Nature-Based Stress Management Course for Individuals at Risk of Adverse Health Effects from Work-Related Stress—Effects on Stress Related Symptoms, Workability and Sick Leave

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.2. Stress Management Interventions

1.3. Nature, Health and Stress

1.4. Aim

- Explore whether participation in a nature-based stress management course (NBSC) can influence and change a negative health trend for individuals with increasing stress-related problems.

- Gain deeper knowledge about how participants experienced and evaluated the nature and garden content in the course.

1.5. Research Questions

- Does participation in the NBSC decrease self-assessed burnout and stress-related symptoms as well as sick leave, and increase self-assessed work ability? (Aim 1)

- Do the participants acquire tools and strategies to better handle stress, and are these tools used after the course? (Aims 1 and 2)

- How did participants experience and evaluate the nature and garden content in the course? (Aim 2)

2. Method

2.1. Recruitment

2.2. Subjects and Dropouts

| Distribution of Participants (Only Women) | All Participants | Interviewees, |

|---|---|---|

| n = 33 | n = 13 | |

| Count (%) | Count (%) | |

| Age | ||

| ≤49 years | 15 (45%) | 7 (54%) |

| ≥50 years | 18 (55%) | 6 (46%) |

| Marital status | ||

| 26 (79%) | 9 (69%) |

| 7 (21%) | 4 (31%) |

| Educational level | ||

| 14 (42%) | 5 (38%) |

| 19 (58%) | 8 (62%) |

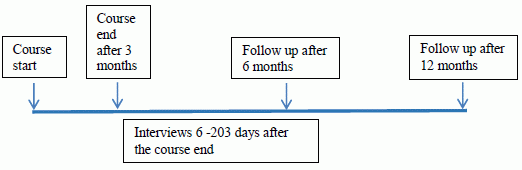

2.3. The Nature-based Stress Management Course

2.4. The Venue

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Quantitative Measures

Primary Measures:

Secondary Measures:

2.5.2. Tools and Strategies for Managing Stress

2.5.3. Qualitative Measure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Qualitative Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Burnout

| Symptoms and Sick Leave | SMBQ | WAI 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 3.75 15 (45%) | ˃ 3.75 18 (55%) | 0–8 23 (74%) | 9–10 8 (26%) | |

| Sleep quality | 7 (47) | 9 (50) | 11 (48) | 4 (50) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 5 (33) | 4 (22) | 5 (22) | 4 (50) |

| Pain in the back, neck, knee, etc. | 5 (33) | 6 (33) | 7 (30) | 3 (38) |

| Headache | 5 (33) | 5 (28) | 8 (35) | 2 (25) |

| Dizziness | 8 (53) | 9 (50) | 11 (48) | 4 (50) |

| Heart palpitations | 7 (47) | 9 (50) | 10 (44) | 6 (75) |

| Sick leave | 6 (40) | 10 (56) | 15 (65) | 0 (n = 7) |

| SMBQ Score | Start | Course End | 6-month Follow-up | 12-month Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| ≤3.75 | 15 (45%) | 16 (48%) | 24 (73%) | 22 (69%) |

| ˃3.75 | 18 (55%) | 17 (52%) | 9 (27%) | 10 (31%) |

| Mean (SD) | 3.82 (1.03) | 3.56 (1.06) | 3.09 (1.21) | 2.93 (1.10) |

3.2. Work Ability and Sick Leave

3.4. Use of New Tools and Strategies for Managing Stress

| Use of New Tools and Strategies n = 33 | Course End Count (%) | 6 Months Count (%) | 12 Months Count (%) | A Selection of Responses from Participants at 12-month Follow-up regarding How Tools/Strategies Help in Stress Management. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of new tools and strategies | ||||

| yes no | 33 (100) 0 | 31 (94) 2 (6) | 31 (94) 2 (6) | |

| Relaxation/Breathing techniques | 23 (67) | 28 (85) | 26 (79) | “I can detect early on when stress takes over—and then withdraw for breathing and mindfulness.” “Focus on breathing and body awareness.” |

| Using gardening/Nature to handle stress | 16 (48) | 8 (24) | 8 (24) | “Nature walks during leisure”. “When stressed, I watch trees and how their leaves are gently blowing.” “With eyes open, see the small things and details in nature.” |

| Say “no”; limiting engagement; taking breaks | 16 (48) | 16 (48) | 20 (61) | “Taking small breaks, daring to say no, letting go of the need to control.” “Listen to signals from my body.” |

3.5. Qualitative Results

3.5.1. Education about Nature and Garden

3.5.2. The Impact of the Environment

3.5.3. Tools and Strategies for Managing Stress

4. Discussion

4.1. Burnout, Work Ability, and Sick Leave

4.2. Health Symptoms and Sleep Quality

4.3. Tools and Strategies for Managing Stress

4.4. The Nature and Garden Content

4.5. Additional Reflections

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stefansson, C.G. Major public health problems—Mental ill-health. Scand. J. Public Health 2006, 34, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Stenbeck, M.; Persson, G. Working life, work environment and health. Scand. J. Public Health 2006, 34, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Social Insurance Agency (Försäkringskassan). Svar på regeringsuppdrag: Sjukfrånvaro i Psykiska Diagnoser. Delrapport. 2013. (in Swedish, Answer to the Government’s Appointments: Absenteeism in Psychiatric Diagnoses Progress Report). Available online: http://www.forsakringskassan.se/wps/wcm/connect/40ab7654-ad14–450b-95c8-d6295f98b420/regeringsuppdrag_sjukfranvaro_i_psykiska_diagnoser_delrapport.pdf?MOD=AJPERES (accessed on 29 September 2013).

- National Board of Health and Welfare. Exhaustion Disorder—Stress-Related Mental Disorders. Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. Available online: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/lists/artikelkatalog/attachments/10723/2003–12318_200312319.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2014).

- Glise, K.; Ahlborg, G., Jr.; Jonsdottir, I.H. Course of mental symptoms in patients with stress-related exhaustion: Does sex or age make a difference? BMC Psychiatry. 2012. Available online: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471–244X/12/18 (accessed on 17 June 2014).

- Danielsson, M.; Heimerson, I.; Lundberg, U.; Perski, A.; Stefansson, C.G.; Åkerstedt, T. Psychosocial stress and health problems: Health in Sweden: The National Public Health Report 2012, Chapter 6. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S. Causes and management of stress at work. Occup. Environ. Medicine 2002, 59, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glise, L.; Hadzibajramovic, E.; Jonsdottir, I.H.; Ahlborg, G., Jr. Self-reported exhaustion: A possible indicator of reduced work ability and increased risk of sickness absence among human service workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Envir. Health 2010, 83, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindegård, A.; Larsman, P.; Hadzibajramovic, E.; Ahlborg, G., Jr. The influence of perceived stress and musculoskeletal pain on work performance and work ability in Swedish health care workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Envir. Health 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, A.E.; Mazzola, J.J.; Bauer, J.; Krueger, J.R.; Spector, P.E. Can work make you sick? A meta analysis of the relationships between job stressors and physical symptoms. Work Stress 2011, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- kerstedt, T.; Knutsson, A.; Westerholm, P.; Theorell, T.; Alfredsson, L.; Kecklund, G. Sleep disturbances, work stress and work hours: A cross-sectional study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schauffeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Klink, J.J.L.; Blonk, R.W.B.; Schene, A.H.; van Dijk, F.J.H. The benefits of interventions for work related stress. Amer. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.M.; Rothstein, H.R. Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: A meta analysis. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkham, M.; Shapiro, D.A. Brief psychotherapeutic interventions for job-related distress: A pilot study of prescriptive and exploratory therapy. Counsel. Psychol. Quart. 1990, 3, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willert, M.V.; Thulstrup, A.M.; Bonde, J.P. Effects of a stress management intervention on absenteeism and return to work—Results from a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2011, 37, 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, A.L.; Strøjer, J.; Ebbehøj, N.E.; Schultz-Larsen, K.; Marott, J.L.; Mortensen, O.S.; Suadicani, P. Multidimensional intervention and sickness absence in assistant nursing students. Occup. Med. 2009, 59, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, A.L.; Marott, J.L.; Suadicani, P.; Mortensen, O.S.; Ebbehøj, N.E. Sickness absence in student nursing assistants following a preventive intervention programme. Occup. Med. 2011, 61, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werneburg, B.L.; Herman, L.L.; Preston, H.R.; Rausch, S.M.; Warren, B.A.; Olsen, K.D.; Clark, M.M. Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary worksite stress reduction programme for women. Stress Health 2011, 27, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterqvist, K.; Maanmies, J.; Strom, L.; Andersson, G. Randomized controlled trial of internet-based stress management. Cognitive Behav. Ther. 2003, 32, 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, G.; Strömgren, T.; Ström, L.; Lyttkens, L. Randomized controlled trial of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for distress associated with tinnitus. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 810–816. [Google Scholar]

- Sakula, A. In search of Hippocrates: A visit to Kos. J. Roy. Soc. Med. 1984, 77, 682–688. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, C.A. The profession of horticultural therapy compared with other allied therapies. J. Ther. Hortic. 2002, 13, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E. Horticultural therapy. JCHI 2003, 7, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Söderback, I.; Söderström, M.; Schälander, E. Horticultural therapy: The “healing garden” and gardening in rehabilitation measures at Danderyd Hospital Rehabilitation Clinic, Sweden. Paediat. Rehabil. 2004, 7, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–442. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.; Losito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Popham, F. Effects of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: An observational population study. Lancet 2008, 372, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarsson, J.J.; Wiens, S.; Nilsson, M.E. Stress recovery during exposure to nature sound and environmental noise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Grahn, P. Stressed individuals’ preference for activities and environmental characteristics in green space. Urban Green 2011, 10, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adevi, A.A.; Grahn, P. Attachment to certain natural environments: A basis for choice of recreational settings, activities and restoration from stress? Environ. Nat Resour. 2011, 1, 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Adevi, A.A. Supportive Nature and Stress: Wellbeing in Connection to Our Inner and Outer Landscape. Doctoral Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lottrup, L.; Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U. Workplace greenery and perceived level of stress: Benefits of access to a green outdoor environment at the workplace. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2013, 110, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennessen, C.; Cimprich, B. Views to nature: Effects on attention. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. Exposure to restorative environments help restore attentional capacity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottosson, J.; Grahn, P. A comparison of leisure time spent in a garden with leisure time spent indoors: On measures of restoration in residents in geriatric care. Landsc. Res. 2005, 30, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.; Kross, E.; Krpan, K.M.; Askren, M.K.; Burson, A.; Deldin, P.J.; Kaplan, S.; Sherdell, L.; Gotlib, I.H.; Jonides, J. Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 140, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottosson, J.; Grahn, P. The role of natural settings in crisis rehabilitation: How does the level of crisis influence the response to experiences of nature with regard to measures of rehabilitation? Landsc. Res. 2008, 33, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.; Martinsen, E.W.; Kirkevold, M. Therapeutic horticulture in clinical depression: A prospective study. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2009, 23, 312–328. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, K.S.A.; Rydstedt, L.W. Active use of the natural environment for emotion regulation. Eur. J. Psychol. 2013, 9, 798–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hartig, T.; Bringslimark, T.; Patil, G. Restorative Environmental Design: What, When, Where, and for Whom? In Bringing Buildings to Life: The Theory and Practice of Biophilic Building Design; Kellert, S.R., Heerwagen, J., Mador, M., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter, U.; Palsdottir, A.M.; Burls, A.; Chermaz, A.; Ferrini, F.; Grahn, P. Nature-based Therapeutic Intervention. In Forests, Trees and Human Health; Nilsson, K., Sangster, M., Gallis, C., Hartig, T., de Vries, S., Seeland, K., Schipperijn, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 309–342. [Google Scholar]

- Grahn, P.; Ivarsson, C.T.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Bengtsson, I.-L. Using Affordances as a Health-promoting Tool in a Therapeutic Garden. In Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health; Thompson, C.W., Bell, S., Aspinall, P., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2010; pp. 116–154. [Google Scholar]

- Melamed, S.; Kushnir, T.; Shirom, A. Burnout and risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Behav. Med. 1992, 18, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Meditation, restoration and the management of mental fatigue. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 480–506. [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag-Öström, E.; Nordin, M.; Slunga-Järvholm, L.; Lundell, Y.; Brännström, R.; Dolling, A. Can the boreal forest be used for rehabilitation and recovery from stress-related exhaustion? A pilot study. Scand. J. Forest. Res. 2011, 26, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A. Burnout in Work Organization. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Cooper, C.L., Robertson, I., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren-Nilsson, A.; Jonsdottir, I.H.; Pallant, J.; Ahlborg, G., Jr. Internal construct validity of the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Questionnaire (SMBQ). BMC Public Health. 2012. Available online: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471–2458/12/1 (accessed on 17 June 2014).

- Perski, A.; Grossi, G. Treatment of patients on long-term sick leave because of stress-related problems: Results from an intervention study. Läkartidningen 2004, 101, 1295–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Grossi, G.; Perski, A.; Evengård, B.; Blomqvist, V.; Orth-Gomér, K. Psychological correlate of burnout among women. J. Psychosom. Res. 2003, 55, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir, I.H.; Rödjer, L.; Hadzibajramovic, E.; Börjesson, M.; Ahlborg, G., Jr. A prospective study of leisure-time physical activity and mental health in Swedish health care workers and social insurance officers. Prev. Med. 2010, 51, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tuomi, K.; Ilmarinen, J.; Jahkola, A.; Katajarinne, L.; Tulkki, A. Work Ability Index, 2nd ed.; Finnish Institute of Occupational Health: Helsinki, Finland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Åkerstedt, M.; Ingre, M.; Broman, J.-E.; Kecklund, G. Disturbed sleep in shift workers, day workers, and insomniacs. Chronobiol. Int. 2008, 25, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, R.G. Improved confidence intervals for the difference between binomial proportions based on paired data. Statist. Med. 1998, 17, 2635–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, P. A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Educ. Today 1991, 11, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M.; Barrett, M.; Mayan, M.; Olson, K.; Spiers, J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Method. 2002, 1, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Arvidson, E.; Börjesson, M.; Ahlborg, G., Jr.; Lindegård, A.; Jonsdottir, I. The level of leisure time physical activity is associated with work ability—A cross sectional and prospective study of health care workers. BMC Public Health 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlin, E.; Matuszczyk, J.V.; Ahlborg, G., Jr.; Grahn, P. How do participants in nature-based therapy experience and evaluate their rehabilitation? J. Ther. Hortic. 2012, 22, 8–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, T.S. Sickness absence and work strain among Danish slaughterhouse workers: An analysis of absence from work regarded as coping behavior. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 1, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- kerstedt, T.; Kecklund, G.; Alfredsson, L.; Selen, J. Predicting long-term sickness absence from sleep and fatigue. J. Sleep Res. 2007, 16, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstedt, M.; Söderström, M.; Åkerstedt, T.; Nilsson, J.; Søndergaard, H.-P.; Aleksander, P. Disturbed sleep and fatigue in occupational burnout. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2003, 32, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Pálsdóttir, A.M.; Grahn, P.; Persson, D. Changes in experienced value of everyday occupations after nature-based vocational rehabilitation. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 21, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ottosson, J.; Grahn, P. Measures of restoration in geriatric care residences. J. Housing Elder. 2006, 19, 229–258. [Google Scholar]

- Pálsdóttir, A.M. The Role of Nature in Rehabilitation for Individuals with Stress-related Mental Disorders: Alnarp Rehabilitation Garden as Supportive Environment. Doctoral Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Sahlin, E.; Ahlborg, G., Jr.; Matuszczyk, J.V.; Grahn, P. Nature-Based Stress Management Course for Individuals at Risk of Adverse Health Effects from Work-Related Stress—Effects on Stress Related Symptoms, Workability and Sick Leave. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 6586-6611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110606586

Sahlin E, Ahlborg G Jr., Matuszczyk JV, Grahn P. Nature-Based Stress Management Course for Individuals at Risk of Adverse Health Effects from Work-Related Stress—Effects on Stress Related Symptoms, Workability and Sick Leave. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014; 11(6):6586-6611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110606586

Chicago/Turabian StyleSahlin, Eva, Gunnar Ahlborg, Jr., Josefa Vega Matuszczyk, and Patrik Grahn. 2014. "Nature-Based Stress Management Course for Individuals at Risk of Adverse Health Effects from Work-Related Stress—Effects on Stress Related Symptoms, Workability and Sick Leave" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11, no. 6: 6586-6611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110606586

APA StyleSahlin, E., Ahlborg, G., Jr., Matuszczyk, J. V., & Grahn, P. (2014). Nature-Based Stress Management Course for Individuals at Risk of Adverse Health Effects from Work-Related Stress—Effects on Stress Related Symptoms, Workability and Sick Leave. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(6), 6586-6611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110606586