Centered Hydrogen Bonds (O∙∙∙H∙∙∙O) Using N-(2-Benzoyl-phenyl) Oxalyl Derivatives as Model Compounds

Abstract

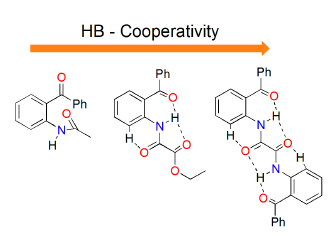

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Molecular Structure of 1–3 in the Solid State

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atoms | Bond Lengths (Å) | ||

| O8–C8 | 1.234(2) | 1.204(3) | 1.211(4) |

| O13–C13 | 1.217(2) | 1.227(2) | 1.223(5) |

| N7–C1 | 1.425(2) | 1.399(2) | 1.402(4) |

| N7–C8 | 1.338(2) | 1.346(2) | 1.350(4) |

| C1–C2 | 1.398(2) | 1.416(3) | 1.407(4) |

| C2–C13 | 1.491(2) | 1.486(2) | 1.483(5) |

| C8–C9(8a) | 1.502(2) | 1.538(3) | 1.548(5) |

| C13–C14 | 1.490(3) | 1.496(2) | 1.495(5) |

| Bond and Torsion Angles (°) | |||

| C1–N7–C8 | 123.27(14) | 129.61(16) | 128.9(3) |

| N7–C1–C2 | 121.49(14) | 119.08(16) | 118.8(3) |

| C2–C1–N7–C8 | 52.3(2) | −171.96(18) | −174.7(3) |

| O8–C8–N7–C1 | −3.2(3) | −5.8(3) | −1.2(6) |

| O8–C8–C8a–O8a | 166.7(2) | −180.0(3) | |

| O13–C13–C14–C15 | −135.18(17) | 151.65(18) | −40.2(4) |

| C1–C2–C13–O13 | −145.02(17) | 25.4(3) | 19.14(4) |

| Comp. | D–H∙∙∙A | Symmetry Code | D–H (Å) | H∙∙∙A (Å) | D∙∙∙A (Å) | D–H∙∙∙A (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N7–H7∙∙∙O8 | −½+x, 1−y, −½+z | 0.88 | 1.91 | 2.7491(19) | 160 |

| C17–H17∙∙∙O8 | −1+x, y, z | 0.95 | 2.50 | 3.439(2) | 170 | |

| C4–H4∙∙∙ Cg(2) | ½+x, −y, −½+z | 2.54 | 3.4104(19) | 153 | ||

| 2 | N7–H7∙∙∙O9 | 0.86 | 2.25 | 2.666(2) | 110 | |

| N7–H7∙∙∙O13 | 0.86 | 1.97 | 2.662(2) | 136 | ||

| C6–H6∙∙∙O8 | 0.93 | 2.29 | 2.908(3) | 124 | ||

| C17–H17∙∙∙O8 | −1+x, y, −1+z | 0.93 | 2.57 | 3.391(3) | 147 | |

| 3 | N7–H7∙∙∙O8a | −x, −y, 1−z | 0.86 | 2.23 | 2.665(4) | 111 |

| N7–H7∙∙∙O13 | 0.86 | 1.98 | 2.673(4) | 137 | ||

| C6–H6∙∙∙O8 | 0.93 | 2.27 | 2.900(4) | 124 | ||

| C4–H4∙∙∙Cg(2) | 1−x, −y, −z | 2.81 | 3.612(4) | 145 |

2.2. Supramolecular Structure of 1–3 in Solid State

2.3. Molecular Structure of 1–3 in Solution

| Comp. | (DMSO-d6) | (CDCl3) | ΔδNH b | ΔδH6 c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δCO | δNH | δH6 | −ΔδNH/ΔT a | δNH | δH6 | |||

| 1 | 169.2 | 10.1 | 7.65 | 2.59 | 10.8 | 8.63 | −0.7 | −0.98 |

| 2 | 155.6 | 11.5 | 8.06 | 2.67 | 12.3 | 8.71 | −0.8 | −0.65 |

| 3 | 158.4 | 11.7 | 8.23 | 1.88 | 12.5 | 8.81 | −0.8 | −0.58 |

| Comp. | Δ Hº/kJ·mol−1 | Δ Sº/J·mol−1·K−1 |

|---|---|---|

| Acetanilide [24] | 9.57(0.02) | 16.68(0.07) |

| Ethyl N-phenyl oxalamate [24] | 11.82(0.08) | 23.2(0.2) |

| N1,N2-bis(2-nitrophenyl)oxalamide [24] | 21.1(0.2) | 58.1(0.5) |

| 1 | 6.60(0.03) | 12.9(0.1) |

| 2 | 12.10(0.08) | 23.7(0.2) |

| 3 | 28.3(0.1) | 69.1(0.4) |

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Instruments

| Compounds | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCDC number | 1013358 | 1013356 | 1013357 |

| Formula | C15H13N1O2 | C17H15N1O4 | C28H20N8O4 |

| M (g·mol−1) | 252.0 | 297.3 | 448.5 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P n | P 21/c | P 21/c |

| a (Å) | 8.3679(9) | 9.3796(8) | 6.2377(6) |

| b (Å) | 9.1351(10) | 15.2202(13) | 17.7892(18) |

| c (Å) | 8.9361(9) | 10.6317(9) | 10.8548(9) |

| α (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β (°) | 115.320(2) | 102.815(1) | 114.429(4) |

| γ (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 618.94(7) | 1478.41(4) | 1096.6(2) |

| Z | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| ρcalcd. (g·cm−3) | 1.324 | 1.34 | 1.36 |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.086 | 0.096 | 0.092 |

| F (000) | 252.0 | 623.9 | 467.9 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.50 × 0.50 × 0.40 | 0.36 × 0.30 × 0.28 | 0.40 × 0.30 × 0.30 |

| Temp. (K) | 100 (2) | 293(2) | 100(2) |

| θ range (°) | 2.2–26.0 | 2.2–27.6 | 2.3–25.0 |

| Reflections collected | 6206 | 16595 | 9547 |

| Independent reflections | 2419 | 3381 | 1930 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 2419/2/163 | 3381/0/199 | 1930/0/154 |

| Goof | 1.139 | 1.216 | 1.148 |

| R (int) | 0.030 | 0.029 | 0.068 |

| Final R indices [I > 2σ(I)], R1/wR2 | 0.035/0.090 | 0.066/0.150 | 0.077/0.142 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole (e·Å−3) | 0.284/−0.222 | 0.230/−0.258 | 0.201/−0.185 |

3.2. Synthesis of Compounds

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jeffrey, G.A. Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Desiraju, G.R.; Steiner, T. The weak hydrogen bond. In Structural Chemistry and Biology; Monographs on Crystallography, 9th ed.; International Union of Crystallography; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, S.; Nowick, J.S. A new artificial β-sheet that dimerizes through parallel β-sheet interactions. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakshoor, O.; Nowick, J.S. Use of disulfide “staples” to stabilize β-sheet quaternary structure. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3000–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frkanec, L.; Žinić, M. Chiral bis(amino acid)- and bis(amino alcohol)-oxalamide gelators. Gelation properties, self-assembly motifs and chirality effects. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 522–537. [Google Scholar]

- Preissner, R.; Egner, U.; Saenger, W. Occurrence of bifurcated three-center hydrogen bonds in proteins. FEBS Lett. 1991, 288, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, V.; Westhof, E. Three-center hydrogen bonds in DNA: Molecular dynamics of poly(dA).cntdot.poly(dT). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 8271–8277. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Lu, Z.; Wang, J.; Yao, L.; Li, Y.; Yan, H. NMR detection of bifurcated hydrogen bonds in large proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2428–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Kennard, O.; Versichel, W. Geometry of the nitrogen-hydrogen∙∙∙oxygen-carbon (N–H∙∙∙O=C) hydrogen bond. 2. Three-center (bifurcated) and four-center (trifurcated) bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, G.A.; Maluszynska, H. A survey of the geometry of hydrogen bonds in the crystal structures of barbiturates, purines and pyrimidines. J. Mol. Struct. 1986, 147, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Christianson, L.A.; Gellman, S.H. Comparison of an HXH three-center hydrogen bond with alternative two-center hydrogen bonds in a model system. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R.D.; Zeng, H.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, C.; Zeng, X.C.; Gong, B. Stable three-center hydrogen bonding in a partially rigidified structure. Chem. Eur. J. 2001, 7, 4352–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R.D.; Olsen, J. Cooperativity in intramolecular bifurcated hydrogen bonds: An ab initio study. J. Phys. Chem. 2008, 112, 3492–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcock, W.; Graton, J.; Laurence, C.; Luçon, C.; Trout, N. Three-centre hydrogen bonding in the complexes of syn-2,4-difluoroadamantane with 4-fluorophenol and hydrogen fluoride. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005, 18, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R.D.; Furukawa, M.; Gong, B.; Zeng, X.C. Energetics and cooperativity in three-center hydrogen bonding interactions. I. Diacetamide-X dimers (X = HCN, CH3OH). J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 6030–6035. [Google Scholar]

- Eppel, S.; Bernstein, J. Statistics-based design of multicomponent molecular crystals with the three-center hydrogen bond. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzevich, Y.; Rudzevich, V.; Schollmeyer, D.; Thondorfc, I.K.; Bohmer, V. Hydrogen bonding in dimers of tritolyl and tritosylurea derivatives of triphenylmethanes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 3938–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, J.S.; Martínez-Martínez, F.J.; García-Báez, E.V.; Cruz, A.; Morín-Sánchez, L.M.; Rojas-Lima, S.; Padilla-Martínez, I.I. Molecular complexes of diethyl N,N′-1,3-phenyldioxalamate and resorcinols: Conformational switching through intramolecular three-centered hydrogen-bonding. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 628–642. [Google Scholar]

- Fulara, A.; Dzwolak, W. Bifurcated hydrogen bonds stabilize fibrils of poly(l-glutamic) acid. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 8278–8283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Liu, B.; Zou, B. High-pressure-induced reversible phase transition in sulfamide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 18640–18645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Yamato, K.; Yang, L.; Ferguson, J.S.; Zhong, L.; Zou, S.; Yuan, L.; Zeng, X.-C.; Gong, B. Efficient kinetic macrocyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2629–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fang, Y.; Deng, P.; Hu, J.; Li, T.; Feng, W.; Yuan, L. Self-complementary quadruply hydrogen-bonded duplexes based on imide and urea units. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4628–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R.D.; Streu, K. Cooperative effects in regular and bifurcated intramolecular OH∙∙∙O=C interactions: A computational study. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2011, 977, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Castro, C.Z.; Padilla-Martínez, I.I.; Martínez-Martínez, F.J.; García-Báez, E.V. Thermodynamic characterization of three centered hydrogen bond using o-aromatic amides, oxalamates and bis-oxalamides as model compounds. ARKIVOC 2008, 227, 244. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, S.L.; Song, D.; Sun, C.; Hajduk, P.J.; Petros, A.M. Labeled ligand displacement: Extending NMR-based screening of protein targets. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.; Alphey, M.S.; Jones, D.C.; Shanks, E.J.; Street, I.P.; Frearson, J.A.; Wyatt, P.G.; Gilbert, I.H.; Fairlamb, A.H. Dihydroquinazolines as a novel class of trypanosoma brucei trypanothione reductase inhibitors: Discovery, synthesis, and characterization of their binding mode by protein crystallography. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6514–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.A. An efficient synthesis of 4-phenyl-2-aminoquinolines. Synth. Comm. 1991, 21, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerstner, A.; Jumbam, D.N. Titanium-induced syntheses of furans, benzofurans and indoles. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 5991–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, Y. SmI2 mediated synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted indole derivatives. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 1917–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, X. Facile preparation of 2,3-disubstituted indole derivatives through low-valent titanium induced intramolecular reductive coupling reactions of acylamid. J. Chem. Res. Synopses 2003, 11, 696–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.K.; Lee, J.J. Facile synthesis of 4-phenylquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives from N-acyl-o-aminobenzophenones. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 2993–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulenko, V.I.; Alekseev, N.N.; Golyak, V.M.; Nikolyukin, Y.A. 4-Aza-2-benzopyrylium salts. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1976, 12, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannhardt, G.; Fiebich, B.L.; Schweppenhauser, J. COX-1/COX-2 inhibitors based on the methanone moiety. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 37, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerstner, A.; Ptock, A.; Weintritt, H.; Goddard, R.; Krueger, C. Titanium-induced zipper reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerstner, A.; Hupperts, A.; Seidel, G. Ethyl 5-chloro-3-phenylindole-2-carboxylate. Org. Synth. 1999, 76, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Wang, Q.-L.; Yang, G.-M. Synthesis, crystal structures and spectroscopic properties of two novel oxamido-bridged trinuclear complexes [Cu2M] (M = Cu, Zn). Transit. Metal. Chem. 2006, 31, 856–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Yu, M.; Wang, Q.-L.; Xu, G.-F.; Hu, M.; Yang, G.-M.; Liao, D.-Z. A macrocyclic oxamido vanadium(IV)-oxo ligand and its derivative VOIV 2MII (M = Cu, Mn) trinuclear complexes: Synthesis, structures and magnetic properties. Polyhedron 2008, 27, 3371–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.S.C.; Vanderzalm, C.H.B.; Wong, L.C.H. Metal template reactions. XIV. Synthesis of macrocyclic metal complexes from 2,2'-(oxalyldiimino)bisbenzaldehyde and related oxamido aldehydes and ketones. Aust. J. Chem. 1982, 35, 2435–2443. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.J.; Cobridge, D.E. The crystal structure of acetanilide. Acta Crystallogr. 1954, 7, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J. Further refinement of the crystal structure of acetanilide. Acta Crystallogr. 1966, 21, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, H.J.; Ryan, R.R.; Layne, S.P. Structure of acetanilide (C8H9NO) at 113 K. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1985, 41, 783–785. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, H.L.; Rozynski, H.; Crundwell, G.; Glagovich, N.M. N-(2-Acetylphenyl)acetamide. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E: Struct. Rep. 2006, 62, o1957–o1958. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, G.A.; Jasinski, J.P.; Butcher, R.J.; Scheidt, W.R. N,N'-Bis(2-acetylphenyl)ethanediamide, a second polymorph. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E: Struct. Rep. 2007, 63, o4889. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, G.A.; Jasinski, J.P.; Butcher, R.J.; Scheidt, W.R. N,N'-Bis(2-acetylphenyl)ethanediamide. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E: Struct. Rep. 2007, 63, o4887–o4888. [Google Scholar]

- Dewar, M.J.S.; Schmeizing, H.N. Resonance and conjugation—II. Factors determining bond lengths and heats of formation. Tetrahedron 1968, 11, 96–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dugave, C.; Demange, L. Cis-trans isomerization of organic molecules and biomolecules: Implications and applications. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2475–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.; Davis, R.E.; Shimoni, L.; Chang, N.-L. Patterns in hydrogen bonding: Functionality and graph set analysis in crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1555–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martínez, F.J.; Padilla-Martínez, I.I.; Brito, M.A.; Geniz, E.D.; Rojas, R.C.; Saavedra, J.B.; Höpfl, H.; Tlahuextl, M.; Contreras, R. Three-center intramolecular hydrogen bonding in oxamide derivatives. NMR and X-ray diffraction study. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1998, 2, 401–406. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Martínez, I.I.; Martínez-Martínez, F.J.; García-Báez, E.V.; Torres-Valencia, J.M.; Rojas-Lima, S.; Höpfl, H. Further insight into three center hydrogen bonding. Participation in tautomeric equilibria of heterocyclic amides. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 2001, 9, 1817–1823. [Google Scholar]

- Nishio, M. CH/π Hydrogen bonds in crystals. CrystEngComm 2004, 6, 130–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.H.; Baalham, C.A.; Lommerse, J.P.M.; Raithby, P.R. Carbonyl-carbonyl interactions can be competitive with hydrogen bonds. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 1998, 54, 320–329. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert, F.; Mills, J.F.; Nyburg, S.C.; Parkins, A.W. Hydrogen bonding and structure of 2-hydroxy-N-acylanilines in the solid state and in solution. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1998, 3, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R.D.; Gong, B.; Zeng, X.C. Energetics and cooperativity in three-center hydrogen bonding interactions. II. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 6036–6041. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, H. Conformation and biological activity of cyclic peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1982, 21, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llor, J.; Muñoz, L. Tautomeric equilibrium of pyridoxine in water. Thermodynamic characterization by 13C and 15N Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 2716–2722. [Google Scholar]

- Bruker. APEX II, SAINT, SADABS and SHELXTL; Bruker AXS Inc: Madison, WI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXS97 and SHELXL97; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Spek, A.L. PLATON, Version of March 2002; University of Utrecht: Heidelberglaan, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia, L.J. WinGX suite for small molecule single crystal crystallography. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1999, 32, 837–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Shields, G.P.; Taylor, R.; Towler, M.; van de Streek, J. Mercury: Visualization and analysis of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006, 39, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 1–3 are available from the authors.

© 2014 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Gómez-Castro, C.Z.; Padilla-Martínez, I.I.; García-Báez, E.V.; Castrejón-Flores, J.L.; Peraza-Campos, A.L.; Martínez-Martínez, F.J. Solid State Structure and Solution Thermodynamics of Three-Centered Hydrogen Bonds (O∙∙∙H∙∙∙O) Using N-(2-Benzoyl-phenyl) Oxalyl Derivatives as Model Compounds. Molecules 2014, 19, 14446-14460. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules190914446

Gómez-Castro CZ, Padilla-Martínez II, García-Báez EV, Castrejón-Flores JL, Peraza-Campos AL, Martínez-Martínez FJ. Solid State Structure and Solution Thermodynamics of Three-Centered Hydrogen Bonds (O∙∙∙H∙∙∙O) Using N-(2-Benzoyl-phenyl) Oxalyl Derivatives as Model Compounds. Molecules. 2014; 19(9):14446-14460. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules190914446

Chicago/Turabian StyleGómez-Castro, Carlos Z., Itzia I. Padilla-Martínez, Efrén V. García-Báez, José L. Castrejón-Flores, Ana L. Peraza-Campos, and Francisco J. Martínez-Martínez. 2014. "Solid State Structure and Solution Thermodynamics of Three-Centered Hydrogen Bonds (O∙∙∙H∙∙∙O) Using N-(2-Benzoyl-phenyl) Oxalyl Derivatives as Model Compounds" Molecules 19, no. 9: 14446-14460. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules190914446

APA StyleGómez-Castro, C. Z., Padilla-Martínez, I. I., García-Báez, E. V., Castrejón-Flores, J. L., Peraza-Campos, A. L., & Martínez-Martínez, F. J. (2014). Solid State Structure and Solution Thermodynamics of Three-Centered Hydrogen Bonds (O∙∙∙H∙∙∙O) Using N-(2-Benzoyl-phenyl) Oxalyl Derivatives as Model Compounds. Molecules, 19(9), 14446-14460. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules190914446