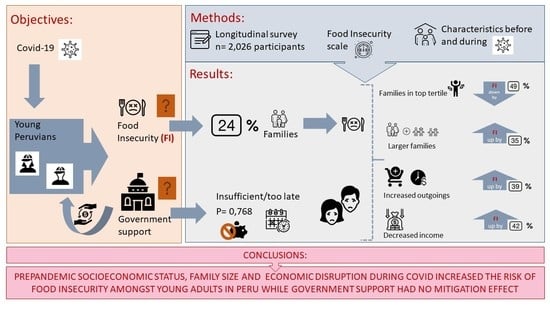

Role of Government Financial Support and Vulnerability Characteristics Associated with Food Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Young Peruvians

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Food Insecurity

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Household Characteristics Associated with Food Insecurity Status

3.2. Role of the Government Support and Vulnerability Characteristics Associated with Food Insecurity

4. Discussion

Limitation and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johns Hopkins University of Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Center: Mortality Analyses. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Varona, L.; Gonzales, J.R. Dynamics of the impact of COVID-19 on the economic activity of Peru. PLoS ONE 2021, 8, e0244920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundial, B. Crisis por el Coronavirus Aumentó las Desigualdades en el Perú: Comunicado de Prensa N.o08.09.2020; Banco Mundial: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Banco Central de Reserva del Perú. Reporte de Inflación: Panorama Actual y Proyecciones Macroeconómicas 2020–2022. Perú. 2020. Available online: https://www.bcrp.gob.pe/docs/Publicaciones/Reporte-Inflacion/2020/diciembre/reporte-de-inflacion-diciembre-2020.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Pobreza Monetaria Alcanzó al 20.2% de la Población en el año 2019. INEI. 2020. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/prensa/noticias/pobreza-monetaria-alcanzo-al-202-de-la-poblacion-en-el-ano-2019-12196/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional en América Latina y el Caribe-División de Desarrollo Social CEPAL. Available online: https://dds.cepal.org/san/marco-conceptual (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI) Principales Efectos Del covid-19 en Los Hogares de Lima Metropolitana y Callao. Presentado en Conferencia. 2020. Available online: https://www.comuniteca.org/uploads/libros/6d7479ae10ce00402e7d29fc87ae798804347dce.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- COVID-19 Cambios en Preferencias y Hábitos de Consumo en Hogares Peruanos. KANTAR. 2020. Available online: https://andaperu.pe/kantar-covid-19-cambia-preferencias-y-habitos-de-consumo-en-hogares-peruanos/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- UNICEF. La COVID-19 ha Generado Mayor Pobreza y Desigualdad en la Niñez y Adolescencia. 2020. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/peru/comunicados-prensa/la-covid-19-ha-generado-mayor-pobreza-y-desigualdad-en-la-niñez-y-adolescencia-Banco-mundial (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Conoce Cómo Cobrar el Bono Familiar Universal–BFU. Plataforma Digital Gobierno del Perú. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/10979-conoce-como-cobrar-el-bono-familiar-universal-bfu (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, F. Impact of Cash Transfer on Food Security: A Review. Nutr. Food Sci. Res. 2016, 3, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrega de Bonos a Hogares en el Contexto de la Emergencia por la COVID-19: Dificultades y Recomendaciones. Defensoria del Pueblo. Lima. 2020. Available online: https://www.defensoria.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Serie-Informes-Especiales-N%C2%BA-25-2020-DP-Entrega-de-bonos-a-hogares-en-el-contexto-de-la-emergencia-por-la-COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. Bono Familiar Universal: ¿Cuáles son los Problemas de Fondo de Identificar a los Beneficiarios del Subsidio. Available online: https://iep.org.pe/noticias/analisis-bono-familiar-universal-cuales-son-los-problemas-de-fondo-de-identificar-a-los-beneficiarios-del-subsidio/ (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Pillaca-Medina, S.; Chavez-Dulanto, P.N. How effective and efficient are social programs on food and nutritional security? Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 00120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobal, J.; Flores, E. An Assessment of the Young Lives Sampling Approach in Peru. Technical Note N° 3. Oxford: Young Lives. 2008. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=es&user=tsU9VsAAAAAJ&citation_for_view=tsU9VsAAAAAJ:u-x6o8ySG0sC (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Briones, K. How Many Rooms are There in Your House? Constructing the Young Lives Wealth Index. 2017. Available online: http://doc.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/8357/mrdoc/pdf/8357_yl-tn43_0.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Cafiero, C.; Viviani, S.; Nord, M. Food security measurement in a global context: The food insecurity experience scale. Measurement 2018, 116, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E-learning Course: SDG Indicator 2.1.2-Using the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES)|Knowledge Hub. Available online: https://knowledge.unccd.int/cbm/e-learning-course-sdg-indicator-212-using-food-insecurity-experience-scale-fies (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Bulawayo, M.; Ndulo, M.; Sichone, J. Socioeconomic Determinants of Food Insecurity among Zambian Households: Evidence from a National Household Survey. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2019, 54, 800–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, K.; Murray, S.; Penrose, B.; Auckland, S.; Visentin, D.; Godrich, S.; Lester, E. Prevalence and Socio-Demographic Predictors of Food Insecurity in Australia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Kassa, W.; Winters, P. Assessing food insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean using FAO’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale. Food Policy 2017, 71, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ihab, A.; Rohana, A.; Manan, W.W.; Suriati, W.W.; Zalilah, M.; Rusli, A.M. Nutritional Outcomes Related to Household Food Insecurity among Mothers in Rural Malaysia. J. Heal Popul. Nutr. 2014, 31, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gozzer Infante, E. Salud Rural en Latinoamérica en Tiempos de COVID-19. Available online: https://repositorio.iep.org.pe/handle/IEP/1181 (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Batis, C.; Mazariegos, M.; Martorell, R.; Gil, A.; A Rivera, J. Malnutrition in all its forms by wealth, education and ethnicity in Latin America: Who are more affected? Public Heal Nutr. 2020, 23, s1–s12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curi-Quinto, K.; Ortiz-Panozo, E.; De Romaña, D.L. Malnutrition in all its forms and socio-economic disparities in children under 5 years of age and women of reproductive age in Peru. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23 (Suppl. 1), S89–S100.25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Programas Sociales y de Subsidios del Estado que Emplean la Clasificación Socioeconómica (CSE). Available online: http://www.sisfoh.gob.pe/ciudadania/que-es-la-clasificacion-socioeconomica-cse/programas-sociales-y-de-subsidios-del-estado-que-emplean-la-clasificacion-socioeconomica-cse (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Coronavirus: What’s Happening in Peru?-BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-53150808 (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Handbook for Defining and Setting up a Food Security Information and Early Warning System (FSIEWS). Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/X8622E/x8622e04.htm (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Hart, T.G. Exploring definitions of food insecurity and vulnerability: Time to refocus assessments. Agrekon 2009, 48, 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomati, M.; Mendoza-Quispe, D.; Anza-Ramirez, C.; Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Larco, R.M.C.; Fernandez, G.; Nandy, S.; Miranda, J.J.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A. Trends and patterns of the double burden of malnutrition (DBM) in Peru: A pooled analysis of 129,159 mother–child dyads. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.P.; Turner, B.; Chaparro, M.P. The double burden of malnutrition in Peru: An update with a focus on social inequities. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centro Nacional de Planeamiento Estratégico (CEPLAN). Peru 2050: Tendencias Nacionales con el Impacto del COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.ceplan.gob.pe/documentos_/peru-2050-tendencias-nacionales-con-impacto-de-la-covid-19/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Canari-Casano, J.L.; Elorreaga, O.A.; Cochachin-Henostroza, O.; Huaman-Gil, S.; Dolores-Maldonado, G.; Aquino-Ramirez, A.; Giribaldi-Sierralta, J.P.; Aparco, J.P.; Antiporta, D.A.; Penny, M.E. Social predictors of food insecurity during the stay-at-home order due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru. Results from a cross-sectional web-based survey. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorell, R.; Young, M.F. Patterns of Stunting and Wasting: Potential Explanatory Factors. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reinhard, I.; Wijayaratne, K. The Use of Stunting and Wasting as Indicators for Food Insecurity and Poverty; Working Paper; Integrated Food Security Program; PIMU Open Forum: Trincomalee, Sri Lanka, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, D.L.; Dearden, K.A.; Crookston, B.T.; Fernald, L.C.; Stein, A.D.; Woldehanna, T.; Penny, M.E.; Behrman, J.R.; The Young Lives Determinants and Consequences of Child Growth Project Team. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Associations between Household Food Security and Child Anthropometry at Ages 5 and 8 Years in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1924–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- MIDIS. El 73% de los Comedores Populares del Ámbito del Programa de Complementación Alimentaria se ha Reactivado en Todo el país|Gobierno del Perú. 2020. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/midis/noticias/304643-midis-el-73-de-los-comedores-populares-del-ambito-del-programa-de-complementacion-alimentaria-se-ha-reactivado-en-todo-el-pais (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Díaz-Garcés, F.A.; Vargas-Matos, I.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A.; Diez-Canseco, F.; Trujillo, A.J.; Miranda, J.J. Factors associated with consumption of fruits and vegetables among Community Kitchens customers in Lima, Peru. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corvalán, C.; Garmendia, M.L.; Jones-Smith, J.; Lutter, C.K.; Miranda, J.J.; Pedraza, L.S.; Popkin, B.M.; Ramirez-Zea, M.; Salvo, D.; Stein, A.D. Nutrition status of children in Latin America. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Roman, J.S.; Azañedo, D.; Ruiz, E.F.; Avilez, J.L.; Málaga, G. The double burden of malnutrition: A threat for Peruvian childhood. Gac. Sanit. 2017, 31, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossio-Bolaños, M.; Campos, R.G.; Andruske, C.L.; Flores, A.V.; Luarte-Rocha, C.; Olivares, P.R.; Garcia-Rubio, J.; De Arruda, M. Physical Growth, Biological Age, and Nutritional Transitions of Adolescents Living at Moderate Altitudes in Peru. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2015, 12, 12082–12094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Correia, L.L.; Rocha, H.A.L.; Leite, Á.J.M.; e Silva, A.C.; Campos, J.S.; Machado, M.M.T.; Lindsay, A.C.; da Cunha, A.J.L.A. The of cash transfer programs and food insecurity among families with preschool children living in semiarid climates in Brazil. Cad. Saúde Colet. 2018, 26, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Moderate and Severe FI (FIES ≥ 4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | Overall (n) | No (%) | Yes (%) | p-Value χ2 | |

| 1975 | 76.00 | 24.00 | |||

| Sex of the YLS participant | |||||

| Male | 1002 | 77.84 | 22.16 | 0.051 | |

| Female | 973 | 74.10 | 25.90 | ||

| Type of cohort | 0.348 | ||||

| Young Cohort (18–19 years) | 1523 | 75.51 | 24.49 | ||

| Older Cohort (24–27 years) | 452 | 77.65 | 22.35 | ||

| Mother Education | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 199 | 64.82 | 35.18 | ||

| Primary education | 718 | 74.23 | 25.77* | ||

| Above Primary | 1014 | 79.78 | 20.22 *† | ||

| Ethnicity (Mother´s language) | <0.001 | ||||

| Any Andean/native language | 559 | 70.13 | 29.87 | ||

| Spanish | 1385 | 78.56 | 21.44 | ||

| Family size | |||||

| Less or equal to 5 members | 1319 | 78.62 | 21.38 | <0.001 | |

| More than 5 members | 656 | 70.73 | 29.27 | ||

| Family composition | |||||

| Family with any children under 5 years. | 739 | 72.94 | 27.06 | 0.014 | |

| Family without children under 5 years. | 1236 | 77.83 | 22.17 | ||

| Family with any older adult (>65 years) | 509 | 79.37 | 20.63 | 0.039 | |

| Family without older adult (>65 years) | 1406 | 74.83 | 25.17 | ||

| Previous chronic pathology, mental or physical disability | |||||

| With pathology | 118 | 73.73 | 26.27 | 0.551 | |

| Without pathology | 1857 | 76.14 | 23.86 | ||

| History of malnutrition | |||||

| Stunting/short stature (8–12 and 15 years) | 183 | 63.93 | 36.07 | <0.001 | |

| Non-Stunting | 1792 | 77.23 | 22.77 | ||

| Overweight | 569 | 76.98 | 23.02 | 0.509 | |

| Non-Overweight | 1392 | 75.57 | 24.43 | ||

| Moderate and Severe Food Insecurity (FIES ≥ 4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n) | No (%) | Yes (%) | p-value χ2 | |

| Area of residence | ||||

| Urban | 1625 | 77.35 | 22.65 | 0.002 |

| Rural | 350 | 69.71 | 30.29 | |

| Region of residence | 0.020 | |||

| Coast | 940 | 78.62 | 21.38 | |

| Highland | 748 | 74.47 | 25.53 | |

| Jungle | 287 | 71.43 | 28.57 * | |

| Wealth Index | <0.001 | |||

| Bottom tercile | 618 | 68.28 | 31.72 | |

| Middle tercile | 638 | 76.02 | 23.98 * | |

| Top tercile | 702 | 82.91 | 17.09 † | |

| Self-reported changes due to COVID-19 | ||||

| Increase in household expenses | 1285 | 73.46 | 26.54 | <0.001 |

| Decrease in household income | 1511 | 73.79 | 26.21 | <0.001 |

| Any member of the family with COVID-19 | 263 | 76.43 | 23.57 | 0.887 |

| Unemployed due to COVID-19 | 634 | 75.00 | 25.00 | 0.001 |

| Received assistance from friends/relative during COVID-19 | 370 | 62.16 | 37.84 | <0.001 |

| Job Sector of the YLS participants during COVID-19 | ||||

| No work | 373 | 83.11 | 16.89 | 0.001 |

| Agriculture, livestock, and forestry | 371 | 69.54 | 30.46 * | |

| Financial activities and accommodation | 233 | 78.11 | 21.89 | |

| Construction and mining | 194 | 71.65 | 28.35 * | |

| Trade | 340 | 75.88 | 24.12 | |

| Other services | 202 | 78.22 | 21.78 | |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI 95% | p-Value | OR | CI 95% | p-Value | OR | CI 95% | p-Value | |

| The family received “Bonos” during COVID-19 | 1.00 | 0.80–1.26 | 0.971 | 1.00 | 0.80–1.25 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.77–1.27 | 0.768 |

| Recipient of any existing social program before COVID-19 | 0.77 | 0.53–1.13 | 0.177 | 0.78 | 0.53–1.15 | 0.216 | 0.77 | 0.52–1.13 | 0.181 |

| Longer period of lockdown (>199 days) | (...) | (...) | 0.91 | 066–1.25 | 0.559 | 0.93 | 0.67–1.29 | 0.656 | |

| Household vulnerability characteristics | |||||||||

| Area of residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 1.12 | 0.82–1.55 | 0.479 | 1.12 | 0.81–1.54 | 0.484 | 1.15 | 0.83–1.59 | 0.401 |

| Region of residence | |||||||||

| Mountain | 0.91 | 0.70–1.18 | 0.478 | 0.91 | 0.70–1.19 | 0.494 | 0.91 | 0.69–1.19 | 0.485 |

| Jungle | 1.13 | 0.79–1.59 | 0.506 | 1.16 | 0.81–1.67 | 0.423 | 1.15 | 0.80–1.65 | 0.463 |

| Wealth Index | |||||||||

| Middle tercile | 0.75 | 0.56–1.01 | 0.058 | 0.75 | 0.56–1.01 | 0.058 | 0.73 * | 0.54–0.98 | 0.035 |

| Top tercile | 0.50 * | 0.36–0.69 | <0.001 | 0.50 * | 0.36–0.70 | <0.001 | 0.51 * | 0.37–0.70 | <0.001 |

| Household size: more than five members | 1.42 * | 1.12–1.80 | 0.004 | 1.41 * | 1.12–1.79 | 0.004 | 1.35 * | 1.07–1.72 | 0.013 |

| Presence of child under 5 years | 1.16 | 0.92–1.46 | 0.215 | 1.16 | 0.92–1.46 | 0.216 | 1.15 | 0.91–1.45 | 0.244 |

| Mother Education level | |||||||||

| Primary education | 0.76 | 0.53–1.10 | 0.151 | 0.77 | 0.53–1.12 | 0.172 | 0.76 | 0.53–1.11 | 0.157 |

| Above Primary | 0.72 | 0.48–1.09 | 0.120 | 0.74 | 0.49–1.11 | 0.147 | 0.73 | 0.48–1.10 | 0.134 |

| Ethnicity: Indigenous | 1.23 | 0.93–1.64 | 0.150 | 1.25 | 0.94–1.67 | 0.128 | 1.20 | 0.89–1.61 | 0.226 |

| Type of cohort: Younger cohort (18–19 years) | 1.12 | 0.85–1.46 | 0.440 | 1.11 | 0.84–1.45 | 0.462 | 1.12 | 0.85–1.47 | 0.428 |

| Self-reported changes due to COVID-19 | |||||||||

| Increased household expenses | (...) | (...) | (...) | (...) | 1.39 * | 1.09–1.77 | 0.008 | ||

| Decreased household income | (...) | (...) | (...) | (...) | 1.42 * | 1.06–1.90 | 0.018 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Curi-Quinto, K.; Sánchez, A.; Lago-Berrocal, N.; Penny, M.E.; Murray, C.; Nunes, R.; Favara, M.; Wijeyesekera, A.; Lovegrove, J.A.; Soto-Cáceres, V.; et al. Role of Government Financial Support and Vulnerability Characteristics Associated with Food Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Young Peruvians. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3546. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103546

Curi-Quinto K, Sánchez A, Lago-Berrocal N, Penny ME, Murray C, Nunes R, Favara M, Wijeyesekera A, Lovegrove JA, Soto-Cáceres V, et al. Role of Government Financial Support and Vulnerability Characteristics Associated with Food Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Young Peruvians. Nutrients. 2021; 13(10):3546. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103546

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuri-Quinto, Katherine, Alan Sánchez, Nataly Lago-Berrocal, Mary E. Penny, Claudia Murray, Richard Nunes, Marta Favara, Anisha Wijeyesekera, Julie A. Lovegrove, Victor Soto-Cáceres, and et al. 2021. "Role of Government Financial Support and Vulnerability Characteristics Associated with Food Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Young Peruvians" Nutrients 13, no. 10: 3546. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103546

APA StyleCuri-Quinto, K., Sánchez, A., Lago-Berrocal, N., Penny, M. E., Murray, C., Nunes, R., Favara, M., Wijeyesekera, A., Lovegrove, J. A., Soto-Cáceres, V., & Vimaleswaran, K. S. (2021). Role of Government Financial Support and Vulnerability Characteristics Associated with Food Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Young Peruvians. Nutrients, 13(10), 3546. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103546