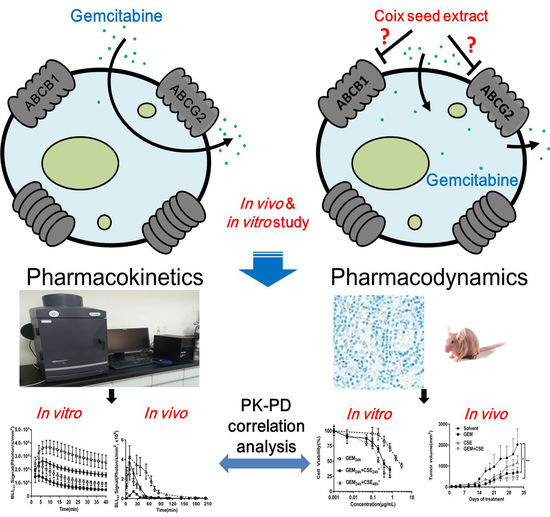

Coix Seed Extract Enhances the Anti-Pancreatic Cancer Efficacy of Gemcitabine through Regulating ABCB1- and ABCG2-Mediated Drug Efflux: A Bioluminescent Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Determination of the Linear Correlation Range of Bioluminescence Intensity In Vitro and In Vivo

2.2. Coix Seed Extract Sensitized Pancreatic Cancer Cells BxPC3luc and PANC-1 to Gemcitabine Exposure

2.3. The Coix Seed Extract Significantly Reversed Gemcitabine-Induced Decreases in Intracellular Bioluminescent Signal and Gemcitabine Accumulationin BxPC3luc Cells

2.4. Coix Seed Extract and Gemcitabine in Combination Exhibited Potential Antitumor Growth Efficacy

2.5. The Characterization of the Intracellular Pharmacokinetic Profiles of Bioluminescence In Vivo after Exposure to Coix seed Extract and Gemcitabine

2.6. The Intracellular Bioluminescent Pharmacokinetic Parameter AUC Showed Potential Associations with Anti-Pancreatic Cancer Efficacy In Vitro and In Vivo

2.7. Coix Seed Extract Reverses Gemcitabine-Induced Upregulation ABCB1 and ABCG2 Protein Level In Vitro and In Vivo

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. Cell Viability Assay

4.4. Animal Study

4.5. Luciferin Assay and Pharmacokinetic Analysis

4.5.1. In Vitro Bioluminescent Assay

4.5.2. In Vivo Bioluminescent Assay

4.5.3. Bioluminescent Pharmacokinetic Parameters

4.6. Immunohistochemical Analysis and Assessment

4.7. Western Blot Analysis

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABC transportersAUC | ATP-binding cassette transportersarea under the curve |

| BLI | bioluminescence imaging |

| BLIrel | relative bioluminescence imaging |

| CSE | coix seed extract |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| GEM | gemcitabine |

| K | elimination rate constant |

| MDR | multidrug resistance |

| MRT | mean resident time |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| PD | pharmacodynamics |

| PK | pharmacokinetics |

| SDS-PAGE electrophoresis | sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| SNR | signal-to-noise ratio |

References

- Tamburrino, A.; Piro, G.; Carbone, C.; Tortora, G.; Melisi, D. Mechanisms of resistance to chemotherapeutic and anti-angiogenic drugs as novel targets for pancreatic cancer therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2013, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vaccaro, V.; Sperduti, I.; Vari, S.; Bria, E.; Melisi, D.; Garufi, C.; Nuzzo, C.; Scarpa, A.; Tortora, G.; Cognetti, F.; et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: Is there a light at the end of the tunnel? World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 4788–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa Cavalcante, L.; Monteiro, G. Gemcitabine: Metabolism and molecular mechanisms of action, sensitivity and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 741, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, H.L.; Yang, Y.J.; Wang, L.; Lee, S.C. Overcome Cancer Cell Drug Resistance Using Natural Products. Evid.-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 767136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Yu, X.J.; Yang, J.X.; LeBrun, D.G.; Chen, C.Y.; Yao, Q.Z.; Li, M. Overcoming drug resistance in pancreatic cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2011, 15, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, X.; Wang, J.; Wei, W.; Shi, M.; Xin, B.; Zhang, T.; Shen, X. Hypoxia regulates ABCG2 activity through the activivation of ERK1/2/HIF-1alpha and contributes to chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2016, 17, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, A.M.; Pinedo, H.M.; Talianidis, I.; Veerman, G.; Loves, W.J.; van der Wilt, C.L.; Peters, G.J. Increased sensitivity to gemcitabine of P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated protein-overexpressing human cancer cell lines. Br. J. Cancer 2003, 88, 1963–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohan, H.G.; Boroujerdi, M. Time and concentration dependency of P-gp, MRP1 and MRP5 induction in response to gemcitabine uptake in Capan-2 pancreatic cancer cells. Xenobiotica 2015, 45, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Li, A.; Inagaki, Y.; Gao, J.; Li, J.; Kokudo, N.; Li, X.K.; Tang, W. Chinese herbal medicines as adjuvant treatment during chemo- or radio-therapy for cancer. Biosci. Trends 2010, 4, 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg, L.S.; Arena, F.P.; Bienvenu, B.J.; Kaplan, E.H.; Camacho, L.H.; Campos, L.T.; Waymack, J.P.; Tagliaferri, M.A.; Chen, M.M.; Li, D. A Randomized, Open-Label, Safety and Exploratory Efficacy Study of Kanglaite Injection (KLTi) plus Gemcitabine versus Gemcitabine in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 1872–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, C.Y.; Liu, T.; Wu, B.; Zhou, F.; Xiong, J.X.; Wu, H.S.; Tao, J.; Zhao, G.; Yang, M.; et al. Persistence of side population cells with high drug efflux capacity in pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yao, L.; Gu, J.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Jin, C.; Fu, D.; Li, J. Dynamic quantitative detection of ABC transporter family promoter methylation by MS-HRM for predicting MDR in pancreatic cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 5602–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarfe, L.; Taylor, A.; Sharkey, J.; Harwood, R.; Barrow, M.; Comenge, J.; Beeken, L.; Astley, C.; Santeramo, I.; Hutchinson, C.; et al. Non-invasive imaging reveals conditions that impact distribution and persistence of cells after in vivo administration. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.M.; Callstrom, M.R.; Knudsen, B.E.; Anderson, J.L.; Sutor, S.L.; Butters, K.A.; Kuo, C.; Grande, J.P.; Roberts, L.R.; Woodrum, D.A. Molecular bioluminescence imaging as a noninvasive tool for monitoring tumor growth and therapeutic response to MRI-guided laser ablation in a rat model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Investig. Radiol. 2013, 48, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Close, D.M.; Xu, T.; Sayler, G.S.; Ripp, S. In vivo bioluminescent imaging (BLI): Noninvasive visualization and interrogation of biological processes in living animals. Sensors 2011, 11, 180–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.; Bibee, K.; Wickline, S.; Sept, D. Pharmacokinetic modeling of tumor bioluminescence implicates efflux, and not influx, as the bigger hurdle in cancer drug therapy. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gu, M.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Xiong, Y.; Wei, Y.; Li, F. Gemcitabine upregulates ABCG2/BCRP and modulates the intracellular pharmacokinetic profiles of bioluminescence in pancreatic cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs 2016, 27, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.Y.; Zhu, L.X.; Yu, J.D.; Chen, Z.; Gu, M.C.; Mu, C.F.; Liu, Q.; Xiong, Y. Effect of beta-elemene on the kinetics of intracellular transport of d-luciferin potassium salt (ABC substrate) in doxorubicin-resistant breast cancer cells and the associated molecular mechanism. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 120, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.S.; Wei, B.R.; Madigan, J.P.; Simpson, R.M.; Hall, M.D.; Gottesman, M.M. Bioluminescent imaging of ABCG2 efflux activity at the blood-placenta barrier. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yasuda, K.; Cline, C.; Lin, Y.S.; Scheib, R.; Ganguly, S.; Thirumaran, R.K.; Chaudhry, A.; Kim, R.B.; Schuetz, E.G. In Vivo Imaging of Human MDR1 Transcription in the Brain and Spine of MDR1-Luciferase Reporter Mice. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.L.; Chou, C.C.; Lai, P.T.; Fang, C.S.; Shirley, L.A.; Yan, R.; Mo, X.; Bloomston, M.; Kulp, S.K.; Bekaii-Saab, T.; et al. Targeting the Warburg effect with a novel glucose transporter inhibitor to overcome gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 2203–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Pullambhatla, M.; Laterra, J.; Pomper, M.G. Influence of bioluminescence imaging dynamics by D-luciferin uptake and efflux mechanisms. Mol. Imaging 2012, 11, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, D.; Li, L.; Niu, N.; Kalari, K.R.; Gilbert, J.A.; Ames, M.M.; Wang, L. Gemcitabine Cytotoxicity: Interaction of Efflux and Deamination. J. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2011, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gottesman, M.M.; Pastan, I.H. The Role of Multidrug Resistance Efflux Pumps in Cancer: Revisiting a JNCI Publication Exploring Expression of the MDR1 (P-glycoprotein) Gene. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.J.; Liu, S. Antitumor effect of Kanglaite(R) injection in human pancreatic cancer xenografts. BMC Complement. Altern Med. 2014, 14, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, C.S.; Dong, Q. Chinese herb related molecules of cancer-cell-apoptosis: A minireview of progress between Kanglaite injection and related genes. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 27, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B. Network meta-analysis of Chinese herbal injections combined with the chemotherapy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017, 96, e7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Hou, S. Kanglaite sensitizes colorectal cancer cells to Taxol via NF-kappaBeta inhibition and connexin 43 upregulation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Z.Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.J.; Yuan, Y.F. Antitumor activity and immunomodulatory effects of the intraperitoneal administration of Kanglaite in vivo in Lewis lung carcinoma. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Yang, B.; Xiong, Y.; Gu, M. Coix seed emulsion synergistically enhances the antitumor activity of gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer through abrogation of NF-kappaB signaling. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hou, A.; Yu, C.; Dai, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, K.; Shao, H.; Ma, J.; Xu, W. Kanglaite reverses multidrug resistance of HCC by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest via PI3K/AKT pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.W.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.Z.; Bo, P. Kanglaite inhibits the expression of drug resistance genes through suppressing PVT1 in cisplatin-resistant gastric cancer cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 1789–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adamska, A.; Falasca, M. ATP-binding cassette transporters in progression and clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer: What is the way forward? World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 3222–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Park, S.B.; Kim, S.A.; Kwon, S.K.; Cha, H.; Lee, D.Y.; Ro, S.; Cho, J.M.; Song, S.Y. A novel HDAC inhibitor, CG200745, inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth and overcomes gemcitabine resistance. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakano, Y.; Tanno, S.; Koizumi, K.; Nishikawa, T.; Nakamura, K.; Minoguchi, M.; Izawa, T.; Mizukami, Y.; Okumura, T.; Kohgo, Y. Gemcitabine chemoresistance and molecular markers associated with gemcitabine transport and metabolism in human pancreatic cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, S.; Shiraha, H.; Nagahara, T.; Kataoka, J.; Iwamuro, M.; Matsubara, M.; Nishina, S.; Kato, H.; Takaki, A.; Nouso, K.; et al. Loss of runt-related transcription factor 3 induces gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2013, 7, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Zhang, B.S.; Prescher, J.A. Advances in bioluminescence imaging: New probes from old recipes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2018, 45, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, A.; Sarkisyan, K.S. A brief review of bioluminescent systems (2019). Curr Genet. 2019, 65, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tung, J.K.; Berglund, K.; Gutekunst, C.A.; Hochgeschwender, U.; Gross, R.E. Bioluminescence imaging in live cells and animals. Neurophotonics 2016, 3, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bressler, J.P.; Neal, J.; Lal, B.; Bhang, H.E.; Laterra, J.; Pomper, M.G. ABCG2/BCRP expression modulates D-Luciferin based bioluminescence imaging. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 9389–9397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettig, G.R.; McAnuff, M.; Liu, D.; Kim, J.S.; Rice, K.G. Quantitative bioluminescence imaging of transgene expression in vivo. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 355, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mairinger, S.; Zoufal, V.; Wanek, T.; Traxl, A.; Filip, T.; Sauberer, M.; Stanek, J.; Kuntner, C.; Pahnke, J.; Muller, M.; et al. Influence of breast cancer resistance protein and P-glycoprotein on tissue distribution and excretion of Ko143 assessed with PET imaging in mice. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 115, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hsu, M.C.; Pan, M.R.; Chu, P.Y.; Tsai, Y.L.; Tsai, C.H.; Shan, Y.S.; Chen, L.T.; Hung, W.C. Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 3 Enhances Chemoresistance in Pancreatic Cancer by Methylating hnRNPA1 to Increase ABCG2 Expression. Cancers 2018, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.P.; Wen, J.; Bang, S.; Park, S.; Song, S.Y. CD44-positive cells are responsible for gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 2323–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Schwarz, B.; Mysliwietz, J.; Hartig, R.; Camaj, P.; Bao, Q.; Jauch, K.W.; Guba, M.; Ellwart, J.W.; et al. Verapamil inhibits tumor progression of chemotherapy-resistant pancreatic cancer side population cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmarajan, K.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Normand, S.T.; Ross, J.S.; Horwitz, L.I.; Desai, N.R.; Suter, L.G.; Drye, E.E.; Bernheim, S.M.; et al. Association of Changing Hospital Readmission Rates With Mortality Rates After Hospital Discharge. JAMA 2017, 318, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.F.; Tao, M.T.; He, Y.Z.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.H.; Liao, X.P. In Vivo Bioluminescent Monitoring of Therapeutic Efficacy and Pharmacodynamic Target Assessment of Antofloxacin against Escherichia coli in a Neutropenic Murine Thigh Infection Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01281-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.Q.; Wen, Y.; Gupta, P.; Lei, Z.N.; Cai, C.Y.; Liang, G.; Yang, D.H.; Chen, Z.S.; Xie, Y.A. Y6, an Epigallocatechin Gallate Derivative, Reverses ABCG2-Mediated Mitoxantrone Resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, Y.; Schuetz, J.D. ABC transporters and their role in nucleoside and nucleotide drug resistance. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hagmann, W.; Jesnowski, R.; Faissner, R.; Guo, C.; Lohr, J.M. ATP-binding cassette C transporters in human pancreatic carcinoma cell lines. Upregulation in 5-fluorouracil-resistant cells. Pancreatology 2009, 9, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauswald, S.; Duque-Afonso, J.; Wagner, M.M.; Schertl, F.M.; Lubbert, M.; Peschel, C.; Keller, U.; Licht, T. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce a very broad, pleiotropic anticancer drug resistance phenotype in acute myeloid leukemia cells by modulation of multiple ABC transporter genes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3705–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.H.; Li, D.; Wilsbach, K.; Orita, H.; Coulter, J.; Tully, E.; Kwon, T.K.; Xu, S.; Gabrielson, E. Coix seed extract, a commonly used treatment for cancer in China, inhibits NFkappaB and protein kinase C signaling. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007, 6, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.H.; Kim, A.R.; Nam, J.K.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Seo, H.R.; Lee, H.J.; Cho, J.; Lee, Y.J. Tumour-vasculature development via endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition after radiotherapy controls CD44v6+ cancer cell and macrophage polarization. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | AUCluc(* 105, BLIrel × min) | MRTluc (min) | Kluc(* 10−3, min−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | |

| DMSO | 3136.00 ± 620.56 | 1201.00 ± 218.90 | 802.00 ± 54.63 | 17.20 ± 0.60 | 18.96 ± 0.40 | 19.20 ± 0.60 | 7.80 ± 1.00 | 8.10 ± 0.39 | 8.73 ± 0.40 |

| GEM | 1853.00 ± 273.86 ** | 327.00 ± 63.86 ** | 319.00 ± 63.91 ** | 17.18 ± 0.60 | 17.30 ± 0.60 ** | 16.31 ± 0.20 ** | 9.40 ± 1.90 | 14.48 ± 2.09 ** | 20.03 ± 3.18 ** |

| CSE | 5076.00 ± 164.66 | 1974.00 ± 9.20 | 1220.00 ± 173.40 | 20.31 ± 0.09 | 20.92 ± 0.20 | 19.54 ± 0.50 | 7.09 ± 0.49 | 8.10 ± 0.50 | 11.03 ± 1.27 |

| GEM + CSE | 2334.50 ± 182.18 ## | 524.17 ± 127.43 ## | 533.00 ± 82.27 ## | 18.64 ± 0.62 ## | 17.64 ± 0.50 | 17.06 ± 0.50 ## | 9.44 ± 1.50 ## | 12.56 ± 0.59 ## | 16.06 ± 0.62 ## |

| Group | AUCluc(* 107, BLIrel × min) | MRTluc (min) | Kluc(* 10−3, min−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7d | 14d | 25d | 7d | 14d | 25d | 7d | 14d | 25d | |

| Solvent | 1074.67 ± 164.83 | 1095.83 ± 61.65 | 1013.33 ± 67.00 | 22.69 ± 1.13 | 23.20 ± 1.42 | 24.40 ± 2.10 | 16.17 ± 5.38 | 22.65 ± 2.42 | 24.28 ± 3.41 |

| GEM | 250.67 ± 138.70 ** | 229.00 ± 23.19 ** | 182.00 ± 94.16 ** | 18.70 ± 1.35 ** | 16.89 ± 2.89 ** | 16.13 ± 0.66 ** | 26.03 ± 1.63 ** | 29.07 ± 0.76 ** | 34.97 ± 3.20 ** |

| CSE | 2321.83 ± 65.00 | 2366.67 ± 177.91 | 2554.00 ± 134.65 | 34.05 ± 0.41 | 37.23 ± 3.02 | 44.37 ± 1.86 | 12.03 ± 1.35 | 14.00 ± 3.89 | 15.97 ± 1.85 |

| GEM + CSE | 718.00 ± 75.83 ## | 796.17 ± 269.14 ## | 658.83 ± 132.24 ## | 20.53 ± 0.34 ## | 23.36 ± 0.68 ## | 26.21 ± 2.81 ## | 15.03 ± 1.49 ## | 23.03 ± 1.01 ## | 23.03 ± 1.83 ## |

| Group | Pearson Coefficient | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| GEM + CSE | ||

| AUCluc in vitro v.s | 0.723 | < 0.001 |

| AUCluc in vivo | ||

| MRTluc in vitro v.s | −0.752 | < 0.001 |

| MRTluc in vivo | ||

| Kluc in vitro v.s | 0.735 | < 0.001 |

| Kluc in vivo | ||

| GEM | ||

| AUCluc in vitro v.s | 0.762 | < 0.001 |

| AUCluc in vivo | ||

| MRTluc in vitro v.s | −0.102 | 0.344 |

| MRTluc in vivo | ||

| Kluc in vitro v.s | 0.907 | < 0.001 |

| Kluc in vivo | ||

| CSE | ||

| AUCluc in vitro v.s | 0.994 | < 0.001 |

| AUCluc in vivo | ||

| MRTluc in vitro v.s | −0.524 | 0.013 |

| MRTluc in vivo | ||

| Kluc in vitro v.s Kluc in vivo | 0.839 | < 0.001 |

| Group | Pearson Coefficient | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Association | |||

| IC50 value of GEM + CSE v.s. | |||

| AUCluc | −0.460 | 0.027 | |

| MRTluc | −0.103 | 0.342 | |

| Kluc | 0.436 | 0.035 | |

| IC50 value of GEM v.s. | |||

| AUCluc | −0.580 | 0.006 | |

| MRTluc | −0.038 | 0.441 | |

| Kluc | 0.422 | 0.041 | |

| IC50 value of CSE v.s. | |||

| AUCluc | −0.609 | 0.004 | |

| MRTluc | −0.639 | 0.002 | |

| Kluc | 0.403 | 0.049 | |

| In vivo association | |||

| TGI value of GEM + CSE v.s. | |||

| AUCluc | 0.391 | 0.054 | |

| MRTluc | 0.056 | 0.413 | |

| Kluc | −0.360 | 0.071 | |

| TGI value of GEM v.s. | |||

| AUCluc | 0.452 | 0.030 | |

| MRTluc | 0.092 | 0.358 | |

| Kluc | −0.173 | 0.246 | |

| TGI value of CSE v.s. | |||

| AUCluc | 0.334 | 0.087 | |

| MRTluc | 0.241 | 0.167 | |

| Kluc | −0.013 | 0.480 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qian, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Feng, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Gu, M. Coix Seed Extract Enhances the Anti-Pancreatic Cancer Efficacy of Gemcitabine through Regulating ABCB1- and ABCG2-Mediated Drug Efflux: A Bioluminescent Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20215250

Qian Y, Xiong Y, Feng D, Wu Y, Zhang X, Chen L, Gu M. Coix Seed Extract Enhances the Anti-Pancreatic Cancer Efficacy of Gemcitabine through Regulating ABCB1- and ABCG2-Mediated Drug Efflux: A Bioluminescent Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(21):5250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20215250

Chicago/Turabian StyleQian, Yifan, Yang Xiong, Di Feng, Yali Wu, Xu Zhang, Liping Chen, and Mancang Gu. 2019. "Coix Seed Extract Enhances the Anti-Pancreatic Cancer Efficacy of Gemcitabine through Regulating ABCB1- and ABCG2-Mediated Drug Efflux: A Bioluminescent Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Study" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 21: 5250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20215250

APA StyleQian, Y., Xiong, Y., Feng, D., Wu, Y., Zhang, X., Chen, L., & Gu, M. (2019). Coix Seed Extract Enhances the Anti-Pancreatic Cancer Efficacy of Gemcitabine through Regulating ABCB1- and ABCG2-Mediated Drug Efflux: A Bioluminescent Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(21), 5250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20215250