Syntheses and Biological Studies of Cu(II) Complexes Bearing Bis(pyrazol-1-yl)- and Bis(triazol-1-yl)-acetato Heteroscorpionate Ligands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Instruments

2.2. Synthesis

2.2.1. Synthesis of [HC(COOH)(pzMe2)2]Cu[HC(COO)(pzMe2)2]·ClO4, (1)

2.2.2. Synthesis of [HC(COOH)(pz)2]2Cu(ClO4)2, (2)

2.2.3. Synthesis of [HC(COOH)(tz)2]2Cu(ClO4)2·CH3OH, (3)

2.3. X-ray Crystallography

2.4. Experiments with Human Cells

2.4.1. Cell Cultures

2.4.2. Spheroid Cultures

2.4.3. Cytotoxicity Assays

MTT Assay

Acid Phosphatase (APH) Assay

2.4.4. Cellular Uptake

2.4.5. ROS Production

2.4.6. Proteasome Inhibition

2.4.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy Analyses

2.4.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis

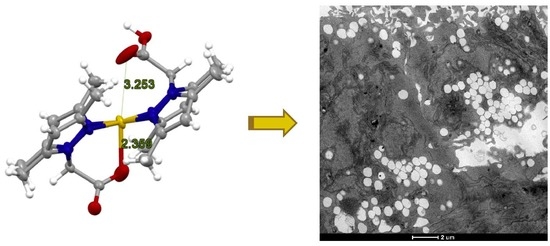

3.2. X-ray Crystallography

3.3. Biological Studies

3.3.1. Activity in Monolayer and 3D Spheroid Cancer Cell Cultures

3.3.2. Cellular Uptake Studies

3.3.3. Oxidative Stress and Effects on the Ubiquitin-proteasome System

3.3.4. TEM Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santini, C.; Pellei, M.; Gandin, V.; Porchia, M.; Tisato, F.; Marzano, C. Advances in Copper Complexes as Anticancer Agents. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 815–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisato, F.; Marzano, C.; Porchia, M.; Pellei, M.; Santini, C. Copper in Diseases and Treatments, and Copper-Based Anticancer Strategies. Med. Res. Rev. 2010, 30, 708–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzano, C.; Pellei, M.; Tisato, F.; Santini, C. Copper complexes as anticancer agents. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, K.; Bineva-Todd, G.; Eskandari, A.; Lu, C.; O’Reilly, N.; Suntharalingam, K. A Copper(II) Phenanthroline Metallopeptide That Targets and Disrupts Mitochondrial Function in Breast Cancer Stem Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandin, V.; Ceresa, C.; Esposito, G.; Indraccolo, S.; Porchia, M.; Tisato, F.; Santini, C.; Pellei, M.; Marzano, C. Therapeutic potential of the phosphino Cu(I) complex (HydroCuP) in the treatment of solid tumors. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagner, D.; Fresch, B.; Browne, K.; Gandin, V.; Erxleben, A. A Cu(ii) complex targeting the translocator protein: In vitro and in vivo antitumor potential and mechanistic insights. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendiran, D.; Kumar, R.S.; Viswanathan, V.; Velmurugan, D.; Rahiman, A.K. In vitro and in vivo anti-proliferative evaluation of bis(4′-(4-tolyl)-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine)copper(II) complex against Ehrlich ascites carcinoma tumors. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 22, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.-P.; Liu, Y.-C.; Wang, H.-L.; Qin, J.-L.; Cheng, F.-J.; Tang, S.-F.; Liang, H. Synthesis and antitumor mechanisms of a copper(ii) complex of anthracene-9-imidazoline hydrazone (9-AIH). Metallomics 2015, 7, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becco, L.; García-Ramos, J.C.; Azuara, L.R.; Gambino, D.; Garat, B. Analysis of the DNA Interaction of Copper Compounds Belonging to the Casiopeínas® Antitumoral Series. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2014, 161, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandin, V.; Tisato, F.; Dolmella, A.; Pellei, M.; Santini, C.; Giorgetti, M.; Marzano, C.; Porchia, M. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of copper(I) complexes with homoscorpionate tridentate tris(pyrazolyl)borate and auxiliary monodentate phosphine ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4745–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanimuthu, D.; Shinde, S.V.; Somasundaram, K.; Samuelson, A.G. In Vitro and in Vivo Anticancer Activity of Copper Bis(thiosemicarbazone) Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, N.; Jeyamurugan, R.; Senthilkumar, R.; Rajkapoor, B.; Franzblau, S.G. In vivo and in vitro evaluation of highly specific thiolate carrier group copper(II) and zinc(II) complexes on Ehrlich ascites carcinoma tumor model. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 5438–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandin, V.; Pellei, M.; Tisato, F.; Porchia, M.; Santini, C.; Marzano, C. A novel copper complex induces paraptosis in colon cancer cellsviathe activation of ER stress signalling. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012, 16, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weekley, C.M.; He, C. Developing drugs targeting transition metal homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 37, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Platas, C.; Guerrero-Beltrán, C.E.; Carrancá, M.; Castillo, E.C.; Bernal-Ramírez, J.; Oropeza-Almazán, Y.; González, L.N.; Rojo, R.; Martínez, L.E.; Valiente-Banuet, J.; et al. Antineoplastic copper coordinated complexes (Casiopeinas) uncouple oxidative phosphorylation and induce mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac mitochondria and cardiomyocytes. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2016, 48, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denoyer, D.; Masaldan, S.; La Fontaine, S.; Cater, M.A. Targeting copper in cancer therapy: ‘Copper That Cancer’. Metallomics 2015, 7, 1459–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandin, V.; Trenti, A.; Porchia, M.; Tisato, F.; Giorgetti, M.; Zanusso, I.; Trevisi, L.; Marzano, C. Homoleptic phosphino copper(i) complexes with in vitro and in vivo dual cytotoxic and anti-angiogenic activity. Metallomics 2015, 7, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, M.; Arjmand, F.; Tabassum, S. Current and future potential of metallo drugs: Revisiting DNA-binding of metal containing molecules and their diverse mechanism of action. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2016, 444, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allardyce, C.S.; Dyson, P.J. Metal-based drugs that break the rules. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 3201–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spreckelmeyer, S.; Orvig, C.; Casini, A. Cellular Transport Mechanisms of Cytotoxic Metallodrugs: An Overview beyond Cisplatin. Molecules 2014, 19, 15584–15610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tardito, S.; Barilli, A.; Bassanetti, I.; Tegoni, M.; Bussolati, O.; Franchi-Gazzola, R.; Mucchino, C.; Marchiò, L. Copper-Dependent Cytotoxicity of 8-Hydroxyquinoline Derivatives Correlates with Their Hydrophobicity and Does Not Require Caspase Activation. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10448–10459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barilli, A.; Atzeri, C.; Bassanetti, I.; Ingoglia, F.; Dall’Asta, V.; Bussolati, O.; Maffini, M.; Mucchino, C.; Marchiò, L. Oxidative Stress Induced by Copper and Iron Complexes with 8-Hydroxyquinoline Derivatives Causes Paraptotic Death of HeLa Cancer Cells. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehbe, M.; Leung, A.W.Y.; Abrams, M.J.; Orvig, C.; Bally, M.B. A Perspective—can copper complexes be developed as a novel class of therapeutics? Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 10758–10773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medici, S.; Peana, M.; Nurchi, V.M.; Lachowicz, J.I.; Crisponi, G.; Zoroddu, M.A. Noble metals in medicine: Latest advances. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 284, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellei, M.; Gioia Lobbia, G.; Papini, G.; Santini, C. Synthesis and properties of poly(pyrazolyl)borate and related boron-centered scorpionate ligands. Part B: Imidazole-, triazole- and other heterocycle-based systems. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2010, 7, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimenko, S. Scorpionates: The Coordination Chemistry of Poly(pyrazolyl)borate Ligands; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 1999; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, A.; Fernandez-Baeza, J.; Tejeda, J.; Antinolo, A.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, F.; Diez-Barra, E.; Lara-Sanchez, A.; Fernandez-Lopez, M.; Lanfranchi, M.; Pellinghelli, M.A. Syntheses and crystal structures of lithium and niobium complexes containing a new type of monoanionic "scorpionate" ligand. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1999, 3537–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Weibert, B.; Burzlaff, N. Monoanionic N,N,O-scorpionate ligands and their iron(II) and zinc(II) complexes: Models for mononuclear active sites of non-heme iron oxidases and zinc enzymes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 2001, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzlaff, N.; Hegelmann, I.; Weibert, B. Bis(pyrazol-1-yl)acetates as tripodal "scorpionate" ligands in transition metal carbonyl chemistry: Syntheses, structures and reactivity of manganese and rhenium carbonyl complexes of the type [LM(CO)3] (L. = bpza, bdmpza). J. Organomet. Chem. 2001, 626, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkorta, I.; Claramunt, R.M.; Díez-Barra, E.; Elguero, J.; de la Hoz, A.; López, C. The organic chemistry of poly(1H-pyrazol-1-yl)methanes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 339, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, A.; Fernández-Baeza, J.; Lara-Sánchez, A.; Sánchez-Barba, L.F. Metal complexes with heteroscorpionate ligands based on the bis(pyrazol-1-yl)methane moiety: Catalytic chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 1806–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, A.; Fernandez-Baeza, J.; Antinolo, A.; Tejeda, J.; Lara-Sanchez, A. Heteroscorpionate ligands based on bis(pyrazol-1-yl)methane: Design and coordination chemistry. Dalton Trans. 2004, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, T.; Rodehutskors, P.M.; Schmidt, J.; Burzlaff, N. Oxygen Atom Transfer Catalysis with Homogenous and Polymer-Supported N,N- and N,N,O-Heteroscorpionate Dioxidomolybdenum(VI) Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016, 2595–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlevar, B.; Jakomin, K.; Pokaj, M.; Jagliic, Z.; Beyer, A.; Burzlaff, N.; Kitanovski, N. Dinuclear Nitrato Coordination Compounds with Bis(3,5-tert-butylpyrazol-1-yl)acetate. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 2015, 3688–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkoglu, G.; Pubill Ulldemolins, C.; Müller, R.; Hübner, E.; Heinemann, F.W.; Wolf, M.; Burzlaff, N. Bis(3,5-dimethyl-4-vinylpyrazol-1-yl)acetic Acid: A New Heteroscorpionate Building Block for Copolymers that Mimic the 2-His-1-carboxylate Facial Triad. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 2010, 2962–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N.V.; Türkoglu, G.; Burzlaff, N. Scorpionate complexes suitable for enzyme inhibitor studies. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2009, 5, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzlaff, N. Tripodal N,N,O-ligands for metalloenzyme models and organometallics. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 60, pp. 101–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hammes, B.S.; Chohan, B.S.; Hoffman, J.T.; Einwaechter, S.; Carrano, C.J. A family of dioxo-molybdenum(VI) complexes of N2X heteroscorpionate ligands of relevance to molybdoenzymes. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 7800–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas, M.; Mehn, M.P.; Jensen, M.P.; Que Jr, L. Dioxygen Activation at Mononuclear Nonheme Iron Active Sites: Enzymes, Models, and Intermediates. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 939–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, G. Synthetic Analogues Relevant to the Structure and Function of Zinc Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 699–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammes, B.S.; Kieber-Emmons, M.T.; Letizia, J.A.; Shirin, Z.; Carrano, C.J.; Zakharov, L.N.; Rheingold, A.L. Synthesis and characterization of several zinc(II) complexes containing the bulky heteroscorpionate ligand bis(5-tert-butyl-3-methylpyrazol-2-yl)acetate: Relevance to the resting states of the zinc(II) enzymes thermolysin and carboxypeptidase A. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2003, 346, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Barth, A.; Hubner, E.; Burzlaff, N. Bis(pyrazol-1-yl)acetates as Tripodal Heteroscorpionate Ligands in Iron Chemistry: Syntheses and Structures of Iron(II) and Iron(III) Complexes with bpza, bdmpza, and bdtbpza Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 7182–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.B.; Amantini, C.; Santoni, G.; Pellei, M.; Santini, C.; Cimarelli, C.; Marcantoni, E.; Petrini, M.; Del Bello, F.; Giorgioni, G.; et al. Novel antitumor copper(ii) complexes designed to act through synergistic mechanisms of action, due to the presence of an NMDA receptor ligand and copper in the same chemical entity. New, J. Chem. 2018, 42, 11878–11887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellei, M.; Gandin, V.; Cimarelli, C.; Quaglia, W.; Mosca, N.; Bagnarelli, L.; Marzano, C.; Santini, C. Syntheses and biological studies of nitroimidazole conjugated heteroscorpionate ligands and related Cu(I) and Cu(II) complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 187, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgetti, M.; Tonelli, S.; Zanelli, A.; Aquilanti, G.; Pellei, M.; Santini, C. Synchrotron radiation X-ray absorption spectroscopic studies in solution and electrochemistry of a nitroimidazole conjugated heteroscorpionate copper(II) complex. Polyhedron 2012, 48, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellei, M.; Papini, G.; Trasatti, A.; Giorgetti, M.; Tonelli, D.; Minicucci, M.; Marzano, C.; Gandin, V.; Aquilanti, G.; Dolmella, A.; et al. Nitroimidazole and glucosamine conjugated heteroscorpionate ligands and related copper(II) complexes. Syntheses, biological activity and XAS studies. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 9877–9888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quillian, B.; Lynch, W.E.; Padgett, C.W.; Lorbecki, A.; Petrillo, A.; Tran, M. Syntheses and Crystal Structures of Copper(II) Bis(pyrazolyl)acetic Acid Complexes. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Das, K.; Beyene, B.B.; Garribba, E.; Gajewska, M.J.; Hung, C.-H. EPR interpretation and electrocatalytic H2 evolution study of bis(3,5-di-methylpyrazol-1-yl)acetate anchored Cu(II) and Mn(II) complexes. Mol. Catal. 2017, 439, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewska, M.J.; Ching, W.M.; Wen, Y.S.; Hung, C.H. Synthesis, structure, and catecholase activity of bispyrazolylacetate copper(ii) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14726–14736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlevčar, B.; Gamez, P.; de Gelder, R.; Jagličić, Z.; Strauch, P.; Kitanovski, N.; Reedijk, J. Counterion and Solvent Effects on the Primary Coordination Sphere of Copper(II) Bis(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl)acetic Acid Coordination Compounds. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 3650–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkoglu, G.; Heinemann, F.W.; Burzlaff, N. Transition metal complexes bearing a 2,2-bis(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl) propionate ligand: One methyl more matters. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 4678–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlevčar, B.; Pregelj, T.; Pevec, A.; Kitanovski, N.; Costa, J.S.; Van Albada, G.; Gamez, P.; Reedijk, J. Copper complexes with the ligand methyl bis(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl)- acetate (Mebdmpza), generated by in situ methanolic esterification of bis(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl)acetic acid. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 2008, 4977–4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, E.; Türkoglu, G.; Wolf, M.; Zenneck, U.; Burzlaff, N. Novel N,N,O scorpionate ligands and transition metal complexes thereof suitable for polymerisation. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 2008, 1226–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Zhang, Z.H.; Tang, L.F.; Wang, X.G.; Zhao, X.J.; Batten, S.R. Molecular tectonics of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs): A rational design strategy for unusual mixed-connected network topologies. Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 2578–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevec, A.; Kozlevčar, B.; Gamez, P.; Reedijk, J. Hexakis-μ-chlorido-dichloridobis[(3,5-dimethyl-pyrazol-1-yl)acetic acid-κ2N,N’]tetracopper(II): An unexpected neutral bis-pyrazolyl ligand in a tetracopper(II) complex. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online 2007, 63, m514–m516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, V.; Thilagar, P.; Senapati, T. Transition metal-assisted hydrolysis of pyrazole-appended organooxotin carboxylates accompanied by ligand transfer. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 2007, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlevčar, B.; Golobič, A.; Gamez, P.; Koval, I.A.; Driessen, W.L.; Reedijk, J. A tridentate bis(pyrazolyl) ligand binds to Cu(II), without using the pyrazole group: A very unusual coordination mode of the ligand Hbdmpb, 1,3-bis(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl)-2-butanoic acid. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2005, 358, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlevčar, B.; Gamez, P.; De Gelder, R.; Driessen, W.L.; Reedijk, J. Unprecedented change of the Jahn-Teller axis in a centrosymmetric CuII complex induced by lattice water molecules—Crystal and molecular structures of bis[bis(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl)acetate]copper(II) and its dihydrate. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 2003, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, C.; Pellei, M.; Colavito, D.; Alidori, S.; Lobbia, G.G.; Gandin, V.; Tisato, F.; Santini, C. Synthesis, Characterization, and in Vitro Antitumor Properties of Tris(hydroxymethyl)phosphine Copper(I) Complexes Containing the New Bis(1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)acetate Ligand. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 7317–7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetollo, F.; Gioia Lobbia, G.; Mancini, M.; Pellei, M.; Santini, C. Synthesis, characterization and hydrolytic behavior of new bis(2-pyridylthio)acetate ligand and related organotin(IV) complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 690, 1994–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porchia, M.; Papini, G.; Santini, C.; Lobbia, G.G.; Pellei, M.; Tisato, F.; Bandoll, G.; Dolmella, A. Novel rhenium(V) oxo complexes containing bis(pyrazol-1-yl)acetate and bis(pyrazol-1-yl) sulfonate as tripodal N,N,O-heteroscorplonate ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 4045–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellei, M.; Lobbia, G.G.; Santini, C.; Spagna, R.; Camalli, M.; Fedeli, D.; Falcioni, G. Synthesis, characterization and antioxidant activity of new copper(I) complexes of scorpionate and water soluble phosphane ligands. Dalton Trans. 2004, 2822–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidori, S.; Gioia Lobbia, G.; Papini, G.; Pellei, M.; Porchia, M.; Refosco, F.; Tisato, F.; Lewis Jason, S.; Santini, C. Synthesis, in vitro and in vivo characterization of (64)Cu(I) complexes derived from hydrophilic tris(hydroxymethyl)phosphane and 1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane ligands. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 13, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, A.; Lara-Sánchez, A.; Fernández-Baeza, J.; Alonso-Moreno, C.; Castro-Osma, J.A.; Márquez-Segovia, I.; Sánchez-Barba, L.F.; Rodríguez, A.M.; Garcia-Martinez, J.C. Neutral and Cationic Aluminum Complexes Supported by Acetamidate and Thioacetamidate Heteroscorpionate Ligands as Initiators for Ring-Opening Polymerization of Cyclic Esters. Organometallics 2011, 30, 1507–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, A.; Lara-Sánchez, A.; Fernández-Baeza, J.; Alonso-Moreno, C.; Tejeda, J.; Castro-Osma, J.A.; Márquez-Segovia, I.; Sánchez-Barba, L.F.; Rodríguez, A.M.; Gómez, M.V. Straightforward Generation of Helical Chirality Driven by a Versatile Heteroscorpionate Ligand: Self-Assembly of a Metal Helicate by Using CH-π Interactions. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 8615–8619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, A.; Lara-Sanchez, A.; Fernandez-Baeza, J.; Martinez-Caballero, E.; Marquez-Segovia, I.; Alonso-Moreno, C.; Sanchez-Barba, L.F.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Lopez-Solera, I. New achiral and chiral NNE heteroscorpionate ligands. Synthesis of homoleptic lithium complexes as well as halide and alkyl scandium and yttrium complexes. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, A.; Fernandez-Baeza, J.; Lara-Sanchez, A.; Alonso-Moreno, C.; Marquez-Segovia, I.; Sanchez-Barba, L.F.; Rodriguez, A.M. Ring-opening polymerization of cyclic esters by an enantiopure heteroscorpionate rare earth initiator. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2176–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.-Y.; Hong, J.; Du, M.; Tang, L.-F. New multidentate heteroscorpionate ligands: N-Phenyl-2,2-bis(pyrazol-1-yl)thioacetamide and ethyl 2,2-bis(pyrazol-1-yl)dithioacetate as well as their derivatives. J. Organomet. Chem. 2007, 692, 1708–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, A.; Fernandez-Baeza, J.; Antinolo, A.; Tejeda, J.; Lara-Sanchez, A.; Sanchez-Barba, L.; Sanchez-Molina, M.; Franco, S.; Lopez-Solera, I.; Rodriguez, A.M. Design of new heteroscorpionate ligands and their coordinative ability toward Group 4 transition metals; an efficient synthetic route to obtain enantiopure ligands. Dalton Trans. 2006, 4359–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsey, W.C. Perchlorate salts, their uses and alternatives. Journal of Chemical Education 1973, 50, A335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker, Smart (Control) and Saint (Integration) Software for CCD Systems; Bruker AXS: Madison, WI, USA, 2012.

- Krause, L.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Stalke, D. Comparison of silver and molybdenum microfocus X-ray sources for single-crystal structure determination. J. Appl. Cryst. 2015, 48, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burla, M.C.; Caliandro, R.; Camalli, M.; Carrozzini, B.; Cascarano, G.L.; De Caro, L.; Giacovazzo, C.; Polidori, G.; Spagna, R. SIR2004: An improved tool for crystal structure determination and refinement. J. Appl. Cryst. 2005, 38, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Shields, G.P.; Taylor, R.; Towler, M.; van de Streek, J. Mercury: Visualization and analysis of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006, 39, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margiotta, N.; Marzano, C.; Gandin, V.; Osella, D.; Ravera, M.; Gabano, E.; Platts, J.A.; Petruzzella, E.; Hoeschele, J.D.; Natile, G. Revisiting [PtCl2(cis-1,4-DACH)]: An Underestimated Antitumor Drug with Potential Application to the Treatment of Oxaliplatin-Refractory Colorectal Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7182–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, M.C.; Scudiero, D.A.; Monks, A.; Hursey, M.L.; Czerwinski, M.J.; Fine, D.L.; Abbott, B.J.; Mayo, J.G.; Shoemaker, R.H.; Boyd, M.R. Feasibility of drug screening with panels of human tumor cell lines using a microculture tetrazolium assay. Cancer. Res. 1988, 48, 589–601. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, W.; McIndoe, J.S. Mass Spectrometry of Inorganic, Coordination and Organometallic Compounds; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, E.; Faivre, S.; Chaney, S.; Woynarowski, J.; Cvitkovic, E. Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology of Oxaliplatin. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002, 1, 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- LaBarbera, D.V.; Reid, B.G.; Yoo, B.H. The multicellular tumor spheroid model for high-throughput cancer drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2012, 7, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomeni, G.; Cerchiaro, G.; Da Costa Ferreira, A.M.; De Martino, A.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Rotilio, G.; Ciriolo, M.R. Pro-apoptotic Activity of Novel Isatin-Schiff Base Copper(II) Complexes Depends on Oxidative Stress Induction and Organelle-selective Damage. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 12010–12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tardito, S.; Bassanetti, I.; Bignardi, C.; Elviri, L.; Tegoni, M.; Mucchino, C.; Bussolati, O.; Franchi-Gazzola, R.; Marchiò, L. Copper Binding Agents Acting as Copper Ionophores Lead to Caspase Inhibition and Paraptotic Cell Death in Human Cancer Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6235–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 1–3 are available from the authors. |

| Empirical formula | C24H31ClCuN8O8 |

| Formula weight | 658.56 |

| Temperature/K | 298 |

| Crystal system | monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/a |

| a/Å | 13.831(2) |

| b/Å | 16.048(2) |

| c/Å | 14.198(2) |

| α/° | 90 |

| β/° | 114.557(2) |

| γ/° | 90 |

| Volume/Å3 | 2866.3(7) |

| Z | 4 |

| ρcalcg/cm3 | 1.526 |

| μ/mm−1 | 0.917 |

| F(000) | 1364.0 |

| Crystal size/mm3 | 0.27 × 0.18 × 0.15 |

| Radiation | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) |

| 2θ range for data collection/° | 3.154 to 51.362 |

| Index ranges | −16 ≤ h ≤ 16, −19 ≤ k ≤ 19, −17 ≤ l ≤ 17 |

| Reflections collected | 32067 |

| Independent reflections | 5427 [Rint = 0.0546, Rsigma = 0.0344] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 5427/154/528 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.027 |

| Final R indexes [I ≥ 2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0645, wR2 = 0.1669 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole/e Å−3 | 1.50/−0.71 |

| IC50 (µM) ± S.D. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A431 | BxPC3 | HCT-15 | MCF-7 | A549 | 2008 | |

| (1) | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 10.5 ± 2.1 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 10.8 ± 1.3 |

| (2) | 12.7 ± 1.2 | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 9.3 ± 2.7 | 10.2 ± 2.5 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 7.9 ± 1.4 |

| (3) | 15.9 ± 5.8 | 18.5 ± 4.4 | 59.5 ± 2.7 | 39.6 ± 4.6 | 24.5 ± 1.9 | 69.3 ± 4.7 |

| [HC(COOH)(pzMe2)2] | ND | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| [HC(COOH)(pz)2] | ND | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| [HC(COOH)(tz)2] | ND | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| Cisplatin | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 7.3 ± 1.2 | 15.3 ± 2.2 | 8.8 ± 1.4 | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 1.0 |

| IC50 (µM) ± S.D. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| LoVo | LoVo-OXP | RF | |

| (1) | 4.2 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 1.2 |

| (2) | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 1.2 |

| (3) | 15.3 ± 1.0 | 32.5 ± 1.0 | 2.1 |

| Oxaliplatin | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 15.2 ± 2.2 | 10.9 |

| IC50 (µM) ± S.D. | |

|---|---|

| HCT-15 | |

| (1) | 67.8 ± 14.9 |

| (2) | 107.8 ± 1.0 |

| (3) | >100 |

| Cisplatin | 65.93 ± 3.85 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pellei, M.; Gandin, V.; Marchiò, L.; Marzano, C.; Bagnarelli, L.; Santini, C. Syntheses and Biological Studies of Cu(II) Complexes Bearing Bis(pyrazol-1-yl)- and Bis(triazol-1-yl)-acetato Heteroscorpionate Ligands. Molecules 2019, 24, 1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24091761

Pellei M, Gandin V, Marchiò L, Marzano C, Bagnarelli L, Santini C. Syntheses and Biological Studies of Cu(II) Complexes Bearing Bis(pyrazol-1-yl)- and Bis(triazol-1-yl)-acetato Heteroscorpionate Ligands. Molecules. 2019; 24(9):1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24091761

Chicago/Turabian StylePellei, Maura, Valentina Gandin, Luciano Marchiò, Cristina Marzano, Luca Bagnarelli, and Carlo Santini. 2019. "Syntheses and Biological Studies of Cu(II) Complexes Bearing Bis(pyrazol-1-yl)- and Bis(triazol-1-yl)-acetato Heteroscorpionate Ligands" Molecules 24, no. 9: 1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24091761

APA StylePellei, M., Gandin, V., Marchiò, L., Marzano, C., Bagnarelli, L., & Santini, C. (2019). Syntheses and Biological Studies of Cu(II) Complexes Bearing Bis(pyrazol-1-yl)- and Bis(triazol-1-yl)-acetato Heteroscorpionate Ligands. Molecules, 24(9), 1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24091761