Mechanisms Underlying the Anti-Aging and Anti-Tumor Effects of Lithocholic Bile Acid

Abstract

:1. Introduction

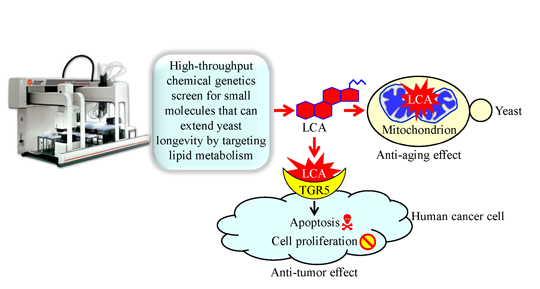

2. Bile Acids Extend Healthy Lifespan in Multicellular Eukaryotic Organisms across Species

3. A Mechanism Underlying the Longevity-Extending Effect of LCA (Lithocholic Acid) in Chronologically Aging Yeast

4. A Hypothesis: The Mitochondria-Centered Mechanism by Which LCA Prolongs Longevity Could Be Integrated into a Network of Interorganellar Communications Underlying Cellular Aging

5. A Mechanism Underlying an Anti-Tumor Effect of LCA in Cultured Human Cancer Cells

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guarente, L.P.; Partridge, L.; Wallace, D.C. Molecular Biology of Aging; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2008; p. 610. [Google Scholar]

- Masoro, E.J.; Austad, S.N. Handbook of the Biology of Aging, 7th ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Oxford, UK, 2011; p. 572. [Google Scholar]

- Niccoli, T.; Partridge, L. Ageing as a risk factor for disease. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, R741–R752. [Google Scholar]

- Gems, D.; Partridge, L. Genetics of longevity in model organisms: Debates and paradigm shifts. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013, 75, 621–644. [Google Scholar]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, L.; Partridge, L.; Longo, V.D. Extending healthy life span—From yeast to humans. Science 2010, 328, 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein, M. Lessons on longevity from budding yeast. Nature 2010, 464, 513–519. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, C.J. The genetics of ageing. Nature 2010, 464, 504–512. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, V.D.; Shadel, G.S.; Kaeberlein, M.; Kennedy, B. Replicative and chronological aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Leonov, A.; Titorenko, V.I. A network of interorganellar communications underlies cellular aging. IUBMB Life 2013, 65, 665–674. [Google Scholar]

- Arlia-Ciommo, A.; Leonov, A.; Piano, A.; Svistkova, V.; Titorenko, V.I. Cell-autonomous mechanisms of chronological aging in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbial Cell 2014, 1, 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, E.L.; Brunet, A. Signaling networks in aging. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 407–412. [Google Scholar]

- Finley, L.W.; Haigis, M.C. The coordination of nuclear and mitochondrial communication during aging and calorie restriction. Ageing Res. Rev. 2009, 8, 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, A.A.; Bourque, S.D.; Kyryakov, P.; Boukh-Viner, T.; Gregg, C.; Beach, A.; Burstein, M.T.; Machkalyan, G.; Richard, V.; Rampersad, S.; et al. A novel function of lipid droplets in regulating longevity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009, 37, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, A.A.; Bourque, S.D.; Kyryakov, P.; Gregg, C.; Boukh-Viner, T.; Beach, A.; Burstein, M.T.; Machkalyan, G.; Richard, V.; Rampersad, S.; et al. Effect of calorie restriction on the metabolic history of chronologically aging yeast. Exp. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 555–571. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, A.; Titorenko, V.I. In search of housekeeping pathways that regulate longevity. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 3042–3044. [Google Scholar]

- Titorenko, V.I.; Terlecky, S.R. Peroxisome metabolism and cellular aging. Traffic 2011, 12, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, A.; Burstein, M.T.; Richard, V.R.; Leonov, A.; Levy, S.; Titorenko, V.I. Integration of peroxisomes into an endomembrane system that governs cellular aging. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyryakov, P.; Beach, A.; Richard, V.R.; Burstein, M.T.; Leonov, A.; Levy, S.; Titorenko, V.I. Caloric restriction extends yeast chronological lifespan by altering a pattern of age-related changes in trehalose concentration. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Vatner, D.E.; O’Connor, J.P.; Ivessa, A.; Ge, H.; Chen, W.; Hirotani, S.; Ishikawa, Y.; Sadoshima, J.; Vatner, S.F. Type 5 adenylyl cyclase disruption increases longevity and protects against stress. Cell 2007, 130, 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Enns, L.C.; Ladiges, W. Protein kinase A signaling as an anti-aging target. Ageing Res. Rev. 2010, 9, 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Enns, L.C.; Morton, J.F.; Mangalindan, R.S.; McKnight, G.S.; Schwartz, M.W.; Kaeberlein, M.R.; Kennedy, B.K.; Rabinovitch, P.S.; Ladiges, W.C. Attenuation of age-related metabolic dysfunction in mice with a targeted disruption of the Cβ subunit of protein kinase A. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009, 64, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Enns, L.C.; Morton, J.F.; Treuting, P.R.; Emond, M.J.; Wolf, N.S.; Dai, D.F.; McKnight, G.S.; Rabinovitch, P.S.; Ladiges, W.C. Disruption of protein kinase A in mice enhances healthy aging. PLoS One 2009, 4, e5963. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan, S.D.; Yen, K.; Tissenbaum, H.A. Converging pathways in lifespan regulation. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, R657–R666. [Google Scholar]

- Zoncu, R.; Efeyan, A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR: From growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hardie, D.G.; Ross, F.A.; Hawley, S.A. AMPK: A nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Inoki, K.; Kim, J.; Guan, K.L. AMPK and mTOR in cellular energy homeostasis and drug targets. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012, 52, 381–400. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, L.R.; Hansen, M. Lessons from C. elegans: Signaling pathways for longevity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 23, 637–644. [Google Scholar]

- Laplante, M.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 2012, 149, 274–293. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Park, J.Y.; Dillinger, J.G.; de Lorenzo, M.S.; Yuan, C.; Lai, L.; Wang, C.; Ho, D.; Tian, B.; Stanley, W.C.; et al. Common mechanisms for calorie restriction and adenylyl cyclase type 5 knockout models of longevity. Aging Cell 2012, 11, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Cornu, M.; Albert, V.; Hall, M.N. mTOR in aging, metabolism, and cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2013, 23, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jewell, J.L.; Guan, K.L. Nutrient signaling to mTOR and cell growth. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013, 38, 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Vatner, S.F.; Park, M.; Yan, L.; Lee, G.J.; Lai, L.; Iwatsubo, K.; Ishikawa, Y.; Pessin, J.; Vatner, D.E. Adenylyl cyclase type 5 in cardiac disease, metabolism, and aging. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013, 305, H1–H8. [Google Scholar]

- Burkewitz, K.; Zhang, Y.; Mair, W.B. AMPK at the nexus of energetics and aging. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F.; Liu, F. Targeting tissue-specific metabolic signaling pathways in aging: The promise and limitations. Protein Cell 2014, 5, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.S.; Kapahi, P.; Hsueh, W.C.; Kockel, L. TOR signaling never gets old: Aging, longevity and TORC1 activity. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Mercken, E.M.; Carboneau, B.A.; Krzysik-Walker, S.M.; de Cabo, R. Of mice and men: The benefits of caloric restriction, exercise, and mimetics. Ageing Res. Rev. 2012, 11, 390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein, M. Longevity and aging. F1000Prime Rep. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeberlein, M. mTOR inhibition: From aging to autism and beyond. Scientifica 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cabo, R.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Bernier, M.; Hall, M.N.; Madeo, F. The search for antiaging interventions: From elixirs to fasting regimens. Cell 2014, 157, 1515–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Weindruch, R.; Walford, R.L. The Retardation of Aging and Disease by Dietary Restriction; Charles C. Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Masoro, E.J. Caloric Restriction: A Key to Understanding and Modulating Aging, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Oxford, UK, 2002; p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Min, K.J.; Flatt, T.; Kulaots, I.; Tatar, M. Counting calories in Drosophila diet restriction. Exp. Gerontol. 2007, 42, 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, W.; Dillin, A. Aging and survival: The genetics of life span extension by dietary restriction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 727–754. [Google Scholar]

- Colman, R.J.; Anderson, R.M.; Johnson, S.C.; Kastman, E.K.; Kosmatka, K.J.; Beasley, T.M.; Allison, D.B.; Cruzen, C.; Simmons, H.A.; Kemnitz, J.W.; et al. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science 2009, 325, 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.M.; Weindruch, R. Metabolic reprogramming, caloric restriction and aging. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 21, 134–141. [Google Scholar]

- Speakman, J.R.; Mitchell, S.E. Caloric restriction. Mol. Aspects Med. 2011, 32, 159–221. [Google Scholar]

- Mattison, J.A.; Roth, G.S.; Beasley, T.M.; Tilmont, E.M.; Handy, A.M.; Herbert, R.L.; Longo, D.L.; Allison, D.B.; Young, J.E.; Bryant, M.; et al. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Nature 2012, 489, 318–321. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.W.; Kim, D.H.; Park, M.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, N.D.; Lee, J.; Yu, B.P.; Chung, H.Y. Recent advances in calorie restriction research on aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Guarente, L. Calorie restriction and sirtuins revisited. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 2072–2085. [Google Scholar]

- Libert, S.; Guarente, L. Metabolic and neuropsychiatric effects of calorie restriction and sirtuins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013, 75, 669–684. [Google Scholar]

- Willcox, B.J.; Willcox, D.C. Caloric restriction, caloric restriction mimetics, and healthy aging in Okinawa: Controversies and clinical implications. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2014, 17, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.A.; Buehner, G.; Chang, Y.; Harper, J.M.; Sigler, R.; Smith-Wheelock, M. Methionine-deficient diet extends mouse lifespan, slows immune and lens aging, alters glucose, T4, IGF-I and insulin levels, and increases hepatocyte MIF levels and stress resistance. Aging Cell 2005, 4, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Troen, A.M.; French, E.E.; Roberts, J.F.; Selhub, J.; Ordovas, J.M.; Parnell, L.D.; Lai, C.Q. Lifespan modification by glucose and methionine in Drosophila melanogaster fed a chemically defined diet. Age 2007, 29, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.P.; Simpson, S.J.; Clissold, F.J.; Brooks, R.; Ballard, J.W.; Taylor, P.W.; Soran, N.; Raubenheimer, D. Lifespan and reproduction in Drosophila: New insights from nutritional geometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2498–2503. [Google Scholar]

- Alvers, A.L.; Fishwick, L.K.; Wood, M.S.; Hu, D.; Chung, H.S.; Dunn, W.A., Jr.; Aris, J.P. Autophagy and amino acid homeostasis are required for chronological longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aging Cell 2009, 8, 353–369. [Google Scholar]

- Fanson, B.G.; Weldon, C.W.; Pérez-Staples, D.; Simpson, S.J.; Taylor, P.W. Nutrients, not caloric restriction, extend lifespan in Queensland fruit flies (Bactrocera tryoni). Aging Cell 2009, 8, 514–523. [Google Scholar]

- Flatt, T. Ageing: Diet and longevity in the balance. Nature 2009, 462, 989–990. [Google Scholar]

- Grandison, R.C.; Piper, M.D.; Partridge, L. Amino-acid imbalance explains extension of lifespan by dietary restriction in Drosophila. Nature 2009, 462, 1061–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, E.L.; Brunet, A. Different dietary restriction regimens extend lifespan by both independent and overlapping genetic pathways in C. elegans. Aging Cell 2009, 8, 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, M.D.; Partridge, L.; Raubenheimer, D.; Simpson, S.J. Dietary restriction and aging: A unifying perspective. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Tatar, M. The plate half-full: Status of research on the mechanisms of dietary restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Exp. Gerontol. 2011, 46, 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- Swindell, W.R. Dietary restriction in rats and mice: A meta-analysis and review of the evidence for genotype-dependent effects on lifespan. Ageing Res. Rev. 2012, 11, 254–270. [Google Scholar]

- Aris, J.P.; Alvers, A.L.; Ferraiuolo, R.A.; Fishwick, L.K.; Hanvivatpong, A.; Hu, D.; Kirlew, C.; Leonard, M.T.; Losin, K.J.; Marraffini, M.; et al. Autophagy and leucine promote chronological longevity and respiration proficiency during calorie restriction in yeast. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Cabreiro, F.; Au, C.; Leung, K.Y.; Vergara-Irigaray, N.; Cochemé, H.M.; Noori, T.; Weinkove, D.; Schuster, E.; Greene, N.D.; Gems, D. Metformin retards aging in C. elegans by altering microbial folate and methionine metabolism. Cell 2013, 153, 228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.Y.; Johnson, T.E.; Nelson, J.F. Genetic variation in responses to dietary restriction—an unbiased tool for hypothesis testing. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Roman, I.; Barja, G. Regulation of longevity and oxidative stress by nutritional interventions: Role of methionine restriction. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 1030–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, E.; MacNeil, L.T.; Arda, H.E.; Zhu, L.J.; Walhout, A.J. Integration of metabolic and gene regulatory networks modulates the C. elegans dietary response. Cell 2013, 153, 253–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Song, L.; Liu, S.Q.; Huang, D. Independent and additive effects of glutamic acid and methionine on yeast longevity. PLoS One 2013, 8, e79319. [Google Scholar]

- Ruckenstuhl, C.; Netzberger, C.; Entfellner, I.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Kickenweiz, T.; Stekovic, S.; Gleixner, C.; Schmid, C.; Klug, L.; Sorgo, A.G.; et al. Lifespan extension by methionine restriction requires autophagy-dependent vacuolar acidification. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004347. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, E.; MacNeil, L.T.; Ritter, A.D.; Yilmaz, L.S.; Rosebrock, A.P.; Caudy, A.A.; Walhout, A.J. Interspecies systems biology uncovers metabolites affecting C. elegans gene expression and life history traits. Cell 2014, 156, 759–770. [Google Scholar]

- Howitz, K.T.; Bitterman, K.J.; Cohen, H.Y.; Lamming, D.W.; Lavu, S.; Wood, J.G.; Zipkin, R.E.; Chung, P.; Kisielewski, A.; Zhang, L.L.; et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature 2003, 425, 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, J.H.; Goupil, S.; Garber, G.B.; Helfand, S.L. An accelerated assay for the identification of lifespan-extending interventions in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 12980–12985. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.G.; Rogina, B.; Lavu, S.; Howitz, K.; Helfand, S.L.; Tatar, M.; Sinclair, D. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature 2004, 430, 686–689. [Google Scholar]

- Baur, J.A.; Pearson, K.J.; Price, N.L.; Jamieson, H.A.; Lerin, C.; Kalra, A.; Prabhu, V.V.; Allard, J.S.; Lopez-Lluch, G.; Lewis, K.; et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature 2006, 444, 337–342. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, R.W., 3rd.; Kaeberlein, M.; Caldwell, S.D.; Kennedy, B.K.; Fields, S. Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzano, D.R.; Terzibasi, E.; Genade, T.; Cattaneo, A.; Domenici, L.; Cellerino, A. Resveratrol prolongs lifespan and retards the onset of age-related markers in a short-lived vertebrate. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 296–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz, N.D.; Chatenay-Lapointe, M.; Pan, Y.; Shadel, G.S. Reduced TOR signaling extends chronological life span via increased respiration and upregulation of mitochondrial gene expression. Cell Metab. 2007, 5, 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Medvedik, O.; Lamming, D.W.; Kim, K.D.; Sinclair, D.A. MSN2 and MSN4 link calorie restriction and TOR to sirtuin-mediated lifespan extension in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e261. [Google Scholar]

- Petrascheck, M.; Ye, X.; Buck, L.B. An antidepressant that extends lifespan in adult Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2007, 450, 553–556. [Google Scholar]

- Anisimov, V.N.; Berstein, L.M.; Egormin, P.A.; Piskunova, T.S.; Popovich, I.G.; Zabezhinski, M.A.; Tyndyk, M.L.; Yurova, M.V.; Kovalenko, I.G.; Poroshina, T.E.; et al. Metformin slows down aging and extends life span of female SHR mice. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 2769–2773. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti, M.G.; Foster, A.L.; Vantipalli, M.C.; White, M.P.; Sampayo, J.N.; Gill, M.S.; Olsen, A.; Lithgow, G.J. Compounds that confer thermal stress resistance and extended lifespan. Exp. Gerontol. 2008, 43, 882–891. [Google Scholar]

- McColl, G.; Killilea, D.W.; Hubbard, A.E.; Vantipalli, M.C.; Melov, S.; Lithgow, G.J. Pharmacogenetic analysis of lithium-induced delayed aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 350–357. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, K.J.; Baur, J.A.; Lewis, K.N.; Peshkin, L.; Price, N.L.; Labinskyy, N.; Swindell, W.R.; Kamara, D.; Minor, R.K.; Perez, E.; et al. Resveratrol delays age-related deterioration and mimics transcriptional aspects of dietary restriction without extending life span. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, N.; Mahlknecht, U. Aging and anti-aging: Unexpected side effects of everyday medication through sirtuin1 modulation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 21, 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Evason, K.; Collins, J.J.; Huang, C.; Hughes, S.; Kornfeld, K. Valproic acid extends Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan. Aging Cell 2008, 7, 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Wanke, V.; Cameroni, E.; Uotila, A.; Piccolis, M.; Urban, J.; Loewith, R.; de Virgilio, C. Caffeine extends yeast lifespan by targeting TORC1. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 69, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko, Z.N.; Blagosklonny, M.V. At concentrations that inhibit mTOR, resveratrol suppresses cellular senescence. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 1901–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko, Z.N.; Shtutman, M.; Blagosklonny, M.V. Pharmacologic inhibition of MEK and PI-3K converges on the mTOR/S6 pathway to decelerate cellular senescence. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 1896–1900. [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko, Z.N.; Zubova, S.G.; Bukreeva, E.I.; Pospelov, V.A.; Pospelova, T.V.; Blagosklonny, M.V. Rapamycin decelerates cellular senescence. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 1888–1895. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, T.; Knauer, H.; Schauer, A.; Büttner, S.; Ruckenstuhl, C.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Ring, J.; Schroeder, S.; Magnes, C.; Antonacci, L.; et al. Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, D.E.; Strong, R.; Sharp, Z.D.; Nelson, J.F.; Astle, C.M.; Flurkey, K.; Nadon, N.L.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Frenkel, K.; Carter, C.S.; et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 2009, 460, 392–395. [Google Scholar]

- Skulachev, V.P.; Anisimov, V.N.; Antonenko, Y.N.; Bakeeva, L.E.; Chernyak, B.V.; Erichev, V.P.; Filenko, O.F.; Kalinina, N.I.; Kapelko, V.I.; Kolosova, N.G.; et al. An attempt to prevent senescence: A mitochondrial approach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1787, 437–461. [Google Scholar]

- Bjedov, I.; Toivonen, J.M.; Kerr, F.; Slack, C.; Jacobson, J.; Foley, A.; Partridge, L. Mechanisms of life span extension by rapamycin in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 2010, 11, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, A.A.; Richard, V.R.; Kyryakov, P.; Bourque, S.D.; Beach, A.; Burstein, M.T.; Glebov, A.; Koupaki, O.; Boukh-Viner, T.; Gregg, C.; et al. Chemical genetic screen identifies lithocholic acid as an anti-aging compound that extends yeast chronological life span in a TOR-independent manner, by modulating housekeeping longevity assurance processes. Aging 2010, 2, 393–414. [Google Scholar]

- Onken, B.; Driscoll, M. Metformin induces a dietary restriction-like state and the oxidative stress response to extend C. elegans healthspan via AMPK, LKB1, and SKN-1. PLoS One 2010, 5, e8758. [Google Scholar]

- Baur, J.A.; Ungvari, Z.; Minor, R.K.; le Couteur, D.G.; de Cabo, R. Are sirtuins viable targets for improving healthspan and lifespan? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 443–461. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.H.; Manganiello, V.; Dyck, J.R. Resveratrol as a calorie restriction mimetic: Therapeutic implications. Trends Cell Biol. 2012, 22, 546–554. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, M.H.; Lai, C.S.; Tsai, M.L.; Wu, J.C.; Ho, C.T. Molecular mechanisms for anti-aging by natural dietary compounds. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 88–115. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.J.; Ahmad, F.; Philp, A.; Baar, K.; Williams, T.; Luo, H.; Ke, H.; Rehmann, H.; Taussig, R.; Brown, A.L.; et al. Resveratrol ameliorates aging-related metabolic phenotypes by inhibiting cAMP phosphodiesterases. Cell 2012, 148, 421–433. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Nishida, Y.; Wang, M.; Verdin, E. Metabolic regulation, mitochondria and the life-prolonging effect of rapamycin: A mini-review. Gerontology 2012, 58, 524–530. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wu, W.Y.; Jiang, B.H.; Yang, M.; Guo, D.A. Pharmacological tools for the development of traditional Chinese medicine. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 620–628. [Google Scholar]

- Rallis, C.; Codlin, S.; Bähler, J. TORC1 signaling inhibition by rapamycin and caffeine affect lifespan, global gene expression, and cell proliferation of fission yeast. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 563–573. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, J.; Franke, J.; Ehrenhofer-Murray, A.E. Chemical genetic screen in fission yeast reveals roles for vacuolar acidification, mitochondrial fission, and cellular GMP levels in lifespan extension. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 574–583. [Google Scholar]

- Rallis, C.; López-Maury, L.; Georgescu, T.; Pancaldi, V.; Bähler, J. Systematic screen for mutants resistant to TORC1 inhibition in fission yeast reveals genes involved in cellular ageing and growth. Biol. Open 2014, 3, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Song, L.; Liu, S.Q.; Huang, D. Tanshinones extend chronological lifespan in budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M.; Kahn, B.B.; Kahn, C.R. Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science 2003, 299, 572–574. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.H.; Lin, W.D.; Huang, S.Y.; Lee, Y.H. Effect of a C/EBP gene replacement on mitochondrial biogenesis in fat cells. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 1970–1975. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, F.; Kurtev, M.; Chung, N.; Topark-Ngarm, A.; Senawong, T.; Machado De Oliveira, R.; Leid, M.; McBurney, M.W.; Guarente, L. Sirt1 promotes fat mobilization in white adipocytes by repressing PPAR-γ. Nature 2004, 429, 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- Bordone, L.; Guarente, L. Calorie restriction, SIRT1 and metabolism: Understanding longevity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 298–305. [Google Scholar]

- Grönke, S.; Mildner, A.; Fellert, S.; Tennagels, N.; Petry, S.; Müller, G.; Jäckle, H.; Kühnlein, R.P. Brummer lipase is an evolutionary conserved fat storage regulator in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 2005, 1, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Haemmerle, G.; Lass, A.; Zimmermann, R.; Gorkiewicz, G.; Meyer, C.; Rozman, J.; Heldmaier, G.; Maier, R.; Theussl, C.; Eder, S.; et al. Defective lipolysis and altered energy metabolism in mice lacking adipose triglyceride lipase. Science 2006, 312, 734–737. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Rodgers, J.T.; Bare, O.; Lerin, C.; Kim, S.H.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Alt, F.W.; Wu, Z.; Puigserver, P. Metabolic control of muscle mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation through SIRT1/PGC-1α. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 1913–1923. [Google Scholar]

- Gregor, M.F.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Adipocyte stress: The endoplasmic reticulum and metabolic disease. J. Lipid Res. 2007, 48, 1905–1914. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.J.; Kahn, C.R. Endocrine regulation of ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 681–691. [Google Scholar]

- Olefsky, J.M. Fat talks, liver and muscle listen. Cell 2008, 134, 914–916. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, J.T.; Lerin, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Puigserver, P. Metabolic adaptations through the PGC-1α and SIRT1 pathways. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.C.; O’Rourke, E.J.; Ruvkun, G. Fat metabolism links germline stem cells and longevity in C. elegans. Science 2008, 322, 957–960. [Google Scholar]

- Narbonne, P.; Roy, R. Caenorhabditis elegans dauers need LKB1/AMPK to ration lipid reserves and ensure long-term survival. Nature 2009, 457, 210–214. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, L.R.; Gelino, S.; Meléndez, A.; Hansen, M. Autophagy and lipid metabolism coordinately modulate life span in germline-less C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, D.; Gems, D. The mystery of C. elegans aging: An emerging role for fat. Bioessays 2012, 34, 466–471. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, N.S.; Taubert, S. Function and regulation of lipid biology in Caenorhabditis elegans aging. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, L.R.; Meléndez, A.; Hansen, M. Autophagy links lipid metabolism to longevity in C. elegans. Autophagy 2012, 8, 144–146. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, A.; Titorenko, V.I. Essential roles of peroxisomally produced and metabolized biomolecules in regulating yeast longevity. Subcell. Biochem. 2013, 69, 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Liu, J.; Dickson, R.C. Down-regulating sphingolipid synthesis increases yeast lifespan. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002493. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Liu, J.; Withers, B.R.; Samide, A.J.; Leggas, M.; Dickson, R.C. Reducing signs of aging and increasing lifespan by drug synergy. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 652–660. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Withers, B.R.; Blalock, E.; Liu, K.; Dickson, R.C. Reducing sphingolipid synthesis orchestrates global changes to extend yeast lifespan. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 833–841. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Withers, B.R.; Dickson, R.C. Sphingolipids and lifespan regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1841, 657–664. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, E.J.; Kuballa, P.; Xavier, R.; Ruvkun, G. ω-6 Polyunsaturated fatty acids extend life span through the activation of autophagy. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 429–440. [Google Scholar]

- Jové, M.; Naudí, A.; Aledo, J.C.; Cabré, R.; Ayala, V.; Portero-Otin, M.; Barja, G.; Pamplona, R. Plasma long-chain free fatty acids predict mammalian longevity. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, S.; Meyer, T. STIM proteins and the endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane junctions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 973–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.R.; Voeltz, G.K. The ER in 3D: A multifunctional dynamic membrane network. Trends Cell Biol. 2011, 21, 709–717. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, S.A.; Kohlwein, S.D.; Carman, G.M. Metabolism and regulation of glycerolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2012, 190, 317–349. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, A.A.; Voeltz, G.K. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contacts: Function of the junction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 607–625. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, A.; Richard, V.R.; Leonov, A.; Burstein, M.T.; Bourque, S.D.; Koupaki, O.; Juneau, M.; Feldman, R.; Iouk, T.; Titorenko, V.I. Mitochondrial membrane lipidome defines yeast longevity. Aging 2013, 5, 551–574. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, S.E.; Daum, G. Lipids of mitochondria. Prog. Lipid Res. 2013, 52, 590–614. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlwein, S.D.; Veenhuis, M.; van der Klei, I.J. Lipid droplets and peroxisomes: Key players in cellular lipid homeostasis or a matter of fat—store ’em up or burn ’em down. Genetics 2013, 193, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, V.R.; Leonov, A.; Beach, A.; Burstein, M.T.; Koupaki, O.; Gomez-Perez, A.; Levy, S.; Pluska, L.; Mattie, S.; Rafesh, R.; et al. Macromitophagy is a longevity assurance process that in chronologically aging yeast limited in calorie supply sustains functional mitochondria and maintains cellular lipid homeostasis. Aging 2013, 5, 234–269. [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli, S.; Chao, J.T.; Young, B.P.; Cox, R.C.; Prinz, W.A.; de Kroon, A.I.; Loewen, C.J. Plasma membrane-endoplasmic reticulum contact sites regulate phosphatidylcholine synthesis. EMBO Rep. 2013, 14, 434–440. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuta, T.; Scharwey, M.; Langer, T. Mitochondrial lipid trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2014, 24, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.; Pellicciari, R.; Pruzanski, M.; Auwerx, J.; Schoonjans, K. Targeting bile-acid signalling for metabolic diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 678–693. [Google Scholar]

- De Aguiar Vallim, T.Q.; Tarling, E.J.; Edwards, P.A. Pleiotropic roles of bile acids in metabolism. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 657–669. [Google Scholar]

- Hylemon, P.B.; Zhou, H.; Pandak, W.M.; Ren, S.; Gil, G.; Dent, P. Bile acids as regulatory molecules. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, P.; Cariou, B.; Lien, F.; Kuipers, F.; Staels, B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 147–191. [Google Scholar]

- Vallim, T.Q.; Edwards, P.A. Bile acids have the gall to function as hormones. Cell Metab. 2009, 10, 162–164. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, J.Y. Bile acids: Regulation of synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, 1955–1966. [Google Scholar]

- Monte, M.J.; Marin, J.J.; Antelo, A.; Vazquez-Tato, J. Bile acids: Chemistry, physiology, and pathophysiologY. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 804–816. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, A.; Maiti, P. TGR5: An emerging bile acid G-protein-coupled receptor target for the potential treatment of metabolic disorders. Drug Discov. Today 2009, 14, 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Pols, T.W.; Noriega, L.G.; Nomura, M.; Auwerx, J.; Schoonjans, K. The bile acid membrane receptor TGR5 as an emerging target in metabolism and inflammation. J. Hepatol. 2011, 54, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, J.Y. Bile acid metabolism and signaling. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 1191–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Chiang, J.Y. Nuclear receptors in bile acid metabolism. Drug Metab. Rev. 2013, 45, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Amador-Noguez, D.; Yagi, K.; Venable, S.; Darlington, G. Gene expression profile of long-lived Ames dwarf mice and Little mice. Aging Cell 2004, 3, 423–441. [Google Scholar]

- Amador-Noguez, D.; Dean, A.; Huang, W.; Setchell, K.; Moore, D.; Darlington, G. Alterations in xenobiotic metabolism in the long-lived Little mice. Aging Cell 2007, 6, 453–470. [Google Scholar]

- Gems, D. Long-lived dwarf mice: Are bile acids a longevity signal? Aging Cell 2007, 6, 421–423. [Google Scholar]

- Gems, D.; Partridge, L. Stress-response hormesis and aging: “That which does not kill us makes us stronger”. Cell Metab. 2008, 7, 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Motola, D.L.; Cummins, C.L.; Rottiers, V.; Sharma, K.K.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Suino-Powell, K.; Xu, H.E.; Auchus, R.J.; Antebi, A.; et al. Identification of ligands for DAF-12 that govern dauer formation and reproduction in C. elegans. Cell 2006, 124, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Wollam, J.; Magomedova, L.; Magner, D.B.; Shen, Y.; Rottiers, V.; Motola, D.L.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Cummins, C.L.; Antebi, A. The Rieske oxygenase DAF-36 functions as a cholesterol 7-desaturase in steroidogenic pathways governing longevity. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 879–884. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.S.; Schroeder, F.C. Steroids as central regulators of organismal development and lifespan. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001307. [Google Scholar]

- Wollam, J.; Magner, D.B.; Magomedova, L.; Rass, E.; Shen, Y.; Rottiers, V.; Habermann, B.; Cummins, C.L.; Antebi, A. A novel 3-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase that regulates reproductive development and longevity. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001305. [Google Scholar]

- Groen, A.K.; Kuipers, F. Bile acid look-alike controls life span in C. elegans. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 151–152. [Google Scholar]

- Magner, D.B.; Wollam, J.; Shen, Y.; Hoppe, C.; Li, D.; Latza, C.; Rottiers, V.; Hutter, H.; Antebi, A. The NHR-8 nuclear receptor regulates cholesterol and bile acid homeostasis in C. elegans. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 212–224. [Google Scholar]

- Mahanti, P.; Bose, N.; Bethke, A.; Judkins, J.C.; Wollam, J.; Dumas, K.J.; Zimmerman, A.M.; Campbell, S.L.; Hu, P.J.; Antebi, A.; et al. Comparative metabolomics reveals endogenous ligands of DAF-12, a nuclear hormone receptor, regulating C. elegans development and lifespan. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Burstein, M.T.; Kyryakov, P.; Beach, A.; Richard, V.R.; Koupaki, O.; Gomez-Perez, A.; Leonov, A.; Levy, S.; Noohi, F.; Titorenko, V.I. Lithocholic acid extends longevity of chronologically aging yeast only if added at certain critical periods of their lifespan. Cell Cycle 2012, 11, 3443–3462. [Google Scholar]

- Burstein, M.T.; Titorenko, V.I. A mitochondrially targeted compound delays aging in yeast through a mechanism linking mitochondrial membrane lipid metabolism to mitochondrial redox biology. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 305–307. [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani, S.; Richard, V.R.; Beach, A.; Leonov, A.; Feldman, R.; Mattie, S.; Khelghatybana, L.; Piano, A.; Greenwood, M.; Vali, H.; et al. Macromitophagy, neutral lipids synthesis, and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation protect yeast from “liponecrosis”, a previously unknown form of programmed cell death. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, R.A. The Biology of Cancer, 2nd ed.; Garland Science, Taylor & Francis Group, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2007; p. 876. [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar]

- Campisi, J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: Good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell 2005, 120, 513–522. [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. Aging and immortality: Quasi-programmed senescence and its pharmacologic inhibition. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 2087–2102. [Google Scholar]

- Campisi, J.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Cellular senescence: When bad things happen to good cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 729–740. [Google Scholar]

- Collado, M.; Blasco, M.A.; Serrano, M. Cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Cell 2007, 130, 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel, T.; Serrano, M.; Blasco, M.A. The common biology of cancer and ageing. Nature 2007, 448, 767–774. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, M.; Blasco, M.A. Cancer and ageing: Convergent and divergent mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 715–722. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, P.D. Healing and hurting: Molecular mechanisms, functions, and pathologies of cellular senescence. Mol. Cell 2009, 36, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny, M.V.; Hall, M.N. Growth and aging: A common molecular mechanism. Aging 2009, 1, 357–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani, N.; Mann, D.J.; Hara, E. Cellular senescence: Its role in tumor suppression and aging. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100, 792–797. [Google Scholar]

- Rodier, F.; Campisi, J. Four faces of cellular senescence. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 192, 547–556. [Google Scholar]

- Campisi, J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013, 75, 685–705. [Google Scholar]

- Piano, A.; Titorenko, V.I. The intricate interplay between mechanisms underlying aging and cancer. Aging Dis. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, A.A.; Beach, A.; Davies, G.F.; Harkness, T.A.A.; LeBlanc, A.; Titorenko, V.I. Lithocholic bile acid selectively kills neuroblastoma cells, while sparing normal neuronal cells. Oncotarget 2011, 2, 761–782. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, A.A.; Beach, A.; Titorenko, V.I.; Sanderson, J.T. Bile acids induce apoptosis selectively in androgen-dependent and -independent prostate cancer cells. Peer J. 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Miyamoto, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Tamai, Y.; Okada, H.; Sugiyama, E.; Nakamura, T.; Itadani, H.; Tanaka, K. Identification of membrane-type receptor for bile acids (M-BAR). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 298, 714–719. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata, Y.; Fujii, R.; Hosoya, M.; Harada, M.; Yoshida, H.; Miwa, M.; Fukusumi, S.; Habata, Y.; Itoh, T.; Shintani, Y.; et al. G protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 9435–9440. [Google Scholar]

- Wachs, F.P.; Krieg, R.C.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Messmann, H.; Kullmann, F.; Knüchel-Clarke, R.; Schölmerich, J.; Rogler, G.; Schlottmann, K. Bile salt-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cell lines involves the mitochondrial transmembrane potential but not the CD95 (Fas/Apo-1) receptor. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2005, 20, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, R.A.; Dagda, R.K.; Dickey, A.S.; Cribbs, J.T.; Green, S.H.; Usachev, Y.M.; Strack, S. Mechanism of neuroprotective mitochondrial remodeling by PKA/AKAP1. PLoS Biol. 2011, 9, e1000612. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.C.; Cullen, S.P.; Martin, S.J. Apoptosis: Controlled demolition at the cellular level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Tait, S.W.; Green, D.R. Mitochondria and cell death: Outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 621–632. [Google Scholar]

- Kersse, K.; Vanden Berghe, T.; Lamkanfi, M.; Vandenabeele, P. A phylogenetic and functional overview of inflammatory caspases and caspase-1-related CARD-only proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 1508–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello, C.A. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 27, 519–550. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, M.; Rüegg, A.; Werner, S.; Beer, H.D. Active caspase-1 is a regulator of unconventional protein secretion. Cell 2009, 132, 818–831. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, C.H.; Yuan, J. The Jekyll and Hyde functions of caspases. Dev. Cell 2009, 16, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Jiang, S.; Tapping, R.I. Toll-like receptor signaling in cell proliferation and survival. Cytokine 2010, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Donath, M.Y.; Shoelson, S.E. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov, S.I.; Karin, M. Inflammatory cytokines in cancer: Tumour necrosis factor and interleukin 6 take the stage. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, i104–i108. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Arlia-Ciommo, A.; Piano, A.; Svistkova, V.; Mohtashami, S.; Titorenko, V.I. Mechanisms Underlying the Anti-Aging and Anti-Tumor Effects of Lithocholic Bile Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 16522-16543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150916522

Arlia-Ciommo A, Piano A, Svistkova V, Mohtashami S, Titorenko VI. Mechanisms Underlying the Anti-Aging and Anti-Tumor Effects of Lithocholic Bile Acid. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014; 15(9):16522-16543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150916522

Chicago/Turabian StyleArlia-Ciommo, Anthony, Amanda Piano, Veronika Svistkova, Sadaf Mohtashami, and Vladimir I. Titorenko. 2014. "Mechanisms Underlying the Anti-Aging and Anti-Tumor Effects of Lithocholic Bile Acid" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 15, no. 9: 16522-16543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150916522

APA StyleArlia-Ciommo, A., Piano, A., Svistkova, V., Mohtashami, S., & Titorenko, V. I. (2014). Mechanisms Underlying the Anti-Aging and Anti-Tumor Effects of Lithocholic Bile Acid. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 15(9), 16522-16543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150916522