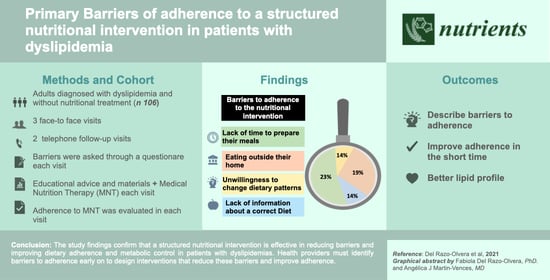

Primary Barriers of Adherence to a Structured Nutritional Intervention in Patients with Dyslipidemia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Barriers

3.2. Adherence and Dietary Patterns

3.3. Metabolic Control/Lipid Profile Changes

4. Discussion

4.1. Barriers to Adherence

4.2. Adherence

4.3. Metabolic Control/Lipid Profile Changes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mc Namara, K.; Alzubaidi, H.; Jackson, J.K. Cardiovascular disease as a leading cause of death: How are pharmacists getting involved? Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2019, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Foreman, K.; Lim, S.; Shibuya, K.; Aboyans, V.; Abraham, J.; Adair, T.; Aggarwal, R.; Ahn, S.Y.; et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2095–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila-Cervantes, C.A. Cardiovascular disease in Mexico 1990–2017: Secondary data analysis from the global burden of disease study. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Naghavi, M.; Allen, C.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Casey, D.C.; Charlson, F.J.; Chen, A.Z.; Coates, M.M.; Coggeshall, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1459–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Upadhyay, R.K. Emerging Risk Biomarkers in Cardiovascular Diseases and Disorders. J. Lipids 2015, 2015, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreatsoulas, C.; Anand, S.S. The impact of social determinants on cardiovascular disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 2010, 26, 8C–13C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mannu, G.S.; Zaman, M.J.; Gupta, A.; Rehman, H.U.; Myint, P.K. Evidence of Lifestyle Modification in the Management of Hypercholesterolemia. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2013, 9, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rhodes, K.S.; Weintraub, M.; Marchlewicz, E.H.; Rubenfire, M.; Brook, R.D. Medical nutrition therapy is the essential cornerstone for effective treatment of “refractory” severe hypertriglyceridemia regardless of pharmaceutical treatment: Evidence from a Lipid Management Program. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2015, 9, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikand, G.; Cole, R.E.; Handu, D.; Dewaal, D.; Christaldi, J.; Johnson, E.Q.; Arpino, L.M.; Ekvall, S.M. Clinical and cost benefits of medical nutrition therapy by registered dietitian nutritionists for management of dyslipidemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2018, 12, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilat-Adar, S.; Sinai, T.; Yosefy, C.; Henkin, Y. Nutritional Recommendations for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3646–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- American Diabetes Association. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care 2020, 43 (Suppl. 1), S111–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jeong, S.J. Nutritional approach to failure to thrive. Korean J. Pediatr. 2011, 54, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evert, A.B.; Dennison, M.; Gardner, C.D.; Garvey, W.T.; Lau, K.H.K.; MacLeod, J.; Mitri, J.; Pereira, R.F.; Rawlings, K.; Robinson, S.; et al. Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 731–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Mestral, C.; Khalatbari-Soltani, S.; Stringhini, S.; Marques-Vidal, P. Fifteen-year trends in the prevalence of barriers to healthy eating in a high-income country. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Douglas, C.C.; Lawrence, J.C.; Bush, N.C.; Oster, R.A.; Gower, B.A.; Darnell, B.E. Ability of the Harris-Benedict formula to predict energy requirements differs with weight history and ethnicity. Nutr. Res. 2007, 27, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Subar, A.F.; Freedman, L.S.; A Tooze, J.; I Kirkpatrick, S.; Boushey, C.J.; Neuhouser, M.L.; E Thompson, F.; Potischman, N.; Guenther, P.M.; Tarasuk, V.; et al. Addressing Current Criticism Regarding the Value of Self-Report Dietary Data. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2639–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Mestral, C.; Khalatbari-Soltani, S.; Stringhini, S.; Marques-Vidal, P. Perceived barriers to healthy eating and adherence to dietary guidelines: Nationwide study. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2580–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landa-Anell, M.V.; Melgarejo-Hernández, M.A.; García-Ulloa, A.C.; Del Razo-Olvera, F.M.; Velázquez-Jurado, H.R.; Hernández-Jiménez, S. Barriers to adherence to a nutritional plan and strategies to overcome them in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus; results after two years of follow-up. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2020, 67, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leon, A.; Roemmich, J.N.; Casperson, S.L. Identification of Barriers to Adherence to a Weight Loss Diet in Women Using the Nominal Group Technique. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinsier, R.L.; Seeman, A.; Herrera, M.G.; Simmons, J.J.; Collins, M.E. Diet Therapy of Diabetes: Description of a Successful Methodologic Approach to Gaining Diet Adherence. Diabetes 1974, 23, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, D.K.; Mitchell, R.D.; Ambler, J.; Tattersall, R.B. Influence of imaginative teaching of diet on compliance and metabolic control in insulin dependent diabetes. BMJ 1983, 287, 1858–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Desroches, S.; Lapointe, A.; Ratté, S.; Gravel, K.; Légaré, F.; Turcotte, S. Interventions to enhance adherence to dietary advice for preventing and managing chronic diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 1–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- A Kendall, P.; Jansen, C.M.; Sjogren, D.D.; Jansen, G.R. A comparison of nutrient-based and exchange-group methods of diet instruction for patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1987, 45, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ross, R.; Neeland, I.J.; Yamashita, S.; Shai, I.; Seidell, J.; Magni, P.; Santos, R.D.; Arsenault, B.; Cuevas, A.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: A Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.J.; Barnes, K.A.; Ball, L.E.; Mitchell, L.J.; Sladdin, I.; Lee, P.; Williams, L.T. Effectiveness of dietetic consultation for lowering blood lipid levels in the management of cardiovascular disease risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 76, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, L.E.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.M.; Hill, M.N. Compliance with cardiovascular disease prevention strategies: A review of the research. Ann. Behav. Med. 1997, 19, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkin, Y.; Garber, D.W.; Osterlund, L.C.; Darnell, B.E. Saturated Fats, Cholesterol, and Dietary Compliance. Arch. Intern. Med. 1992, 152, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, A.M.; White, M.A.; Grilo, C.M.; Sinha, R. Examining the effects of cigarette smoking on food cravings and intake, depressive symptoms, and stress. Eat. Behav. 2017, 24, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diekman, C.; Malcolm, K. Consumer Perception and Insights on Fats and Fatty Acids: Knowledge on the Quality of Diet Fat. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 54, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glueck, C.; Gordon, D.; Nelson, J.; Davis, C.; Tyroler, H. Dietary and Other Correlates Of Changes In Total And Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol In Hypercholesterolemic Men: The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1986, 44, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Principal Objective | Material for Visit | |

|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Identifying foods that increase triglycerides and cholesterol. To provide a personalized plan based on each participant’s characteristics. To assess barriers to adherence to nutritional treatment. | Color information cards: “Foods that increase triglycerides and foods that increase cholesterol.” Simplified nutritional plan according to traffic light colors or a food exchange list. Color cards with different strategies were provided to solve each of the barriers, i.e., “What can I do if I eat outside my home?” or “How do you read food labels?” |

| Telephone visit | To assess adherence to diet by self-reports. To solve patient questions and concerns. | Telephone interview: To ask patients to rate adherence themselves on a scale of 0 to 100. Provide advice. |

| Visit 2 | Evaluation of adherence by a 3-day or 24-h food recall. We compared the quantity and quality of food against the recommended portions. Identification of barriers and solutions. Examples of breakfast, lunch, or dinners according to their nutritional plan. Healthy snacks. | A 3-day or 24-h food recall. Color cards with different strategies to solve each of the barriers. Written information. Color cards with different options. |

| Telephone visit | To assess diet adherence through a self-report. To solve patient questions and concerns. | Telephone interview: To ask patients to rate adherence themselves on a scale of 0 to 100. Provide advice. |

| Visit 3 | Evaluation of adherence by a 3-day or 24-h food recall. We compared the quantity and quality of food against the recommended portions. Identification of barriers and solutions. | A 3-day or 24-h food recall. Color cards with different strategies to solve each of the barriers. |

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex Female Male | 61 (57.5%) 45 (42.5%) |

| Age | 46.8 ± 12.5 |

| Years of study | 13.5 (9–19) |

| Current smoker Yes | 22 (20.7%) |

| Current alcohol consumption Yes | 41 (38.6%) |

| Type 2 diabetes Yes | 21 (19.8%) |

| Hypertension Yes | 27 (25.4%) |

| Family history of Dyslipidemia Yes | 64 (60.3%) |

| Type of Dyslipidemia Primary Secondary | 59 (55.7%) 47 (44.3%) |

| Dyslipidemia Treatment Statins Fibrates Ezetimibe Niacin Omega 3 Other No treatment | 95 (89.6%) 53 (50%) 11 (10.3%) 1 (0.9%) 11 (10.3%) 1 (0.9%) 11 (10.4%) |

| Barriers to Adhering to Nutritional Treatment | Visit 1 n (%) | Visit 2 n (%) | Visit 3 n (%) | p-Value § |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of information about a correct diet for dyslipidemias | 14 (13) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Economic situation (“Being on a diet is very expensive”) | 12 (11) | 7 (7) | 1 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Lack of time to prepare my meals | 24 (23) | 15 (14) | 4 (4) | <0.001 |

| I eat away from home most of the time | 20 (19) | 19 (18) | 2 (2) | <0.001 |

| I don’t need/want to make changes to my diet | 15 (14) | 14 (13) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| None | 21 (20) | 51 (48) | 98 (93) | <0.001 |

| V2 | V3 | p-Value of Differences between Visits p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy intake (kcal) Adherence (%) | 104.7 ± 26.2 | 95.4 ± 23.5 | 0.02 |

| Carbohydrate intake (grams) Adherence (%) | 126.8 ± 43.1 | 112.4 ± 35.5 | 0.08 |

| Protein intake (grams) Adherence (%) | 104.8 ± 30.3 | 96.6 ± 29.4 | 0.06 |

| Fat intake (grams) Adherence (%) | 100.3 ± 30.9 | 65.1 ± 19.6 | < 0.001 |

| General Adherence (%) per day | 108.6 ± 31.3 | 93.0 ± 22.1 | < 0.001 |

| Patient Adherence § Good 80–110% Bad <80% or >110% | 43 (40.5%) 63 (59.4%) | 57 (53.8%) 49 (46.2%) | 0.56 |

| Self-reported adherence (%) * Telephone visit 1 | 60 (40–80) | 70 (70–80) | < 0.001 |

| Factors | B Coefficient | S.E (Standard Error) | Wald | p-Value | Exp (B) | CI (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female Sex | 0.97 | 0.47 | 4.15 | 0.04 | 2.64 | 1.03–6.74 |

| Smoking | 1.11 | 0.53 | 4.46 | 0.03 | 3.06 | 0.11–0.92 |

| Prescribed >1500 kcal | 1.88 | 0.64 | 8.50 | 0.004 | 6.56 | 0.04–0.54 |

| No Barriers at V3 | −3.18 | 1.07 | 8.77 | 0.084 | 4.59 | 0.81–25.9 |

| Characteristic | Baseline | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Weight (kg) * § τ | 72.1 ± 15.4 | 71.1 ± 15.4 | 71.2 ± 15.4 | 0.005 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 27.1 ± 4.2 | 26.9 ± 4.6 | 26.9 ± 4.6 | 0.29 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) | 120 (110–130) | 120 (110–120) | 120 (110–132) | 0.24 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) | 80 (70–80) | 80 (78–80) | 78 (70–80) | 0.17 |

| Waist (cm) * § τ | 92.6 ± 12.6 | 91.5 ± 12.1 | 90.8 ± 11.9 | <0.001 |

| Energy intake (kcal) * § τ | 1912 ± 645.1 | 1722.2 ± 496.7 | 1547.6 ± 338.7 | <0.001 |

| Carbohydrate intake (grams) * § τ | 266.6 ± 113.7 | 228.3 ± 85.3 | 193.9 ± 53.5 | <0.001 |

| Protein intake (grams) * § τ | 88.9 ± 32.8 | 86.4 ± 27.8 | 80.6 ± 23.6 | <0.001 |

| Fat intake (grams) § | 63.8 ± 27.9 | 64.0 ± 20.6 | 41.3 ± 10.8 | <0.001 |

| Fiber (grams/day) * § | 29.1 ± 12.1 | 26.4 ± 7.9 | 23.4 ± 6.8 | <0.001 |

| Physical activity > 150 min/week YES/NO | 48 (45.2%) | 57 (53.3%) | 49 (46.2%) | 0.46 |

| Minutes/visit * § τ | 60 (50–60) | 35 (35–35) | 30 (30–30) | <0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 102.0 ± 23.9 | 108.3 ± 48.0 | 102.0 ± 28.6 | 0.51 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.85 ± 0.34 | 0.85 ± 0.37 | 0.88 ± 0.36 | 0.65 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) * § τ | 215.0 (125.7–293) | 179.5 (127.5–280) | 165.5 (113.5–235) | <0.001 |

| Goal Triglycerides (<150 mg/dL) * § τ | 34 (32.1%) | 40 (37.7%) | 44 (41.5%) | <0.001 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) * § τ | 215.2 ± 56.7 | 202.7 ± 56.7 | 198.4 ± 49.7 | <0.001 |

| Goal Total Cholesterol (<200 mg/dL) * § | 44 (41.5%) | 45 (42.4%) | 54 (51%) | <0.001 |

| HDL- Cholesterol (mg/dL) § τ | 43.6 ± 13.6 | 42.1 ± 13.6 | 44.4 ± 14.4 | 0.09 |

| Goal HDL-Cholesterol (>40 mg/dL) | (58.2%) | (55.2%) | (57.5%) | 0.008 |

| LDL-Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 135.5 ± 59.5 | 125.2 ± 46.9 | 124.7 ± 53.6 | 0.59 |

| Patients with diabetes (n = 21) HbA1c (%) | 7.1 ± 1.9 | 7.5 ± 2.1 | 7.5 ± 1.7 | 0.75 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Del Razo-Olvera, F.M.; Martin-Vences, A.J.; Brito-Córdova, G.X.; Elías-López, D.; Landa-Anell, M.V.; Melgarejo-Hernández, M.A.; Cruz-Bautista, I.; Manjarrez-Martínez, I.; Gómez-Velasco, D.V.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A. Primary Barriers of Adherence to a Structured Nutritional Intervention in Patients with Dyslipidemia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1744. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061744

Del Razo-Olvera FM, Martin-Vences AJ, Brito-Córdova GX, Elías-López D, Landa-Anell MV, Melgarejo-Hernández MA, Cruz-Bautista I, Manjarrez-Martínez I, Gómez-Velasco DV, Aguilar-Salinas CA. Primary Barriers of Adherence to a Structured Nutritional Intervention in Patients with Dyslipidemia. Nutrients. 2021; 13(6):1744. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061744

Chicago/Turabian StyleDel Razo-Olvera, Fabiola Mabel, Angélica J. Martin-Vences, Griselda X. Brito-Córdova, Daniel Elías-López, María Victoria Landa-Anell, Marco Antonio Melgarejo-Hernández, Ivette Cruz-Bautista, Iliana Manjarrez-Martínez, Donají Verónica Gómez-Velasco, and Carlos Alberto Aguilar-Salinas. 2021. "Primary Barriers of Adherence to a Structured Nutritional Intervention in Patients with Dyslipidemia" Nutrients 13, no. 6: 1744. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061744

APA StyleDel Razo-Olvera, F. M., Martin-Vences, A. J., Brito-Córdova, G. X., Elías-López, D., Landa-Anell, M. V., Melgarejo-Hernández, M. A., Cruz-Bautista, I., Manjarrez-Martínez, I., Gómez-Velasco, D. V., & Aguilar-Salinas, C. A. (2021). Primary Barriers of Adherence to a Structured Nutritional Intervention in Patients with Dyslipidemia. Nutrients, 13(6), 1744. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061744