Antibacterial Activity of Selected Essential Oil Compounds Alone and in Combination with β-Lactam Antibiotics Against MRSA Strains

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) Results

2.2. Presence of MecA Gene and PFGE Results

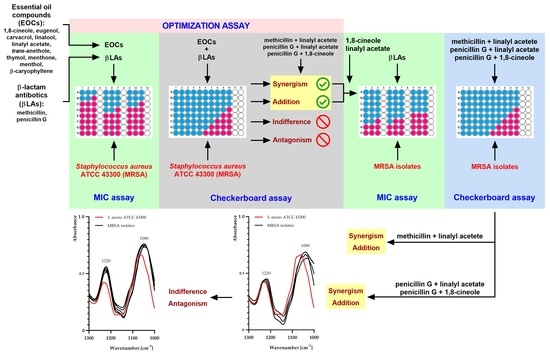

2.3. Optimization Assay Results

2.4. Antibacterial Effects of Selected Combinations of EOCs and β-Lactam Antibiotics against MRSA Isolates

2.5. FTIR Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Condition

4.2. Chemicals

4.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (AST) Assay

4.4. MecA Gene Detection

4.4.1. DNA Isolation

4.4.2. PCR Amplification

4.5. Macro-Restriction Analysis of Genomic DNA of MRSA Isolates

4.6. Combination of EOCs with β-Lactam Antibiotics—Optimization Assay

4.7. Determination of MIC and FICI of Chemicals against Isolates

4.8. S. aureus Strains—FTIR Spectroscopic Measurements

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EOs | essential oils |

| EOCs | essential oil compounds |

| FICI | fractional inhibitory concentration index |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| MIC | minimal inhibitory concentration |

| MLSB | phenotype expressing resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins B |

| MRSA | methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| PFGE | pulsed-field gel electrophoresis |

References

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Xu, Y.; Xie, X.; Chen, M. In vitro activity of ceftobiprole, linezolid, tigecycline, and 23 other antimicrobial agents against Staphylococcus aureus isolates in China. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008, 62, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. Understanding the evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 2009, 31, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiramatsu, K.; Cui, L.; Kuroda, M.; Ito, T. The emergence and evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 2001, 9, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Moodley, A.; Strasheim, W.; Mogokotleng, R.; Ismail, H.; Perovic, O. Unconventional SCCmec types and low prevalence of the Panton-Valentine leukocidin exotoxin in South African blood culture Staphylococcus aureus surveillance isolates, 2013–2016. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 0225726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Bayer, A.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Daum, R.S.; Fridkin, S.K.; Gorwitz, R.J.; Kaplan, S.L.; Karchmer, A.W.; Levine, D.P.; Murray, B.E.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, 18–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, A.S.; de Lencastre, H.; Garau, J.; Kluytmans, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Peschel, A.; Harbarth, S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, K.; Sunnucks, K.; Gil, H.; Shabir, S.; Trampari, E.; Hawkey, P.; Webber, M. Increased usage of antiseptics is associated with reduced susceptibility in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. mBio 2018, 9, 00894-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muntean, D.; Licker, M.; Alexa, E.; Popescu, I.; Jianu, C.; Buda, V.; Dehelean, C.A.; Ghiulai, R.; Horhat, F.; Horhat, D.; et al. Evaluation of essential oil obtained from Mentha × piperita L. against multidrug-resistant strains. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 2905–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kali, A. Antibiotics and bioactive natural products in treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A brief review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2015, 9, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Badawy, M.E.I.; Marei, G.I.K.; Rabea, E.I.; Taktak, N.E.M. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of hydrocarbon and oxygenated monoterpenes against some foodborne pathogens through in vitro and in silico studies. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 158, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, P.; Pruss, A.; Wojciuk, B.; Dołęgowska, B.; Wajs-Bonikowska, A.; Sienkiewicz, M.; Mężyńska, M.; Łopusiewicz, Ł. The influence of essential oil compounds on antibacterial activity of mupirocin-susceptible and induced low-level mupirocin-resistant MRSA strains. Molecules 2019, 24, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kifer, D.; Mužinic, V.; Klarić, M.Š. Antimicrobial potency of single and combined mupirocin and monoterpenes, thymol, menthol and 1,8-cineole against Staphylococcus aureus planktonic and biofilm growth. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2016, 69, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, P.; Łopusiewicz, Ł.; Kostek, M.; Drozłowska, E.; Pruss, A.; Wojciuk, B.; Sienkiewicz, M.; Zielińska-Bliźniewska, H.; Dołęgowska, B. The antibacterial activity of lavender essential oil alone and in combination with octenidine dihydrochloride against MRSA strains. Molecules 2019, 25, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Forrest, G.N.; Tamura, K. Rifampin combination therapy for nonmycobacterial infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Graber, C.J. Limitations of antibiotic options for invasive infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Is combination therapy the answer? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.S.X.; Yiap, B.C.; Ping, H.C.; Lim, S.H.E. Essential oils, a new horizon in combating bacterial antibiotic resistance. Open Microbiol. J. 2014, 8, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonyanugomol, W.; Kraisriwattana, K.; Rukseree, K.; Boonsam, K.; Narachai, P. In vitro synergistic antibacterial activity of the essential oil from Zingiber cassumunar RoxB against extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahboubi, M.; Bidgoli, F.G. Antistaphylococcal activity of Zataria multiflora essential oil and its synergy with vancomycin. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 548–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, P.; Pruss, A.; Grygorcewicz, B.; Wojciuk, B.; Dołęgowska, B.; Giedrys-Kalemba, S.; Kochan, E.; Sienkiewicz, M. Preliminary study on the antibacterial activity of essential oils alone and in combination with gentamicin against extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzair, B.; Niaz, N.; Bano, A.; Khan, B.A.; Zafar, N.; Iqbal, M.; Tahira, R.; Fasim, F. Essential oils showing in vitro anti MRSA and synergistic activity with penicillin group of antibiotics. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 30, 1997–2002. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, L.; Webb, J.P.; Green, J.; Smith, L.J.; Laird, K. From formulation to in vivo model: A comprehensive study of a synergistic relationship between vancomycin, carvacrol, and cuminaldehyde against Enterococcus faecium. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aelenei, P.; Rimbu, C.M.; Guguianu, E.; Dimitru, G.; Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Brebu, M.; Horhogea, C.E.; Miron, A. Coriander essential oil and linalool - interaction with antibiotics against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehrl, W.; Sonnemann, U.; Dethlefsen, U. Therapy for acute nonpurulent rhinosinusitis with cineole: Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Laryngoscope 2004, 114, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, J.C. Commercial sources, uses, formation, and biologic. In Eucalyptus Leaf Oils: Use, Chemistry, Distillation and Marketing; Boland, D.J., Brophy, J.J., House, A.P.N., Eds.; Inkata Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1991; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Remmal, A.; Akhmouch, A.A. Pharmaceutical Formulation Comprising Cineole and Amoxicillin. U.S. Patent 16,306,262, 22 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hriouech, S.; Akhmouch, A.A.; Mzabi, A.; Chefchaou, H.; Tanghort, M.; Oumokhtar, B.; Chami, N.; Remmal, A. The antistaphylococcal activity of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, gentamicin, and 1,8-cineole alone or in combination and their efficacy through a rabbit model of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 4271017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orchard, A.; van Vuuren, S. Commercial essential oils as potential antimicrobials to treat skin diseases. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 4517971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trombetta, D.; Castelli, F.; Sarpietro, M.G.; Venuti, V.; Cristani, M.; Daniele, C.; Saija, A.; Mazzanti, G.; Bisignano, G. Mechanisms of antibacterial action of three monoterpenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2474–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lopez-Romero, J.; González-Ríos, H.; Borges, A.; Simões, M. Antibacterial effects and mode of action of selected essential oils components against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 795435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Łopusiewicz, Ł.; Mazurkiewicz-Zapałowicz, K.; Tkaczuk, C. Chemical changes in spores of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii after exposure to heavy metals, studied through the use of FTIR spectroscopy. J. Elem. 2019, 25, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, K.; Perez-Guaita, D.; Pissang, J.; Jiang, J.-H.; Peleg, A.Y.; McNaughton, D.; Heraud, P.; Wood, B.R. In vivo atomic force microscopy-infrared spectroscopy of bacteria. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20180115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thumanu, K.; Cha, J.; Fisher, J.F.; Perrins, R.; Mobashery, S.; Wharton, C. Discrete steps in sensing of β-lactam antibiotics by the BlaR1 protein of the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10630–10635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters; Version 10.0; EUCAST: Växjö, Sweden, 2020; Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Zhang, K.; Sparling, J.; Chow, B.L.; Elsayed, S.; Hussain, Z.; Church, D.L.; Gregson, D.B.; Louie, T.; Conly, J.M. New quadriplex PCR assay for detection of methicillin and mupirocin resistance and simultaneous discrimination of Staphylococcus aureus from coagulase-negative staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 4947–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kwiatkowski, P.; Grygorcewicz, B.; Pruss, A.; Wojciuk, B.; Dołęgowska, B.; Giedrys-Kalemba, S.; Sienkiewicz, M.; Wojciechowska-Koszko, I. The effect of subinhibitory concentrations of trans-anethole on antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of mupirocin against mupirocin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019, 25, 1424–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain | Isolation Source | Susceptibility Testing | Phenotypic Resistance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GE | CIP | FOX | E | CC | |||

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 | ATCC (clinical isolate) | R | S | R | R | R | MRSA, cMLSB |

| 1 | Surgical wound | R | R | R | R | R | MRSA, cMLSB |

| 2 | BAL | R | R | R | R | R | MRSA, cMLSB |

| 3 | BAL | R | R | R | R | R | MRSA, cMLSB |

| 4 | Surgical wound | R | R | R | R | R | MRSA, iMLSB |

| 5 | Surgical wound | R | R | R | R | R | MRSA, cMLSB |

| 6 | Urine | R | R | R | R | R | MRSA, cMLSB |

| 7 | Surgical wound | R | R | R | R | R | MRSA, cMLSB |

| 8 | Surgical wound | R | R | R | R | R | MRSA, cMLSB |

| EOC–βLA | MICo | MICc | FIC | FICI | Type of Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methicillin–1,8-Cineole | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | Indifference |

| 1,8-Cineole (mg/mL) | 115.1 ± 0.0 | 115.1 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Methicillin–Eugenol | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.5 | Indifference |

| Eugenol (mg/mL) | 11.1 ± 4.8 | 16.7 ± 0.0 | 1.5 | ||

| Methicillin–Carvacrol | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.4 | Indifference |

| Carvacrol (mg/mL) | 3.2 ± 1.1 | 7.6 ± 0.0 | 2.4 | ||

| Methicillin–Linalool | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | Indifference |

| Linalool (mg/mL) | 6.8 ± 0.0 | 6.8 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Methicillin–Linalyl acetate | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | Synergy |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 46.9 ± 16.3 | 7.0 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | ||

| Methicillin–trans-Anethole | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | Indifference |

| trans-Anethole (mg/mL) | 494.0 ± 0.0 | 494.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Methicillin–Thymol | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 15.6 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | Antagonism |

| Thymol (mg/mL) | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.0 | 3.0 | ||

| Methicillin–Menthone | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 31.3 ± 0.0 | 4.0 | 6.0 | Antagonism |

| Menthone (mg/mL) | 27.9 ± 0.0 | 55.8 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Penicillin G–1,8-Cineole | |||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.05 | 0.1 | Synergy |

| 1,8-Cineole (mg/mL) | 115.1 ± 0.0 | 3.6 ± 0.0 | 0.03 | ||

| Penicillin G–Eugenol | |||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.2 | Indifference |

| Eugenol (mg/mL) | 11.1 ± 4.8 | 8.3 ± 0.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Penicillin G–Carvacrol | |||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.7 | Indifference |

| Carvacrol (mg/mL) | 3.2 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 0.0 | 1.2 | ||

| Penicillin G–Linalool | |||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | Indifference |

| Linalool (mg/mL) | 6.8 ± 0.0 | 6.8 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Penicillin G–Linalyl acetate | |||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | Addition |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 46.9 ± 16.3 | 3.5 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | ||

| Penicillin G–trans-Anethole | |||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.5 | Indifference |

| trans-Anethole (mg/mL) | 494.0 ± 0.0 | 247.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | ||

| Penicillin G–Thymol | |||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.3 | Indifference |

| Thymol (mg/mL) | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.8 | ||

| Penicillin G–Menthone | |||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | Indifference |

| Menthone (mg/mL) | 27.9 ± 0.0 | 27.9 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Strain | EOC–βLA | MICo | MICc | FIC | FICI | Type of Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Methicillin–Linalyl acetate | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 1000.0 ± 0.0 | 500.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | Addition | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 28.2 ± 0.0 | 14.1 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | |||

| Penicillin G–Linalyl acetate | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 125.0 ± 0.0 | 250.0 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | Indifference | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 28.2 ± 0.0 | 56.3 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | |||

| Penicillin G–1,8-Cineole | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 125.0 ± 0.0 | 250.0 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | Indifference | |

| 1,8-Cineole (mg/mL) | 28.8 ± 0.0 | 57.6 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | |||

| 2 | Methicillin–Linalyl acetate | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 1000.0 ± 0.0 | 62.5 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | Synergy | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 112.6 ± 0.0 | 14.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | |||

| Penicillin G–Linalyl acetate | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 31.3 ± 0.0 | 93.9 ± 0.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | Antagonism | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 112.6 ± 0.0 | 225.3 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | |||

| Penicillin G–1,8-Cineole | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 31.3 ± 0.0 | 93.9 ± 0.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | Antagonism | |

| 1,8-Cineole (mg/mL) | 28.8 ± 0.0 | 57.6 ± 4.2 | 2.0 | |||

| 3 | Methicillin–Linalyl acetate | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 1000.0 ± 0.0 | 125.0 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | Synergy | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 112.6 ± 0.0 | 28.2 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | |||

| Penicillin G–Linalyl acetate | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 31.3 ± 0.0 | 62.5 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | Indifference | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 112.6 ± 0.0 | 112.6 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Penicillin G–1,8-Cineole | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 31.3 ± 0.0 | 62.5 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | Antagonism | |

| 1,8-Cineole (mg/mL) | 28.8 ± 0.0 | 86.4 ± 0.0 | 3.0 | |||

| 4 | Methicillin–Linalyl acetate | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 31.3 ± 0.0 | 15.6 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | Addition | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 112.6 ± 0.0 | 56.3 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | |||

| Penicillin G–Linalyl acetate | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.8 | Addition | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 112.6 ± 0.0 | 28.2 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | |||

| Penicillin G–1,8-Cineole | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | Synergy | |

| 1,8-Cineole (mg/mL) | 57.6 ± 0.0 | 7.2 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | |||

| 5 | Methicillin–Linalyl acetate | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 1000.0 ± 0.0 | 500.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | Addition | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 56.3 ± 0.0 | 28.2 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | |||

| Penicillin G–Linalyl acetate | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 125.0 ± 0.0 | 250.0 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | Antagonism | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 56.3 ± 0.0 | 168.9 ± 10.0 | 3.0 | |||

| Penicillin G–1,8-Cineole | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 125.0 ± 0.0 | 250.0 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | Indifference | |

| 1,8-Cineole (mg/mL) | 57.6 ± 0.0 | 115.2 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | |||

| 6 | Methicillin–Linalyl acetate | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.8 | Addition | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 56.3 ± 0.0 | 14.1 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | |||

| Penicillin G–Linalyl acetate | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 | Addition | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 56.3 ± 0.0 | 14.1 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | |||

| Penicillin G–1,8-Cineole | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | Synergy | |

| 1,8-Cineole (mg/mL) | 57.6 ± 0.0 | 7.2 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | |||

| 7 | Methicillin–Linalyl acetate | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 1000.0 ± 0.0 | 250.0 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 | Addition | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 56.3 ± 0.0 | 14.1 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | |||

| Penicillin G–Linalyl acetate | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 31.3 ± 0.0 | 31.3 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | Indifference | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 56.3 ± 0.0 | 56.3 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Penicillin G–1,8-Cineole | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 31.3 ± 0.0 | 31.3 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | Indifference | |

| 1,8-Cineole (mg/mL) | 28.8 ± 0.0 | 57.6 ± 0.0 | 2.0 | |||

| 8 | Methicillin–Linalyl acetate | |||||

| Methicillin (mg/L) | 62.5 ± 0.0 | 15.6 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 | Addition | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 112.6 ± 0.0 | 28.2 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | |||

| Penicillin G–Linalyl acetate | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | Addition | |

| Linalyl acetate (mg/mL) | 112.6 ± 0.0 | 56.3 ± 0.0 | 0.5 | |||

| Penicillin G–1,8-Cineole | ||||||

| Penicillin G (mg/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | Synergy | |

| 1,8-Cineole (mg/mL) | 57.6 ± 0.0 | 14.4 ± 0.0 | 0.3 | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwiatkowski, P.; Łopusiewicz, Ł.; Pruss, A.; Kostek, M.; Sienkiewicz, M.; Bonikowski, R.; Wojciechowska-Koszko, I.; Dołęgowska, B. Antibacterial Activity of Selected Essential Oil Compounds Alone and in Combination with β-Lactam Antibiotics Against MRSA Strains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21197106

Kwiatkowski P, Łopusiewicz Ł, Pruss A, Kostek M, Sienkiewicz M, Bonikowski R, Wojciechowska-Koszko I, Dołęgowska B. Antibacterial Activity of Selected Essential Oil Compounds Alone and in Combination with β-Lactam Antibiotics Against MRSA Strains. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(19):7106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21197106

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwiatkowski, Paweł, Łukasz Łopusiewicz, Agata Pruss, Mateusz Kostek, Monika Sienkiewicz, Radosław Bonikowski, Iwona Wojciechowska-Koszko, and Barbara Dołęgowska. 2020. "Antibacterial Activity of Selected Essential Oil Compounds Alone and in Combination with β-Lactam Antibiotics Against MRSA Strains" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 19: 7106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21197106

APA StyleKwiatkowski, P., Łopusiewicz, Ł., Pruss, A., Kostek, M., Sienkiewicz, M., Bonikowski, R., Wojciechowska-Koszko, I., & Dołęgowska, B. (2020). Antibacterial Activity of Selected Essential Oil Compounds Alone and in Combination with β-Lactam Antibiotics Against MRSA Strains. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(19), 7106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21197106