Sea Ice Extent Detection in the Bohai Sea Using Sentinel-3 OLCI Data

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Data

3. Methods

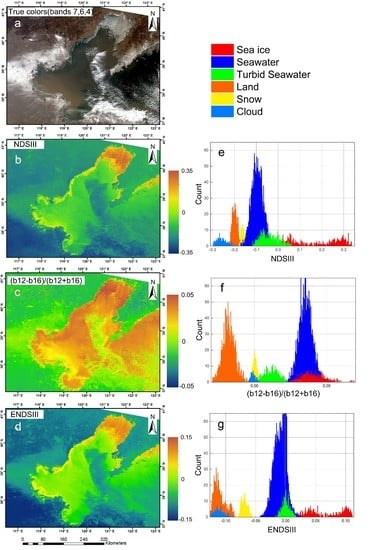

3.1. Normalized Difference Sea Ice Information Index

3.2. Enhanced Normalized Difference Sea Ice Information Index

3.3. Determinaton of Threshold Values

3.4. Normalized Difference Snow Index

3.5. Support Vector Machine Classifier

4. Results

4.1. Sea Ice Detection and Validation

4.2. Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Bohai Sea Ice in the 2017–2018 Winter

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ning, L.; Xie, F.; Gu, W.; Xu, Y.; Huang, S.; Yuan, S.; Cui, W.; Levy, J. Using remote sensing to estimate sea ice thickness in the Bohai Sea, China based on ice type. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 4539–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J. Monitoring the Spatiotemporal Evolution of Sea Ice in the Bohai Sea in the 2009–2010 Winter Combining MODIS and Meteorological Data. Estuaries Coasts 2012, 35, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, M. Sea ice properties in the Bohai Sea measured by MODIS-Aqua: 1. Satellite algorithm development. J. Mar. Syst. 2012, 95, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Hui, F.; Zhu, L.; Cheng, X.; Cheng, B.; Shokr, M.; Zhao, J.; Ding, M.; Zeng, T. The spatiotemporal patterns of sea ice in the Bohai Sea during the winter seasons of 2000–2016. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2017, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Meng, J.; Xie, Q. PCA-based sea-ice image fusion of optical data by HIS transform and SAR data by wavelet transform. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2015, 34, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleti, P.R.; Luis, A.J. Sea ice observations in polar regions: Evolution of technologies in remote sensing. Int. J. Geosci. 2013, 4, 1031–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvonen, J. Baltic sea ice concentration estimation based on C-band dual-polarized SAR data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 5558–5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, N.; Pedersen, L.; Tonboe, R.; Kern, S.; Heygster, G.; Lavergne, T.; Sørensen, A.; Saldo, R.; Dybkjær, G.; Brucker, L. Inter-comparison and evaluation of sea ice algorithms: Towards further identification of challenges and optimal approach using passive microwave observations. Cryosphere 2015, 9, 1797–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavergne, T.; Macdonald Sørensen, A.; Kern, S.; Tonboe, R.; Notz, D.; Aaboe, S.; Bell, L.; Dybkjær, G.; Eastwood, S.; Gabarro, C.; et al. Version 2 of the EUMETSAT OSI SAF and ESA CCI sea-ice concentration climate data records. Cryosphere 2019, 13, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meier, W.N.; Fetterer, F.; Stewart, J.S.; Helfrich, S. How do sea-ice concentrations from operational data compare with passive microwave estimates? Implications for improved model evaluations and forecasting. Ann. Glaciol. 2015, 56, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agnew, T.; Howell, S. The use of operational ice charts for evaluating passive microwave ice concentration data. Atmosphere-Ocean 2003, 41, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.; Eriksson, L.E.B. SAR algorithm for sea ice concentration—Evaluation for the Baltic Sea. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2012, 9, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Clausi, D.A. Unsupervised segmentation of synthetic aperture radar sea ice imagery using a novel Markov random field model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2005, 43, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, P.; Light, B.; Eicken, H.; Haller, M. Mapping sediment-laden sea ice in the Arctic using AVHRR remote-sensing data: Atmospheric correction and determination of reflectances as a function of ice type and sediment load. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 107, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, M. Sea ice properties in the Bohai Sea measured by MODIS-Aqua: 2. Study of sea ice seasonal and interannual variability. J. Mar. Syst. 2012, 95, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Liu, C.; Liu, X. Practical Model of Sea Ice Thickness of Bohai Sea Based on MODIS Data. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drüe, C.; Heinemann, G. High-resolution maps of the sea-ice concentration from MODIS satellite data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ke, C.; Sun, B.; Lei, R.; Tang, X. Extraction of sea ice concentration based on spectral unmixing method. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2011, 5, 053552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sheng, H.; Zhang, X. Sea ice thickness estimation in the Bohai Sea using geostationary ocean color imager data. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2016, 35, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Meng, J.; Wang, N.; Cao, Y. Sea ice drift tracking in the Bohai Sea using geostationary ocean color imagery. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2014, 8, 083650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Huang, K.; Shao, D.; Xu, Y.; Gu, W. Monitoring the Characteristics of the Bohai Sea Ice Using High-Resolution Geostationary Ocean Color Imager (GOCI) Data. Sustainability 2019, 11, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Qiu, Y. Reducing the impact of thin clouds on Arctic Ocean sea ice concentration from FengYun-3 MERSI data single cavity. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 16341–16348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, Y. Using MODIS data to estimate sea ice thickness in the Bohai Sea (China) in the 2009–2010 winter. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, L. Improving MODIS sea ice detectability using gray level co-occurrence matrix texture analysis method: A case study in the Bohai Sea. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2013, 85, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, Z.; Wang, J. Sea ice detection based on an improved similarity measurement method using hyperspectral data. Sensors 2017, 17, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, C.; Bernier, M.; Chokmani, K.; Poulin, J. IceMap250—Automatic 250 m sea ice extent mapping using MODIS data. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Yan, X. Classification of MODIS images combining surface temperature and texture features using the Support Vector Machine method for estimation of the extent of sea ice in the frozen Bohai Bay, China. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 36, 2734–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q. Detection of sea ice in sediment laden water using MODIS in the Bohai Sea: A CART decision tree method. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 36, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toming, K.; Kutser, T.; Uiboupin, R.; Arikas, A.; Vahter, K.; Paavel, B. Mapping water quality parameters with sentinel-3 ocean and land colour instrument imagery in the Baltic Sea. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lyu, H.; Liu, G.; Zheng, Z.; Du, C.; Mu, M.; Xu, J.; Lei, S.; et al. Inland Water Atmospheric Correction Based on Turbidity Classification Using OLCI and SLSTR Synergistic Observations. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lyu, H.; Miao, S.; Pan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q. A two-step approach to mapping particulate organic carbon (POC) in inland water using OLCI images. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 90, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, F.; Zóltak, M.; Pipitone, C.; Zappa, L.; Wenng, H.; Immitzer, M.; Weiss, M.; Baret, F.; Atzberger, C. Data service platform for Sentinel-2 surface reflectance and value-added products: System use and examples. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, G.A.; Hall, D.K.; Ackerman, S.A. Sea ice extent and classification mapping with the moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer airborne simulator. Remote Sens. Environ. 1999, 68, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenks, G.F. The data model concept in statistical mapping. Int. Yearb. Cartogr. 1967, 7, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier, J. Spectral signature of alpine snow cover from the landsat thematic mapper. Remote Sens. Environ. 1989, 28, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burges, C.J.C. A tutorial on support vector machines for pattern recognition. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 1998, 2, 121–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.N. An overview of statistical learning theory. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1999, 10, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, J.; Watkins, C. Support vector machines for multi-class pattern recognition. In Proceedings of the 7th European Symposium on Artificial Neural Networks (ESANN-99), Bruges, Belgium, 21–24 April 1999; Volume 99, pp. 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H. Compare different levels of fusion between optical and SAR data for impervious surfaces estimation. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Earth Observation and Remote Sensing Applications, EORSA 2012, Shanghai, China, 8–11 June 2012; pp. 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Gu, W.; Liu, C.; Xie, F. Towards a semi-empirical model of the sea ice thickness based on hyperspectral remote sensing in the Bohai Sea. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2017, 36, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Band Number | Central Wavelength (nm) | Full Width at Half Maximum (nm) | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band 1 | 400 | 15 | 2188 |

| Band 2 | 412.5 | 10 | 2061 |

| Band 3 | 442.5 | 10 | 1811 |

| Band 4 | 490 | 10 | 1541 |

| Band 5 | 510 | 10 | 1488 |

| Band 6 | 560 | 10 | 1280 |

| Band 7 | 620 | 10 | 997 |

| Band 8 | 665 | 10 | 883 |

| Band 9 | 673.75 | 7.5 | 707 |

| Band 10 | 681.25 | 7.5 | 745 |

| Band 11 | 708.75 | 10 | 785 |

| Band 12 | 753.75 | 7.5 | 605 |

| Band 13 | 761.25 | 2.5 | 232 |

| Band 14 | 764.375 | 3.75 | 305 |

| Band 15 | 767.5 | 2.5 | 330 |

| Band 16 | 778.75 | 15 | 812 |

| Band 17 | 865 | 20 | 666 |

| Band 18 | 885 | 10 | 395 |

| Band 19 | 900 | 10 | 308 |

| Band 20 | 940 | 20 | 203 |

| Band 21 | 1020 | 40 | 152 |

| Ground Truth | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea Ice | Other | Total | Commission Error | |||

| Map | Sea Ice | 89 | 11 | 100 | 11.00% | |

| Other | 35 | 754 | 789 | 4.44% | ||

| Total | 124 | 765 | 889 | |||

| Omission Error | 28.23% | 1.44% | Overall Accuracy | |||

| Kappa | 76.54% | 94.83% | ||||

| Map | Sea Ice | 94 | 35 | 129 | 27.13% | |

| Other | 30 | 730 | 760 | 3.95% | ||

| Total | 124 | 765 | 889 | |||

| Omission Error | 24.19% | 4.58% | Overall Accuracy | |||

| Kappa | 70.05% | 92.69% | ||||

| NDSI | Map | Sea Ice | 107 | 77 | 184 | 41.85% |

| Other | 18 | 798 | 816 | 2.21% | ||

| Total | 125 | 875 | 1000 | |||

| Omission Error | 14.40% | 8.80% | Overall Accuracy | |||

| Kappa | 63.88% | 90.50% | ||||

| SVM | Map | Sea Ice | 97 | 19 | 116 | 16.38% |

| Other | 28 | 762 | 790 | 3.54% | ||

| Total | 125 | 781 | 906 | |||

| Omission Error | 22.40% | 2.43% | Overall Accuracy | |||

| Kappa | 77.51% | 94.81% | ||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, H.; Ji, B.; Wang, Y. Sea Ice Extent Detection in the Bohai Sea Using Sentinel-3 OLCI Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2436. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11202436

Su H, Ji B, Wang Y. Sea Ice Extent Detection in the Bohai Sea Using Sentinel-3 OLCI Data. Remote Sensing. 2019; 11(20):2436. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11202436

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Hua, Bowen Ji, and Yunpeng Wang. 2019. "Sea Ice Extent Detection in the Bohai Sea Using Sentinel-3 OLCI Data" Remote Sensing 11, no. 20: 2436. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11202436

APA StyleSu, H., Ji, B., & Wang, Y. (2019). Sea Ice Extent Detection in the Bohai Sea Using Sentinel-3 OLCI Data. Remote Sensing, 11(20), 2436. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11202436