2.1. Structural Characterization of Lait-X

Figure 1 shows the FTIR spectra of Lait-X oligomers and Lait-X bulk after curing to confirm the formation of the crosslink network. The peaks at 1755 and 1455 cm

−1 correspond to C=O stretching and C–H bending. The peaks at 1195, 1133, and 1094 cm

−1 are attributed to C–O–C stretching, and C–H bending is indicated by peaks at 950 cm

−1. The peak at 1638 cm

−1 represents C=C stretching, which confirmed the formation of the crosslink network and the completion of curing in Lait-X oligomers.

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra of Lait-X bulk and Lait-X oligomers.

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra of Lait-X bulk and Lait-X oligomers.

Figure 2 shows the Wide-Angle X-ray Diffraction (WAXD) profiles of Lait-X oligomers and Lait-X bulk (without pore structure) to analyze the crystal structures. Both samples had a shallow broad peak at 2θ = 18.3° with a correlation length of about 0.49 nm. Both samples were determined to be amorphous in nature with Lait-X having a crosslinked structure. The thermal behavior of Lait-X bulk was investigated by temperature-modulated DSC (TMDSC) (

Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Wide-Angle X-ray Diffraction (WAXD) patterns of Lait-X oligomers and Lait-X bulk.

Figure 2.

Wide-Angle X-ray Diffraction (WAXD) patterns of Lait-X oligomers and Lait-X bulk.

Figure 3.

temperature-modulated DSC (TMDSC) scans of Lait-X oligomers and Lait-X bulk with different concentrations of initiator. For cured Lait-X, the content of the initiator is shown.

Figure 3.

temperature-modulated DSC (TMDSC) scans of Lait-X oligomers and Lait-X bulk with different concentrations of initiator. For cured Lait-X, the content of the initiator is shown.

The Lait-X oligomers had a

Tg of −15.4 °C and the Lait-X bulk had a

Tg of 32.2 and 28.5 °C when 1 and 5 wt % was used for curing. There are no melting points (

Tm) in the thermograms, which demonstrates that the Lait-X bulk samples were amorphous and thermoset. Also, as the initiator concentration was increased from 1 to 5 wt %, the

Tg showed a decrease. The initiator to resin ratio of 1 wt % was used throughout the subsequent enzymatic degradation studies on the porous structures based on Lait-X. The

Tg of the linear bulk PLA sample, designated amorphous linear PLA (χ

c = 0%), was 58 °C. Additionally, the density of Lait-X bulk was 1.246 g/cm

3 and for linear PLA bulk it was 1.262 g/cm

3 (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Morphological properties of linear and crosslinked polylactide (PLA) porous structures.

Table 1.

Morphological properties of linear and crosslinked polylactide (PLA) porous structures.

| Parameters | Linear PLA Nanoporous | Linear PLA Microporous | Lait-X Porous |

|---|

| ρ/g·cm−3 | 1.012 | 0.325 | 0.841 |

| average diameter/µm | 0.016 | 0.418 | 0.153 |

| Np × 10−8/cell·cm−3 | 38,300 | 3.81 | 15,462 |

| δ/µm | 0.23 | 1.55 | 0.08 |

| bulk density/g·cm−3 | 1.262 | 1.262 | 1.246 |

| total pore area/m2·g−1 | 53.7 | 24.5 | 13.4 |

| Porosity (a)/% | 22.8 | 76.4 | 43.0 |

2.2. Morphological Properties

The morphological parameters of the thermoset and thermoplastic PLA porous structures are summarized in

Table 1.

Figure 4 shows the pore size distribution of Lait-X and linear PLA samples with nanocellular and microcellular pores measured through Hg porosimetry. The pores of Lait-X were created via the salt leaching method and linear PLA via batch foam processing through supercritical CO

2.

Figure 4.

Pore size distribution of (a) Lait-X having a porous structure; (b) linear polylactide (PLA) having a nanoporous structure; and (c) linear PLA having a microporous structure before degradation.

Figure 4.

Pore size distribution of (a) Lait-X having a porous structure; (b) linear polylactide (PLA) having a nanoporous structure; and (c) linear PLA having a microporous structure before degradation.

The average pore diameters of Lait-X porous, linear PLA nanoporous, and linear PLA microporous structures were 0.153, 0.016, and 0.418 µm, respectively; porosity (%) of 43.0, 22.8, and 76.4. The density (ρ) was 0.84, 1.01, and 0.32 g·cm

−3, respectively. The pore density (

Np) in Lait-X porous, linear PLA nanoporous, and linear PLA microporous structures were 15,462 × 10

8, 38,300 × 10

8, and 3.81 × 10

8 cell·cm

−3. The pore wall thickness of the porous walls (δ) of Lait-X porous (0.08 µm), linear PLA nanoporous (0.23 µm), and linear PLA microporous (1.55 µm) structures showed a significant variation, with Lait-X having the lowest thickness. This may be due to the difference in the preparation methods of the porous structures of Lait-X and linear PLA. The SEM images of the Lait-X porous, linear PLA microporous, and linear PLA nanoporous samples are given in

Section 2.3. The Lait-X porous structure had well connected pores of varying diameters. The macroporous structures with the linear PLA had well distributed pores with thick pore walls of PLA matrix and the nanoporous ones had thin pore walls with better pore distribution than the former.

2.3. Enzymatic Degradation

Figure 5 represents the time variation of weight loss (%) with the enzymatic degradation of the Lait-X bulk sample for 250 h. The specific surface area to volume ratio (

A/

V) of the sample was 1.5/mm

−1. It is clear from the figure that weight loss increased linearly with time. This may be due to the disintegration of the crosslinked chains due to the low

Tg (~32 °C) that matches to the enzyme medium temperature through biodegradation. The time variation of weight loss (%) with the enzymatic degradation of the linear PLA bulk sample for different dimensions,

i.e.,

A/

V ratios of 2.6, 5.4, and 11.4 mm

−1, is give in

Figure 6. When the

A/

V value is large (11.4 mm

−1), the degradation is faster due to the increased interaction of the enzyme with the surface, which leads to fast degradation as compared to the lower value (2.6 mm

−1). The degradation rate for Lait-X bulk and linear PLA samples were derived from the slopes in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The degradation rate of Lait-X bulk was faster than the linear PLA bulk with the same

A/

V value (

Figure 7). That is, the thermoset PLA has much free volume at 37 °C, because it reaches glass transition. When the degree of crystallinity of the linear PLA was near to 50%, the degradation rate was too slow, almost 4.5 times slower than its counterpart with zero crystallinity. The linear PLA having χ

c = 50% was prepared by isothermal annealing at 100 °C for 20 min [

15]. Thus it is clear that the enzymatic breakdown of the amorphous chains in PLA is faster than in the crystalline counterpart.

Figure 5.

Normalized weight loss of Lait-X bulk. The solid line was calculated by linear regression.

Figure 5.

Normalized weight loss of Lait-X bulk. The solid line was calculated by linear regression.

Figure 6.

Normalized weight loss of linear polylactide (PLA) having different dimensions. The solid line was calculated by linear regression.

Figure 6.

Normalized weight loss of linear polylactide (PLA) having different dimensions. The solid line was calculated by linear regression.

Figure 7.

The degradation rate of linear polylactide (PLA) and Lait-X bulk. The linear PLA having χ

c = 50% was prepared by isothermally annealing at 100 °C for 20 min [

15].

Figure 7.

The degradation rate of linear polylactide (PLA) and Lait-X bulk. The linear PLA having χ

c = 50% was prepared by isothermally annealing at 100 °C for 20 min [

15].

The water uptake of Lait-X bulk (

A/

V = 1.5 mm

−1) and linear PLA bulk (

A/

V = 2.6 mm

−1), analyzed against the degradation time, is given in

Figure 8. Lait-X bulk absorbed showed nearly 60% water uptake, whereas for the linear PLA bulk, this was less than 5%. The Lait-X bulk showed significant swelling due to the crosslinked network, which led to an increased absorption. This has a significant impact on enzymatic degradation. The necessary conditions that make enzymatic reactions faster on a substrate are the temperature (37 °C) and the presence of water, which very well suites the Lait-X bulk sample.

Figure 8.

Water absorption changes of Lait-X bulk (A/V = 1.5 mm−1) and linear polylactide (PLA) (A/V = 2.6 mm−1) during the enzymatic degradation at 37 °C.

Figure 8.

Water absorption changes of Lait-X bulk (A/V = 1.5 mm−1) and linear polylactide (PLA) (A/V = 2.6 mm−1) during the enzymatic degradation at 37 °C.

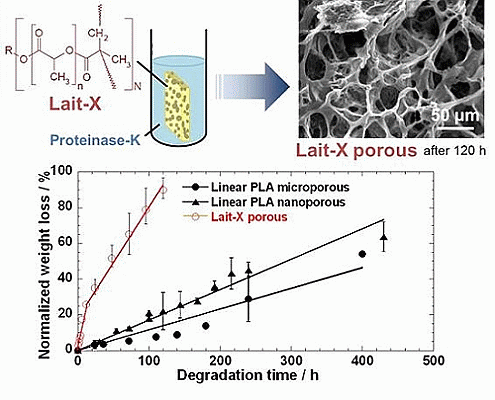

The time variation of weight loss (%) with the enzymatic degradation of the Lait-X porous, linear PLA microporous, and linear PLA nanoporous samples for 250 h are shown in

Figure 9. The degradation was in the order Lait-X porous > linear PLA nanoporous > linear PLA microporous with values of 2.2 × 10

−2, 0.18 × 10

−2, and 0.10 × 10

−2 h

−1, respectively, and

A/

V values of 1.1 × 10

4, 5.4 × 10

4, and 0.78 × 10

4 mm

−1 (

Table 2). The

A/

V values were calculated from the parameters listed in

Table 1 [

15].

Figure 9.

Normalized weight loss of linear polylactide (PLA) having nanoporous and microporous structures, and Lait-X having a porous structure.

Figure 9.

Normalized weight loss of linear polylactide (PLA) having nanoporous and microporous structures, and Lait-X having a porous structure.

Table 2.

Surface area to volume ratio (

A/

V) and degradation rate obtained from the initial slope in

Figure 9.

Table 2.

Surface area to volume ratio (A/V) and degradation rate obtained from the initial slope in Figure 9.

| Samples | A/V (a) × 10−4/mm−1 | Degradation Rate × 102/h−1 |

|---|

| Lait-X porous | 1.10 | 2.20 |

| Linear PLA nanoporous | 5.40 | 0.18 |

| Linear PLA microporous | 0.78 | 0.10 |

The Lait-X porous sample showed a higher mass loss similar to bulk (

Figure 9) due to the crosslinked structure with low

Tg. The linear PLA nanoporous sample showed a higher degradation than the microporous. This was due to a larger area of exposure for interaction with the enzyme (

A/

V of 5.4 × 10

−4 versus 0.78 × 10

−4 mm

−1). The water intake of Lait-X porous, linear PLA microporous and linear PLA nanoporous samples is shown in

Figure 10. The content of absorbed water greatly determines the enzymatic degradability. The water intake of the Lait-X porous structure was significantly faster than for the linear porous ones. The Lait-X porous samples reached the saturation value at around 150 h of immersion, with nearly 150% of water absorption. This is very similar to the water absorption level of hydrophilic gels. This may be attributed to the crosslinked structure, which leads to swelling in water and thus the higher water uptake. During the first 250 h, the water absorption of the linear PLA porous structures increased continuously to 30% for PLA microporous and 50% for PLA nanoporous samples. Beyond 300 h, the water uptake remained almost constant, presumably due to the saturation caused by the morphology development after enzymatic degradation. The nanoporous sample takes up larger amounts of water compared with the microporous sample. The absorbed water facilitates the enzymatic degradation of matrix linear PLA.

Figure 10.

Water absorption changes of linear polylactide (PLA) having nanoporous and microporous structures, and Lait-X having a porous structure during enzymatic degradation at 37 °C.

Figure 10.

Water absorption changes of linear polylactide (PLA) having nanoporous and microporous structures, and Lait-X having a porous structure during enzymatic degradation at 37 °C.

Figure 11 shows the surface and the cross-section morphologies of Lait-X bulk and linear PLA bulk, through SEM imaging, before and after enzymatic degradation. The surface and the cross section of Lait-X and the surface of linear PLA bulk samples are smooth before degradation (

Figure 11a,c,e). After degradation up to 240 h, many pores are generated on the surface of the bulk samples and the pores are spherical in shape with circular interconnections (

Figure 11d,f). This kind of connected spherical-pore structures are due to the breakdown of swollen (amorphous) regions by the enzymatic degradation, as reported previously [

16,

17,

18].

Figure 11.

Typical SEM images of the surface and the cross section of Lait-X bulk (a,b) (surface); Lait-X bulk (c,d) (cross section); and linear polylactide (PLA) bulk (e,f) (surface) before and after enzymatic degradation for 240 h.

Figure 11.

Typical SEM images of the surface and the cross section of Lait-X bulk (a,b) (surface); Lait-X bulk (c,d) (cross section); and linear polylactide (PLA) bulk (e,f) (surface) before and after enzymatic degradation for 240 h.

The morphology of the Lait-X porous and linear PLA porous structures in the micro and nanoporous range is given in

Figure 12. The Lait-X porous structure showed a rapid loss of features (

Figure 12a,b) after 120 h of exposure to the enzymatic degradation due to the higher affinity for water that leads to enhanced activity, as discussed earlier.

Figure 12.

Typical SEM images of the cross section of Lait-X having porous structure (a,b), linear PLA having nanoporous structure (c,d) and linear PLA having microporous structure (e,f) before and after degradation for different time intervals.

Figure 12.

Typical SEM images of the cross section of Lait-X having porous structure (a,b), linear PLA having nanoporous structure (c,d) and linear PLA having microporous structure (e,f) before and after degradation for different time intervals.

Figure 12d presents the morphological change of the cross section in the PLA nanoporous sample having χ

c = 55% after enzymatic degradation for 240 h (corresponding to 45 wt % degradation).

For the linear PLA nanoporous structure (

Figure 12d) there is a great tendency to generate the skin-layer (~50 µm thickness) with a cracked surface and hence more rapid fragmentation on the surface, as in

Figure 11b. No significant change, such as pore formation, on the surface during degradation up to 240 h suggests that the core part of the foam underwent significant hydrolysis during this period. This indicates that the pore structure allows the PLA chains to become susceptible to enzymatic hydrolysis. This speculation is supported by the water uptake behavior of the PLA nanoporous sample as compared to the microporous ones. Another interesting feature of the nanoporous structure is the formation of some flower-like structures as a remaining sample in the core part, reflecting the spherulite of the crystallized PLA matrix during foaming [

15].

Figure 12e shows the cross section morphologies of the PLA microporous structure with χ

c = 16.9% and the sample recovered after enzymatic degradation for 400 h (

Figure 12f) (corresponding to 28 wt % degradation), regardless of χ

c in the matrix of the microporous samples. Many pores appeared on the surface after degradation for 400 h, and those with diameters of ~15 µm were shaped in a polygon cell structure. Interestingly, in the cross section, the fibrillar structures with diameters of ~1–2 µm were generated on the thick pore wall (δ ~ 1.6 µm), with some entanglement, suggesting that the amorphous region in the pore wall had been predominantly degraded. This structure was enhanced, as the degradation took place.