The Agreement between Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Assessment of Patients’ Health Literacy—A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Health Literacy

1.2. Measurements of Health Literacy

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Study Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

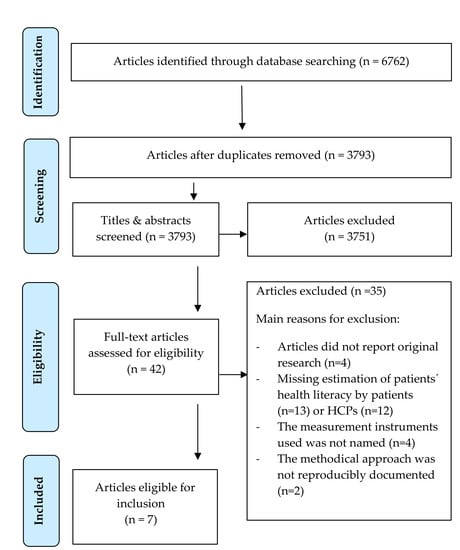

3.1. Search Strategy and Studies

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Assessment of Patients’ HL by Patients and HCPs

3.4. Assessment by Patients and HCPs and The Agreement between Patients’ and HCPs’ HL Assessment

3.5. Factors Associated with (Dis)Agreement in Health Literacy Assessment

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section/Topic | # | Checklist Item | Reported on Page # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both. | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable: background; objectives; data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions; study appraisal and synthesis methods; results; limitations; conclusions and implications of key findings; systematic review registration number. | 1 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. | 2–3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS). | 3 |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (e.g., Web address), and, if available, provide registration information including registration number. | 3 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics (e.g., PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (e.g., years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale. | 3 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources (e.g., databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) in the search and date last searched. | 3 |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 3,Appendix B |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies (i.e., screening, eligibility, included in systematic review, and, if applicable, included in the meta-analysis). | 3–4 |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports (e.g., piloted forms, independently, in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 4 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought (e.g., PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 3 |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis. | 4 |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures (e.g., risk ratio, difference in means). | 4 |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies, if done, including measures of consistency (e.g., I2) for each meta-analysis. | 4 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 | Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence (e.g., publication bias, selective reporting within studies). | 4 |

| Additional analyses | 16 | Describe methods of additional analyses (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression), if done, indicating which were pre-specified. | N/A |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 17 | Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally with a flow diagram. | 5 |

| Study characteristics | 18 | For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted (e.g., study size, PICOS, follow-up period) and provide the citations. | 6/7 |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 | Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome level assessment (see item 12). | 4 |

| Results of individual studies | 20 | For all outcomes considered (benefits or harms), present, for each study: (a) simple summary data for each intervention group (b) effect estimates and confidence intervals, ideally with a forest plot. | 7,10,11 |

| Synthesis of results | 21 | Present results of each meta-analysis done, including confidence intervals and measures of consistency. | 8–14 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 | Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies (see Item 15). | 4 |

| Additional analysis | 23 | Give results of additional analyses, if done (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression [see Item 16]). | N/A |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 24 | Summarize the main findings including the strength of evidence for each main outcome; consider their relevance to key groups (e.g., healthcare providers, users, and policy makers). | 14/15 |

| Limitations | 25 | Discuss limitations at study and outcome level (e.g., risk of bias), and at review-level (e.g., incomplete retrieval of identified research, reporting bias). | 15/16 |

| Conclusions | 26 | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implications for future research. | 16 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 27 | Describe sources of funding for the systematic review and other support (e.g., supply of data); role of funders for the systematic review. | 16 |

Appendix B

| Databases | Synthax |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (health[tiab] AND (literacy[tiab] OR literate[tiab])) AND (nurse[tiab] OR nurses[tiab] OR physician [tiab] OR physicians [tiab] OR doctor [tiab] OR doctors[tiab] OR practitioner[tiab] OR practitioners[tiab] OR “health professional”[tiab] OR “health professionals”[tiab] OR HCP[tiab] OR HCPs[tiab] OR therapist[tiab] OR therapists[tiab] OR physiotherapist [tiab] OR physiotherapists [tiab] OR clinician [tiab] OR clinicians[tiab] OR psychotherapist [tiab] OR psychotherapists[tiab]) AND (patient [tiab] OR patients [tiab]) |

| Scopus | ((Health OR patient) w/2 (literacy OR literate)) AND (nurse OR physician OR doctor OR practitioner OR (health W/2 professional) OR HCP OR therapist OR physiotherapist OR clinician OR psychotherapist) AND Patient |

| PsycINFO (Ovid) | ((Health OR patient) ADJ2 (literacy OR literate)) AND (nurse OR physician OR doctor OR practitioner OR (health ADJ2 professional) OR HCP OR therapist OR physiotherapist OR clinician OR psychotherapist) AND Patient |

| CINAHL | ((Health OR patient) N3 (literacy OR literate)) AND (nurse OR physician OR doctor OR practitioner OR (health N3 professional) OR HCP OR therapist OR physiotherapist OR clinician OR psychotherapist) AND Patient |

| Cochrane | ((Health OR patient) AND (literacy OR literate)) AND (nurse OR physician OR doctor OR practitioner OR (health AND professional) OR HCP OR therapist OR physiotherapist OR clinician OR psychotherapist) AND Patient |

References

- Schaeffer, D.; Hurrelmann, K.; Bauer, U.; Kolpatzik, K. (Eds.) Nationaler Aktionsplan Gesundheitskompetenz. Die Gesundheitskompetenz in Deutschland Stärken; KomPart: Berlin, Germany, 2018. (In Germany) [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam, D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot Int. 1998, 13, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal- a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dehn-Hindenberg, A. Management of chronic diseases. Gesundheitswesen 2013, 75, 623–624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, S.L.; Halpern, D.J.; Viera, A.J.; Berkman, N.D.; Donahue, K.E.; Crotty, K. Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: A systematic review. J. Health Commun. 2011, 16 (Suppl. 3), 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosser, R.N. Literacy and Health status in developing countries. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1989, 10, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schillinger, D.; Grumbach, K.; Piette, J.; Wang, F.; Osmond, D.; Daher, C.; Palacios, J.; Sullivan, G.D.; Bindman, A.B. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA 2002, 288, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cajita, M.I.; Cajita, T.R.; Han, H.R. Health Literacy and Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, D.W.; Parker, R.M.; Clark, W.S. Health literacy and the risk of hospital admission. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1998, 13, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van der Heide, I.; Rademakers, J.; Schipper, M.; Droomers, M.; Sørensen, K.; Uiters, E. Health literacy of Dutch adults: A cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schillinger, D.; Bindman, A.; Wang, F.; Stewart, A.; Piette, J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician–patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2004, 52, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, C.; Lambert, B.L.; Cromwell, T.; Piano, M.R. Nurse overestimation of patients’ health literacy. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18 (Suppl. 1), 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deuster, L.; Christopher, S.; Donovan, J.; Farrell, M. A method to quantify residents’ jargon use during counseling of standardized patients about cancer screening. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 1947–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Castro, C.M.; Wilson, C.; Wang, F.; Schillinger, D. Babel babble: Physicians’ use of unclarified medical jargon with patients. Am. J. Health. Behav. 2007, 31 (Suppl. 1), S85–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessup, R.L.; Osborne, R.H.; Buchbinder, R.; Beauchamp, A. Using co-design to develop interventions to address health literacy needs in a hospitalised population. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coleman, C. Teaching health care professionals about health literacy: A review of the literature. Nurs. Outlook 2011, 59, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, L.; Haun, J.; Sorensen, K.; Valerio, M. Recommendations for advancing health literacy measurement. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18 (Suppl. 1), 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altin, S.V.; Finke, I.; Kautz-Freimuth, S.; Stock, S. The evolution of health literacy assessment tools: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, T.C.; Long, S.W.; Jackson, R.H.; Mayeaux, E.J.; George, R.B.; Murphy, P.W.; Crouch, M.A. Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine: A shortened screening instrument. Fam. Med. 1993, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, P., III; Wilson, J.; Griffith, C. A shortened instrument for literacy screening. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 1036–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, T.C.; Crouch, M.A.; Long, S.W.; Jackson, R.H.; Bates, P.; George, R.B.; Bairnsfather, L.E. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam. Med. 1991, 23, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCormack, L.; Bann, C.; Squiers, L.; Berkman, N.D.; Squire, C.; Schillinger, D.; Ohene-Frempong, J.; Hibbard, J. Measuring health literacy: A pilot study of a new skills-based instrument. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15 (Suppl. 2), 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bann, C.M.; McCormack, L.A.; Berkman, N.D.; Squiers, L.B. The Health Literacy Skills Instrument: A 10-item short form. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17 (Suppl. 3), 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, R.H.; Batterham, R.W.; Elsworth, G.R.; Hawkins, M.; Buchbinder, R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of HLQ. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jordan, J.E.; Osborne, R.H.; Buchbinder, R. Critical appraisal of health literacy indices revealed variable underlying constructs, narrow content and psychometric weaknesses. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormshaw, M.J.; Paakkari, L.T.; Kannas, L.K. Measuring child and adolescent health literacy: A systematic literature review. Health Educ. 2013, 113, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, P., III; Wilson, J.; Griffith, C.; Barnett, D. Residents’ Ability to Identify Patients with Poor literacy Skills. Acad. Med. 2002, 77, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Lindau, S.T.; Basu, A.; Leitsch, S.A. Health Literacy as a Predictor of Follow-Up after an Abnormal Pap Smear. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelly, P.A.; Haidet, P. Physician overestimation of patient literacy: A potential source of health care disparities. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 66, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.D.; Wallace, L.S.; Weiss, B.D. Misperceptions of Medical Understanding in low. Cancer Control 2006, 13, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Storms, H.; Aertgeerts, B.; Vandenabeele, F.; Claes, N. General practitioners’ predictions of their own patients´health literacy. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zawilinski, L.L.; Kirkpatrick, H.; Pawlaczyk, B.; Yarlagadda, H. Actual and perceived patient health literacy: How accurate are residents’ predictions? Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2019, 54, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.W.; Williams, M.V.; Parker, R.M.; Gazmararianc, J.A.; Nurss, J. Develoment of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ. Couns. 1999, 38, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B.D.; Mays, M.Z.; Martz, W.; Castro, K.M.; DeWalt, D.A.; Pignone, M.P.; Mockbee, J.; Hale, F.A. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morris, N.S.; MacLean, C.D.; Chew, L.D.; Littenberg, B. The Single Item Literacy Screener: Evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Fam. Pract. 2006, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röthlin, F.; Pelikan, J.M.; Ganahl, K. Die Gesundheitskompetenz der 15-jährigen Jugendlichen in Österreich. In Abschlussbericht der Österreichischen Gesundheitskompetenz Jugendstudie im Auftrag des Hauptverbands der österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger (HVSV); Ludwig Boltzmann Institut Health Promotion Research (LBIHPR): Wien, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brega, A.G.; Barnard, J.; Mabachi, N.M.; Weiss, B.D.; DeWalt, D.A.; Brach, C.; Cifuentes, M.; Albright, K.; West, D.R. Use the Teach-Back Method: Tool 5. In AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kountz, D.S. Strategies for improving low health literacy. Postgrad. Med. 2009, 121, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toronto, C.E.; Weatherford, B.J. Health Literacy Education in Health Professions Schools: An Integrative Review. Nurs. Educ. 2015, 54, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, C.; Palesy, D.; Lewis, J. Systematic Review and Conceptual Framework for Health Literacy Training in Health Professions Education. Health Prof. Educ. 2019, 5, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaper, M.S.; Winter, A.F.; Bevilacqua, R.; Giammarchi, C.; McCusker, A.; Sixsmith, J.; Koot, J.A.; Reijneveld, S.A. Positive Outcomes of a Comprehensive Health Literacy Communication Training for Health Professionals in Three European Countries: A Multi-centre Pre-post Intervention Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaper, M.S.; Reijneveld, S.A.; van Es, F.D.; de Zeeuw, J.; Almansa, J.; Koot, J.A.; de Winter, A.F. Effectiveness of a Comprehensive Health Literacy Consultation Skills Training for Undergraduate Medical Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kripalani, S.; Weiss, B.D. Teaching about health literacy and clear communication. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 888–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogrodnick, M.M.; Feinberg, I.; Tighe, E.; Czarnonycz, C.C.; Zimmerman, R.D. Health-Literacy Training for First-Year Respiratory Therapy Students: A Mixed-Methods Pilot Study. Respir. Care 2020, 65, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, O.; Vandenberg, A.; May, M.E. Provider and patient perception of psychiatry patient health literacy. Pharm. Pract. 2017, 15, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hawkins, M.; Gill, S.D.; Batterham, R.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. The Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) at the patient-clinician interface: A qualitative study of what patients and clinicians mean by their HLQ scores. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Hara, J.; Hawkins, M.; Batterham, R.; Dodson, S.; Osborne, R.H.; Beauchamp, A. Conceptualisation and development of the Conversational Health Literacy Assessment Tool (CHAT). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Exclusion Criteria: Title and Abstract Screening (Screening Stage) | |

|---|---|

| EC 1 | Participants were not at least 18 years old. |

| EC 2 | Studies did not report original research. |

| EC 3 | Studies did not assess health literacy. |

| EC 4 | Studies did not use a quantitative approach for the estimation of HL. |

| EC 5 | Patients were not involved in the assessment of HL. |

| EC 6 | HCPs were not involved in the assessment of HL. |

| Inclusion Criteria: Full-Text Screening (Eligibility Stage) | |

| Article Requirements | |

| IC 1 | Studies were published in a peer reviewed journal. |

| IC 2 | Studies reported original research. |

| IC 3 | The methodology was reproducibly documented. |

| Assessment Requirements | |

| IC 4 | Studies addressed the analysis of agreement between patients’ HL assessment by patients and HCPs (i.e., providers that are in direct contact with patients). |

| IC 5 | Patients (self- assessment) and HCPs (proxy assessment) assessed the same patient sample. |

| IC 6 | HCP-rated patients’ HL measurement: HCPs assessed patients´ HL needs. |

| IC 7 | Self-reported patients’ HL measurement: Studies used a standardized measurement of patients’ HL. |

| Author, Year, [Ref] | Area | Study Design | Aim/Objective | Setting | Number of Patients | Characteristics of HCPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bass et al., 2002, [28] | USA | Cross-sectional | To determine whether residents could identify patients with poor literacy skills based on clinical interactions during a continuity of care clinic visit. | Hospital-based care; (Internal medicine) | n = 182 | Physicians n = 45 |

| Dickens et al., 2013, [13] | USA | Cross-sectional | To compare nurses’ estimate of a patient’s HL to the patient’s HL. | Hospital-based care (Cardiac units) | n = 65 | Nurses n = 30 |

| Kelly & Haidet, 2007, [30] | USA | Cross-sectional | To investigate physician overestimation of patient literacy level in a primary care setting. | Primary care, Veterans Affairs Medical Center | n = 100 | Physicians n = 12 |

| Lindau et al., 2006, [29] | USA | Prospective | To examine the hypothesis that literacy predicts patient adherence to follow-up recommendations after an abnormal papsmear. | Primary care; Medical Center (HIV Obstetrics/ Gynaecology) | n = 68 | Physicians n = 32 |

| Rogers et al., 2006, [31] | USA | Cross-sectional | To determine whether primary care physicians can accurately identify patients who have limited understanding of medical information based solely on their clinical interactions with patients during an office visit. | Primary care (Family medicine) | n = 140 | Physicians; n = 8 (second-year), n = 10 (third-year) |

| Storms et al., 2019, [32] | Bel-gium | Cross-sectional | To explore the agreement between patients’ HL and GPs’ HL estimations thereof, as well as to examine characteristics impacting this HL (dis)agreement. | Primary care (General practice) | n = 1469 (n = 1375 for analysis) | Physicians n = 80 |

| Zawilinski et al., 2019, [33] | USA | Cross-sectional | To replicate and extend the findings of previous research by examining residents’ ability to predict HL levels in patients and to use a newer validated measure of HL. | Hospital-based care (Internal Medicine, Obstetrics/Gynaecology) | n = 38 | Physicians n = 20 |

| Author, Year [Ref] | HL Instrument–Patients | Questions/HL Instrument and HL Categories–HCPs | HL Categories–Patients | HL Assessment by Patients | HL Estimation by HCPs | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bass et al. 2002 [28] | REALM-Ra | “Do you feel this patient has a literacy problem?”; HCPs answered with “yes. (=Inadequate HL)” or “no. (=Adequate HL)”. | Inadequate HL: Scoring > −6; Adequate HL: Scoring > −7 | n = 74 (36%); n = 108 (59%) | n = 18 (10%); n = 164 (90%) | Overestimation by HCPs: n = 59 (36%); Underestimation by HCPs: n = 3 (17%); Agreement: continuity-adjusted chi-square [(1 df) = 13.18, p < 0.001] |

| Dickens et al. 2013 [13] | NVSb, SILSc | NVS: High likelihood of limited literacy: “Does your patient have low health literacy?”; Possibility of limited literacy: “Does your patient have marginal health literacy?”; Almost always adequate literacy: “Does your patient have adequate health literacy?” | NVS: High likelihood of limited literacy, Possibility of limited literacy, Almost always adequate literacy; SILS: Inadequate HL: 1 (not at all), 2 (a little bit), 3 (somewhat); Adequate HL: 4 (quite a bit), 5 (extremely) | NVS: n = 41 (63%); n = 10 (15%); n = 14 (22%) SILS: n = 35% n = 65% | NVS: n = 19%, n = 13%, n = 68% | Overestimation by HCPs: n = 14 (22%); Agreement: kappa statistic, κ = 0.09 |

| Kelly & Haidet 2007 [30] | REALMd | Scale corresponding to the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) | Level 1: 3rd grade and below; Level 2: 4th–6th grade: Level 3: 7th–8th grade; Level 4: High school | n = 4 (4%), n = 11 (11%), n = 47 (47%), n = 38 (38%) | Level 4: n = 74 (74%) | Overestimation by HCPs: n = 25 (25%), Underestimation by HCPs: n: n = 15 (15%); Agreement: kappa statistic, κ = 0.19 (p < 0.01), Level 1: 0.00, Level 2: 0.29, Level 3: 0.19, Level 4: 0.85, all levels: 0.61 |

| Lindau et al. 2006 [29] | REALMd | Self-administeredquestionnaire: ‘‘Based on your interaction today, what is your estimate of your patient’s reading level?’’ | Adequate (REALM ≥ 61 or high school level) or Inadequate (REALM ≤ 60 or below high school level) | n = 24 (35%), n = 44 (65%) | n = 23 (41%), n = 33 (59%) | Agreement: kappa statistic, κ = 0.43 (p = 0.0006) |

| Rogers et al. 2006 [31] | S-TOFHLAe | “What is your perception of the patient’s medical understanding?”, 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very poor understanding) to 5 (superior understanding). | Inadequate HL: 0–16, Marginal HL: 17–22, Adequate HL: 23–36 | n = 34 (24%), n = 106 (76%) | n = 42 (30%), n = 98 (70%) | Overestimation by HCPs: n = 18 (53%) Underestimation by HCPs: n = 26 (25%) |

| Storms et al., 2019 [32] | HLS-EU-Q 16f | HCPs were restricted to indicating that their patients’ HL was inadequate, problematic, or adequate HL on a simple scale. | 4-point Likert scale (very difficult; difficult; easy; and very easy). These scores were dichotomized. Inadequate HL: 0–8, Problematic HL: 9–12, Adequate HL: 13–16 | n = 201 (15%), n = 299 (22%), n = 875 (64%) | n = 1241 (90%), n = 130 (10%), n = 4 (<1%) | Overestimation by HCPs: n = 199 + 271/1375 (34%), Underestimation by HCPs: n = 68/1375 (5%); Agreement: kappa statistic, κ = 0.033, 95% CI, 0.00124 to 0.0648, p < 0.05; Correct estimation by HCPs: n = 837 (61%); |

| Zawilinski et al., 2019 [33] | HLSI-SFg | Resident Questionnaire (RQ): “Does the patient have a health literacy problem?”, “What is the patient’s level of health literacy?”,“Did patient’s health literacy impact the visit?”; Question 1+3: “yes,” “no,” or “not sure”, Question 2: “inadequate,” “adequate,” or “not sure” | Each correct response was given 1 point. Adequate HL: 7-10, Inadequate HL: 0-6 | n = 21 (55%), n = 17 (45%) | n = 25 (66%), n = 13 (34%) | Overestimation by HCPs: n = 10 (58%), Underestimation by HCPs: n = 6 (29%); Agreement: kappa statistic, κ = 0.13, p = 0.42 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Voigt-Barbarowicz, M.; Brütt, A.L. The Agreement between Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Assessment of Patients’ Health Literacy—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072372

Voigt-Barbarowicz M, Brütt AL. The Agreement between Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Assessment of Patients’ Health Literacy—A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(7):2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072372

Chicago/Turabian StyleVoigt-Barbarowicz, Mona, and Anna Levke Brütt. 2020. "The Agreement between Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Assessment of Patients’ Health Literacy—A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 7: 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072372

APA StyleVoigt-Barbarowicz, M., & Brütt, A. L. (2020). The Agreement between Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Assessment of Patients’ Health Literacy—A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072372