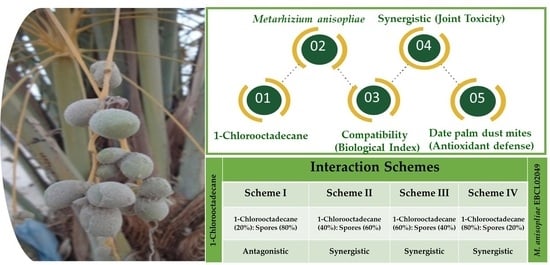

Potential Synergy between Spores of Metarhizium anisopliae and Plant Secondary Metabolite, 1-Chlorooctadecane for Effective Natural Acaricide Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Compatibility Bioassays

2.2. Screening Biossays

2.3. Host Antioxidant Defense Response

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Date Palm Dust Mites

4.2. M. anisopliae

4.3. 1-Chlorooctadecane

4.4. Compatibility of M. anisopliae Spores with 1-Chlorooctadecane

4.5. Laboratory Evaluation of M. anisopliae Spores with 1-Chlorooctadecane in Different Proportions against Date Palm Dust Mites

4.6. Exploration of Host Antioxidant Defense Response

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diallo, H. The role of date palm in combat desertification. In The Date Palm: From Traditional Resource to Green Wealth; Emirates Centre for Strategic Studies and Research: Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2005; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bashah, M. Date Varieties in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Guidance Booklet: Palms and Dates; King Abdulaziz University Press: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hadrami, I.; El-Hadrami, A. Breeding Date Palm. In Breeding Plantation Tree Crops: Tropical Species; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 191–216. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT Food and Agricultural Commodities Production. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/visualize (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Chaaban, S.B.; Chermiti, B.; Kreiter, S. Comparative demography of the spider mite, Oligonychus afrasiaticus, on four date palm varieties in Southwestern Tunisia. J. Insect Sci. 2011, 11, Article 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amer, S.A.A.; Refaat, A.M.; Momen, F.M. Repellent and oviposition-deterring activity of Rosemary and Sweet Marjoram on the spider mites Tetranychus urticae and Eutetranychus orientalis (Acari: Tetranychidae). Acta Phytopathol. Entomol. Hungarica 2001, 36, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, G.; Srinivasa, N.; Muralidhara, M.S. Potentiality of Cinnamomum extracts to two spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch and its predator Neoseiulus longispinosus (Evans). J. Biopestic. 2014, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chiasson, H.; Bélanger, A.; Bostanian, N.; Vincent, C.; Poliquin, A. Acaricidal properties of Artemisia absinthium and Tanacetum vulgare (Asteraceae) essential oils obtained by three methods of extraction. J. Econ. Entomol. 2001, 94, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, A.; Qasim, M.; Ali, H.; Qadir, Z.A.; Idrees, A.; Qing, J. Acaricidal potential of some botanicals against the stored grain mites, Rhizoglyphus tritici. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2016, 4, 611–617. [Google Scholar]

- Elkertati, M.; Blenzar, A.; Jotei, A.B.; Belkoura, I.; Tazi, B. Acaricide effect of some extracts and fractions on Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). African J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 2970–2976. [Google Scholar]

- Bussaman, P.; Sa-uth, C.; Rattanasena, P.; Chandrapatya, A. Effect of crude plant extracts on Mushroom mite, Luciaphorus sp. (Acari: Pygmephoridae). Psyche A J. Entomol. 2012, 2012, Article ID 150958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miresmailli, S.; Bradbury, R.; Isman, M.B. Comparative toxicity of Rosmarinus officinalis L. essential oil and blends of its major constituents against Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) on two different host plants. Pest Manag. Sci. 2006, 62, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Tian, M.Y.; He, Y.R.; Ahmed, S. Entomopathogenic fungi disturbed the larval growth and feeding performance of Ocinara varians (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) larvae. Insect Sci. 2009, 16, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Tian, M.Y.; He, Y.R.; Lei, Y.Y. Differential fluctuation in virulence and VOC profiles among different cultures of entomopathogenic fungi. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 104, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Tian, M.Y.; Wen, S.-Y. Proteomic analysis of Formosan Subterranean Termites during exposure to entomopathogenic fungi. Curr. Proteomics 2018, 15, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Rizwan-ul-haq, M.; AlJabr, A.M.; Al-Ayedh, H. Host-pathogen interaction for screening potential of Metarhizium anisopliae isolates against the date-palm dust mite, Oligonychus afrasiaticus (McGregor) (Acari: Tetranychidae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2019, 29, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kristiani, E.B.E.; Nugroho, L.H.; Moeljopawiro, S.; Widyarini, S. Characterization of volatile compounds of Albertisia papuana Becc root extracts and cytotoxic activity in breast cancer cell line T47D. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2016, 15, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swami, S.B.; Thakor, N.S.J.; Patil, M.M.; Haldankar, P.M. Jamun (Syzygium cumini (L.)): A review of its food and medicinal uses. Food Nutr. Sci. 2012, 3, 1100–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; He, T.; Wang, Y.; Ji, T.; Zhai, W.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X. Analysis and biological evaluation of Arisaema amuremse Maxim essential oil. Open Chem. 2019, 17, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiquee, S.; Cheong, B.E.; Taslima, K.; Kausar, H.; Hasan, M.M. Separation and identification of volatile compounds from liquid cultures of Trichoderma harzianum by GC-MS using three different Capillary Columns. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2012, 50, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fetoh, B.; Al-Shammery, K. Acaricidal ovicial and repellent activities of some plant extracts on the date palm dust mite, Oligonychus afrasiaticus Meg. (Acari: Tetranychidae). Int. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2011, 2, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhdari, W.; Dehliz, A.; Acheuk, F.; Soud, A.; Hammi, H.; Mlik, R.; Doumandji-Mitiche, B. Acaricidal activity of aqueous extracts against the mite of date palm Oligonychus afrasiaticus Meg (Acari: Tetranychidae). J. Med. Plants 2015, 3, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- AlJabr, A.; Hussain, A.; Rizwan-ul-haq, M. Toxin-Pathogen synergy reshaping detoxification and antioxidant defense mechanism of Oligonychus afrasiaticus (McGregor). Molecules 2018, 23, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussain, A.; Rizwan-ul-Haq, M.; AlJabr, A.M.; Al-Ayedh, H. Evaluation of host–pathogen interactions for selection of entomopathogenic fungal isolates against Oligonychus afrasiaticus (McGregor). BioControl 2020, 65, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.-B.; Zhang, L.; Feng, M.-G. Time-concentration-mortality responses of carmine spider mite (Acari: Tetranychidae) females to three hypocrealean fungi as biocontrol agents. Biol. Control 2008, 46, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves Diniz, A.; Barbosa, L.F.S.; da Silva Santos, A.C.; de Oliveira, N.T.; da Costa, A.F.; Carneiro-Leão, M.P.; Tiago, P.V. Bio-insecticide effect of isolates of Fusarium caatingaense (Sordariomycetes: Hypocreales) combined to botanical extracts against Dactylopius opuntiae (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wraight, S.P.; Filotas, M.J.; Sanderson, J.P. Comparative efficacy of emulsifiable-oil, wettable-powder, and unformulated-powder preparations of Beauveria bassiana against the melon aphid Aphis gossypii. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2016, 26, 894–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.M.; Martínez-Villar, E.; Peace, C.; Pérez-Moreno, I.; Marco, V. Compatibility of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana with flufenoxuron and azadirachtin against Tetranychus urticae. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2012, 58, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Rizwan-ul-Haq, M.; Al-Ayedh, H.; AlJabr, A. Susceptibility and immune defence mechanisms of Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) against entomopathogenic fungal infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussain, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, M. Laboratory and field evaluation of Metarhizium anisopliae var. anisopliae for controlling subterranean termites. Neotrop. Entomol. 2011, 40, 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A. Reprogramming the virulence: Insect defense molecules navigating the epigenetic landscape of Metarhizium robertsii. Virulence 2018, 9, 447–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussain, A.; Rizwan-ul-Haq, M.; Al-Ayedh, H.; Al-Jabr, A. Mycoinsecticides: Potential and future perspective. Recent Pat. Food. Nutr. Agric. 2014, 6, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Tian, M.Y. Germination pattern and inoculum transfer of entomopathogenic fungi and their role in disease resistance among Coptotermes formosanus (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2013, 15, 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Wink, M. Plant secondary metabolites modulate insect behavior-steps toward addiction? Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wink, M. Interference of alkaloids with neuroreceptors and ion channels. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2000, 21, 3–122. [Google Scholar]

- AlJabr, A.M.; Hussain, A.; Rizwan-ul-Haq, M.; Al-Ayedh, H. Toxicity of Plant Secondary Metabolites Modulating Detoxification Genes Expression for Natural Red Palm Weevil Pesticide Development. Molecules 2017, 22, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hussain, A.; Rizwan-ul-haq, M.; AlJabr, A.M.; Al-Ayedh, H. Lethality of Sesquiterpenes Reprogramming Red Palm Weevil Detoxification Mechanism for Natural Novel Biopesticide Development. Molecules 2019, 24, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hussain, A.; Rizwan-ul-Haq, M.; Al-Ayedh, H.; Aljabr, A.M. Toxicity and detoxification mechanism of black pepper and its major constituent in controlling Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Olivier (Curculionidae: Coleoptera). Neotrop. Entomol. 2017, 46, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-de-Cabezón Irigaray, F.J.; Marco-Mancebón, V.; Pérez-Moreno, I. The entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana and its compatibility with triflumuron: Effects on the twospotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae. Biol. Control 2003, 26, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Li, L.; Dong, T.; Zhang, B.; Hu, Q. Joint action of the entomopathogenic fungus Isaria fumosorosea and four chemical insecticides against the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2014, 24, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, W.; Lord, J.C.; Nechols, J.R.; Loughin, T.M. Efficacy of Beauveria bassiana for red flour beetle when applied with plant essential oils or in mineral oil and organosilicone carriers. J. Econ. Entomol. 2005, 98, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Liang, X.; Lu, H.; Li, Q.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, P.; Li, K.; Liu, G.; Yan, W.; Song, J.; et al. Overproduction of superoxide dismutase and catalase confers cassava resistance to Tetranychus cinnabarinus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deisseroth, A.; Dounce, A.L. Catalase: Physical and chemical properties, mechanism of catalysis, and physiological role. Physiol. Rev. 1970, 50, 319–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Tian, M.Y.; He, Y.R.; Ruan, L.; Ahmed, S. In vitro and in vivo culturing impacts on the virulence characteristics of serially passed entomopathogenic fungi. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2010, 8, 481–487. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A.; Tian, M.-Y.; Wen, S.-Y. Exploring the caste-specific multi-layer defense mechanism of Formosan Subterranean Termites, Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schumacher, V.; Poehling, H.-M. In vitro effect of pesticides on the germination, vegetative growth, and conidial production of two strains of Metarhizium anisopliae. Fungal Biol. 2012, 116, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 1925, 18, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatsDirect StatsDirect Statistical Software. England. StatsDirect Ltd., 2013. Available online: http://www.statsdirect.com (accessed on 25 February 2020).

- Statistix Statistix 8.1; Analytical Software: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2003.

- Sun, Y.-P.; Johnson, E.R. Analysis of joint action of insecticides against House flies. J. Econ. Entomol. 1960, 53, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute SAS User’s Guide: Statistics; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2000.

Sample Availability: Samples of the compound, 1-Chlorooctadecane and Metarhizium anisopliae EBCL 02049 are available from the authors. |

| Treatments | Vegetative Growth (mm) 1 | Germination (%) 1 | Sporulation (×106 Spores/mL) 1 | Biological Index | Classification 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 85.70 ± 2.25a | 98.70 ± 0.79a | 7.80 ± 0.63a | - | - |

| 0.8 mg/mL | 84.40 ± 2.28ab | 98.20 ± 0.99a | 7.30 ± 0.60ab | 96.48 | Compatible |

| 1.6 mg/mL | 84.20 ± 21.69ab | 97.90 ± 1.03a | 6.40 ± 0.54abc | 91.38 | Compatible |

| 2.4 mg/mL | 79.30 ± 1.82bc | 97.30 ± 0.71a | 6.20 ± 0.61bc | 87.53 | Compatible |

| 3.2 mg/mL | 78.10 ± 2.11c | 96.70 ± 0.93a | 5.60 ± 0.40c | 83.50 | Compatible |

| 4.0 mg/mL | 77.70 ± 1.54c | 97.20 ± 0.81a | 5.50 ± 0.34c | 82.78 | Compatible |

| Combinations | LC50 (mg/mL) | Joint Toxicity | Interaction 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme I: 20% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 80% Spores | |||

| 0.16 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 3.2 mg/mL spores | 8.75 (7.10–10.75) | 47 | Antagonistic |

| 0.32 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 6.4 mg/mL spores | |||

| 0.48 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 9.6 mg/mL spores | |||

| 0.64 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 12.8 mg/mL spores | |||

| 0.80 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 16.0 mg/mL spores | |||

| Scheme II: 40% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 60% Spores | |||

| 0.32 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 2.4 mg/mL spores | 4.62 (3.41–5.65) | 112 | Synergistic |

| 0.64 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 4.8 mg/mL spores | |||

| 0.96 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 7.2 mg/mL spores | |||

| 1.28 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 9.6 mg/mL spores | |||

| 1.60 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 12 mg/mL spores | |||

| Scheme III: 60% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 40% Spores | |||

| 0.48 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 1.6 mg/mL spores | 2.39 (2.00–2.72) | 289 | Synergistic |

| 0.96 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 3.2 mg/mL spores | |||

| 1.44 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 4.8 mg/mL spores | |||

| 1.92 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 6.4 mg/mL spores | |||

| 2.40 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 8.0 mg/mL spores | |||

| Scheme IV: 80% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 20% Spores | |||

| 0.64 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 0.8 mg/mL spores | 1.47 (1.24–1.67) | 713 | Synergistic |

| 1.28 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 1.6 mg/mL spores | |||

| 1.92 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 2.4 mg/mL spores | |||

| 2.56 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 3.2 mg/mL spores | |||

| 3.20 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 4.0 mg/mL spores | |||

| Treatments | Post-Exposure Duration | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h 1 | 72 h 1 | 120 h 1 | |

| 1-Chlorooctadecane | (%) | (%) | (%) |

| 0.8 mg/mL | 13.35 ± 0.55p | 32.18 ± 0.34m | 46.03 ± 0.80g |

| 1.6 mg/mL | 20.32 ± 1.02lm | 35.56 ± 0.49l | 39.59 ± 0.88i |

| 2.4 mg/mL | 21.17 ± 1.03kl | 40.09 ± 0.69ij | 23.27 ± 0.44l |

| 3.2 mg/mL | 24.38 ± 1.18hi | 46.16 ± 0.97g | 17.13 ± 0.34op |

| 4.0 mg/mL | 27.14 ± 1.32fg | 52.86 ± 0.92d | 15.14 ± 0.25q |

| Scheme I: 20% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 80% Spores | |||

| 0.16 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 3.2 mg/mL spores | 15.04 ± 0.21op | 31.52 ± 0.37m | 60.78 ± 0.94b |

| 0.32 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 6.4 mg/mL spores | 16.38 ± 0.24no | 39.64 ± 0.59j | 53.88 ± 0.98e |

| 0.48 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 9.6 mg/mL spores | 20.22 ± 0.54lm | 44.17 ± 0.72gh | 56.42 ± 0.93d |

| 0.64 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 12.8 mg/mL spores | 21.19 ± 0.78kl | 50.11 ± 0.95ef | 52.78 ± 0.95e |

| 0.80 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 16.0 mg/mL spores | 25.15 ± 0.92ghi | 43.11 ± 0.84h | 41.46 ± 0.76h |

| Scheme II: 40% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 60% Spores | |||

| 0.32 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 2.4 mg/mL spores | 20.32 ± 0.31lm | 35.30 ± 0.55l | 40.03 ± 0.64hi |

| 0.64 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 4.8 mg/mL spores | 22.06 ± 0.70jkl | 36.50 ± 0.57l | 29.74 ± 0.55j |

| 0.96 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 7.2 mg/mL spores | 27.15 ± 0.72fg | 39.68 ± 0.78j | 24.09 ± 0.50l |

| 1.28 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 9.6 mg/mL spores | 30.01 ± 0.90de | 48.45 ± 0.91f | 20.10 ± 0.24m |

| 1.60 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 12 mg/mL spores | 34.18 ± 0.92bc | 52.93 ± 0.93d | 15.20 ± 0.20q |

| Scheme III: 60% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 40% Spores | |||

| 0.48 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 1.6 mg/mL spores | 20.10 ± 0.24lm | 35.69 ± 0.46l | 26.54 ± 0.72k |

| 0.96 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 3.2 mg/mL spores | 24.19 ± 0.60hij | 37.43 ± 0.56kl | 24.19 ± 0.60l |

| 1.44 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 4.8 mg/mL spores | 29.12 ± 0.78ef | 42.02 ± 0.70hi | 20.29 ± 0.39m |

| 1.92 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 6.4 mg/mL spores | 32.22 ± 0.87cd | 55.90 ± 0.76c | 17.44 ± 0.32no |

| 2.40 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 8.0 mg/mL spores | 33.22 ± 0.90bc | 63.85 ± 0.93b | 09.79 ± 0.26r |

| Scheme IV: 80% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 20% Spores | |||

| 0.64 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 0.8 mg/mL spores | 23.08 ± 0.57ijk | 38.92 ± 0.57jk | 15.58 ± 0.28pq |

| 1.28 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 1.6 mg/mL spores | 29.37 ± 0.64ef | 43.35 ± 0.69h | 09.67 ± 0.25r |

| 1.92 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 2.4 mg/mL spores | 33.02 ± 0.81bc | 50.16 ± 0.79ef | 03.58 ± 0.24s |

| 2.56 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 3.2 mg/mL spores | 35.12 ± 0.93b | 63.96 ± 0.91b | 01.79 ± 0.15t |

| 3.20 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 4.0 mg/mL spores | 39.32 ± 1.22a | 71.64 ± 1.05a | 01.24 ± 0.13t |

| M. anisopliae EBCL02049 spores | |||

| 4 mg/mL | 15.34 ± 0.43op | 49.13 ± 0.81f | 58.19 ± 0.81c |

| 8 mg/mL | 18.27 ± 0.56mn | 57.16 ± 0.98c | 63.83 ± 0.77a |

| 12 mg/mL | 21.08 ± 0.78kl | 51.35 ± 0.97de | 48.38 ± 0.97f |

| 16 mg/mL | 23.26 ± 0.88ijk | 43.67 ± 0.93h | 28.07 ± 0.62jk |

| 20 mg/mL | 26.17 ± 0.91gh | 36.26 ± 0.68l | 19.13 ± 0.60mn |

| Treatments | Post-Exposure Duration | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h 1 | 72 h 1 | 120 h 1 | |

| 1-Chlorooctadecane | (%) | (%) | (%) |

| 0.8 mg/mL | 12.89 ± 0.53kl | 30.38 ± 0.85q | 66.27 ± 1.19bc |

| 1.6 mg/mL | 20.42 ± 0.78h | 36.15 ± 0.90op | 57.13 ± 1.21d |

| 2.4 mg/mL | 21.20 ± 0.87h | 43.85 ± 0.93l | 37.31 ± 0.65h |

| 3.2 mg/mL | 26.87 ± 1.05d | 54.04 ± 1.27g | 31.36 ± 0.45ij |

| 4.0 mg/mL | 29.65 ± 1.29c | 66.10 ± 1.35c | 19.77 ± 0.36lm |

| Scheme I: 20% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 80% Spores | |||

| 0.16 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 3.2 mg/mL spores | 11.17 ± 0.27l | 53.13 ± 0.97gh | 76.13 ± 1.01a |

| 0.32 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 6.4 mg/mL spores | 13.33 ± 0.42k | 61.18 ± 0.99e | 68.07 ± 0.98b |

| 0.48 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 9.6 mg/mL spores | 18.13 ± 0.50j | 52.54 ± 1.04gh | 57.30 ± 1.11d |

| 0.64 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 12.8 mg/mL spores | 20.11 ± 0.76hi | 46.57 ± 0.95j | 40.43 ± 0.69g |

| 0.80 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 16.0 mg/mL spores | 21.32 ± 0.85gh | 29.46 ± 0.50q | 25.30 ± 0.58k |

| Scheme II: 40% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 60% Spores | |||

| 0.32 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 2.4 mg/mL spores | 14.17 ± 0.61k | 37.27 ± 0.61o | 43.08 ± 0.82f |

| 0.64 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 4.8 mg/mL spores | 21.20 ± 0.63h | 49.65 ± 0.81i | 44.12 ± 0.96f |

| 0.96 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 7.2 mg/mL spores | 25.42 ± 0.91de | 58.40 ± 1.18f | 39.80 ± 0.88g |

| 1.28 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 9.6 mg/mL spores | 27.07 ± 0.93d | 61.44 ± 1.20e | 25.46 ± 0.51k |

| 1.60 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 12.0 mg/mL spores | 30.11 ± 1.02c | 64.55 ± 1.25cd | 21.42 ± 0.50l |

| Scheme III: 60% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 40% Spores | |||

| 0.48 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 1.6 mg/mL spores | 17.21 ± 0.39j | 41.14 ± 0.77mn | 36.26 ± 0.68h |

| 0.96 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 3.2 mg/mL spores | 23.10 ± 0.65fg | 44.39 ± 0.85kl | 29.32 ± 0.63j |

| 1.44 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 4.8 mg/mL spores | 24.27 ± 0.70ef | 54.25 ± 1.03g | 25.37 ± 0.53k |

| 1.92 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 6.4 mg/mL spores | 29.22 ± 0.95c | 63.76 ± 1.24d | 20.54 ± 0.43l |

| 2.40 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 8.0 mg/mL spores | 34.20 ± 1.02a | 72.26 ± 1.25b | 16.28 ± 0.25n |

| Scheme IV: 80% 1-Chlorooctadecane: 20% Spores | |||

| 0.64 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 0.8 mg/mL spores | 23.38 ± 0.52f | 43.15 ± 0.81lm | 32.41 ± 0.52i |

| 1.28 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 1.6 mg/mL spores | 25.32 ± 0.70de | 53.19 ± 0.91gh | 26.42 ± 0.43k |

| 1.92 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 2.4 mg/mL spores | 26.19 ± 0.98d | 60.45 ± 0.99ef | 21.24 ± 0.37l |

| 2.56 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 3.2 mg/mL spores | 32.34 ± 1.12b | 66.23 ± 1.10c | 18.03 ± 0.52mn |

| 3.20 mg/mL 1-Chlorooctadecane + 4.0 mg/mL spores | 35.41 ± 1.18a | 81.28 ± 1.26a | 11.80 ± 0.37o |

| M. anisopliae EBCL02049 spores | |||

| 4 mg/mL | 09.28 ± 0.34m | 34.20 ± 0.79p | 56.53 ± 0.93d |

| 8 mg/mL | 17.11 ± 0.48j | 40.14 ± 0.88n | 65.87 ± 1.03c |

| 12 mg/mL | 18.41 ± 0.58ij | 46.43 ± 0.92jk | 54.14 ± 0.97e |

| 16 mg/mL | 20.13 ± 0.66hi | 51.24 ± 0.98hi | 43.75 ± 0.99f |

| 20 mg/mL | 23.16 ± 0.89fg | 60.24 ± 1.14ef | 25.46 ± 0.72k |

| 1-Chlorooctadecane (mg/mL) | Interaction Schemes | M. anisopliae (mg/mL) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme I | Scheme II | Scheme III | Scheme IV | ||||||

| 1-Chlorooctadecane (20%): Spores (80%) | 1-Chlorooctadecane (40%): Spores (60%) | 1-Chlorooctadecane (60%): Spores (40%) | 1-Chlorooctadecane (80%): Spores (20%) | ||||||

| Toxin mg/mL | Spores mg/mL | Toxin mg/mL | Spores mg/mL | Toxin mg/mL | Spores mg/mL | Toxin mg/mL | Spores mg/mL | ||

| 0.8 | 0.16 | 3.2 | 0.32 | 2.4 | 0.48 | 1.6 | 0.64 | 0.8 | 4 |

| 1.6 | 0.32 | 6.4 | 0.64 | 4.8 | 0.96 | 3.2 | 1.28 | 1.6 | 8 |

| 2.4 | 0.48 | 9.6 | 0.96 | 7.2 | 1.44 | 4.8 | 1.92 | 2.4 | 12 |

| 3.2 | 0.64 | 12.8 | 1.28 | 9.6 | 1.92 | 6.4 | 2.56 | 3.2 | 16 |

| 4 | 0.8 | 16 | 1.6 | 12 | 2.4 | 8 | 3.2 | 4 | 20 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hussain, A.; AlJabr, A.M. Potential Synergy between Spores of Metarhizium anisopliae and Plant Secondary Metabolite, 1-Chlorooctadecane for Effective Natural Acaricide Development. Molecules 2020, 25, 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25081900

Hussain A, AlJabr AM. Potential Synergy between Spores of Metarhizium anisopliae and Plant Secondary Metabolite, 1-Chlorooctadecane for Effective Natural Acaricide Development. Molecules. 2020; 25(8):1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25081900

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussain, Abid, and Ahmed Mohammed AlJabr. 2020. "Potential Synergy between Spores of Metarhizium anisopliae and Plant Secondary Metabolite, 1-Chlorooctadecane for Effective Natural Acaricide Development" Molecules 25, no. 8: 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25081900

APA StyleHussain, A., & AlJabr, A. M. (2020). Potential Synergy between Spores of Metarhizium anisopliae and Plant Secondary Metabolite, 1-Chlorooctadecane for Effective Natural Acaricide Development. Molecules, 25(8), 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25081900