‘Beyond Cancer’ Rehabilitation Program to Support Breast Cancer Survivors to Return to Health, Wellness and Work: Feasibility Study Outcomes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Barriers to Returning to Sustainable Work for Women with Breast Cancer

1.2. The Need for RTW Support Interventions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Proposed Sample

- Working prior to diagnosis and treatment, but not yet RTW at full capacity;

- Ready to participate in the intervention in the context of their general health and other circumstances in order to build their ‘work-readiness’ (note that this was difficult to determine as perceptions of readiness varied greatly across individuals and were not clearly associated with a particular stage of rehabilitation).

2.2. Review of Patient Case Notes

2.3. Historical Control Group

2.4. Beyond Cancer Intervention

2.4.1. Intervention Development

2.4.2. Beyond Cancer Program—Overview of Content and Delivery Framework

2.5. Feasibility Analysis

- To evaluate the recruitment capability and resultant sample characteristics;

- To evaluate and refine data collection procedures and outcome measures;

- To evaluate the acceptability and suitability of the intervention;

- To evaluate the resources and ability to manage and implement the study and the intervention;

- To provide a preliminary evaluation of participant responses to the intervention.

2.6. Expected Outcomes

2.6.1. Return to Work Outcome

2.6.2. Perceived Support at Work Outcome

2.6.3. Work Capacity Change

2.6.4. Acceptability and Perceived Effectiveness from the Employer Perspective

2.7. Post-Intervention Survey

2.8. Interviews and Focus Groups

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment: Capability

3.2. Recruitment: Sample Characteristics

- Capacity, i.e., major health setbacks and/or treatment barriers (e.g., impending surgery, etc.), not ready for rehabilitation (n = 15);

- Secondary and significant mental health barriers (n = 3);

- Self-managing well, services not required (n = 4);

- Lack of engagement with program, not due to primary condition/treatment (n = 7).

3.3. Data collection and Outcome Measures

- Suitability of the primary RTW outcome measure;

- Secondary outcome measures: incomplete data set.

3.3.1. Suitability of Primary RTW Outcome Measure

3.3.2. Appropriateness of Secondary Outcome Measures

“I just find that it is a different situation having cancer than recovering from an injury from the employer’s perspective..… employers are generally really super supportive of employees with cancer to get back to work.” (Beyond Cancer Consultant);

“I didn’t feel like I needed to [engage with the employer support component]. I am sure some people do, but I’m very blessed to be working in the […] sector and they’re very supportive.” (Breast cancer survivor).

3.3.3. Acceptability and Perceived Effectiveness from the Employer Perspective

3.3.4. Incomplete Data Set for Secondary Psychosocial Outcome Variables

3.4. Intervention Acceptability and Suitability

3.4.1. Participant Engagement

- The average program duration was 33 weeks.

- Only 31% (n = 17) of program participants completed the program within the proposed upper limit of 26 weeks due to a combination of treatment/health-related intermission periods, and delays associated with COVID-19 restrictions.

- Forty-three of fifty-five (78.2%) showed evidence of participating in at least two of the components of the Beyond Cancer program (e.g., RTW support plus Positivum health coaching); n = 15 showed evidence of engaging in two elements, n = 19 in three elements, and n = 9 in four elements of the intervention.

- The most commonly utilised program element across all 55 program participants was the occupational rehabilitation RTW planning and monitoring services (n = 39 of 55, 71%), followed by Positivum: cancer health coaching (35 of 55, 64%) and exercise physiology (n = 26 of 55, 47%).

- Only 11 of 55 (20%) chose to engage in the employer education/liaison service provision as a defining feature of the Beyond Cancer program.

3.4.2. Evaluation of the Program

- The multimodal nature of the program;

- The focus was holistic and about building work readiness (as opposed to solely RTW);

- The flexible delivery and tailoring to an individual;

- The support, respect and understanding from consultants;

- The utility of the health coaching in identifying key barriers and building work readiness.

3.5. Intervention Resources and Ability to Manage and Implement the Study and Intervention

- The difficulty surrounding the timing of referral and when to offer the particular components of the program; this is difficult to get right as the right time varies considerably from one cancer survivor to the next;

- The effectiveness of the consultant training; some found themselves in situations where they felt underprepared, especially regarding emotionally-laden or sensitive topics;

- The potential for additional education and feedback for the life insurance case managers.

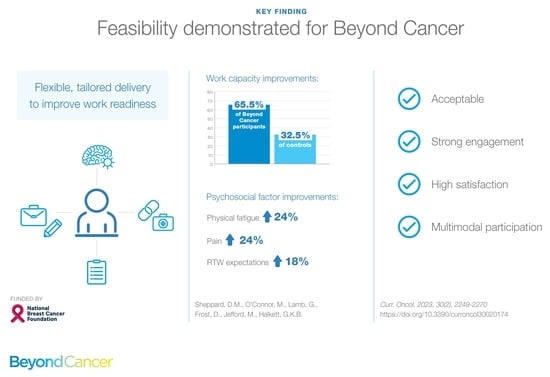

3.6. Preliminary Evaluation of Participant Responses to the Intervention

- Energy levels (physical fatigue symptom severity);

- Pain (current levels of pain and interference);

- Expectations (i.e., confidence that they will be working in the near future);

- Health beliefs (i.e., beliefs about the impact of cancer and treatment on the ability to work);

- General health (perceptions of general health and quality of life).

4. Discussion

4.1. What Went Well

4.2. Challenges, Learnings and Recommendations

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Feasibility Study Implications

4.5. Emerging Recommendations for Beyond Cancer

- Moving forward, ensure that adequate care and consideration is given to the timing of referral to services with respect to the cancer survivor ‘journey’ as this can influence engagement; develop ‘case studies’ to demonstrate how timing can positively and negatively influence engagement and use these cases in consultant training;

- Provide an improved resource package to those referring to facilitate a clearer understanding of the aims of the program and better-informed referring;

- Provide more regular communication with referrers to maintain open lines of communication, including more regular updates on cohort progress with attaining program outcomes or goals;

- Further strengthen the consultant training, particularly having more practice in the delivery of unique program components and using scenario-based learning. While there was no negative feedback from those who attended training online (a handful of consultants were from remote locations such as the Northern Territory or Tasmania, and could only attend online), this type of training is likely to be more effective in person;

- Consider additional content to be added to the health coaching as recommended by the cancer survivor participants, e.g., dietary information, content to tackle cancer-related stigmas.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Cancer in Australia 2019; Cancer Series no119; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Cancer in Australia 2021; Cancer Series no133; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2021.

- De Angelis, R.; Sant, M.; Coleman, M.P.; Francisci, S.; Baili, P.; Pierannunzio, D.; Trama, A.; Visser, O.; Brenner, H.; Ardanaz, E.; et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: Results of EUROCARE-5-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickman, P.W.; Adami, H.O. Interpreting trends in cancer patient survival. J. Intern. Med. 2006, 260, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annual Report 2015/2016. Cancer Council NSW. Available online: https://www.cancercouncil.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/16080_CA_CAN2062_AnnualReport_2016_PRINT2_WEB-LR.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program. National Cancer Institute; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/ (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Jefford, M.; Ward, A.C.; Lisy, K.; Lacey, K.; Emery, J.D.; Glaser, A.W.; Cross, H.; Krishnasamy, M.; McLachlan, S.-A.; Bishop, J. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivors: A population-wide cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer 2017, 25, 3171–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiedtke, C.; Donceel, P.; de Rijk, A.; de Casterle, B.D. Return to work following breast cancer treatment: The employers’ side. J. Occ. Rehab. 2014, 24, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-Y.; Chen, W.-L.; Wu, W.-T.; Lai, C.-H.; Ho, C.-L.; Wang, C.-C. Return to work and mortality in breast cancer survivors: A 11-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Council Australia. Working with Cancer: A Workplace Resource for Leaders, Managers, Trainers and Employees; Cancer Council Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2006.

- Taskila, T.K.; de Boer, A.G.E.M.; Van Dijk, F.J.H.; Verbeek, J.H. Fatigue and its correlates in cancer patients who had returned to work—A cohort study. In Proceedings of the First Scientific Conference on Work Disability Prevention and Integration, Angers, France, 2–3 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tiedtke, C.; de Rijk, A.; Dierckx de Casterle, B.; Christiaens, M.R.; Donceel, P. Experiences and concerns about ‘returning to work’ for women breast cancer survivors: A literature review. Psychooncology 2010, 19, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meixner, E.; Sandrini, E.; Hoeltgen, L.; Eichkorn, T.; Hoegen, P.; König, L.; Arians, N.; Lischalk, J.W.; Wallweiner, M.; Weis, I.; et al. Return to work, fatigue and cancer rehabilitation after curative radiotherapy and radiochemotherapy for pelvic gynecologic cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, L.-A.; Hossan, S.Z. The psychological distress and quality of life of breast cancer survivors in Sydney, Australia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urquhart, R.; Scruton, S.; Kendell, C. Understanding cancer survivors’ needs and experiences returning to work post-treatment: A longitudinal qualitative study. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3013–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, A.G.E.M.; Taskila, T.K.; Tamminga, S.J.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; Feuerstein, M.; Verbeek, J.H. Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 16, CD007569. [Google Scholar]

- Mehnert, A.; de Boer, A.G.E.M.; Feuerstein, M. Employment challenges for cancer survivors. Cancer 2013, 119 (Suppl. S11), 2151–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.L.; Du, R.; Powell, T.; Hobbs, K.L.; Amick, B.C. Characterizing cancer and work disparities using electronic health records. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, H.; Friedrich, M.; Sender, A.; Richter, D.; Geue, K.; Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A.; Leuteritz, K. Work ability and cognitive impairments in young adult cancer patients: Associated factors and changes over time-results from the AYA-Leipzig study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2022, 16, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, A.G.; Decker, R.E.; Namazi, S.; Cavallari, J.M.; Bellizzi, K.M.; Blank, T.O.; Dornelas, E.A.; Tannenbaum, S.H.; Shaw, W.S.; Swede, H.; et al. Perceptions of clinical support for employed breast cancer survivors managing work and health challenges. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 15, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimprich, B.; Janz, N.K.; Northouse, L.; Wren, P.A.; Given, B.; Given, C.W. Taking CHARGE: A self-management program for women following breast cancer treatment. Psychooncology 2005, 14, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, F.; Haslam, C.; Munir, F.; Pryce, J. Returning to work following cancer: A qualitative exploratory study into the experience of returning to work following cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2007, 16, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiedtke, C.; Dierckx de Casterle, B.; Donceel, P.; de Rijk, A. Workplace support after breast cancer treatment: Recognition of vulnerability. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 1770–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijts, S.F.A.; van Egmond, M.P.; Gits, M.; van der Beek, A.J.; Bleiker, E.M. Cancer survivors’ perspectives and experiences regarding behavioral determinants of return to work and continuation of work. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 2164–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, M.C.; Todd, B.L.; Chen, R.; Feuerstein, M. Function and friction at work: A multidimensional analysis of work outcomes in cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014, 8, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.; Mackenzie, L.; Black, D. Workforce participation of Australian women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, K.D.; Forcino, R.C.; Rotenberg, S.; Schiffelbein, J.E.; Morrissette, K.J.; Godzik, C.M.; Lichtenstein, J.D. "The last thing you have to worry about": A thematic analysis of employment challenges faced by cancer survivors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, K.R.; So, W.-Y.; Jang, S. Effects of a post-traumatic growth program on young Korean breast cancer survivors. Healthcare 2023, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algeo, N.; Bennett, K.; Connolly, D. Prioritising the content and delivery of a work-focused intervention for women with breast cancer using the nominal group technique. Work 2022, 73, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.; Di Meglio, A.; Menvielle, G.; Arvis, J.; Bourmaud, A.; Michiels, S.; Pistilli, B.; Vaz-Luis, I.; Dumas, A. Informing the development of multidisciplinary interventions to help breast cancer patients return to work: A qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 8287–8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.M.; Arora, N.K.; Bradley, C.J.; Brauer, E.R.; Graves, D.L.; Lunsford, N.B.; McCabe, M.S.; Nasso, S.F.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Rowland, J.H.; et al. Long-term survivorship care after cancer treatment—Summary of a 2017 national cancer policy forum workshop. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SwissRe. Rehabilitation Watch 2016; SwissRe: Sydney, Australia, 2017; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein, M. Work in cancer survivors: A model for practice and research. J. Cancer Surviv. 2010, 4, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiron, H.A.M.; Crutzen, R.; Godderis, L.; Van Hoof, E.; De Rijk, A. Bridging health care and the workplace: Formulation of a return-to-work intervention for breast cancer patients using an intervention mapping approach. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2016, 26, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. Br. Med. J. 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.M.; Frost, D.; Jefford, M.; O’Connor, M.; Halkett, G. ‘Beyond Cancer’: A study protocol of a multimodal occupational rehabilitation programme to support breast cancer survivors to return to work. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e032505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsmond, G.I.; Cohn, E.S. The distinctive features of a Feasibility Study: Objectives and guiding questions. OTJR Occup. Part. Health. 2015, 35, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.J.; Kreuter, M.; Spring, B.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Linnan, L.; Weiner, D.; Bakken, S.; Kaplan, C.P.; Squiers, L.; Fabrizio, C.; et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, S.W.; van Amstel, F.K.P.; Ottevanger, P.B.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Prins, J.B. The Cancer Empowerment Questionnaire: Psychological empowerment in breast cancer survivors. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2013, 31, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, R.E.; Elsworth, G.R.; Whitfield, K. The Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ): An outcomes and evaluation measure for patient education and self-management interventions for people with chronic conditions. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 66, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nili, A.; Tate, M.; Johnstone, D. A framework and approach for analysis of focus group data in information systems research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2017, 40, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat: European Commission. NACE Rev. 2—Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Modified Monash Model. Australian Government: Department of Health and Aged Care. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/rural-health-workforce/classifications/mmm (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Fitch, M.I.; Nicoll, I. Returning to work after cancer: Survivors’, caregivers’, and employers’ perspectives. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greidanus, M.A.; de Boer, A.; Tiedtke, C.M.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; de Rijk, A.E.; Tamminga, S.J. Supporting employers to enhance the return to work of cancer survivors: Development of a web-based intervention (MiLES intervention). J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greidanus, M.A.; Tamminga, S.J.; de Rijk, A.E.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; de Boer, A. What employer actions are considered most important for the return to work of employees with cancer? A Delphi Study among employees and employers. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2019, 29, 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, K.S.; Momsen, A.H.; Stapelfeldt, C.M.; Nielsen, C.V. Reintegrating employees undergoing cancer treatment into the workplace: A qualitative study of employer and co-worker perspectives. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2019, 29, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.M.; Frost, D.; Jefford, M.; O’Connor, M.; Halkett, G. Building a novel occupational rehabilitation program to support cancer survivors to return to health, wellness and work in Australia. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olischläger, D.L.T.; den Boer, L.X.Y.; de Heus, E.; Brom, L.; Dona, D.J.S.; Klümpen, H.-J.; Stapelfeldt, C.M.; Duijts, S.F.A. Rare cancer and return to work: Experiences and needs of patients and (health care) professionals. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Feasibility Study Question(s) | Data Source/Collection Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1A. Recruitment: capability | How suitable were the referral sources: consider system structures, funding models and processes? | Numbers recruited vs anticipated; consultant focus group data; research meeting notes |

| 1B. Recruitment: sample characteristics | Are participants appropriate? Do the cohort characteristics suggest it is representative? | Sample characteristics relative to historical control group; review eligibility criteria, reasons for dropping out/discontinuing |

| 2. Data collection and outcome measures | How appropriate are data collection procedures and outcome measures? | Consultant focus group data; completeness of data set; research team meeting notes |

| 3. Acceptability and suitability | Are the study procedures and intervention suitable/acceptable? Are there positive perceptions from the participant perspective? | Participant engagement data; participant interview data and survey responses; consultant focus group data |

| 4. Resources and implementation | Was the intervention implemented as designed? Were resources adequate, including funding, time, training? | Participant interview data and survey responses; consultant focus group data |

| 5. Preliminary participant responses | Are the preliminary outcomes promising or indicative of effectiveness? | Quantitative RTW outcomes and psychosocial assessment outcome data |

| Beyond Cancer Breast Cancer Survivor Cohort | Historical Control Group: Cancer Survivor Cohort | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample size (n) | n = 84 TOTAL n = 84 (100%) breast cancer | n = 80 TOTAL n = 36 (45.0%) breast cancer n = 4 (5.0%) colorectal cancer n = 6 (7.5%) ‘multilocation’ cancer n = 4 (5.0%) leukaemia n = 3 (3.75%) lymphoma n = 4 (5.0%) prostate cancer n = 6 (7.5%) head and neck cancer n = 17 (21.25%) other cancers (e.g., kidney, brain, stomach, melanoma) |

| Mean age (St Dev; Range) No. aged ≥ 60 years No. aged 65+ years | 50.81 years (8.24; 33–67 years) n = 10 (11.9%) n = 2 (2.4%) | 50.10 years (9.30; 23–71 years) n = 11 (13.75%) n = 3 (3.75%) |

| Program duration, weeks (St Dev; Range) | 33.4 (17.91; 11.7–88.3 weeks) * | 31.7 (22.97; 9.0–132.4 weeks) |

| Occupation Group | Number of Participants | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Education | 22 | 26.5% |

| Health | 19 | 22.9% |

| Public administration/ defence | 5 | 6.0% |

| Financial services | 5 | 6.0% |

| Wholesale/retail/food/accommodation | 12 | 14.5% |

| Other: Admin/clerical/management/telecommunications | 20 | 24.1% |

| TOTAL | 83 | 100% |

| Theme | Representative Quote |

|---|---|

| Program feedback | |

| Perceived benefits of the multi-modal nature (consultant perspective: focus group) Benefits extended beyond RTW goals (participant perspective: interviews) | [the program] “really was a multi-faceted, sort of, approach and worked really well”. (Consultant) “having those face to face discussions were really invaluable…just being able to go meet with someone in person” (Breast cancer survivor) |

| Perceived benefits of flexible delivery and tailoring (consultant perspective: focus group) | “I think the program is so great and ultimately the best rehab is achieved when we can tailor the service to each member …” (Consultant) |

| Thankful for support and understanding (survey, participant perspective: interviews) | “a lovely lady…one of the most beautiful I have met”; “I really did [feel supported]” (Breast cancer survivor) |

| Highly recommend Beyond Cancer (participant perspective: interviews) | “I would fully recommended it to anyone…I didn’t really want to go at beginning. I just thought it would be irrelevant and, you know…just another appointment to go to. But it was so worthwhile,……it really helped me so much” (Breast cancer survivor) |

| Program feedback specific to health coaching | |

| Perceived value of health coaching in building work readiness (consultant perspective: focus group) | “general strategies to assist with the management of fatigue in their everyday lives, not necessarily at work…” (Consultant) “the health coaching is what we focused on and she found it useful in terms of building confidence and increasing goal-directed behaviours” (Consultant) |

| Other benefits: general emotional support (participant perspective: interviews) | One participant was reassured that their experience was “quite a normal outcome……feelings were real and this is important [to hear]”. (Breast cancer survivor) |

| Program feedback specific to employer communications | |

| Valuable advocate for returning to work (participant perspective: interviews) | “…appreciated someone speaking ‘on my behalf and tak[ing] any awkwardness out of it’” (Breast cancer survivor) |

| Positive engagement with supportive employers (consultant perspective: focus group) | “...the employers that I dealt with were [sometimes] unsure of the process, but they were amazing…”⋯(Consultant) “Her employer was very supportive…and happy to implement any duties or any strategies that the client needed”. (Consultant) |

| Program feedback specific to exercise physiology | |

| EPs highly valued (participant perspective: interviews) | [I got referred to an] “exercise physiologist to try and get back to physical health,...but also managing that fatigue, and it was really good,…enough to help me start to get that strength back without overwhelming me…the focus is now changed…it’s [now] all about increasing bone density.” (Breast cancer survivor) |

| Barriers to participation and engagement | |

| Work pressures/commitments (survey; interviews) | “I had a lot of difficulties because I’m a manager, the expectation is you work full time or not at all”. (Breast cancer survivor) |

| Overall health and ongoing treatment (survey; interviews; consultant perspective: focus group) | “It is just so full on. It is just appointment after appointment. It’s all sorts of things happening and then trying to get through each stage of that initially.” (Breast cancer survivor) |

| Challenges to program delivery and implementation | |

| Effectiveness of consultant training—timing/delay; more scenario-based learning (consultant perspective: focus group) | “I think it’s more just the expectation of what the client’s going through……I found when they start talking about having that constant worry about it coming back, I think we didn’t (or some of us didn’t) have a lot of experience in regards to cancer.” (Consultant) |

| Timing of referral and service provision (consultant perspective: focus group; interviews) | “the program may have been better for her if she was involved right after diagnosis”; (Consultant) “I wish I had known about this earlier”; (Breast Cancer survivor) “I did have a referral that was sent too early. That individual wasn’t in the space to be able to even think about involvement with us ….” (Consultant) “any earlier, I would have still been just coping with [treatment side effects]”; (Breast cancer survivor) |

| Work Capacity | Beyond Cancer Breast Cancer Survivor Cohort (n = 55) | Historical Control Group: Cancer Survivor Cohort (n = 77) a |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Change capacity | 36 (65.5%) | 25 (32.5%) |

| No or Negative Change capacity | 19 (34.5%) | 52 (67.5%) |

| Beyond Cancer Breast Cancer Survivor Cohort (n = 44) | Historical Control Group: Cancer Survivor Cohort (n = 73) | |

|---|---|---|

| RTW pre-diagnosis hours/duties | 18 (45.00%) | 34 (46.58%) |

| RTW partial hours/duties | 20 (45.45%) | 23 (31.50%) |

| RTW New employer (Full or partial) | 1 (2.27%) | 2 (2.74%) |

| TOTAL positive RTW outcome | 39 (88.60%) | 59 (80.82%) |

| Not working at closure/receiving benefits b | 5 (11.36%) | 14 (19.18%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheppard, D.M.; O’Connor, M.; Jefford, M.; Lamb, G.; Frost, D.; Ellis, N.; Halkett, G.K.B. ‘Beyond Cancer’ Rehabilitation Program to Support Breast Cancer Survivors to Return to Health, Wellness and Work: Feasibility Study Outcomes. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 2249-2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30020174

Sheppard DM, O’Connor M, Jefford M, Lamb G, Frost D, Ellis N, Halkett GKB. ‘Beyond Cancer’ Rehabilitation Program to Support Breast Cancer Survivors to Return to Health, Wellness and Work: Feasibility Study Outcomes. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(2):2249-2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30020174

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheppard, Dianne M., Moira O’Connor, Michael Jefford, Georgina Lamb, Dorothy Frost, Niki Ellis, and Georgia K. B. Halkett. 2023. "‘Beyond Cancer’ Rehabilitation Program to Support Breast Cancer Survivors to Return to Health, Wellness and Work: Feasibility Study Outcomes" Current Oncology 30, no. 2: 2249-2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30020174

APA StyleSheppard, D. M., O’Connor, M., Jefford, M., Lamb, G., Frost, D., Ellis, N., & Halkett, G. K. B. (2023). ‘Beyond Cancer’ Rehabilitation Program to Support Breast Cancer Survivors to Return to Health, Wellness and Work: Feasibility Study Outcomes. Current Oncology, 30(2), 2249-2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30020174