Exploring the Clinical Applications of Lemongrass Essential Oil: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

3.1. Oromucosal Application

3.1.1. Efficacy in Periodontitis

3.1.2. Efficacy in Gingivitis

3.1.3. Prophylactic Use

3.2. Dermal Application

3.3. Anti-Dandruff Effect

3.4. Safety

3.5. Limitations and Perspectives

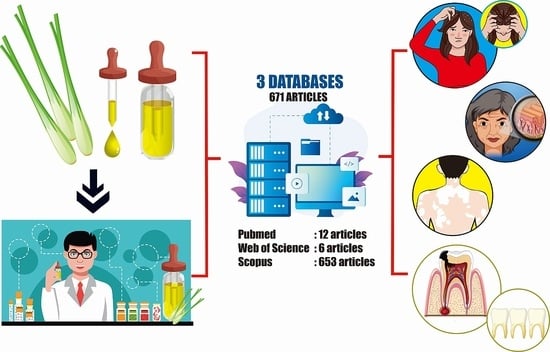

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Search Strategy

4.3. Eligibility Criteria

4.4. Study Selection

4.5. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Padilla-Camberos, E.; Sanchez-Hernandez, I.M.; Torres-Gonzalez, O.R.; Gallegos-Ortiz, M.R.; Méndez-Mona, A.L.; Baez-Moratilla, P.; Flores-Fernandez, J.M. Natural essential oil mix of sweet orange peel, cumin, and allspice elicits anti-inflammatory activity and pharmacological safety similar to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 3830–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhila, A. Essential Oil-Bearing Grasses: The Genus Cymbopogon; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tibenda, J.J.; Yi, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q. Review of phytomedicine, phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology, toxicology, and pharmacological activities of Cymbopogon genus. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 997918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouhan, K.B.S.; Mukherjee, S.; Mahato, K.; Sinha, A.; Mandal, V. An integrated holistic approach to unveil the key operational learnings of solvent-free microwave extraction of essential oil: An effort to dig deep-The case of lemongrass. Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 165, 117131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, E.; Kozłowska, M.; Gruczyńska-Sękowska, E.; Kowalska, D.; Tarnowska, K. Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil: Extraction, composition, bioactivity and uses for food preservation—A review. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019, 69, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisowa, E.H.; Hall, D.R.; Farman, D.I. Volatile constituents of the essential oil of Cymbopogon citratus Stapf grown in Zambia. Flavour Fragr. J. 1998, 13, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, G.; Shri, R.; Panchal, V.; Sharma, N.; Singh, B.; Mann, A.S. Scientific basis for the therapeutic use of Cymbopogon citratus, stapf (Lemon grass). J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2011, 2, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifah, A.M.; Abdalla, S.A.; Dosoky, W.M.; Shehata, M.G.; Khalifah, M.M. Utilization of lemongrass essential oil supplementation on growth performance, meat quality, blood traits and caecum microflora of growing quails. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2021, 66, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, Y.Y.; Zareisedehizadeh, S.; Seetoh, W.G.; Neo, S.Y.; Tan, C.H.; Koh, H.L. Ethnobotanical survey of usage of fresh medicinal plants in Singapore. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 1450–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaduo, N.K.K.; Katerere, D.; Eloff, J.N.; Naidoo, V. Evaluation of six plant species used traditionally in the treatment and control of diabetes mellitus in South Africa using in vitro methods. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureshkumar, J.; Silambarasan, R.; Ayyanar, M. An ethnopharmacological analysis of medicinal plants used by the Adiyan community in Wayanad district of Kerala, India. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 12, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfa, Z.; Chia, C.T.; Rukayadi, Y. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Cymbopogon citratus (lemongrass) extracts against selected foodborne pathogens. Int. Food Res. J. 2016, 23, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Nur Ain, A.H.; Zaibunnisa, A.H.; Halimahton Zahrah, M.S.; Norashikin, S. An experimental design approach for the extraction of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) oleoresin using pressurised liquid extraction (PLE). Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D.; Machado, L.; Bica, C.G.; Machado, A.K.; Steffani, J.A.; Cadoná, F.C. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus (D.C.) Stapf). Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 1474–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhatem, M.N.; Ferhat, M.A.; Kameli, A.; Saidi, F.; Kebir, H.T. Lemon grass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil as a potent anti-inflammatory and antifungal drugs. Libyan J. Med. 2014, 9, 25431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, H.S.; Ali, A.; Zahra, S.; Hassan, Z.U.; Kubra, K.T.; Azam, M.; Zahid, H.F. Phytochemical composition and pharmacological potential of lemongrass (Cymbopogon) and impact on gut microbiota. AppliedChem 2022, 2, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahal, G.; Woerdenbag, H.J.; Hinrichs, W.L.; Visser, A.; Tepper, P.G.; Quax, W.J.; van der Mei, H.C.; Bilkay, I.S. Antifungal and biofilm inhibitory effect of Cymbopogon citratus (lemongrass) essential oil on biofilm forming by Candida tropicalis isolates; an in vitro study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 246, 112188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangalagiri, N.P.; Panditi, S.K.; Jeevigunta, N.L.L. Antimicrobial activity of essential plant oils and their major components. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdana, M.I.; Ruamcharoen, J.; Panphon, S.; Leelakriangsak, M. Antimicrobial activity and physical properties of starch/chitosan film incorporated with lemongrass essential oil and its application. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 141, 110934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdana, M.I.; Panphon, S.; Ruamcharoen, J.; Leelakriangsak, M. Antimicrobial property of cassava starch/chitosan film incorporated with lemongrass essential oil and its shelf life. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 16, 2891–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, B.; Balázs, V.L.; Molnár, S.; Szögi-Tatár, B.; Böszörményi, A.; Palkovics, T.; Horváth, G.; Schneider, G. Antibacterial effect of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) against the aetiological agents of pitted keratolyis. Molecules 2022, 27, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, G.; Steinbach, A.; Putics, Á.; Solti-Hodován, Á.; Palkovics, T. Potential of essential oils in the control of Listeria monocytogenes. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.U.; Lay, H.L.; Wu, M.C. The isolation, structural characterization, and anticancer activity from the aerial parts of Cymbopogon flexuosus. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.K. Ethno-medicinal uses and screening of plants for antibacterial activity from Similipal Biosphere Reserve, Odisha, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Parker, T.L. Lemongrass (Cymbopogon flexuosus) essential oil demonstrated anti-inflammatory effect in pre-inflamed human dermal fibroblasts. Biochim. Open 2017, 4, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, R.; Stringaro, A.; Nicolini, L.; Zanellato, M.; Boccia, P.; Maggi, F.; Gabbianelli, R. Effects of essential oils from Cymbopogon spp. and Cinnamomum verum on biofilm and virulence properties of Escherichia coli O157: H7. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Thorne, R.F.; Zhang, S. Antimicrobial activity of lemongrass essential oil (Cymbopogon flexuosus) and its active component citral against dual-species biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus and Candida species. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 603858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaonkar, R.; Shiralgi, Y.; Lakkappa, D.B.; Hegde, G. Essential oil from Cymbopogon flexuosus as the potential inhibitor for HSP90. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, A.K.; Sharma, S.N.; Tava, A. Composition of Cymbopogon pendulus (Nees ex Steud) wats, an elemicin-rich oil grass grown in Jammu region of India. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1997, 9, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adukwu, E.C.; Bowles, M.; Edwards-Jones, V.; Bone, H. Antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity and chemical analysis of lemongrass essential oil (Cymbopogon flexuosus) and pure citral. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 9619–9627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukarram, M.; Choudhary, S.; Khan, M.A.; Poltronieri, P.; Khan, M.M.A.; Ali, J.; Kurjak, D.; Shahid, M. Lemongrass essential oil components with antimicrobial and anticancer activities. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartatie, E.S.; Prihartini, I.; Widodo, W.; Wahyudi, A. Bioactive compounds of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil from different parts of the plant and distillation methods as natural antioxidant in broiler meat. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 532, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manosroi, J.; Dhumtanom, P.; Manosroi, A. Anti-proliferative activity of essential oil extracted from Thai medicinal plants on KB and P388 cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2006, 235, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Whelan, R.J.; Pattnaik, B.R.; Ludwig, K.; Subudhi, E.; Rowland, H.; Claussen, N.; Zucker, N.; Uppal, S.; Kushner, D.M.; et al. Terpenoids from Zingiber officinale (Ginger) induce apoptosis in endometrial cancer cells through the activation of p53. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e53178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabi, M.F.; Sheikh, B.Y. Anti-proliferative effect and phytochemical analysis of Cymbopogon citratus extract. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 906239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosol, T.J.; Cohen, S.M.; Eisenbrand, G.; Fukushima, S.; Gooderham, N.J.; Guengerich, F.P.; Hecht, S.S.; Rietjens, I.M.C.M.; Davidsen, J.M.; Harman, C.L.; et al. FEMA GRAS assessment of natural flavor complexes: Lemongrass oil, chamomile oils, citronella oil and related flavoring ingredients. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 175, 113697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare. Citronella oil. In European Pharmacopoeia 11.0 01/2008:1609 corrected 7.0; EDQM Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2008; p. 1466. [Google Scholar]

- Api, A.; Belsito, D.; Biserta, S.; Botelho, D.; Bruze, M.; Burton, G.; Buschmann, J.; Cancellieri, M.; Dagli, M.; Date, M.; et al. RIFM fragrance ingredient safety assessment, citral, CAS Registry Number 5392-40-5. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 141, 111339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viktorová, J.; Stupák, M.; Řehořová, K.; Dobiasová, S.; Hoang, L.; Hajšlová, J.; Van Thanh, T.; Van Tri, L.; Van Tuan, N.; Ruml, T. Lemon grass essential oil does not modulate cancer cells multidrug resistance by citral—Its dominant and strongly antimicrobial compound. Foods 2020, 9, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satthanakul, P.; Taweechaisupapong, S.; Paphangkorakit, J.; Pesee, M.; Timabut, P.; Khunkitti, W. Antimicrobial effect of lemongrass oil against oral malodour micro-organisms and the pilot study of safety and efficacy of lemongrass mouthrinse on oral malodour. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 118, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dany, S.S.; Mohanty, P.; Tangade, P.; Rajput, P.; Batra, M. Efficacy of 0.25% lemongrass oil mouthwash: A three arm prospective parallel clinical study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, ZC13–ZC17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akula, S.; Nagarathna, J.; Srinath, S.K. Anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis efficacy of 0.25% lemongrass oil and 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash in children. Front. Dent. 2021, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.F.; Schwiertz, A.; Jentsch, H.F.R. Adjunctive use of essential oils following scaling and root planing –a randomized clinical trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, P.; Gokhale, S.T.; Manjunath, S.; Al-Qahtani, S.M.; Magbol, M.A.; Nagate, R.R.; Tikare, S.; Chaturvedi, S.; Agarwal, A.; Venkataram, V. Comparative evaluation of locally administered 2% gel fabricated from lemongrass polymer and 10% doxycycline hyclate gel as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis—A randomized controlled trial. Polymers 2022, 14, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelapornpisid, P.; Wickett, R.R.; Chansakaow, S.; Wongwattananukul, N. Potential of native Thai aromatic plant extracts in antiwrinkle body creams. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2015, 66, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carmo, E.S.; Pereira, F.d.O.; Cavalcante, N.M.; Gayoso, C.W.; Lima, E.d.O. Treatment of tinea versicolor with topical application of essential oil of Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf-therapeutic pilot study. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2013, 88, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaisripipat, W.; Lourith, N.; Kanlayavattanakul, M. Anti-dandruff hair tonic containing lemongrass (Cymbopogon flexuosus) oil. Complement. Med. Res. 2015, 22, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budala, D.G.; Martu, M.A.; Maftei, G.A.; Diaconu-Popa, D.A.; Danila, V.; Luchian, I. The role of natural compounds in optimizing contemporary dental treatment—Current status and future trends. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warad, S.B.; Kolar, S.S.; Kalburgi, V.; Kalburgi, N.B. Lemongrass essential oil gel as a local drug delivery agent for the treatment of periodontitis. Anc. Sci. Life 2013, 32, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battino, M.; Bompadre, S.; Politi, A.; Fioroni, M.; Rubini, C.; Bullon, P. Antioxidant status (CoQ10 and Vit. E levels) and immunohistochemical analysis of soft tissues in periodontal diseases. Biofactors 2005, 25, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, M.; Grossi, S.G.; Dunford, R.G.; Ho, A.W.; Trevisan, M.; Genco, R.J. Dietary vitamin C and the risk for periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 2000, 71, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasey, F.; Tantray, S.; Ahluwalia, R.; Khan, M.S. Comparative evaluation of 0.25% lemongrass oil mouthwash and 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash in fixed orthodontic patients suffering from gingivitis. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2023, 24, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauber, C.d.S.; Guterres, S.S.; Schapoval, E.E. LC determination of citral in Cymbopogon citratus volatile oil. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2005, 37, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bard, M.; Albrecht, M.R.; Gupta, N.; Guynn, C.J.; Stillwell, W. Geraniol interferes with membrane functions in strains of Candida and Saccharomyces. Lipids 1988, 23, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taweechaisupapong, S.; Ngaonee, P.; Patsuk, P.; Pitiphat, W.; Khunkitti, W. Antibiofilm activity and post antifungal effect of lemongrass oil on clinical Candida dubliniensis isolate. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2012, 78, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Torres, A.G.; López-Castillo, G.N.; Marín-Torres, J.L.; Portillo-Reyes, R.; Luna, F.; Baca, B.E.; Sandoval-Ramírez, J.; Carrasco-Carballo, A. Cymbopogon citratus essential oil: Extraction, GC–MS, phytochemical analysis, antioxidant activity, and in silico molecular docking for protein targets related to CNS. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 5164–5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, A.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Ferreira, N.R.; Silva, A.M.; Nowak, I.; Souto, E.B. Anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activity of citral: Optimization of citral-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) using experimental factorial design and LUMiSizer®. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 553, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Navajas, Y.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Sendra, E.; Perez-Alvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J. In vitro antibacterial and antioxidant properties of chitosan edible films incorporated with Thymus moroderi or Thymus piperella essential oils. Food Control 2013, 30, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawati, I.; Indrayanto, G. Natural antioxidants in cosmetics. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2013, 40, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, S.F.; Rocha, C.; Pinheiro, E.J.; Pereira-Leite, C.; Costa, M.D.C.; Rodrigues, L.M. Revealing the protective effect of topically applied Cymbopogon citratus essential oil in human skin through a contact model. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M. Plant-derived antioxidants: Significance in skin health and the ageing process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lavor, É.M.; Fernandes, A.W.C.; de Andrade Teles, R.B.; Leal, A.E.B.P.; de Oliveira Júnior, R.G.; Gama e Silva, M.; de Oliveira, A.P.; Silva, J.C.; de Moura Fontes Araújo, M.T.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; et al. Essential oils and their major compounds in the treatment of chronic inflammation: A review of antioxidant potential in preclinical studies and molecular mechanisms. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 6468593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galuppi, R.; Aureli, S.; Bonoli, C.; Ostanello, F.; Gubellini, E.; Tampieri, M.P. Effectiveness of essential oils against Malassezia spp.: Comparison of two in vitro tests. Med. Mycol. (Mikol. Lek.) 2010, 17, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Khunkitti, W. In vitro antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of some Cymbopogon species. In Essent Oil-Bear Grasses. The Genus Cymbopogon; Akhila, A., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 167–184. [Google Scholar]

- Sattary, M.; Amini, J.; Hallaj, R. Antifungal activity of the lemongrass and clove oil encapsulated in mesoporous silica nanoparticles against wheat’s take-all disease. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2020, 170, 104696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.; Tran, T.K.N.; Ngo, T.C.Q.; Pham, T.N.; Bach, L.G.; Phan, N.Q.A.; Le, T.H.N. Color and composition of beauty products formulated with lemongrass essential oil: Cosmetics formulation with lemongrass essential oil. Open Chem. 2021, 19, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.A.R.A.; Bidinotto, L.T.; Takahira, R.K.; Salvadori, D.M.F.; Barbisan, L.F.; Costa, M. Cholesterol reduction and lack of genotoxic or toxic effects in mice after repeated 21-day oral intake of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 2268–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadzki, P.; Alotaibi, A.; Ernst, E. Adverse effects of aromatherapy: A systematic review of case reports and case series. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 2012, 24, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Jothiramajayam, M.; Ghosh, M.; Mukherjee, A. Evaluation of toxicity of essential oils palmarosa, citronella, lemongrass and vetiver in human lymphocytes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 68, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, G.; Yousefnia, S.; Angnes, L.; Negahdary, M. Design a PEGylated nanocarrier containing lemongrass essential oil (LEO), a drug delivery system: Application as a cytotoxic agent against breast cancer cells. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 80, 104183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan–a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (Year) | Country and Participants | Study Design | Intervention | Duration of Intervention | Evaluation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satthanakul et al. [41] (2015) | Thailand, 20 healthy volunteers | Double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Group A (n = 10): LGEO (Cymbopogon citratus) mouthrinse 2×/day in the morning and night. Group B (n = 10): placebo mouthrinse 2×/day in the morning and night. | 7 days | The concentration of volatile sulphur compounds in breath measured by halimeter. Organoleptic test using a 9-point hedonic scale. | LGEO reduced concentration of volatile sulphur compounds in breath significantly in comparison with placebo both after 1-min once rinse and 7-days treatment. Participants were more satisfied with the LGEO rinse (overall satisfaction taste, breath freshness). |

| Dany et al. [42] (2015) | India, 60 patients with mild to moderate gingivitis | Double-blinded, randomized, controlled clinical trial | Group A (n = 20): 0.25% LGEO (C. citratus or Cymbopogon flexuosus) mouthwash 2× daily + toothbrushing. Group B (n = 20): 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash 2× daily + toothbrushing. Group C (n = 20): toothbrushing only. | 21 days (follow-up at 14 and 21 days) | Plaque index (PI) and gingival index (GI) scores | PI and GI improved significantly after 14 and 21 days in all groups. A greater reduction in PI and GI score was recorded in the LGEO group after 14 and 21 days, followed by chlorhexidine mouthwash group, followed by oral prophylaxis only group. |

| Akula et al. [43] (2021) | India, 60 healthy children between 9–12 years | Single-blinded, randomized controlled trial | Group A (n = 20): 0.25% LGEO (C. citratus) mouthwash 2× daily. Group B (n = 20): 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash 2× daily. Group C (n = 20): oral prophylaxis alone, n = 20). | 21 days (follow-up after 14 and 21 days) | Plaque pH, plaque index (PI), and gingival index (GI) | Intragroup comparison of PI and GI showed a significant decrease between 14 and 21 days in groups A and B, whereas mean plaque pH increased only in group A at day 21 compared with baseline. Intergroup comparison of the PI scores of the three groups at days 1, 14, and 21 did not show any statistically significant differences, but the mean GI was significantly different among the three groups at days 14 and 21. |

| Azad et al. [44] (2016) | Germany, 46 patients with moderate chronic periodontitis undergoing scaling and root planing | Double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Group A (n = 23): LGEO (C. flexuosus) mouthrinse 2× daily. Group B (n = 23): placebo mouthrinse 2× daily. | 14 days (follow up after 3 and 6 months) | Probing depth (PD), attachment level (AL), bleeding on probing (BOP) and modified sulcus bleeding index (SBI) were measured at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months, and subgingival plaque was assessed for periodontitis-associated bacteria. | AL, PD, BOP, and SBI improved significantly in both groups after 3 and 6 months. AL improved significantly better in the group A after 3 and 6 months. The improvement of BOP was also better in the group A after three months. There was no significant difference between the groups at SBI. Test group had more reduction in Treponema denticola and Fusobacterium nucleatum after 3 months and Tannerella forsythia after 6 months. Prevotella micra and Campylobacter rectus decreased significantly in both groups after 3 months. |

| Mittal et al. [45] (2022) | India, 40 subjects suffering from chronic periodontitis | Double-blinded, randomized controlled trial | Group A (n = 20): 2% LGEO (C. citratus) gel administered into the periodontal pocket after scaling and root planning. Group B (n = 20): 10% doxycycline hyclate gel administered into the periodontal pocket after scaling and root planning. Both groups were advised to use 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthrinse. | 3 months (follow-up after 1 and 3 months) | The clinical assessments of gingival index (GI), plaque index (PI), probing pocket depth (PPD), and clinical attachment level (CAL); colony forming unit (CFU) scores of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Actinomyces naeslundii, and Prevotella intermedia | Both the 2% LGEO gel and 10% doxycycline gel significantly improved clinical mean scores after 1 and 3 months (except PI in the LGEO group) and reduced CFU scores for periodontal pathogens. |

| Leelapornpisid et al. [46] (2015) | Thailand, 29 healthy volunteers | Double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial | All participants used an LGEO (C. citratus) containing body cream and a placebo cream twice daily on the forearm. | 4 weeks | Skin condition was evaluated using the Skin Visiometer and skin moisture was evaluated with the Corneometer® at three test sites (untreated, active-cream, and placebo-cream). | LGEO cream significantly improved surface texture compared to baseline, whereas in case of untreated and placebo-treated surfaces no such effects were observed. Both LGEO cream and placebo improved skin hydration. |

| Carmo et al. [47] (2013) | Brazil, 96 patients diagnosed with pityriasis versicolor | Safety (I) phase: open clinical trial. Efficacy (II) phase: randomized, open clinical trial. | Phase I: 20 patients used an LGEO (C. citratus) shampoo 3× weekly and an LGEO cream 2× daily. Phase II: Group A (n = 30): LGEO shampoo 3× weekly and an LGEO cream 2× daily. Group B (n = 30): ketoconazole shampoo 3× weekly and a ketoconazole cream 2× daily. | 40 days (each phase) | Phase I: adverse reactions Phase II: rate of mycological cure | Phase I showed no adverse events (except one case of burning sensation on the scalp after applying the shampoo). Phase II, LGEO had a 60% mycological cure rate, while ketoconazole had over 80%. Both treatments were effective, however, ketoconazole was significantly more effective. |

| Chaisripipat et al. [48] (2015) | Thailand, 30 healthy volunteers experiencing dandruff | Double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial | Group A (n = 10): application of 5 drops of a head tonic containing 5% LGEO (C. flexuosus) in one side of the head and a placebo hair tonic on the other side of the head, 2× daily. Group B (n = 10): application of 5 drops of a head tonic containing 10% LGEO in one side of the head and a placebo hair tonic on the other side of the head, 2× daily. Group C (n = 10): application of 5 drops of a head tonic containing 15% LGEO in one side of the head and a placebo hair tonic on the other side of the head, 2× daily. | 14 days (follow-up: 7 and 14 days) | Reduction of dandruff using the D-Squame® scale | The application of LGEO hair tonics with 5, 10, or 15% reduced dandruff significantly (p < 0.005) at day 7 (33, 75, and 51%) and increased the effect even more (p < 0.005) at day 14 (52, 81, and 74%). Placebo treatment was less effective, but also showed significant efficacy in groups B and C after 21 days. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kusuma, I.Y.; Perdana, M.I.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Csupor, D.; Takó, M. Exploring the Clinical Applications of Lemongrass Essential Oil: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17020159

Kusuma IY, Perdana MI, Vágvölgyi C, Csupor D, Takó M. Exploring the Clinical Applications of Lemongrass Essential Oil: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2024; 17(2):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17020159

Chicago/Turabian StyleKusuma, Ikhwan Yuda, Muhammad Iqbal Perdana, Csaba Vágvölgyi, Dezső Csupor, and Miklós Takó. 2024. "Exploring the Clinical Applications of Lemongrass Essential Oil: A Scoping Review" Pharmaceuticals 17, no. 2: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17020159

APA StyleKusuma, I. Y., Perdana, M. I., Vágvölgyi, C., Csupor, D., & Takó, M. (2024). Exploring the Clinical Applications of Lemongrass Essential Oil: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceuticals, 17(2), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17020159