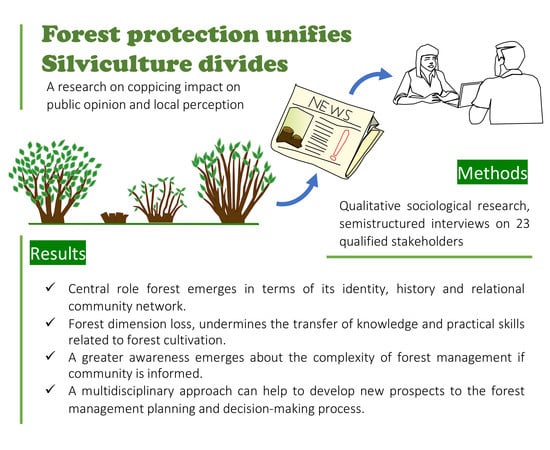

Forest Protection Unifies, Silviculture Divides: A Sociological Analysis of Local Stakeholders’ Voices after Coppicing in the Marganai Forest (Sardinia, Italy)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Context: Study Area and Forest Management from the 1850s to the Present

1.1.1. The 19th and 20th Centuries

1.1.2. The 21st Century

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

2.2. Research Sample

2.3. Interview’s Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

- Historical and identity function of the forest.

- Intergenerational cultural erosion.

- Socio-economic dimension of forestry.

- Perception of silvicultural activities.

3.1. Historical and Identity Function of the Forest

3.2. Intergenerational Cultural Erosion

3.3. Socio-Economic Dimension of Forestry

3.4. Perception of Silvicultural Activities

4. Conclusions and Final Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piussi, P.; Alberti, G. Selvicoltura Generale. Boschi, Società e Tecniche Colturali; Compagnia delle Foreste S.r.l.: Arezzo, Italy, 2015; p. 432. ISBN 978-88-98850-11-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bruna-Garcia, X.; Marey-Pèrez, M.F. Public participation: A need of forest planning. iForest 2014, 7, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sectoral Activities Department International Labour Office. Public Participation in Forestry in Europe and North America. Report of the Team of Specialists on Participation in Forestry; Joint Fao/Ece/Ilo Committee on Forest Technology, Management and Training, Geneva, CH. 2000. Available online: http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/timber/joint-committee/participation/report-participation.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- De Meo, I.; Paletto, A.; Cantiani, M.G. The attractiveness of Forests: Preferences and perceptions in a mountain community in Italy. Ann. Res. 2015, 58, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Ruda, A.; Kalasová, Z.; Paletto, A. The forest stakeholders’ perception towards the NATURA 2000 network in the Czech Republic. Forests 2020, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Giacovelli, G.; Grilli, G.; Balest, J.; De Meo, I. Stakeholders’ preferences and the assessment of forest ecosystem services: A comparative analysis in Italy. J. For. Sci. 2014, 60, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gabbrielli, A. Le vicende storiche e demografiche italiane come causa dei cambiamenti del paesaggio forestale. In ANNALI; Accademia Italiana di Scienze Forestali: Firenze, Italy, 2006; Volume 55, pp. 133–166. [Google Scholar]

- Bernetti, G.; La Marca, O. Il bosco ceduo nella realtà italiana. In Atti della; Accademia dei Georgofili: Firenze, Italy, 2012; pp. 542–585. ISBN 978-88-596-1040-3. [Google Scholar]

- Beccu, E. Tra cronaca e storia Le vicende del patrimonio boschivo in Sardegna; Carlo Delfino editore: Sassari, Italy, 2000; p. 432. ISBN 88-7138-196-3. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, M.; Vizzarri, M.; Lasserre, B.; Sallustio, L.; Tavone, A. Natural capital and bioeconomy: Challenges and opportunities for forestry. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2015, 38, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, P. Forestry research to support the transition towards a bio-based economy. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2014, 38, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbio, G. Coppice forests, or the changeable aspect of things, a review. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2016, 40, 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, G.A. La Selva Preistorica del Sulcis che Diventa Legna da Ardere. Available online: https://www.corriere.it/scienze/15_settembre_07/selva-preistorica-sulcis-che-diventa-legna-ardere-1c366754-5524-11e5-b550-2d0dfde7eae0.shtml (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- O’Brien, E.A. Human values and their importance to the development of forestry policy in britain: A literature review. Forests 2003, 76, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farcy, C.; Devillez, F. New orientations of forest management planning from an historical perspective of the relations between man and nature. For. Pol. Econ. 2005, 7, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelhas, J.; Zabawa, R.; Molnar, J.J. New opportunities for social research on forest landowners in the South. South. Rur. Sociol. 2003, 19, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, R.L.; Canavera, E. Domusnovas Dalle Origini al ′900: Ricerca Storica, Documentaria, Bibliografica e sul Territorio; Comune di Domusnovas: Domusnovas, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Airi, M.; Casula, A.; Asoni, G. Piano Di Gestione Complesso Marganai-Ripristino Del Governo a Ceduo Su Aree Demaniali; Personal Communication: Cagliari, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- SardegnaForeste Notizie. Available online: https://www.sardegnaforeste.it/notizia/avvio-della-pianificazione-forestale-particolareggiata-nelle-foreste-demaniali (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Niccolini, M.; Perrino, M. Piano Forestale Particolareggiato Del Complesso Forestale “Marganai” Ugb “Marganai”-“Gutturu Pala” Relazione Tecnica. Available online: http://www.sardegnaambiente.it/documenti/3_68_20140701114331.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- A.T.P “C.C.W.R” progettazioni e soluzioni ambientali, sviluppo equo ed ecosostenibile. Richiesta incontro tecnico: discussione su problematiche riscontrate su habitat forestali in area SIC MONTE LINAS-MARGANAI ITB041111 e limitrofe, 2015. Letter addressed to the “Sardegna Regional Forest Service”, dated 11 Novembre 2014. Available online: https://gruppodinterventogiuridicoweb.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/richiesta-incontro-tecnico-ente-for.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Gruppo d’Intervento Giuridico odv. Foreste demaniali sarde e direttiva Habitat, un contributo del dott. Francesco Aru. Available online: https://gruppodinterventogiuridicoweb.com/2014/06/20/foreste-demaniali-sarde-e-direttiva-habitat-un-contributo-del-dott-francesco-aru/ (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Giadrossich, F.; Guastini, E. A critical analysis of Vacca, A., Aru, F., Ollesch, G. (2017). Short term impact of coppice management on soil in a Quercus ilex L. Stand in Sardinia. Land Degradation & Development 2019, 28, 553–565. Land Degrad. Develop. 2019, 30, 1765–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piano Di Gestione Dei Tagli Boschivi Del Cf N °-15- Marganai– Ugb 1, Allegato A, Capitolato Tecnico Delle Condizioni Sotto le Quali è Posto in Vendita il Materiale Legnoso Proveniente dal Ceduo Semplice con Rilascio di Matricine del Bosco Sito in Località “Su Caraviu E Su Isteri” in Agro del Comune Di Domusnovas. Regione Autonoma della Sardegna, Ente Foreste della Sardegna. 2010. Available online: http://www.sardegnaambiente.it/documenti/3_233_20100204102403.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 8th ed.; Pearson/Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman, I. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences, 3rd ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, H. The logic of qualitative survey research and its position in the field of social research methods. Forum Qualit. Soci. Res. 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, G. Tell me about…: Using interviews as a research methodology. In Methods in Human Geography: A Guide for Students Doing a Research Project, 2nd ed.; Flowerdew, R., Martin, D., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Essex, UK, 2005; pp. 110–126, ISBN-13: 9780582473218. [Google Scholar]

- Vargiu, A. Metodologia e Tecniche per la Ricerca Sociale, 1st ed.; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2007; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, A.L.; Miles, S. Stakeholders: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 362. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.R.; Qureshi, M.E. Choice of stakeholder groups and members in multi-criteria decision models. Nat. Resour. For. 2000, 24, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantakos, P. Social Research, 4th ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 536. [Google Scholar]

- Ananda, J.; Herath, G. The use of analytic hierarchy process to incorporate stakeholder preferences into regional forest planning. For. Pol. Econ. 2003, 5, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candrea, A.N.; Bouriaud, L.A. Stakeholders’ analysis of potential sustainable tourism development strategies in Piatra Craiului National Park. Ann. For. Res. 2009, 52, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schram, T.H. Conceptualizing and Proposing Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN-13: 978-0131702868. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Archer, M.S. Making Our Way Through the World: Human Reflexivity and Social Mobility; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; ISBN-13: 978-0521696937; ISBN -13. [Google Scholar]

- Fukujama, F. Social Capital, Civil society and development. Third World Quart 2001, 22, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A. Community resilience, globalization, and transitional pathways of decision making. Geoforum 2012, 43, 1218–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftslehre; TP Verone Publishing: Einbeck, Germany, 2013; p. 588. ISBN 9783863831936. [Google Scholar]

- Goudy, W.J. Community attachment in a rural region. Rur. Soc. 1990, 55, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannerz, U. Transnational Connections. Culture, People, Places, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. 216. ISBN 9780415143097. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; p. 480, ISBN-13: 978-0465097197. [Google Scholar]

- Griswold, W. Cultures and Society in a Changing World, 2nd ed.; Pine Forge Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, M. Towards a rural sociological imagination: Ethnography and schooling in mobile modernity. Ethnol. Educ. 2015, 10, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieder, T.; Garkovich, L. Landscapes: The social construction of nature and the environment. Rural Sociol. 1994, 59, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, M. The Tacit Dimension; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; p. 128, ISBN-13: 978-0226672984. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. La distinction. Critique sociale du jugement; Minuit: Paris, France, 1979; p. 670, ISBN-13: 978-2707302755. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Raisons Pratiques. Sur la Théorie de L’action; Seuil: Paris, France, 1994; p. 252, ISBN-13: 978-2020231053. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. Assets and affect in the study of social capital in rural communities. Sociol. Rur. 2016, 56, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burke, P. Sociology and History; Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1980; p. 116, ISBN-13: 9780043011157. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, L. Urbanism as a Way of Life; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1964; pp. 60–83. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N. Implosion/Explosion: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2014; p. 573, ISBN-13: 978-3868593174. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Dynamics. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/ (accessed on 27 January 2019).

- Bell, M. The fruit of difference: The rural-urban continuum as system of identity. Rural Sociol. 1992, 57, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.J. The Urbanism of Exception. The Dynamics of Global City Building in the Twenty-First Century; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; p. 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongratz, H. Cultural tradition and social change in agriculture. Sociol. Rur. 1990, 30, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mardsen, T.; Lowe, P.; Whatmore, S. Rural Reconstructuring. Global Processes and Their Responses; Fulton Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 1990; p. 197. ISBN 1853461113. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; p. 200, ISBN-13: 978-0745609232. [Google Scholar]

- De Meo, I.; Ferretti, F.; Paletto, A.; Cantiani, M.G. An approach to public involvement in forest landscape planning in Italy: A case study and its evaluation. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2017, 41, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touraine, A. Pourrons-Nous Vivre Ensemble? Fayard: Paris, France, 1997; p. 395, ISBN-10: 221359872X. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; D’Arge, R.; De Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruel, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, S.C.; Costanza, R.; Wilson, M.A. Economic and ecological concepts for valuing ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Comín, F.A.; Escalera-Reyes, J. A framework for the social valuation of ecosystem services. Ambio 2015, 44, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matthews, J.D. Silvicultural Systems; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1991; p. 296, ISBN-13: 978-0198546702. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, G.P. Ecology and Management of Coppice Woodlands; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1992; p. 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneifl, M.; Kadavy, J.; Knott, R. Gross value yield potential of coppice, high forest and model conversion of high forest to coppice on best sites. J For. Sci. 2011, 57, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, J.J. Conceiving forest management as providing for current and future social value. For. Ecol. Man. 1985, 13, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmithüsen, F. Multifunctional forestry practices as a land use strategy to meet increasing private and public demands in modern societies. J. For. Sci. 2007, 53, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, J.; Hill, C.A.; Dean, E. Social Media, Sociality and Survey Research; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Public opinion does not exist. In Communication and Class Struggle; Mattelart, A., Siegelaub, S., Eds.; International General: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 124–130. ISBN 0-88477-011-7. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit. Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft; Suhrkamp Verlag AG: Frankfurt, Germany, 2001; p. 391, ISBN-13: 978-3518284919. [Google Scholar]

- Nikodinoska, N.; Paletto, A.; Pastorella, F.; Granvik, M.; Franzese, P.P. Assessing, valuing and mapping ecosystem services at city level: The case of Uppsala (Sweden). Ecol. Model. 2018, 368, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, D.A.; Stokes, M.K. Public participation and institutional fit: A social-psychological perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Folke, C.; Pritchard, L.; Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Svedin, U. The problem of fit between ecosystems and institutions: Ten years later. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tirivayia, N.; Nennena, L.; Tesfayea, W.; Mab, Q. The benefits of collective action: Exploring the role of forest producer organizations in social protection. For. Pol. Econ. 2018, 90, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegner, M.; Hagerman, S.; Kozak, R. Going deeper with documents: A systematic review of the application of extant texts in social research on forests. For. Pol. Econ. 2018, 92, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augé, M. Non-lieux. Introduction à Une Anthropologie de la Surmodernité; Seuil: Paris, France, 1992; p. 150, ISBN-13: 978-2020125260. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; p. 228. ISBN 0-7456-2409-X. [Google Scholar]

- Zoppi, C.; Lai, S. Assessment of the regional landscape plan of Sardinia (Italy): A participatory-action-research case study type. Land Use Pol. 2010, 27, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijnik, A.; Nijnik, M.; Kopiy, S.; Zahvoyska, L.; Sarkki, S.; Kopiy, L.; Miller, D. Identifying and understanding attitudinal diversity on multi-functional changes in woodlands of the Ukrainian Carpathians. Clim. Res. 2017, 73, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soe, K.T.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Perceptions of forest-dependent communities toward participation in forest conservation: A case study in Bago Yoma, South-Central Myanmar. For. Pol. Econ. 2019, 100, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campus, S.; Scotti, R.; Piredda, I.; Murgia, I.; Ganga, A.; Giadrossich, F. The open data kit suite, a mobile data collection technology as an opportunity for forest mensuration practices. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2020, 44, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichi, R. La Conduzione Delle Interviste Nella Ricerca Sociale, 2nd ed.; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2011; p. 216. ISBN 9788843038008. [Google Scholar]

- Galletta, A. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 258. ISBN 9780814732939. [Google Scholar]

| Macro Dimension of the Interview | Main Tracks |

|---|---|

| History and traditional uses | What does the forest of Marganai mean in your life and in that of your community? |

| How has the way of living the Marganai Forest changed in the local community? | |

| What is the territory that Marganai Forest refers to? (please sketch on the “silent map” that is on the table, your memory of the boundaries of the forest) | |

| How has the way of living the Marganai forest changed from a political/administrative point of view? (administrators only) | |

| Perception of resources | How does the forest relate to the economic, political and social dynamics of the territory? |

| In your opinion, what are the needs of the territory of reference? | |

| Are the material resources of the Marganai Forest an economic and work source for its territory? | |

| How can the Marganai Forest be valued from an economic point of view? | |

| What is your knowledge and opinion about the production and consumption of firewood in the territory? | |

| Knowledge of coppice management | What information do you have about what happened as a result of the use of the Marganai’s forest resources? |

| What were your sources of information on this matter? | |

| What is your opinion about the use of the Marganai’s forest resources? | |

| In your opinion, what is the relationship between the depopulation process and the possible dynamics of economic development? | |

| What relations do you have with the companies that have operated within the Marganai forest? | |

| Future | How do you see the Marganai Forest in 10 years? |

| Do you think you can do forestry in Sardinia? (administrators only) | |

| What business prospects do you see in the near future? | |

| Would you like to add something we haven’t asked you? |

| Witnesses | n |

|---|---|

| Public administration at different levels and organization | 7 |

| Companies in agroforestry, firewood, and timber sales | 8 |

| Naturalistic associations, hiking associations, museums, others social and cultural actors, and journalists | 8 |

| Total number of interviews | 23 |

| H.I. | I.C. | Witness’s Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Collective identity | W-03 | “It is an identity factor. Identity […] concerns the sense of recognition of places, that is, the recognition of home, and the sense of landscape, both physical and human.” |

| W-13 | “The Marganai is part of my personal history. As a child, I used the Marganai forest. […] Marganai forest plays an educational role for us.” | |

| W-14 | “We felt the Marganai as something that belonged to the community.” | |

| W-17 | “The presence, even visual, of a massif of this type [Marganai’s mountains] has influenced the modus vivendi of all the inhabitants of the territory.” | |

| Forest as a social actor | W-02 | “From an historical-cultural point of view, it is an area that represents a point of recognition of the identity of the territory: local people have a point of reference to read their own story because the Marganai has always linked the relationships between local populations and the resources it has offered.” |

| W-11 | “What does it represent for the inhabitants of Iglesias? Surely a green lung used over the years to make trips, to go hiking and to disconnect from the urban context.” | |

| W-13 | “I think every inhabitant of Iglesias has a piece of his history linked to the Marganai forest.” | |

| Resources of the forest system | W-09 | “Long ago, people did not create too much trouble with their use of wood. Maybe they did so with intelligence because these are forests that have endured over the centuries. Evidently, there was a certain ability to work the forest, especially compared to today. […] Perhaps the old men were ahead of many young people.” |

| W-14 | “The territory lived in symbiosis with the needs of the urban world.” | |

| W-19 | “The woods are anthropized places that live in a symbiotic way with the man who exploits them and that makes them grow in a decent way and does not destroy them.” |

| H.I. | I.C. | Witness’s Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Abandoned rural areas | W-01 | “People are no longer used to non-urban outdoor life. Everyone goes to the sea but the Marganai forest is little known.” |

| W-02 | “The voices being heard are the ones that are not from those places…it’s the public opinion of city-dwellers, people who live far away from those places. […] What emerges, however, is a public opinion disconnected from the specific context.” | |

| W-05 | “[The local population] was split in two: those who know the territory, and saw similar works, were happy; others, who have never been in Marganai but who have seen it written on Facebook, have sided against it. The town was split in two.” | |

| W-15 | “Unlike the inhabitants of Domusnovas and Fluminimaggiore, the inhabitants of Iglesias are more detached from the mountain. […] There are people who know other areas of Sardinia better, [areas that are] more publicized, but who do not know what we have near here.” | |

| Environmentalist | W-02 | “What is happening is a lack of rural culture, and forestry in particular […] that made it possible to understand certain dynamics of the forest, agriculture, breeding… To understand these dynamics in depth and then to understand and support the balance between needs of local populations and system sustainability.” |

| W-15 | “We are losing this culture, it is fading. We should combine it with the natural heritage.” | |

| W-19 | “I fear that the municipal administrations are sons of this abandonment of the forest. It is a historical question: if I were the Mayor, and I knew nothing about the forest, I would not even know how to exploit it in a positive way.” | |

| Urban-centric perspective | W-03 | “The rural areas are today seen as “a some-place” that is at the disposal of the city” |

| W-13 | “I have an opinion that sometimes clashes with the opinion of “Taliban naturalists”. I live the forest, I agree not to rape it, but the forest must be usable for everyone. You must give everyone the opportunity to use it.” | |

| W-19 | “Everything is the result of ignorance. To relate to the forest as a tropical forest where there are natives who have never seen a human being… This is the product of a very radical-chic attitude. The new generation of environmentalists knows nothing about the forest and approaches the forest of Marganai thinking that it is the Amazon.” | |

| W-22 | “A certain type of environmentalism, which I call “environmental Talibanism”, has conditioned political choices.” | |

| Loss of cultural capital | W-06 | “Because people are used to seeing deforestation in the Amazon forest. Because people now know everything about an African elephant or a Bengali tiger, but they do not know a partridge, they do not know what a hare is. This is the drama of Sardinians.” |

| W-09 | “The environmental aspect... the fact that a forest is destroyed has been held up as a scandal. […] There was a contrast between foresters, the municipal administration of Domusnovas and environmentalists, who do not look favorably upon use of the forest.” | |

| W-10 | “The environmentalist or the animalist is always listened to. I say to be cautious because they are not always right. But we must try to find common ground.” |

| H.I. | I.C. | Witness’s Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Resilience of the forest | W-04 | “Before, the forest tended to be better than now. Now the cuts have been abandoned. One goes there and can almost not pass through. You only find holm oaks. […] The forest must not die but we must try to make it rejuvenate over time. It must always be alive.” |

| W-05 | “Before, when the forest was inhabited, it created income. It was lived in and gave lots of wood to the population. This too was “inhabiting the territory”. Being present also means preserving.” | |

| W-06 | “If you leave a forest alone, over the decades you will have nothing but a holm oak forest […] you will not find anything underneath, not even a blade of grass. If you periodically exploit the forest you have an economic yield from the wood that you collect, and, what’s more, you’re rejuvenating the forest.” | |

| Attitudes for and against the cuts | W-14 | “Why does silviculture frighten us? It has always been there since the dawn of time, whereas before logs were used to roll the rocks to build the pyramids, today they are used to make firewood and for other uses. […] The moment we limit its use, we no longer have any connection with the habitat of human beings.” |

| W-19 | “I have seen other woods in Italy […] that an ignorant person like me could judge as a primitive forest, but in reality, is the result of a “cultivation”. “Millennial cultivation” by the monks who transformed it into that wonder that is now. So, I’ve got a slightly different idea of what a forest must be like.” | |

| W-11 | “My idea is that the forest is like the home garden and must be taken care of. We do not have to be radicals but if we want to use the forest, we have to make it usable. The holm oak forests must be pruned and put in condition to grow more and live well. It must be cleaned and the undergrowth must be made accessible. Otherwise, it starts to deteriorate.” |

| H.I. | I.C. | Witness’s Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Violence against the forest | W-01 | “Even those who have studied silviculture for forty years tell us that the ‘problem of cutting trees’ in recent years is worsening because there is less and less historical memory of country life.” |

| W-02 | “There are difficulties in the management of the forest because people who work in it, and are therefore aware of that cultural heritage that allowed us to understand the balance between natural resources and local populations, are few and isolated. They are struggling and increasingly relegated [ignored] and do not have time to give strength to their voice in the matter” | |

| W-14 | “[Before] the territory lived in symbiosis with the needs of the urban world. [Now] the metropolitan citizen, who has all his comforts, […] wants all forests to be virgin forests.” | |

| Public opinion | W-01 | “Public opinion associates the cutting of the forest to the desert of Africa. So, cuts are equal to desertification and desert. […] The cutting of the forest is a cyclic phase; it is a cultivation cut that is used to rejuvenate a forest that is not a natural forest.” |

| W-05 | “[Public opinion] was divided into two. Those who know the area and have seen similar jobs were more than happy. Others, who have never seen anything on the spot but who have seen it written on Facebook, have lined up against. The country split into two.” | |

| W-15 | “What the public opinion knows is that this cutting has been done in an inconsiderate way… And surely it came out that they were destroying the forest.” | |

| Communication flows | W-09 | “We read it especially on a site that launched this thing. […] In fact, I do not know how the situation is. However, there was a conflict between foresters and the municipal administration of Domusnovas, and environmentalists who, as said the commissioner, do not look favorably at the use of wood.” |

| W-13 | “There was a debate on Facebook and in the newspapers. They said: “They cut half of the Marganai forest”. But it is only a part, it is certainly not half a forest. Unfortunately, with social media things are swollen to excess.” | |

| W-14 | “Social networks have combined damage with news sharing. Many people who shared that news were people who do not know the forest. Maybe even locals who you see in the square 24 h on 24 but who have never set foot on the Marganai […]. But they were ready to sentence on the cuts.” | |

| W-19 | “What I know is that I have read online newspapers. I informed myself and that made me lean towards this position: “There is someone who has economic interests to destroy the forest”. This is the image given by the newspapers.” | |

| Reliability and scientific validity | W-13 | “Information is what is missing from the institutions. What’s on the internet is not information, it’s something else. The information is the official one of those who have decided these things: Mayor, Regional Administrator, and all the interested people. They should have said, “This is what is going to happen in Marganai”. And I think that people who have skills and who know the mountains could also have agreed with this information.” |

| W-15 | “At times alarmism is caused by not knowing what is happening. Surely, there is a lack of information.” | |

| W-16 | “The cuts have not been explained to the population. What has triggered the uprising is that this cut has not been explained. […] From my point of view, information has not passed on or, if it has been given, it has not been enough. […] I am convinced that if they had given more complete information, many would have been less opposed. If they gave guarantees there would be fewer problems.” | |

| W-19 | “If the municipal administrations had thought of involving stakeholders, perhaps involving them in some collective assembly and explaining the development plans, maybe we would not have arrived at this point.” |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Branca, G.; Piredda, I.; Scotti, R.; Chessa, L.; Murgia, I.; Ganga, A.; Campus, S.F.; Lovreglio, R.; Guastini, E.; Schwarz, M.; et al. Forest Protection Unifies, Silviculture Divides: A Sociological Analysis of Local Stakeholders’ Voices after Coppicing in the Marganai Forest (Sardinia, Italy). Forests 2020, 11, 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11060708

Branca G, Piredda I, Scotti R, Chessa L, Murgia I, Ganga A, Campus SF, Lovreglio R, Guastini E, Schwarz M, et al. Forest Protection Unifies, Silviculture Divides: A Sociological Analysis of Local Stakeholders’ Voices after Coppicing in the Marganai Forest (Sardinia, Italy). Forests. 2020; 11(6):708. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11060708

Chicago/Turabian StyleBranca, Giampiero, Irene Piredda, Roberto Scotti, Laura Chessa, Ilenia Murgia, Antonio Ganga, Sergio Francesco Campus, Raffaella Lovreglio, Enrico Guastini, Massimiliano Schwarz, and et al. 2020. "Forest Protection Unifies, Silviculture Divides: A Sociological Analysis of Local Stakeholders’ Voices after Coppicing in the Marganai Forest (Sardinia, Italy)" Forests 11, no. 6: 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11060708

APA StyleBranca, G., Piredda, I., Scotti, R., Chessa, L., Murgia, I., Ganga, A., Campus, S. F., Lovreglio, R., Guastini, E., Schwarz, M., & Giadrossich, F. (2020). Forest Protection Unifies, Silviculture Divides: A Sociological Analysis of Local Stakeholders’ Voices after Coppicing in the Marganai Forest (Sardinia, Italy). Forests, 11(6), 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11060708