Forest Policy and Law for Sustainability within the Korean Peninsula

Abstract

:1. Introduction

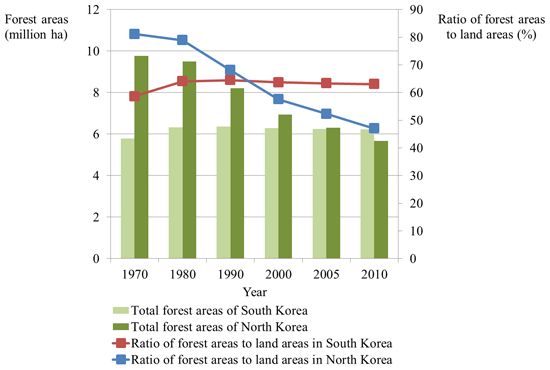

2. Deforestation and Reforestation in the Korean Peninsula

| Condition | South Korea | North Korea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land area (thousand ha) | 9873 | 12,041 | |

| Forest area (thousand ha) | 6222 | 5666 | |

| Forest ownership (% of forest area) | Public | 31 | 100 |

| Forest characteristics (thousand ha/ % of forest area) | Primary forest | 2957/48 | 780/14 |

| Content | Year | South Korea | North Korea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area of planted forest (1000 ha) | 1990 | - | 1130 | |

| 2000 | 1738 | 955 | ||

| 2005 | 1781 | 868 | ||

| 2010 | 1823 | 781 | ||

| Annual change rate | 1990–2000 | 1000 ha/year | - | −18 |

| % | - | −1.67 | ||

| 2000–2005 | 1000 ha/year | 9 | −17 | |

| % | 0.49 | −1.89 | ||

| 2005–2010 | 1000 ha/year | 8 | −17 | |

| % | 0.47 | −2.09 | ||

3. Korean Forest Policies

3.1. Changes of South Korean Forest Policies

3.1.1. Phase I: Post-War Forestland Recovery and Wood Supply (1953–1972)

3.1.2. Phase II: Forest Rehabilitation (1973–1997)

3.1.3. Phase III: Sustainable Forest Management (1998–2013)

3.2. Changes in North Korean Forest Policies

3.2.1. Phase I: Post-War Forestland Recovery and Wood Supply (1953–1975)

3.2.2. Phase II: Terraced Upland Cultivation (1976–1991)

3.2.3. Phase III: Land Protection and Greening (1992–2013)

3.3. Comparison of South Korean and North Korean Forest Policies

| Title of International Forest-Related Treaties | Signature Date | |

|---|---|---|

| South Korea | North Korea | |

| Convention on Biodiversity (1992) | 13 June 1992 (signed) 3 October 1994 (ratified) | 11 June 1992 (signed) 26 October 1994 (approved) |

| United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992) | 13 June 1992 (signed) 14 December 1993 (ratified) | 11 June 1992 (signed) 5 December 1994 (ratified) |

| Kyoto Protocol (1997) | 25 September 1998 (signed) 8 November 2002 (ratified) | 27 April 2005 (ratified) |

| Convention to Combat Desertification (1992) | 14 October 1994 (signed) 17 August 1999 (ratified) | 29 December 2003 (ratified) |

| International Tropical Timber Agreement (1994) | 12 September 1995 (signed and ratified) | None |

| Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species (1979) | 9 July 1993(accessioned) | None |

4. Korean Laws

4.1. South Korean Forest Laws

4.2. North Korean Forest Laws

4.3. Comparison of South and North Korean Forest Laws

| Framework Act on Forest in South Korea | Forest Act in North Korea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chapter | Content | Article number | Chapter | Content | Article number |

| General provisions | Basic principles and responsibilities of governments | 1–4 | Basic provisions | Forest ownership, national plan for forest construction, international cooperation, forest management principles | 1–9 |

| Basic directions | Conservation and use of forests, international cooperation and preparation of unification | 5–9 | |||

| Basic forest policies | Basic and regional forest plans | 10–12 | Creation of forests | Expanding forest areas and producing seedlings | 10–18 |

| Conservation and use of forest | Policies concerning forest disasters and Sustainable forest management | 13–16 | Forest protection | Prevention of forest fires, forest pest control and protection of forest resources | 19–27 |

| Chapter | Content | Article number | Chapter | Content | Article number |

| Promotion functions of public interests of forests | Urban forest management and forest recreation | 17–20 | Forest resource utilization | Forest land use and use of timber and non-timber products | 28–38 |

| Promotion of forestry | Forestry productivities and forestry technology | 21–26 | |||

| National forest management and development of mountain villages | Policies for national forest management and mountain villages | 27–30 | Rule and control of forest management | Rule and control of forest project management | 39–49 |

5. Basic Principles for Sustainable Forest Policy and Law after Korean Unification

5.1. Basic Principles of Korean Forest Policy

5.2. Basic Principles of Korean Forest Law

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992. Available online: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/conf151/aconf15126-3annex3.htm (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- Häusler, A.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M. Sustainable Forest Management in Germany: The Ecosystem Approach of the Biodiversity Convention Reconsidered; Federal Ministry of Environment: Bonn, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, O.; Macpherson, A.J.; Alavalapati, J. Toward a Policy of Sustainable Forest Management in Brazil: A Historical Analysis. J. Environ. Dev. 2009, 18, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rametsteiner, E.; Simula, M. Forest certification—An instrument to promote sustainable forest management? J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 67, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside, P.M. Deforestation in Brazilian Amazonia: History, rates, and consequences. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyfroidt, P.; Lambin, E.F. Forest transition in Vietnam and its environmental impacts. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2008, 14, 1319–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbu, G.A.; Swallow, B.M.; Thompson, D.Y. Locating REDD: A global survey and analysis of REDD readiness and demonstration activities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 14, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.S.; Joo, R.W.; Kim, Y.-S. Forest transition in South Korea: Reality, path and drivers. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, Y.C.; Park, D.K. Comparative study on forest policy in South and North Koreas. In Comparative Study on Environmental Policy in South and North Koreas; Seoul National University Press: Seoul, South Korea, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 5–110. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Engler, R.; Teplyakov, V.; Adams, J.M. An Assessment of Forest Cover Trends in South and North Korea, from 1980 to 2010. Environ. Manag. 2014, 53, 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2010. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i1757e/i1757e.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- Kang, S.; Choi, W. Forest cover changes in North Korea since the 1980s. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2014, 14, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.B.; Kim, N.S.; Choe, H.S.; Shin, K.H.; Kang, C.S.; Han, U. Landscape fragmentation of forest of the cropland increase using landsat images of Manpo and Gangae, Jagang Cities, Northwest Korea. J. Korean Assoc. Reg. Geogr. 2003, 9, 481–492. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.B. Analysis on the Environmental Change and Natural Hazard in North Korea; Hanul: Paju, South Korea, 2006. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.B.; Jin, S. A study on characteristics of the spatial distribution of the cropland and forest by the cultivation expansion in North Korea. J. Korean Geomorphol. Assoc. 2008, 15, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H. A study on ecological restoration measures for the degraded land in North Korea: focusing on South Korea’s restoration policy. North Korean Stud. Rev. 2005, 9, 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.S.; Park, S.Y. The rehabilitation of North Korea’s devastated forest with the focus on the case of South Korea. North Korean Studies. 2012, 8, 133–159. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.H.; Han, C.W. A study on the comparison of forest legal system of North and South Korea and the ways of integration. Unification Law 2012, 10, 147–175. [Google Scholar]

- Teplyakov, V.K.; Kim, S.I. North Korea Reforestation: International Regime and Domestic Opportunities; Jungmin Publishing Co.: Seoul, South Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Noronha, R. Why is it so difficult to grow fuelwood. Unasylva 1981, 33, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.R. Plan B 3.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization; W. W. Norton: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Youn, Y.; Park, M. Factors affecting success in transition for sustainable forestry: Case of Korea. Int. Forest. Rev. 2010, 15, 247. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Youn, Y. Policy integration for reforestation in the Republic of Korea. In Proceeding of the International Symposium on Transition to Sustainable Forest Management and Rehabilitation: The Enabling Environment and Roadmap, Beijing, China, 21–23 October 2013; pp. 86–89.

- Lee, D.K. (Ed.) Korean Forests: Lessons Learned From Stories of Success and Failure; Korea Forest Research Institute: Seoul, South Korea, 2010.

- Maplecroft. Climate Change and Environmental Risk Atlas 2012; Maplecroft: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, J.H.; Koo, J.C.; Youn, Y.C. Economic feasibility of REDD project for preventing deforestation in North Korea. J. Forest Soc. 2011, 100, 630–638. [Google Scholar]

- Youn, Y.C.; Park, D.K.; Park, C.H.; Chon, H.T.; Choe, J.; Heo, E.Y.; Yun, S.J. Comparative Study on Environmental Policy in South and North Koreas; Seoul National University Press: Seoul, South Korea, 2008; Volume 1. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Gangwon Province Inter-Korea Exchange and Cooperation. The Ten Year-History of Gangwon Province’s Inter-Korea Exchange and Cooperation; Gangwon Province Inter-Korea Exchange and Cooperation: Chuncheon, South Korea, 2010. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kang, G. Five-Year Economic Development Plans; Seoul National University Press: Seoul, South Korea, 2000. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.K.; Shin, J.H.; Park, P.S.; Park, Y.D. Forest rehabilitation in Korea. In Korean Forests: Lessons Learned from Stories of Success and Failure; Lee, D.K., Ed.; Korea Forest Research Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2010; pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Kwon, G.; Park, G.; Park, M.; Park, H.; Bae, I.; Oh, S.; Youn, Y.; Lee, S. Analysis of Korean Successful Case of Reforestation; Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, South Korea, 2009. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Korea Forest Service. The 50-year History of Korea Forest Policy; Korea Forest Service: Seoul, South Korea, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.B.; Bae, J.S. Factors of success of the clearance policy for slash-and-burn fields in the 1970. J. Korean For. Soc. 2007, 96, 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- The US dollar to Korean won exchange rate. Available online: http://www.index.go.kr (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- Bae, S.W. Reforestation; National Museum of Korean Contemporary History: Seoul, South Korea, 2013. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Youn, Y. Development of urban forest policy-making toward governance in the Republic of Korea. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.; Park, M.; Youn, Y. Preferences of urban dwellers on urban forest recreational services in South Korea. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Forest Service. Statistical Yearbook of Forestry; Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, South Korea, 2012. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Sukhdev, O. Overview of the Republic of Korea’s National Strategy for Green Growth; United Nations Development Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: http://www.unep.org/PDF/PressReleases/201004_unep_national_strategy.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2014).

- Park, M.; Youn, Y. Development of South Korean REDD+ strategies for forest carbon credits. J. Environ. Policy Admin. 2012, 20, 19–48. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Youn, Y. Legal institutions for enhancing and protecting forests as a carbon sink in Japan and the Republic of Korea. For. Sci. Technol. 2013, 9, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.; Lee, S.; Park, S. A study on the North Korea’s change of forest policy since the economic crisis in 1990s. Korean J. Unification Aff. 2009, 21, 459–492. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Y.S. An outcome of nature-reorganization policy in North Korea. North Korean Stud. 2008, 4, 103–128. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, B.I. Chronological Changes in Forestry and Related Laws in North Korea; Korea Forest Research Institute: Seoul, South Korea, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.B.; Kim, N.S.; Kang, C.; Shin, K.H.; Choe, H.S.; Han, U. Estimation of soil loss due to cropland increase in Hoeryeung, Northeast Korea. J. Korean Assoc. Reg. Geogr. 2003, 9, 373–384. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Park, M.; Youn, Y. Forest policy of Democratic People’s Republic of Korea represented in Rodong Shinmun. J. Environ. Policy 2012, 11, 123–148. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Han, W. More Trees for the Future of a Rich and Powerful Country. Rodong Shinmun 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.J. Establishing 65 Thousand of Forests in 2007. Rodong Shinmun 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Youn, Y.H. Establishing Forests Hardly. Rodong Shinmun 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rodong Shinmun. Kim Jong IL Guided the Tree Nursery of Forest Management Office at Liwon County, Hamkyoungnamdo. Rodong Shinmun 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.I. The pride of greening and gardening. Rodong Shinmun 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.K. Sustainable reforestation in North Korea. In Proceeding of the 2014 International Symposium for Green Asia Organization Foundation, Seoul, South Korea, 19 March 2014; pp. 89–101.

- Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Ministry of Land and Environment Protection. DPRK’s first national communication under the framework convention on climate change. Available online: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/prknc1.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- Teplyakov, V.K. North Korea in the UN system and international projects. In North Korea Reforestation: International Regime and Domestic Opportunities; Teplyakov, V.K., Kim, S.I., Eds.; Jungmin Publishing Co.: Seoul, Korea, 2012; pp. 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Ministry of Land and Environment Protection. Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Environment and Climate Change Outlook; United Nations Environment Programme: Pyongyang, North Korea, 2012. Available online: http://www.unep.org/dewa/portals/67/pdf/ECCO_DPRK.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2014).

- Habib, B. Why Is the DPRK Pursuing CDM Carbon Credits? North Korean Economy Watch 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. Case study of environmental agreements between South and North Korea. Unification Law 2013, 15, 137–156. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Convention on Biological Diversity. Available online: http://www.cbd.int/information/parties.shtml (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- International Tropical Timber Agreement from United Nations Treaty Collection. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XIX-39&chapter=19&lang=en (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Available online: http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/parties/alphabet.php (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available online: http://unfccc.int/parties_and_observers/parties/items/2352.php (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. Available online: http://www.unccd.int/en/about-the-convention/Official-contacts/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- Lee, H. Understanding Korean Unification Law; Parkyoungsa: Seoul, South Korea, 2014. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Unification. History of Inter-Korean Relations, South Korea. Available online: http://eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do?menuCd=DOM_000000202002001000 (accessed on 15 July 2014).

- Lim, P.S.; Lee, J.H. Policy proposal for unification of the Korean military integration: Based on post-merger integration (PMI) with organization culture analysis. Quart. J. Def. Policy Stud. 2013, 100, 139–170. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y. The directions of Social Security Acts after the reunification of Korea. World Const. Law Rev. 2013, 19, 117–146. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.C. A study on the land policy for the North Korean region of the Unified Korean peninsula. Korean Apprais. Rev. 2012, 22, 129–158. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Yun, G. Land ownership system of North Korea and the use rights of the land in North Korea in terms of the reunification of the legal system of North and South Korea. Law Rev. 2012, 47, 123–149. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.W. Reorganization direction of real estate ownership system in Unified Korea: Focusing on land and housing. J. Law 2013, 21, 81–99. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.S.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, C.C.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.H. Estimating the spatial distribution of forest stand volume in Gyeonggi Province using National Forest Inventory data and forest type map. J. Korean Forest Soc. 2010, 99, 827–835. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, F.; Geneletti, D. Identifying priority areas for forest landscape restoration in Chiapas (Mexico): An operational approach combining ecological and socioeconomic criteria. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 41 of 1999. Available online: http://theredddesk.org/sites/default/files/uu41_99_en.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- National Legal Information Center, Korea Ministry of Governmental Legislation. Available online: http://www.law.go.kr/main.html (accessed on 8 August 2014).

- North Korea Laws Information Center, Korea Ministry of Governmental Legislation. Available online: http://world.moleg.go.kr/KP (accessed on 8 August 2014).

Appendix

| Title of acts | Enactment date |

|---|---|

| Forest Product Control Act * | 27 June 1961 |

| Forest Law * | 27 December 1961 |

| Erosion Control Act | 15 January 1962 |

| Abolishment of Slash-and-Burn Fields Act * | 23 April 1966 |

| Act on Arrangement of Special Employees for Forest Protection | 9 February 1963 |

| National Forestry Cooperatives Federation Act | 4 January 1980 |

| Natural Parks Act | 4 January 1980 |

| Natural Environment Conservation Act | 31 December 1991 |

| Act on Promotion of Forestry and Mountain Villages | 10 April 1997 |

| Framework Act on Forest | 24 March 2001 |

| Act on Establishment and Promotion of Forest Arboretums | 28 May 2001 |

| Forest Land Management Act | 30 December 2002 |

| Baekdudaegan Protection Act | 31 December 2003 |

| Wildlife Protection and Management Act | 9 February 2004 |

| Pine Wilt Disease Prevention Act | 31 May 2005 |

| Forest Culture and Recreation Act | 4 August 2005 |

| National Forest Management Act | 4 August 2005 |

| Establishment and Management of Forest Resource Act | 4 August 2005 |

| Act on Structural Improvement of National Forestry Cooperatives Federation | 3 August 2004 |

| Forest Protection Act | 9 June 2009 |

| Act on the Promotion of Maintaining and Enhancing Carbon Sinks | 22 February 2012 |

| Act on the Sustainable Use of Timbers | 24 May 2013 |

| Special Act on Forest Land Management in Northern Districts of the Civilian Control Line | 14 January 2014 |

| Forest Education Promotion Act | 18 March 2014 |

| Title of acts | Enactment date |

|---|---|

| Act on Land Reform * | 5 March 1946 |

| Land Law | 29 April 1977 |

| Environmental Protection Law | 9 April 1986 |

| Forest Act | 11 December 1992 |

| Control Law on Land and Environmental Protection | 27 May 1998 |

| Act on Green Spaces (Won-rim) | 25 November 2010 |

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, M.S.; Lee, H. Forest Policy and Law for Sustainability within the Korean Peninsula. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5162-5186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6085162

Park MS, Lee H. Forest Policy and Law for Sustainability within the Korean Peninsula. Sustainability. 2014; 6(8):5162-5186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6085162

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Mi Sun, and Hyowon Lee. 2014. "Forest Policy and Law for Sustainability within the Korean Peninsula" Sustainability 6, no. 8: 5162-5186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6085162

APA StylePark, M. S., & Lee, H. (2014). Forest Policy and Law for Sustainability within the Korean Peninsula. Sustainability, 6(8), 5162-5186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6085162