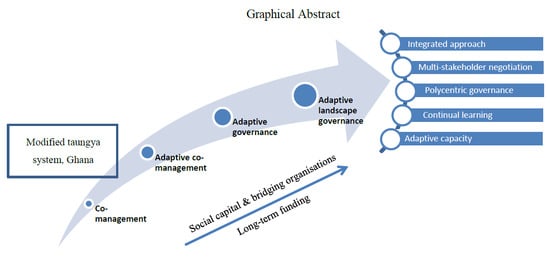

From Co-Management to Landscape Governance: Whither Ghana’s Modified Taungya System?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Principles of Adaptive Landscape Governance

2.1.1. Integrated Approach

2.1.2. Multi-Stakeholder Negotiation

| Characteristic | Co-Management | Adaptive Co-Management | Adaptive Governance | Landscape Governance [15] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Oriented towards community-level resource users [12] | Tailored to specific places (community level) [3] | Involving multiple scales [4,6] | Landscape scale, involving multiple scales |

| Scope | Oriented towards sustainable management of common pool resources (forests, fisheries) [12]. Focused on sustainable provision of products and ecosystem services [12] | Largely resource-oriented, but situating resource use in social ecological systems (SES) [4,5]. Oriented towards problem solving [12] | Integrated approach focusing on social ecological systems (SES) [4]. Oriented towards building adaptive capacity and resilience to cope with change, disturbances and uncertainty [4,6,7] | Integrated approach focusing on multifunctional landscapes that provide multiple values, products and services. Oriented towards increasing resilience and maintaining landscape attributes that provide resilience to undesirable changes |

| Actor constellations | Power and responsibilities shared between government agencies and local resource users [12] | Power and responsibilities shared between government agencies and local resource users [12]. Supported by organisations from multiple scales [1]. Flexible institutional arrangements & networks [4,10] | Collaboration between public and private actors operating at multiple scales [4,7,10]. Polycentric governance arrangements based on organisational and institutional flexibility [45,46]. Social capital (trust, reciprocity, common rules, norms and sanctions, and connectedness in networks and groups) as a basis for self-organisation [1,10,23,24]. Rules and enforcement [47] | Multiple stakeholders equitably engaged in decision-making, requiring conflict management, trust, dealing with power differences, and transaction costs. Negotiated and shared goals and transparent change logic. Clarification of rights and responsibilities, including rules of resource access and land use, a fair justice system for conflict resolution and recourse, and negotiation of conflicting claims |

| Role of learning | Simple exchange of information [12]; tendency to distrust local and tacit knowledge [1] | Based on self-organised learning-by-doing [3,9] | Ongoing learning to live with uncertainty and change by combining multiple types of knowledge [5]. Self-organisation to monitor and respond to environmental feedbacks based on social learning and trustworthy information flows [23,48] | Continual learning and adaptive management. Strengthened stakeholder capacity for effective participation. Participatory and user-friendly monitoring based on shared learning and information |

| Role of bridging organisations | Minimal or no role | Important role for bridging organisations to mobilise resources, knowledge and other incentives; knowledge brokering) [1] | Bridging organisations facilitate cross-scale interactions [4,49]. Leadership to build trust, mobilise support and knowledge, and manage conflicts [4,6] | Bridging organisations do not receive a lot of attention in the literature but play an important role in practice |

| Principle | Dimensions | Specification/Example | Equivalent Principles of Landscape Governance [15] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated approach | Integration of social and ecological aspects [4] | Landscapes as social-ecological systems–acknowledging social and ecological dynamics [43] | Principle 9: Resilience |

| Integration of conservation and development aims [15] | Targeting food security, environmental services (e.g., carbon sequestration, biodiversity), and commodity production (e.g., timber) [35,42,43] | Principle 4: Multifunctionality | |

| Multi-stakeholder negotiation | Negotiation of goals [15] | Goals in terms of land-use (change), production targets [15] | Principle 2: Common concern entry point (shared values and objectives) |

| Shared vision and negotiated change logic [15] | Consensus on objectives, challenges, options, opportunities, based on awareness of risks and free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) [15] | Principle 6: Negotiated and transparent change logic | |

| Negotiation of trade-offs [15] | Which trade-offs between conservation and development or different productive land uses do stakeholders consider as acceptable? [15] | Principles 2 and 6 | |

| Polycentric governance | Hybridity [45] | Mixed types of institutional arrangements, building on existing and new ones e.g., traditional authorities, stools, CBAGs (community-based advisory groups), forest forums | Principle 5: Multiple stakeholders. Principle 3: Multiple scales |

| Clear rights, responsibilities, benefits [45] | Land-use rights, harvesting rights, responsibilities regarding tree planting and maintenance, benefit-sharing arrangements | Principle 7: Clarification of rights and responsibilities | |

| Legal options for self-organisation [45] | Taungya committees and associations | Principle 5 Principle 10: Strengthened stakeholder capacity | |

| Continual learning | Single loop-learning: improving routines [7,22] | Adapt day-to-day management practices, (e.g., greater spacing between seedlings) or creating bylaws to refine existing regulations | Principle 1: Continual learning and adaptive management |

| Double loop-learning: reframing assumptions [7,22] | Adapt assumptions about problems, goals and how best to achieve them, e.g., allowing experimentation with cassava planting | Principle 8: Participatory and user-friendly monitoring | |

| Triple loop-learning: transforming underlying norms and values [7,22] | Transformation of the structural context, e.g., a shift from reforestation to a landscape approach | Principles 6 and 10 | |

| Institutional memory [50] | Learn from monitoring and evaluation | Principle 8 | |

| Adaptive capacity | Being prepared for change [47] | Flexibility to adapt alternative solutions (e.g., regarding cassava planting) | Principles 1, 2, 6, 8, 9 |

| Willingness to engage in collective decision making and share power [51,52] | Taungya associations with autonomy to design and implement bylaws | Principles 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 | |

| Accept a diversity of solutions, actors and institutions [50,51,52] | Accept different ways of solving a problem [50] | Principles 2, 4, 5, 6 | |

| Room for autonomous change [50] | Enhancing actor capacity to self-organize and innovate; foster social capital [50] | Principles 1 and 9 |

| Enabling Condition | Dimensions | Specification/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Social capital [55,56,57] |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| ||

| Bridging organisations [1,3,4,20,23,58] |

|

|

|

| |

| Long-term funding [23] |

|

|

|

2.1.3. Polycentric Governance

2.1.4. Continual Learning

2.1.5. Adaptive Capacity as Preparedness for Change

2.2. Enabling Conditions

2.2.1. Social Capital

2.2.2. Bridging Organisations

2.2.3. Long-Term Funding

2.3. Data Sources

3. Results: the MTS and Criteria for Adaptive Landscape Governance

3.1. Principle 1: Integrated Approach

3.2. Principle 2: Multi-Stakeholder Negotiation

3.3. Principle 3: Polycentric Governance

| Key Stakeholder | Interest | Responsibility | Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forestry Commission (FC) | Need to restore degraded forest reserves and address timber deficit; implementing the Forest Development Master Plan | Demarcation of degraded forest reserves; supplying the MTS farmers with pegs and seedlings; providing training and extension services; marketing and accounting of the plantation products; financial management and supervision; fire prevention and control | A 40% share in the timber revenues; restoration of degraded forest reserves; tree ownership |

| MTS farmers | Land to grow food crops; livelihood improvement; co-ownership of trees; share in timber revenues | Provision of labour for site clearing, pegging, tree planting and maintenance, and wildfire protection; fire prevention and control | Revenues from food crops; a 40% share in timber revenues; co-ownership of trees with the FC |

| Stool landowner and traditional authority | Investment in forest land; royalties | Provision of land within the degraded forest reserve; guaranteeing uninterrupted access to the allocated land | A 15% share in the timber revenues; land ownership |

| Local community | Availability of natural resources and farming land; share in timber revenue as SRA * | Assisting the FC to prevent and control fire outbreaks and illegal activities within the plantation | A 5% share in timber revenues as SRA * |

| Timber companies | Secure supplies of timber | Payment of an export levy on unprocessed air-dried timber as one of the funding sources of the scheme | Option to buy timber at the prevailing market price |

3.4. Principle 4: Continual Learning

3.5. Principle 5: Adaptive Capacity as Overall Willingness to Change

3.6. Enabling Condition 1: Social Capital

3.7. Enabling Condition 2: Bridging Organisations

3.8. Enabling Condition 3: Long-Term Funding

4. Discussion: From Co-Management to Adaptive Landscape Governance

4.1. Lessons Learned from the CFMP

4.2. Challenges Ahead

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berkes, F. Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 5, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Rethinking community-based conservation. Cons. Biol. 2004, 13, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Hahn, T. Social-ecological transformation for ecosystem management: The development of adaptive co-management of a wetland landscape in southern Sweden. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 4. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss4/art2/ (accessed on 4 July 2014).

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.R.; Plummer, R.; Berkes, F.; Arthur, R.I.; Charles, A.T.; Davidson-Hunt, I.J.; Diduck, A.P.; Doubleday, N.C.; Johnson, D.S.; Marschke, M.; et al. Adaptive co-management for social-ecological complexity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 2, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Gunderson, L.H.; Carpenter, S.R.; Ryan, P.; Lebel, L.; Folke, C.; Holling, C.S. Shooting the rapids: Navigating transitions to adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art18/ (accessed on 4 July 2014).

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 3, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Armitage, D.R.; deLoë, R.C. Adaptive comanagement and its relationship to environmental governance. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 1. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-05383-180121 (accessed on 4 July 2014).

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G. Co-Management of Natural Resources: Organising, Negotiating and Learning by Doing; IUCN: Yaoundé, Cameroon, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, R.; FitzGibbon, J. Connecting adaptive co-management, social learning, and social capital through theory and practice. In Adaptive Co-Management: Collaboration, Learning and Multi-Level Governance; Armitage, D., Berkes, F., Doubleday, N., Eds.; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2007; pp. 38–61. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Hare, M. Processes of social learning in integrated resources management. J. Community Appl. Soc. 2004, 14, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, L.; Berkes, F. Co-management: Concepts and methodological implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 1, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.; Marschke, M.; Plummer, R. Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007, 1, 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Görg, C. Landscape governance: The politics of scale and the natural conditions of places. Geoforum 2007, 38, 954–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, J.; Sunderland, T.; Ghasoulc, J.; Pfund, J.L.; Sheilb, D.; Meijaard, E.; Ventera, M.; Boedhihartonoa, A.K.; Day, M.; Garcia, C.; et al. Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land-uses. PNAS 2013, 110, 8349–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Oosten, C.; Gunarso, P.; Koesoetjahjo, I.; Wiersum, F. Governing forest landscape restoration: Cases from Indonesia. Forests 2014, 6, 1143–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, W.; Wertz, B. Global Landscape Forum Bulletin. A summary report of the Global Landscapes Forum. IISD Reporting Services 2013, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren, P. Negotiating the landscape approach. DG’s blog. Thoughts from CIFOR’s Director General. Available online: http://blog.cifor.org/25043/negotiating-the-landscape-approach-holmgren#.VGArR_mG-So (accessed on 10 November 2014).

- Kooiman, J.; Bavinck, M. Theorizing governability—The Interactive Governance Perspective. In Governability of Fisheries and Aquaculture: Theory and Applications; MARE Publications Series No. 7; Bavinck, M., Chuenpagdee, R., Jentoft, S., Kooiman, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Leys, A.J.; Vanclay, J.K. Social learning: A knowledge and capacity building approach for adaptive co-management of contested landscapes. Land Use Policy 2011, 3, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, R.S.; Cinner, J.E.; Nielsen, J.R.; Andrew, N.L. Conditions for successful co-management: Lessons learned in Asia, Africa, the Pacific, and the wider Caribbean. In Small- Scale Fisheries Management: Frameworks and Approaches for the Developing World; Pomeroy, R.S., Andrew, N., Eds.; Centre for Agricultural Bioscience International: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, D.; Marschke, M.; Plummer, R. Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundill, G.; Fabricius, C. Monitoring the governance dimension of natural resource co-management. Ecol. Soc. 2010. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss1/art15/ (accessed on 4 July 2014).

- Schröter, B.; Sessin-Dilascio, K.; Meyer, C.; Matzdorf, B.; Sattler, C.; Meyer, A.; Giersch, G.; Jericó-Daminello, C.; Wortmann, L. Multi-level governance through adaptive co-management: Conflict resolution in a Brazilian state park. Ecol. Proc. 2014, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, V.K. Promoting smallholder plantations in Ghana. Plantations and forest livelihoods. Arborvitae 2006, 31, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kalame, F.B.; Aidoo, R.; Nkem, J.; Ajayie, O.C.; Kanninen, M.; Luukkanen, O.; Idinoba, M. Modified taungya system in Ghana: A win-win practice for forestry and adaptation to climate change? Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkyi, M.A.A. Fighting over Forest. In Interactive Governance of Conflicts over Forest and Tree Resources in Ghana’s High Forest Zone; African Studies Centre: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Insaidoo, T.F.G.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.F.; Hoogenbosch, L.; Acheampong, E. Addressing forest degradation and timber deficits: Reforestation programmes in Ghana. ETFRN News. 2012, 53, 230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Insaidoo, T.F.G. Forest Governance Arrangements and Innovations for Improving the Contribution of Ghana’s Reforestation Schemes to Local Livelihoods. Ph.D. Thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ros-Tonen, M.A.F.; Insaidoo, T.F.G.; Acheampong, E. Promising start, bleak outlook: The Role of Ghana’s Modified Taungya System as a Social Safeguard in Timber Legality Processes. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 32, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasanga, K. Current land policy issues in Ghana. In Land Reform; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2003; pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fumey Nassah, V.; Resource Management Support Centre, Kumasi, Ashanti Region, Ghana. Personal communication, 2014.

- Scherr, S.; Shames, S.; Friedman, R. From climate-smart agriculture to climate-smart landscapes. Agric. Food Sec. 2012, 1. Available online: http://www.agricultureandfoodsecurity.com/content/pdf/2048-7010-1-12.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2014).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Climate-Smart Agriculture Sourcebook; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tscharntke, T.; Clough, Y.; Wanger, T.C.; Jackson, L.; Motzke, I.; Perfecto, I.; Vandermeer, J.; Whitbread, A. Global food security, biodiversity conservation and the future of agricultural intensification. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 151, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insaidoo, T.F.G.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.F.; Acheampong, E. On-farm tree planting in Ghana’s high forest zone: The need to consider carbon payments. In Governing the Provision of Ecosystem Services; Muradian, R., Rival, L., Eds.; Springer Publishers: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 437–463. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, G. The Ecosystem Approach: Learning from Experience; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pfund, J.L. Landscape-scale research for conservation and development in the tropics: Fighting persisting challenges. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2010, 1, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colfer, C.J.P.; Pfund, J.-P.; Sunderland, T. The essential task of “muddling through” to better landscape governance. In Collaborative Governance of Tropical Landscapes; Colfer, C.J.P., Pfund, J.-P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Ros-Tonen, M.A.F.; van Leynseele, Y.P.B.; Laven, A.; Sunderland, T. Landscapes of social inclusion: Reassessing inclusive development through the lenses of food sovereignty and landscape governance. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2014. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social—Ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 2. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/art5 (accessed on 4 July 2014).

- O’Farrell, P.J.; Anderson, P.M. Sustainable multifunctional landscapes: A review to implementation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2010, 1, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalan, B.; Onial, M.; Balmford, A.; Green, R.E. Reconciling food production and biodiversity conservation: Land sharing and land sparing compared. Science 2011, 333, 1289–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusters, K.; Lammers, E. Rich Forests—The Future of Forested Landscapes and Their Communities; Rich Forests Initiative, Both ENDS: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nagendra, H.; Ostrom, E. Polycentric governance of multifunctional forested landscapes. Int. J. Commons. 2012, 2, 104–133. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The struggle to govern the commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkes, F. Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 5, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, D.W.; Adger, W.N.; Berkes, F.; Garden, P.; Lebel, L.; Olsson, P.; Young, O. Scale and cross-scale dynamics: Governance and information in a multilevel world. Ecol. Soci. 2006, 2. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss2/art8/ (accessed on 4 July 2014).

- Gupta, J.; Termeer, C.; Klostermann, J.; Meijerink, S.; van den Brink, M.; Jong, P.; Nooteboom, S.; Bergsma, E. The adaptive capacity wheel: A method to assess the inherent characteristics of institutions to enable the adaptive capacity of society. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D. Adaptive capacity and community-based natural resource management. Environ. Manag. 2005, 6, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navigating Social-Ecological Systems. Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Berkes, F.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. (Eds.) Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003.

- Lemos, M.C.; Agrawal, A. Environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.; Elmqvist, T.; Gunderson, L.; Holling, C.S.; Walker, B. Resilience and sustainable development: Building adaptive capacity in a world of transformations. AMBIO 2002, 5, 437–440. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J. Social capital and the collective management of resources. Science 2003, 5652, 1912–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Smith, D. Social capital in biodiversity conservation and management. Cons. Biol. 2004, 3, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Ward, H. Social capital and the environment. World Dev. 2001, 2, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Johansson, K. Trust-building, knowledge generation and organizational innovations: The role of a bridging organization for adaptive co-management of a wetland landscape around Kristianstad, Sweden. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 34, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondizio, E.S.; Ostrom, E.; Young, O.R. Connectivity and the governance of multilevel social- ecological systems: The role of social capital. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.; Arnold, G.; Tomás, S.V. A review of design principles for community-based natural resource management. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 4. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art38/ (accessed on 4 July 2014).

- Ostrom, V. Polycentricity (Part 1). In Polycentricity and Local Public Economics; McGinnis, M., Ed.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1999; pp. 52–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius, C.; Folke, C.; Cundill, G.; Schultz, L. Powerless spectators, coping actors, and adaptive co-managers: A synthesis of the role of communities in ecosystem management. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 1. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss1/art15/ (accessed on 4 July 2014).

- Natcher, D.C.; Davis, S.; Hickey, C.G. Co-management: Managing relationships, not resources. Hum. Organ. 2005, 3, 240–250. [Google Scholar]

- FC (Forestry Commission). National Forest Plantation Development Programme (NFPDP): Annual Report 2013. Available online: http://www.fcghana.org/assets/file/Publications/Forestry_Issues/National%20Forest%20Plantaion%20Development%20Programme/Annual%20Reports/nfpdp_annual%20report_2012.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2014).

- Fumey Nassah, V.; Resource Management Support Centre, Kumasi, Ashanti region, Ghana. Personal communication, 2012.

- Winjum, J.K.; Schroeder, P.E. Forest plantations of the world: Their extent, ecological attributes, and carbon storage. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1997, 1, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran Nair, P.K.; Mohan Kumar, B.; Nair, V.D. Agroforestry as a strategy for carbon sequestration. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2009, 172, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasco, R.D.; Delfino, R.J.P.; Espaldon, M.L.O. Agroforestry systems: Helping smallholders adapt to climate risks while mitigating climate change. WIRES Clim. Chang. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, D.; Burton, A.J.; Storer, A.J.; Opuni-Frimpong, E. Variation in wood density and carbon content of tropical plantation tree species from Ghana. New For. 2014, 1, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, P.E. Carbon storage potential of short rotation tree plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 1992, 50, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfo, E.; Acheampong, E.; Opuni-Frimpong, E. Fractured tenure, unaccountable authority, and benefit capture: Constraints to improving community benefits under climate change mitigation schemes in Ghana. Cons. Soc. 2012, 2, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfo, E. Security of Tenure and Community Benefits under Collaborative Forest Management Arrangements in Ghana: A Country Report; CSIR-INSTI: Accra, Ghana, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, V.K.; Marfo, K.A.; Kasanga, K.R.; Danso, E.; Asare, A.B.; Yeboah, O.M.; Agyeman, F. Revising the taungya plantation system: New revenue-sharing Proposal from Ghana. Unasylva 2003, 1, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, V.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.F.; Dietz, T. A fine mess: Bricolaged forest governance in Cameroon. Int. J. Commons. 2014. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- FC (Forestry Commission). National Forest Plantation Development Programme (NFPDP): Annual Report 2008. Available online: http://theredddesk.org/sites/default/files/nfpdp_annual_report_20081_2.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2014).

- MLNR (Ministry of Land and Natural Resources) Climate Investment Funds. Forest Investment Program. Ghana Investment Plan, 2012. Available online: https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/cif/sites/climateinvestmentfunds.org/files/FIP_5_Ghana.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2014).

- Wiersum, K.F.; Lescuyer, G.; Nketiah, K.S.; Wit, M. International forest governance regimes: Reconciling concerns on timber legality and forest-based livelihoods. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 32, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Communities of practice. A brief introduction. Available online: http://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/06-Brief-introduction-to-communities-of-practice.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2014).

- Bormann, B.T.; Haynes, R.W.; Martin, J.R. Adaptive management of forest ecosystems: Did some rubber hit the road? BioScience 2007, 57, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkyi, M.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.F.; Kyereh, B.; Dietz, T. Fighting over forest: Toward a shared analysis of livelihood conflicts and conflict management in Ghana. Soc. Natur. Resour. 2013, 3, 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Yasmi, Y.; Kelley, L.; Enters, T. Forest Conflict in Asia and the Role of Collective Action in Its Management; CAPRI Working Paper No.102; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Conference Organizing Committee. The Kumasi Resolution 2014. In Presented at the First National Forestry Conference, The Contribution of Forests to Ghana’s Economic Development, Kumasi, Ghana, 16–18 September 2014.

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ros-Tonen, M.A.F.; Derkyi, M.; Insaidoo, T.F.G. From Co-Management to Landscape Governance: Whither Ghana’s Modified Taungya System? Forests 2014, 5, 2996-3021. https://doi.org/10.3390/f5122996

Ros-Tonen MAF, Derkyi M, Insaidoo TFG. From Co-Management to Landscape Governance: Whither Ghana’s Modified Taungya System? Forests. 2014; 5(12):2996-3021. https://doi.org/10.3390/f5122996

Chicago/Turabian StyleRos-Tonen, Mirjam A. F., Mercy Derkyi, and Thomas F. G. Insaidoo. 2014. "From Co-Management to Landscape Governance: Whither Ghana’s Modified Taungya System?" Forests 5, no. 12: 2996-3021. https://doi.org/10.3390/f5122996

APA StyleRos-Tonen, M. A. F., Derkyi, M., & Insaidoo, T. F. G. (2014). From Co-Management to Landscape Governance: Whither Ghana’s Modified Taungya System? Forests, 5(12), 2996-3021. https://doi.org/10.3390/f5122996