Infant Cereals: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Opportunities for Whole Grains

Abstract

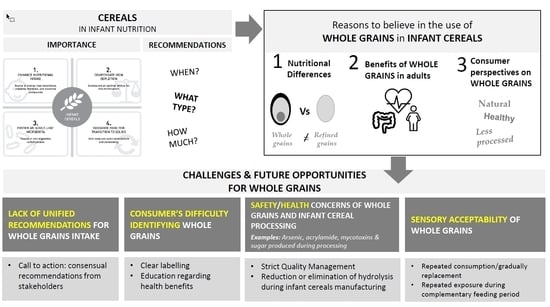

:1. Introduction

2. Recommendations for Infant Cereal Intake

3. Reasons to Believe in the Use of Whole Grains in Infant Cereals

3.1. Nutritional Differences between Whole Grains and Refined Cereals

3.2. Benefits of Whole Grain Consumption

3.3. Consumer Perspectives on Whole Grains

4. Challenges and Future Opportunities

4.1. Lack of Unified Recommendations for Whole Grain Intake

4.2. Consumer Difficulty Identifying Whole Grains

4.3. Safety and Health Concerns of Whole Grains and Infant Cereal Processing

4.3.1. Safety Concerns of Whole Grain Infant Cereals

4.3.2. Sugar-Related Concern in Infant Cereals

4.4. Sensory Acceptability of Whole Grain Cereals

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Definition and Classification of Commodities: Cereals and Cereal Products. Available online: http://www.fao.org/es/faodef/fdef01e.htm (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Serna-Saldivar, S.O. Cereal grains. In Cereal Grains: Properties, Processing, and Nutritional Attributes; CRC Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–40. ISBN 9781439815601. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kamp, J.W.; Poutanen, K.; Seal, C.J.; Richardson, D.P. The HEALTHGRAIN definition of ‘whole grain’. Food Nutr. Res. 2014, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Cereals, Starchy Roots and Other Mainly Carbohydrate Foods. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/W0073e/w0073e06.htm#P5424_644009 (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Commission Directive 2006/125/EC of 5 December 2006 on processed cereal-based foods and baby foods for infants and young children (Codified version). Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 339, 16–35.

- Codex Alimentarius CODEX STAN 74-1981. Standard for Processed Cereal-Based Foods for Infants and Young Children. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCODEX%2BSTAN%2B74-1981%252FCXS_074e.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Freeman, V.; van’t Hof, M.; Haschke, F.; Euro-Growth Study Group. Patterns of milk and food intake in infants from birth to age 36 months: The Euro-growth study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2000, 31, S76–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butte, N.F.; Fox, M.K.; Briefel, R.R.; Siega-Riz, A.M.; Dwyer, J.T.; Deming, D.M.; Reidy, K.C. Nutrient intakes of US infants, toddlers, and preschoolers meet or exceed dietary reference intakes. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, S27–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siega-Riz, A.M.; Deming, D.M.; Reidy, K.C.; Fox, M.K.; Condon, E.; Briefel, R.R. Food consumption patterns of infants and toddlers: Where are we now? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, S38–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, C.; Visalli, M.; Jacob, S.; Chabanet, C.; Schlich, P.; Nicklaus, S. Maternal feeding practices during the first year and their impact on infants’ acceptance of complementary food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 29, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostoni, C.; Decsi, T.; Fewtrell, M.; Goulet, O.; Kolacek, S.; Koletzko, B.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Moreno, L.; Puntis, J.; Rigo, J.; et al. Complementary feeding: A commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2008, 46, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardet, A. New hypotheses for the health-protective mechanisms of whole-grain cereals: What is beyond fiber? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2010, 23, 65–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, K.; Callen, C.; Bhatia, J.; Reidy, K.; Bechard, L.J.; Carvalho, R. Importance of dietary sources of iron in infants and toddlers: Lessons from the FITS study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimes, C.A.; Szymlek-Gay, E.A.; Campbell, K.J.; Nicklas, T.A. Food sources of total energy and nutrients among US infants and toddlers: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2012. Nutrients 2015, 7, 6797–6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domellöf, M.; Braegger, C.; Campoy, C.; Colomb, V.; Decsi, T.; Fewtrell, M.; Hojsak, I.; Walter, M.; Molgaard, C.; Shamir, R.; et al. Iron requirements of infants and toddlers. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 58, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallani, M.; Amarri, S.; Uusijarvi, A.; Adam, R.; Khanna, S.; Aguilera, M.; Vieites, J.M.; Norin, E.; Young, D.; Scott, J.A. Determinants of the human infant intestinal microbiota after the introduction of first complementary foods in infant samples from five European centres. Microbiology 2011, 157, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gamage, H.K.; Tetu, S.G.; Chong, R.W.; Ashton, J.; Packer, N.H.; Paulsen, I.T. Cereal products derived from wheat, sorghum, rice and oats alter the infant gut microbiota in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, M.J.; Periago, M.J.; Martínez, R.; Ortuño, I.; Sánchez-Solís, M.; Ros, G.; Romero, F.; Abellán, P. Effects of infant cereals with different carbohydrate profiles on colonic function—Randomised and double-blind clinical trial in infants aged between 6 and 12 months—Pilot study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013, 172, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakashita, R.; Inoue, N.; Tatsuki, T. Selection of reference foods for a scale of standards for use in assessing the transitional process from milk to solid food in infants and pre-school children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 57, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicklaus, S.; Demonteil, L.; Tournier, C. Modifying the texture of foods for infants and young children. In Modifying Food Texture; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 187–222. ISBN 978-1-78242-334-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fewtrell, M.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; Domellöf, M.; Embleton, N.; Fidler Mis, N.; Hojsak, I.; Hulst, J.M.; Indrio, F.; Lapillonne, A.; et al. Complementary feeding: A position paper by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific Opinion on nutrient requirements and dietary intakes of infants and young children in the European Union. EFSA J. 2013, 11, 3408. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/3408 (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Cereal in a Bottle: Solid Food Shortcuts to Avoid. Available online: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/baby/feeding-nutrition/Pages/Cereal-in-a-Bottle-Solid-Food-Shortcuts-to-Avoid.aspx (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Starting Solid Foods. Available online: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/baby/feeding-nutrition/Pages/Switching-To-Solid-Foods.aspx (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Ministry of Health, New Zealand. Complementary Feeding (Solids) and Joining the Family Diet. In Food and Nutrition Guidelines for Healthy Infants and Toddlers (Aged 0–2): Background Paper; Public Health Commission: Wellington, New Zealand, 2008; pp. 22–36. ISBN 978-0-478-40238-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, New Zealand. New Zealand. New Zealand Food and Nutrition Guidelines. In Food and Nutrition Guidelines for Healthy Children and Young People (Aged 2–18 Years): Background Paper; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2015; pp. 6–13. ISBN 978-0-478-44483-4. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). A Modelling System to Inform the Revision of the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2011; pp. 40–67. ISBN 1864965398.

- Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Child and Adult Care Food Program: Meal Pattern Revisions Related to the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Final rule. Fed. Regist. 2016, 81, 24347–24383. Available online: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-01-15/pdf/2015-00446.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP). Manual Práctico de Nutrición en Pediatría; AEP: Madrid, Spain, 2007; ISBN 978-84-8473-594-6. Available online: https://www.aeped.es/sites/default/files/documentos/manual_nutricion.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Peña Quintana, L.; Ros Mar, L.; González Santana, D.M.; Rial González, R. Alimentación del preescolar y escolar. In Protocolos de Gastroenterología, Hepatología y Nutrición; Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP): Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 297–305. ISBN 978-84-8473-869-5. Available online: https://www.aeped.es/sites/default/files/documentos/3-alimentacion_escolar.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Manger Bouger & Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. Le guide de L’allaitement Maternel. Available online: http://www.mangerbouger.fr/content/download/3832/101789/version/3/file/1265.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Dalmau Serra, J.; Moreno Villares, J. Alimentación complementaria: Puesta al día. Pediatr. Integral 2017, 47, e1–e4. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrant, R.C.; Younger, K.M.; Sheridan-Pereira, M.; White, M.J.; Kearney, J.M. Factors associated with weaning practices in term infants: A prospective observational study in Ireland. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAndrew, F.; Thompson, J.; Fellows, L.; Large, A.; Speed, M.; Renfrew, M.J.; Renfrew, M.J. Infant Feeding Survey 2010; Health and Social Care Information Centre: Leeds, UK, 2012; Available online: https://sp.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/7281/mrdoc/pdf/7281_ifs-uk-2010_report.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2018).

- O’Donovan, S.M.; Murray, D.M.; Hourihane, J.O.; Kenny, L.C.; Irvine, A.D.; Kiely, M. Adherence with early infant feeding and complementary feeding guidelines in the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2864–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahlstrøm, S.; Knutsen, S.H. Oats and rye: Production and usage in Nordic and Baltic countries. Cereal Foods World 2010, 55, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaru, B.I.; Takkinen, H.M.; Niemelä, O.; Kaila, M.; Erkkola, M.; Ahonen, S.; Tuomi, H.; Haapala, A.M.; Kenward, M.G.; Pekkanen, J.; et al. Introduction of complementary foods in infancy and atopic sensitization at the age of 5 years: Timing and food diversity in a Finnish birth cohort. Allergy 2013, 68, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund-Blix, N.A.; Stene, L.C.; Rasmussen, T.; Torjesen, P.A.; Andersen, L.F.; Rønningen, K.S. Infant feeding in relation to islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in genetically susceptible children: The MIDIA Study. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AECOSAN. Consumo gramos/día (Base: Población Infantil de 12–35 meses). Available online: http://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/seguridad_alimentaria/evaluacion_riesgos/Consumo_12_36_meses.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Quann, E.; Carvalho, R. Starch consumption patterns in infants and young children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, S39–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friel, J.K.; Isaak, C.A.; Hanning, R.; Miller, A. Complementary food consumption of Canadian infants. Open Nutr. J. 2010, 3, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaahtera, M.; Kulmala, T.; Hietanen, A.; Ndekha, M.; Cullinan, T.; Salin, M.L.; Ashorn, P. Breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in rural Malawi. Acta Paediatr. 2001, 90, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimani-Murage, E.W.; Madise, N.J.; Fotso, J.-C.; Kyobutungi, C.; Mutua, M.K.; Gitau, T.M.; Yatich, N. Patterns and determinants of breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in urban informal settlements, Nairobi Kenya. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, J.; Emerson, J.A.; Amundson, K.; Doocy, S.; Caulfield, L.E.; Klemm, R.D.W. A qualitative analysis of barriers and facilitators to optimal breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Food Nutr. Bull. 2016, 37, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th ed.; Health and Human Services Dept. and Agriculture Dept.: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ (accessed on 13 July 2018).

- American Association of Cereal Chemists International (AACCI). Standard Definitions and Resources: Whole Grains. Available online: http://www.aaccnet.org/initiatives/definitions/Pages/WholeGrain.aspx (accessed on 6 July 2018).

- Liu, R.H. Whole grain phytochemicals and health. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 46, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truswell, A.S. Cereal grains and coronary heart disease. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Butts-Wilmsmeyer, C.J.; Mumm, R.H.; Rausch, K.D.; Kandhola, G.; Yana, N.A.; Happ, M.M.; Ostezan, A.; Wasmund, M.; Bohn, M.O. Changes in phenolic acid content in maize during food product processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 3378–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ktenioudaki, A.; Alvarez-Jubete, L.; Gallagher, E. A review of the process-induced changes in the phytochemical content of cereal grains: The breadmaking process. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adom, K.K.; Sorrells, M.E.; Liu, R.H. Phytochemicals and antioxidant activity of milled fractions of different wheat varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2297–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihlava, J.M.; Nordlund, E.; Heiniö, R.L.; Hietaniemi, V.; Lehtinen, P.; Poutanen, K. Phenolic compounds in wholegrain rye and its fractions. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 38, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žilić, S.; Serpen, A.; Akıllıoğlu, G.; Janković, M.; Gökmen, V. Distributions of phenolic compounds, yellow pigments and oxidative enzymes in wheat grains and their relation to antioxidant capacity of bran and debranned flour. J. Cereal Sci. 2012, 56, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Luthria, D.; Fuerst, E.P.; Kiszonas, A.M.; Yu, L.; Morris, C.F. Effect of processing on phenolic composition of dough and bread fractions made from refined and whole wheat flour of three wheat varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 10431–10436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kamp, J.W. Paving the way for innovation in enhancing the intake of whole grain. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 25, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anson, N.M.; Havenaar, R.; Bast, A.; Haenen, G.R. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacity of bioaccessible compounds from wheat fractions after gastrointestinal digestion. J. Cereal Sci. 2010, 51, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, Y.; Fulgoni, V.L. Grain foods are contributors of nutrient density for American adults and help close nutrient recommendation gaps: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009–2012. Nutrients 2017, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foschia, M.; Peressini, D.; Sensidoni, A.; Brennan, C.S. The effects of dietary fiber addition on the quality of common cereal products. J. Cereal Sci. 2013, 58, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.; Chater, P.I.; Wilcox, M.D.; Pearson, J.P.; Brownlee, I.A. The impact of dietary fibres on the physiological processes of the large intestine. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2018, 16, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1462. Available online: https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1462 (accessed on 8 November 2018).

- Commission Directive 2008/100/EC of 28 October 2008 amending Council Directive 90/496/EEC on nutrition labelling for foodstuffs as regards recommended daily allowances, energy conversion factors and definitions. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 285, 9–12.

- Slavin, J.; Tucker, M.; Harriman, C.; Jonnalagadda, S.S. Whole grains: Definition, dietary recommendations, and health benefits. Cereal Foods World 2013, 58, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, F.; Hareland, G.; Huseby, D. Soluble and insoluble dietary fiber content and composition in oat. Cereal Chem. 1999, 76, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.J. Impact of whole grains on the gut microbiota: The next frontier for oats? Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costabile, A.; Klinder, A.; Fava, F.; Napolitano, A.; Fogliano, V.; Leonard, C.; Gibson, G.R.; Tuohy, K.M. Whole-grain wheat breakfast cereal has a prebiotic effect on the human gut microbiota: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lappi, J.; Salojärvi, J.; Kolehmainen, M.; Mykkänen, H.; Poutanen, K.; de Vos, W.M.; Salonen, A. Intake of whole-grain and fiber-rich rye bread versus refined wheat bread does not differentiate intestinal microbiota composition in Finnish adults with metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanegas, S.M.; Meydani, M.; Barnett, J.B.; Goldin, B.; Kane, A.; Rasmussen, H.; Brown, C.; Vangay, P.; Knights, D.; Jonnalagadda, S.; et al. Substituting whole grains for refined grains in a 6-wk randomized trial has a modest effect on gut microbiota and immune and inflammatory markers of healthy adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vuholm, S.; Nielsen, D.S.; Iversen, K.N.; Suhr, J.; Westermann, P.; Krych, L.; Andersen, J.R.; Kristensen, M. Whole-grain rye and wheat affect some markers of gut health without altering the fecal microbiota in healthy overweight adults: A 6-week randomized trial. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 2067–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.; Teoh, K.T.; Savary, B.J.; Chen, M.H.; McClung, A.; Lee, S.O. In vitro fermentation patterns of rice bran components by human gut microbiota. Nutrients 2017, 12, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardet, A. New approaches to studying the potential health benefits of cereals: From reductionism to holism. Cereal Foods World 2014, 59, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutch Food Composition Database. NEVO-Online Version 2016/5.0. Available online: https://nevo-online.rivm.nl/ProductenZoeken.aspx (accessed on 7 September 2018).

- Thielecke, F.; Jonnalagadda, S.S. Can whole grain help in weight management? J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 48, S70–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertson, A.M.; Reicks, M.; Joshi, N.; Gugger, C.K. Whole grain consumption trends and associations with body weight measures in the United States: Results from the cross sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2012. Nutr. J. 2015, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roager, H.M.; Vogt, J.K.; Kristensen, M.; Hansen, L.B.S.; Ibrügger, S.; Mærkedahl, R.B.; Bahl, M.I.; Lind, M.V.; Nielsen, R.L.; Frøkær, H.; et al. Whole grain-rich diet reduces body weight and systemic low-grade inflammation without inducing major changes of the gut microbiome: A randomised cross-over trial. Gut 2017, 68, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Norat, T.; Romundstad, P.; Vatten, L.J. Whole grain and refined grain consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 28, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Hoffmann, G.; Lampousi, A.M.; Knüppel, S.; Iqbal, K.; Schwedhelm, C.; Bechthold, A.; Schlesinger, S.; Boeing, H. Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 32, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Pepa, G.; Vetrani, C.; Vitale, M.; Riccardi, G. Wholegrain intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: Evidence from epidemiological and intervention studies. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrø, C.; Tjønneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Olsen, A.; Landberg, R. Higher whole-grain intake is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes among middle-aged men and women: The Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Cohort. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1434–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malin, S.K.; Kullman, E.L.; Scelsi, A.R.; Haus, J.M.; Filion, J.; Pagadala, M.R.; Godin, J.P.; Kochhar, S.; Ross, A.B.; Kirwan, J.P. A whole-grain diet reduces peripheral insulin resistance and improves glucose kinetics in obese adults: A randomized-controlled trial. Metabolism 2018, 82, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Chan, D.S.; Lau, R.; Vieira, R.; Greenwood, D.C.; Kampman, E.; Norat, T. Dietary fiber, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2011, 343, d6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrø, C.; Olsen, A.; Landberg, R.; Skeie, G.; Loft, S.; Åman, P.; Leenders, M.; Dik, V.K.; Siersema, P.D.; Pischon, T.; et al. Plasma alkylresorcinols, biomarkers of whole-grain wheat and rye intake, and incidence of colorectal cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, djt352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Keum, N.; Giovannucci, E.; Fadnes, L.T.; Boffetta, P.; Greenwood, D.C.; Tonstad, S.; Vatten, L.J.; Riboli, E.; Norat, T. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2016, 353, i2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarem, N.; Nicholson, J.M.; Bandera, E.V.; McKeown, N.M.; Parekh, N. Consumption of whole grains and cereal fiber in relation to cancer risk: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, N.J. Fat, Sugar, Whole Grains and Heart Disease: 50 Years of Confusion. Nutrients 2018, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, N.F.; Frederiksen, K.; Christensen, J.; Skeie, G.; Lund, E.; Landberg, R.; Johansson, I.; Nilsson, L.M.; Halkjær, J.; Olsen, A.; et al. Whole-grain products and whole-grain types are associated with lower all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the Scandinavian HELGA cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zong, G.; Gao, A.; Hu, F.B.; Sun, Q. Whole grain intake and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Circulation 2016, 133, 2370–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benisi-Kohansal, S.; Saneei, P.; Salehi-Marzijarani, M.; Larijani, B.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Whole-grain intake and mortality from all Causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 1052–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, W.; Bao, W.; Wang, X. Association of whole grain intake with all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis from prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, C.; Walk, A.; Baumgartner, N.; Chojnacki, M.; Covello, A.; Evensen, J.; Thompson, S.; Holscher, H.; Khan, N. Relationship between whole grain consumption and selective attention: A behavioral and neuroelectric approach. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, A93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, R.C.; Liese, A.D.; Haffner, S.M.; Wagenknecht, L.E.; Hanley, A.J. Whole and refined grain intakes are related to inflammatory protein concentrations in human plasma. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitaglione, P.; Mennella, I.; Ferracane, R.; Rivellese, A.A.; Giacco, R.; Ercolini, D.; Gibbons, S.M.; La Storia, A.; Gilbert, J.A.; Jonnalagadda, S.; et al. Whole-grain wheat consumption reduces inflammation in a randomized controlled trial on overweight and obese subjects with unhealthy dietary and lifestyle behaviors: Role of polyphenols bound to cereal dietary fiber. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacco, R.; Costabile, G.; Della Pepa, G.; Anniballi, G.; Griffo, E.; Mangione, A.; Cipriano, P.; Viscovo, D.; Clemente, G.; Landberg, R.; et al. A whole-grain cereal-based diet lowers postprandial plasma insulin and triglyceride levels in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Metab. Cardiobasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marventano, S.; Vetrani, C.; Vitale, M.; Godos, J.; Riccardi, G.; Grosso, G. Whole grain intake and glycaemic control in healthy subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2017, 9, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, E.Q.; Chacko, S.A.; Chou, E.L.; Kugizaki, M.; Liu, S. Greater whole-grain intake is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and weight gain. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, D.N.; Kable, M.E.; Marco, M.L.; De Leon, A.; Rust, B.; Baker, J.E.; Horn, W.; Burnett, D.; Keim, N.L. The effects of moderate whole grain consumption on fasting glucose and lipids, gastrointestinal symptoms, and microbiota. Nutrients 2017, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langkamp-Henken, B.; Nieves, C., Jr.; Culpepper, T.; Radford, A.; Girard, S.A.; Hughes, C.; Christman, M.C.; Mai, V.; Dahl, W.J.; Boileau, T.; et al. Fecal lactic acid bacteria increased in adolescents randomized to whole-grain but not refined-grain foods, whereas inflammatory cytokine production decreased equally with both interventions. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 2025–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foerster, J.; Maskarinec, G.; Reichardt, N.; Tett, A.; Narbad, A.; Blaut, M.; Boeing, H. The influence of whole grain products and red meat on intestinal microbiota composition in normal weight adults: A randomized crossover intervention trial. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L.; Cao, W.; Chi, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, B. Whole cereal grains and potential health effects: Involvement of the gut microbiota. Food Res. Int. 2018, 103, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, S.A.; Hartley, L.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Jones, H.M.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Clar, C.; Germanò, R.; Lunn, H.R.; Frost, G.; et al. Whole grain cereals for the primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD005051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajihashemi, P.; Azadbakht, L.; Hashemipor, M.; Kelishadi, R.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Whole-grain intake favorably affects markers of systemic inflammation in obese children: A randomized controlled crossover clinical trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damsgaard, C.T.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Tetens, I.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Lind, M.V.; Astrup, A.; Landberg, R. Whole-grain intake, reflected by dietary records and biomarkers, is inversely associated with circulating insulin and other cardiometabolic markers in 8-to 11-year-old children. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, H.C.; Poh, B.K.; Abd Talib, R. The GReat-Child™ Trial: A quasi-experimental intervention on whole grains with healthy balanced diet to manage childhood obesity in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Nutrients 2018, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laitinen, T.T.; Nuotio, J.; Juonala, M.; Niinikoski, H.; Rovio, S.; Viikari, J.S.A.; Rönnemaa, T.; Magnussen, C.G.; Jokinen, E.; Lagström, H.; et al. Success in achieving the targets of the 20-year infancy-onset dietary intervention: Association with insulin sensitivity and serum lipids. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2236–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffei, H.V.; Vicentini, A.P. Prospective evaluation of dietary treatment in childhood constipation: High dietary fiber and wheat bran intake are associated with constipation amelioration. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2011, 52, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.L.; Schroeder, N.M. Dietary treatments for childhood constipation: Efficacy of dietary fiber and whole grains. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexy, U.; Zorn, C.; Kersting, M. Whole grain in children’s diet: Intake, food sources and trends. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellisle, F.; Hébel, P.; Colin, J.; Reyé, B.; Hopkins, S. Consumption of whole grains in French children, adolescents and adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1674–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mann, K.D.; Pearce, M.S.; McKevith, B.; Thielecke, F.; Seal, C.J. Whole grain intake and its association with intakes of other foods, nutrients and markers of health in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey rolling programme 2008–11. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1595–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neo, J.E.; Salleh, S.B.M.; Toh, Y.X.; How, K.Y.L.; Tee, M.; Mann, K.; Hopkins, S.; Thielecke, F.; Seal, C.J.; Brownlee, I.A. Whole-grain food consumption in Singaporean children aged 6–12 years. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welker, E.B.; Jacquier, E.F.; Catellier, D.J.; Anater, A.S.; Story, M.T. Room for improvement remains in food consumption patterns of young children aged 2–4 years. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, S1536–S1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielecke, F.; Nugent, A. Contaminants in grain—A major risk for whole grain safety? Nutrients 2018, 10, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznesof, S.; Brownlee, I.A.; Moore, C.; Richardson, D.P.; Jebb, S.A.; Seal, C.J. WHOLEheart study participant acceptance of wholegrain foods. Appetite 2012, 59, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMackin, E.; Dean, M.; Woodside, J.V.; McKinley, M.C. Whole grains and health: Attitudes to whole grains against a prevailing background of increased marketing and promotion. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, S.; Sánchez-Siles, L.M.; Siegrist, M. The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, M.; Evans, C.; Hugh-Jones, S. Factors influencing adolescent whole grain intake: A theory-based qualitative study. Appetite 2016, 101, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Magalis, R.M.; Giovanni, M.; Silliman, K. Whole grain foods: Is sensory liking related to knowledge, attitude, or intake? Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 46, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M.; Sheats, D.B. Consumer Trends in Grain Consumption. In Reference Module in Food Science; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-0-08-100596-5. Available online: http://scitechconnect.elsevier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Consumer-Trends-in-Grain-Consumption-1.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Nelson, M.E.; Hamm, M.W.; Hu, F.B.; Abrams, S.A.; Griffin, T.S. Alignment of healthy dietary patterns and environmental sustainability: A systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, S.; Sánchez-Siles, L.M. Parents’ choice criteria for infant food brands: A scale development and validation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Stategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health; World Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Information Council (EUFIC). Whole Grain Fact Sheet (Updated 2015). Available online: https://www.eufic.org/en/whats-in-food/article/whole-grains-updated-2015 (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Seal, C.J.; Nugent, A.P.; Tee, E.S.; Thielecke, F. Whole-grain dietary recommendations: The need for a unified global approach. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 2031–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Service (NHS). Starchy Foods and Carbohydrates. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/starchy-foods-and-carbohydrates/ (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Sociedad Española de Nutrición Comunitaria (SENC). Pirámide de la Alimentación Saludable. Available online: http://www.nutricioncomunitaria.org/es/noticia/piramide-de-la-alimentacion-saludable-senc-2015 (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Norwegian Nutrition Council (NNC). Dietary Guidelines to Improve Health and Prevent Chronic Diseases in the General Population. 2011. Available online: https://helsedirektoratet.no/publikasjoner/kostrad-for-a-fremme-folkehelsen-og-forebygge-kroniske-sykdommer-metodologi-og-vitenskapelig-kunnskapsgrunnlag (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Danish Veterinary and Food Administration (DVFA). The Danish Food Based Dietary Guidelines. 2012. Available online: https://altomkost.dk/raad-og-anbefalinger/de-officielle-kostraad/vaelg-fuldkorn/ (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Swedish National Food Agency (SNFA). Whole Grains. 2015. Available online: https://www.livsmedelsverket.se/globalassets/publikationsdatabas/rapporter/2015/rapp-hanteringsrapport-engelska-omslag--inlaga--bilagor-eng-version.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Brownlee, I.A.; Durukan, E.; Masset, G.; Hopkins, S.; Tee, E. An overview of whole grain regulations, recommendations and research across Southeast Asia. Nutrients 2018, 10, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varea Calderón, V.; Dalmau Serra, J.; Lama More, R.; Leis Trabazo, R. Papel de los cereales en la alimentación infantil. Acta Pediátr. Esp. 2013, 71, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Segura-Pérez, S.; Lott, M. Feeding guidelines for infants and young toddlers: A responsive parenting approach. Nutr. Today 2017, 52, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Heart Association (AHA). Dietary Recommendations for Healthy Children. 2016. Available online: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/Dietary-Recommendations-for-Healthy-Children_UCM_303886_Article.jsp#.W4-rbugza70 (accessed on 13 July 2018).

- Cereal Partners Worldwide (CPW). Consumers Confused about How Much Is Enough When It Comes to Whole Grain in Their Diets. 2017. Available online: https://www.nestle.com/asset-library/documents/media/news-feed/cpw-whole-grain-press-release-nov-2017.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2018).

- Gidding, S.S.; Dennison, B.A.; Birch, L.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Gilman, M.W.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Rattay, K.T.; Steinberger, J.; Stettler, N.; van Horn, L. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: A guide for practitioners. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whole Grains Council. Letter to the FDA on a Whole Grain Food Definition. 2014. Available online: https://wholegrainscouncil.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/WGCtoFDAJan2014.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2018).

- American Association of Cereal Chemists International (AACCI). AACCI’s Whole Grains Working Group Unveils New Whole Grain Products Characterization. 2013. Available online: http://www.aaccnet.org/about/newsreleases/pages/wholegrainproductcharacterization.aspx (accessed on 13 July 2018).

- Ferruzzi, M.G.; Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Liu, S.; Marquart, L.; McKeown, N.; Reicks, M.; Riccardi, G.; Seal, C.; Slavin, J.; Thielecke, F.; et al. Developing a standard definition of whole-grain foods for dietary recommendations: Summary report of a multidisciplinary expert roundtable discussion. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.B.; van der Kamp, J.-W.; King, R.; Lê, K.-A.; Mejborn, H.; Seal, C.J.; Thielecke, F. On behalf of the HEALTHGRAIN Forum. Perspective: A definition for whole-grain food products—Recommendations from the Healthgrain Forum. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Violette, C.; Kantor, M.A.; Ferguson, K.; Reicks, M.; Marquart, L.; Laus, M.J.; Cohen, N. Package information used by older adults to identify whole grain foods. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 35, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, T.Y.; Chien, Y.W.; Chang, J.S.; Chen, Y.C. Influence of mothers’ nutrition knowledge and attitudes on their purchase intention for infant cereal with no added sugar claim. Nutrients 2018, 10, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojsak, I.; Braegger, C.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; Colomb, V.; Decsi, T.; Domellöf, M.; Fewtrell, M.; Mis, N.F.; Mihatsch, W.; et al. Arsenic in rice: A cause for concern. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Inorganic Arsenic in Rice Cereals for Infants: Action Level Guidance for Industry. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/UCM493152.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/1006 of 25 June 2015 amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as regards maximum levels of inorganic arsenic in foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2015, 161, 14–16.

- Healthy Babies Bright Futures. Arsenic in 9 Brands of Infant Cereal: A National Survey of Arsenic Contamination in 105 Cereals from Leading Brands. Including Best Choices for Parents, Manufacturers and Retailers Seeking Healthy Options for Infants. Available online: http://www.healthybabycereals.org/sites/healthybabycereals.org/files/2017-12/HBBF_ArsenicInInfantCerealReport.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Alshannaq, A.; Yu, J.H. Occurrence, toxicity, and analysis of major mycotoxins in food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Flannery, B.M.; Oles, C.J.; Adeuya, A. Mycotoxins in infant/toddler foods and breakfast cereals in the US retail market. Food Addit. Contam. Part B Surveill. 2018, 11, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 364, 5–24.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific Opinion on acrylamide in food. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4104. Available online: https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4104 (accessed on 5 November 2018). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (FDA). Guidance for Industry Acrylamide in Foods. March 2016. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/ChemicalContaminantsMetalsNaturalToxinsPesticides/UCM374534.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2018).

- Seal, C.J.; de Mul, A.; Eisenbrand, G.; Haverkort, A.J.; Franke, K.; Lalljie, S.P.; Mykkänen, H.; Reimerdes, E.; Scholz, G.; Somoza, V.; et al. Risk-benefit considerations of mitigation measures on acrylamide content of foods—A case study on potatoes, cereals and coffee. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 9, S1–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Confederation of the European Food and Drink Industries (CIAA). Acrylamide Toolbox 2013. Available online: https://www.fooddrinkeurope.eu/uploads/publications_documents/AcrylamideToolbox_2013.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2158 of 20 November 2017 establishing mitigation measures and benchmark levels for the reduction of the presence of acrylamide in food. Off. J. Eur. Union 2017, 304, 24–44.

- Hadorn, B.; Zoppi, G.; Shmerling, D.H.; Prader, A.; McIntyre, I.; Anderson, C.M. Quantitative assessment of exocrine pancreatic function in infants and children. J. Pediatr. 1968, 73, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppi, G.; Andreotti, G.; Pajno-Ferrara, F.; Njai, D.M.; Gaburro, D. Exocrine pancreas function in premature and full term neonates. Pediatr. Res. 1972, 6, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilibridge, C.B.; Townes, P.L. Physiologic deficiency of pancreatic amylase in infancy: A factor in iatrogenic diarrhea. J. Pediatr. 1973, 82, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.H.M.; Nichols, B.L. The digestion of complementary feeding starches in the young child. Starch-Stärke 2017, 69, 1700012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auricchio, S.; Rubino, A.; Mürset, G. Intestinal glycosidase activities in the human embryo, fetus, and newborn. Pediatrics 1965, 35, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.C.; Werlin, S.; Trost, B.; Struve, M. Glucoamylase activity in infants and children: Normal values and relationship to symptoms and histological findings. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2004, 39, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.H.M.; Lee, B.H.; Nichols, B.L.; Quezada-Calvillo, R.; Rose, D.R.; Naim, H.Y.; Hamaker, B.R. Starch source influences dietary glucose generation at the mucosal α-glucosidase level. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 36917–36921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, M.T.; Edwards, C.A.; Preston, T.; Johnston, L.; Varley, R.; Weaver, L.T. Starch fermentation by faecal bacteria of infants, toddlers and adults: Importance for energy salvage. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 1486–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, M.; Edwards, C.; Weaver, L.T. Starch digestion in infancy. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1999, 29, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordain, L.; Eaton, S.B.; Sebastian, A.; Mann, N.; Lindeberg, S.; Watkins, B.A.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Brand-Miller, J. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: Health implications for the 21st century. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiniö, R.L.; Noort, M.W.J.; Katina, K.; Alam, S.A.; Sozer, N.; De Kock, H.L.; Hersleth, M.; Poutanen, K. Sensory characteristics of wholegrain and bran-rich cereal foods—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 47, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, J.E.; Brownlee, I.A. Wholegrain food acceptance in young Singaporean adults. Nutrients 2017, 9, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownlee, I.A.; Kuznesof, S.A.; Moore, C.; Jebb, S.A.; Seal, C.J. The impact of a 16-week dietary intervention with prescribed amounts of whole-grain foods on subsequent, elective whole grain consumption. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mellette, T.; Yerxa, K.; Therrien, M.; Camire, M.E. Whole grain muffin acceptance by young adults. Foods 2018, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.W.; Burgess Champoux, T.; Reicks, M.; Vickers, Z.; Marquart, L. White whole-wheat flour can be partially substituted for refined-wheat flour in pizza crust in school meals without affecting consumption. J. Child Nutr. Manag. 2008, 32. Available online: http://schoolnutrition.org/5--news-and-publications/4--the-journal-of-child-nutrition-and-management/spring-2008/volume-32,-issue-1,-spring-2008---chan;-burgess-champoux;-reicks;-vickers;-marquart/ (accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Rosen, R.A.; Sadeghi, L.; Schroeder, N.; Reicks, M.M.; Marquart, L. Gradual incorporation of whole wheat flour into bread products for elementary school children improves whole grain intake. J. Child Nutr. Manag. 2008, 32. Available online: https://schoolnutrition.org/5--News-and-Publications/4--The-Journal-of-Child-Nutrition-and-Management/Fall-2008/Volume-32,-Issue-2,-Fall-2008---Rosen;-Sadeghi;-Schroeder;-Reicks;-Marquart/ (accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Toma, A.; Omary, M.B.; Marquart, L.F.; Arndt, E.A.; Rosentrater, K.A.; Burns-Whitmore, B.; Kessler, L.; Hwan, K.; Sandoval, A.; Sung, A. Children’s acceptance, nutritional, and instrumental evaluations of whole grain and soluble fiber enriched foods. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haro-Vicente, J.F.; Bernal-Cava, M.J.; Lopez-Fernandez, A.; Ros-Berruezo, G.; Bodenstab, S.; Sánchez-Siles, L.M. Sensory acceptability of infant cereals with whole grain in infants and young children. Nutrients 2017, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cosmi, V.; Scaglioni, S.; Agostoni, C. Early taste experiences and later food choices. Nutrients 2017, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennella, J.A.; Bobowski, N.K. The sweetness and bitterness of childhood: Insights from basic research on taste preferences. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heiniö, R.L.; Liukkonen, K.H.; Myllymäki, O.; Pihlava, J.M.; Adlercreutz, H.; Heinonen, S.M.; Poutanen, K. Quantities of phenolic compounds and their impacts on the perceived flavour attributes of rye grain. J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 47, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, Q.; Peterson, D.G. Identification of bitter compounds in whole wheat bread crumb. Food Chem. 2016, 203, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, G.; Coulthard, H. Early eating behaviors and food acceptance revisited: Breastfeeding and introduction of complementary foods as predictive of food acceptance. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2016, 5, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicklaus, S. Relationships between early flavor exposure, and food acceptability and neophobia. In Flavor: From Food to Behaviors, Wellbeing and Health; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 293–311. ISBN 978-0-08-100300-8. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Maier-Nöth, A.; Schaal, B.; Leathwood, P.; Issanchou, S. The lasting influences of early food-related variety experience: A longitudinal study of vegetable acceptance from 5 months to 6 years in two populations. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, R.D. Savoring sweet: Sugars in infant and toddler feeding. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 70, S38–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicklaus, S. The role of food experiences during early childhood in food pleasure learning. Appetite 2016, 104, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekitsing, C.; Hetherington, M.M.; Blundell-Birtill, P. Developing healthy food preferences in preschool children through taste exposure, sensory learning, and nutrition education. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2018, 7, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, A.S.; Wang, P.; Wang, N.; Yang, S.; Xiao, Z. Technologies for enhancement of bioactive components and potential health benefits of cereal and cereal-based foods: Research advances and application challenges. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 28, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country/Region and Organization | Wording, Recommendation or Guideline |

|---|---|

| Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) [27] | Infant cereals, dry, mixed grain, fortified Six to 12 months: seven serves per week, one serve weighs 20 g |

| Europe: European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) [22] | “It should be noted that for formula-fed infants and some breast-fed infants after four to six months of age, an intake equivalent to this value (0.3 mg per day iron from breast milk) is not sufficient to maintain iron status within the normal range”. |

| Europe: Domellöf et al.; Fewtrell et al. (on behalf of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, or ESPGHAN) [15,21] | “There may be some beneficial effects on iron stores of introducing complementary food alongside breast-feeding from four months. Iron-rich complementary foods are recommended, these include iron-fortified foods such as cereals. Gluten may be introduced between four and 12 months”. |

| France: Manger Bouger & Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé [31] | 0–4 months: no cereal intake |

| 5–6 months: cereals without gluten | |

| >7 months: cereals with gluten | |

| New Zealand: Ministry of Health [25,26] | 0–6 months: no cereal intake 6–7 months: iron-fortified cereals, puréed plain rice 7–8 months: age-appropriate infant cereals 8–12 months: breakfast cereals such as porridge, wheat biscuits (iron-fortified), infant muesli 12–24 months: all previously listed cereals 2–5 years: “At least four servings of cereals per day. Increasing whole grain options as children age”. |

| Spain: Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP) [29]; Peña Quintana et al. (AEP) [30]; Dalmau Serra & Moreno Villares (AEP) [32] | < 5–6 months: cereals without gluten > 5–6 months: cereals with gluten 12 months: 57 g of cereals per day 24–36 months: 86 g of cereals per day “Fortified or whole grain (preferred) cereals, bread and pastas are suggested”. |

| US: American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) [23,24] | “A baby’s digestive system is not thought to be well prepared to process cereals until about six months of age. When he is old enough to digest cereal, he should also be ready to eat it from a spoon”. “Baby cereals are available premixed in individual containers or dry, to which you can add breast milk, formula, or water. Whichever type of cereal you use, make sure that it is made for babies and iron fortified”. |

| US: Food and Nutrition Service, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) [28] | Breakfast, lunch, supper, or snack 6–11 months: 0–4 tablespoons of iron-fortified infant cereals or iron-fortified ready-to-eat breakfast cereals (in case of a snack) “A serving of this component is required when the infant is developmentally ready to accept it. A serving of grains must be whole grain rich, enriched meal, or enriched flour. Breakfast cereals must contain no more than 6 g of sugar per dry ounce (no more than 21 g sucrose and other sugars per 100 g of dry cereal)”. |

| Nutrient | Whole Wheat Flour | Refined Wheat Flour (75% Extraction) |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates, g (% of energy) | 62 (75.6) | 71 (80.6) |

| Protein, g (% of energy) | 10 (12.2) | 12.6 (14.3) |

| Fat, g (% of energy) | 2 (5.5) | 1.1 (2.8) |

| Dietary fiber, g | 11 | 4 |

| Vitamin B1, mg | 0.4 | 0.07 |

| Vitamin B2, mg | 0.15 | 0.04 |

| Vitamin B3, mg | 5.7 | 1 |

| Vitamin B6, mg | 0.35 | 0.12 |

| Vitamin B9, mg | 0.037 | 0.022 |

| Vitamin E, mg | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| Vitamin K, mg | 0.019 | 0.008 |

| Iron, mg | 4 | 0.8 |

| Zinc, mg | 2.9 | 0.64 |

| Magnesium, mg | 124 | 20 |

| Sodium, mg | 5 | 2 |

| Potassium, mg | 250 | 156 |

| Phosphorus, mg | 370 | 103 |

| Country/Region and Organization | Wording, Recommendation, or Guideline |

|---|---|

| Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) [27] | 13–23 months: - Whole grain or higher fiber cereals/grains: 16 serves * per week - Refined or lower fiber cereals/grains **: 8.5 serves * per week 24–36 months: - Whole grain or higher fiber cereals/grains: 19 serves * per week - Refined or lower fiber cereals/grains **: Nine serves * per week |

| Spain: Varea Calderón et al. [129] | <24 months: “It is necessary to consume four to six servings of cereals per day to meet the dietary requirements; moreover, half of these servings should be whole grain to meet the fiber requirements”. |

| US: American Academy Pediatrics (AAP) [23,24]; American Heart Association (AHA) [131] and Gidding et al. [133] | 12 months: - Two ounces of cereals per day - Make sure half of the amount is whole grain 12–24 months: - Three ounces of cereals per day - Make sure half of the amount is whole grain “Serve whole grain breads and cereals rather than refined grain products. Look for whole grain as the first ingredient on the food label”. |

| US: Food and Nutrition Service, US Department of Agriculture (USDA) [28] | “At least one serving per day, across all eating occasions, must be whole grain or whole grain-rich. Grain-based desserts do not count towards meeting the grains requirement”. 12–24 months: Breakfast (minimum amount to be served) - ½ slice of whole grain-rich or enriched bread or; - ½ serving of whole grain-rich or enriched bread product, such as biscuit, roll, or muffin, or; - ¼ cup of whole grain-rich, enriched, or fortified cooked breakfast cereal, cereal grain, and/or pasta Lunch and supper (minimum amount to be served) - ½ slice of whole grain-rich or enriched bread or; - ½ serving of whole grain-rich or enriched bread product, such as biscuit, roll, or muffin or; - ¼ cup of whole grain-rich, enriched, or fortified cereal, cereal grain, and/or pasta Optional best practices that providers may choose to implement to make further nutritional improvements to the meals they serve: “The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended that at least half of all grains served are whole grain-rich. To meet this goal, providers are encouraged to prepare at least two servings of whole grain-rich grains each day. This is an increase from the required one serving of whole grain-rich grains per day”. |

| US: Healthy Eating Research, Pérez-Escamilla et al. [130] | Six to 12 months: “What your baby eats at around nine months is indicative of what she/he will like to eat when school-aged. Offer your baby a variety of vegetables and fruits and whole grain products (e.g., brown rice, whole grain cereals)”. 12–24 months: “Offer your toddler whole grain food, such as whole wheat bread, whole wheat pasta, maize tortillas, or brown rice. These food items are rich in fiber, which is often missing from children’s diets. Offer ½ to one slice of whole grain bread, or ¼ to ½ cup of whole grain cereal or pasta at most meals and snacks”. |

| US: US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and US Department of Agriculture (USDA) [45] | 12–36 months: - Whole grain: 1.5 to 2.5-ounce equivalents *** or above - At least half of total grain consumption is whole grain |

| Author, Year | Country | Age | Main Results |

| Brownlee et al. 2013 [164] | UK | +18 years | “Whole grain consumption was significantly higher in participants who were provided with whole grain foods throughout the intervention period compared with the control group that was not provided with whole grain foods (approximately doubled, p < 0.001) and compared to baseline”. |

| Chan et al. 2008 [166] | US | 6–11 years | “There was no difference in children’s consumption of the 50:50 blend pizza (50% whole grain and 50% refined grain) compared to the 100% refined counterpart (mean consumption 106 ± 4 g of 50:50 pizza compared to 100 ± 2 g of refined pizza)”. |

| Haro-Vicente et al. 2017 [169] | Spain | 4–24 months | “Overall acceptability for infant cereals with whole grain and refined cereals was very similar both for infants (2.30 ± 0.12 and 2.32 ± 0.11, p = 0.606) and parents (6.1 ± 0.8 and 6.0 ± 0.9, p = 0.494). Sensory evaluation of the color, aroma, taste, and texture by parents indicated no significant difference between both types of infant cereals (all p > 0.05)”. |

| Kuznesof et al. 2012 [112] | UK | 18–65 years | “Many participants expressed surprise at liking the taste of whole grain foods that they had either prejudged to be ‘tasteless’ or recalled (on the basis of a previous eating experience) to taste inferior to alternatives. A preference for certain whole grain foods was established over time”. |

| Magalis et al. 2016 [116] | UK | 18–19 years | “Both refined rice and refined pasta were significantly more well-liked than their whole grain counterparts for all sensory attributes (p ≤ 0.05). For tortillas and bread, the whole wheat and refined wheat samples were similarly well-liked (p > 0.05)”. |

| Mellette et al. 2018 [165] | US | 18–24 years | “Respondents liked all muffin formulations (muffins containing 50%, 75%, and 100% whole wheat flour) similarly for appearance, taste, texture, and overall liking. After the whole grain content of each muffin was revealed, 66% of students increased their liking of the muffin containing 100% whole wheat flour”. |

| Neo and Brownlee, 2017 [163] | Singapore | 21–26 years | “The whole grain familiarization period did not alter the taste expectations of the consumers, but it did manage to increase acceptance for four of the whole grain products tested (p < 0.001 for oatmeal cookie, granola bar, and muesli, p < 0.05 for wheat biscuit breakfast cereal”. |

| Rosen et al. 2008 [167] | US | Kindergarten–6th grade children | “Mean consumption of buns and rolls at the baseline for both schools (0% whole wheat) was ~75%. Intake of bread products did not differ significantly from the baseline level up to the 59% level of red whole wheat and 45% of the white whole wheat. The range of consumption for dinner rolls made with red whole wheat flour was 57% to 77%, while white whole wheat flour was 50% to 78%, indicating that grain bread products may be more acceptable, with a total whole grain flour content approaching 75%”. |

| Toma et al. 2009 [168] | US | Kindergarten–6th grade children | “No significant differences (p > 0.05) in consumption between control products (products with refined flour) and test products (burritos and cookies containing 51% and 100% whole grain, respectively) were found”. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klerks, M.; Bernal, M.J.; Roman, S.; Bodenstab, S.; Gil, A.; Sanchez-Siles, L.M. Infant Cereals: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Opportunities for Whole Grains. Nutrients 2019, 11, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020473

Klerks M, Bernal MJ, Roman S, Bodenstab S, Gil A, Sanchez-Siles LM. Infant Cereals: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Opportunities for Whole Grains. Nutrients. 2019; 11(2):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020473

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlerks, Michelle, Maria Jose Bernal, Sergio Roman, Stefan Bodenstab, Angel Gil, and Luis Manuel Sanchez-Siles. 2019. "Infant Cereals: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Opportunities for Whole Grains" Nutrients 11, no. 2: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020473

APA StyleKlerks, M., Bernal, M. J., Roman, S., Bodenstab, S., Gil, A., & Sanchez-Siles, L. M. (2019). Infant Cereals: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Opportunities for Whole Grains. Nutrients, 11(2), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020473