“Food Is Our Love Language”: Using Talanoa to Conceptualize Food Security for the Māori and Pasifika Diaspora in South-East Queensland, Australia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Māori and Pasifika in Australia

1.2. Aims

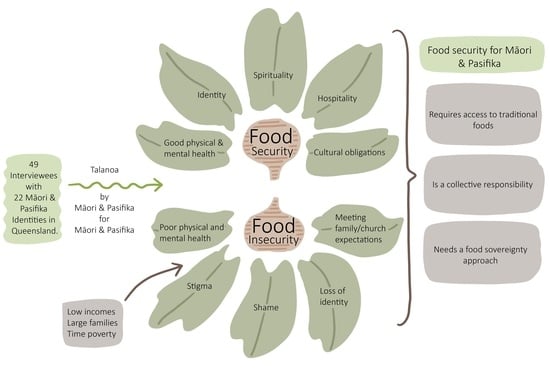

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Co-Analysis

Thematic Analysis

2.5. Reflexivity

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Identity—Food Is Central to Cultural Identity and Connects People, Families and Communities

In Chuukese there is a saying ‘food is bone’ which explains the centrality of food to life, to cultural, familial and communal shared experiences. In the way that bone provides the skeletal structure of the human body, so food is the framework to a holistic life and shared social and cultural experiences” (O_Federated States of Micronesia).

It’s sort of like a love language in ways… giving and receiving food. For example, when my father was in hospital and my mom was in town at the time, it was the fact that my friends showed up with food for us. That was a big deal for her (Y_Papua New Guinea).

Certain foods are shared in social occasions or functions and have higher value such as ufi (dalo) and so these are shared or gifted with families and members as a sign of respect… For instance, different parts of fish or meat are given to certain important members of the family (usually the head or the eldest (O_Fiji).

We had one (underground oven) at the premises and one again at campsite. We have a number of youths [who] turned up and you can tell they thoroughly enjoyed the experience. This is how we cook back at home, how our ancestors cooked. It wasn’t with an electric oven that we turn the thing on. It was with wood and rocks. (O_Niue).

3.2. Hospitality and Reciprocity

Hospitality is a big thing in our church, because it sort of creates that sense of connectedness again. So even at the moment through COVID, it’s been a little bit tough, because we haven’t been able to do like big connection groups like or big corporate gatherings. But when we do when we are able to have them, it’s always kind of centred around food when we have that time to connect off afterwards (Y_ Māori).

Hospitality, you know, people who would visit us, the first thing we would provide is a drink. And then after that, if they were staying longer then we would provide food and have a meal, for example. But food seems to be the thing that brings everyone together and then people share that hospitality, share that fellowship, [and] share the social side of things (O_ Rotuma).

Well, I think that, you know, what, some families, we’re that that are not so well off, I think that is excellent, as well. terms of, I suppose that they have to make sacrifices and struggle a bit in some areas, because, you know, their country, they have to contribute to the community. But it’s like a lot other Pacific Island communities here is very kind of communal type, you know, communal system, I suppose it’s kind of like a bit of, you know, reciprocal behaviour that goes on as well. Because if you have a function as well, you know, for example, that the people from your church will help you out too… (O_ Niue).

Inati basically means the sharing of food. It’s contributing to each family …When they call the Inati, it is always boys. It’s not voiced for the mothers or the fathers. It has always been said that, for us with the “moya tomaniti” (meaning our children), we say there is Inati happening at two o’clock this afternoon. Okay, so each family will go, one or two people will go to that Inati. ….So basically, what they do is they calculate how many people in that family and then they’ll share accordingly. A family of three cannot have the same amount as a family of 10. So, they actually distribute accordingly (O_ Tokelau).

So in my role, I’ve done home visits, things like that, if somebody offers me food I won’t turn it down. It’s rude. Where I’m from, it’s rude. And I’m also seeing people who don’t have lots of money who are in crisis. And if they’re offering me something, I’ll take it, because they’re offering. That offer in itself means a lot when they haven’t got enough (M_ Māori).

I don’t think it’s not as, I guess, taboo to not eat someone’s food that they’ve prepared for you. I guess if they prepared it specifically for you, then yes, you should have a plate or at least eat from the plate. There’s no real expectation for you to finish it. But there is an expectation for you to keep serving (Y_ Kiribati).

3.3. Spirituality

We are very connected to the process of food, the way we work and toil the land, and so we appreciate food, you know. It’s all connected and for us Pasifika you know food and the land, we [have to] thank God. It’s a spiritual connection that we have to the land and how it gives back to us (M_Tonga).

I’d say mainly because it’s one way that we show our appreciation or love. Because we don’t live on monetary things, especially in the Islands. And a lot of it is because you put a lot of time and effort into growing it and cultivating it, and then into harvesting it. You’ve put all this time and energy into this and you’re consuming it. So, you’re consuming that energy for your body (Y_Kiribati).

Not only the sacrament on Sunday, but the food that God provides for us every day is holy. And so therefore, we treat this as a provision that God has given to us to sustain our life, to develop us. Every holistic development of a human-being centres on this provision of God, and in your context this is food. So therefore, it is very important that food needs to be clean. Hygiene needs to come into all perspective of development, you know, gardening, growing, cooking, all those aspects; how to preserve them for the use of the family of the community, how to offer them in generosity to those who have come. And then they all are contained in God ‘Mana’.... that’s it (O_Rotuma).

3.4. Expectations and Obligations

I think there is definitely an expectation. I think there’s an expectation that if you want to be part of a community and being an active member, that everyone must contribute. So if everyone’s contributing food, then every member that turns up must contribute food. I think there’s that cultural expectation there. So I think for those who choose not to be involved, it could be a fact that they just financially aren’t able to contribute and then therefore cannot participate in those community events. And then that can kind of I guess impact our cultural identity, and not being able to be part of our cultural community can have such a massive impact (Y_Kiribati).

Mostly, because I give back. Yeah. So in my head, I’m like, it’s not something that I would expect. It’s something that I would do. More so out of obligation, rather than because I want to. Yeah. If that was the case, because it’s kind of that notion of you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours. Which to me is like, I don’t love it but, again because I think when I give or when I do it, there is the expectation and intention of not receiving. It’s purely for the intention of giving (Y_Māori).

I don’t feel like it should always be an expectation. I think if I knew that my brother or sister wasn’t working or were just making enough to provide for their own kids, that is expectation met. So it would be like if I’m hosting or having a big family dinner, the expectation is that they just turn up. I think it’s just about finding that balance, because I think some of the expectations are old school. Really, really old school. And for me, I guess, the way that I live now isn’t really applicable, or is not always applicable. So it’s hard to sort of follow them (Y_Māori).

But I think that it’s also dictated to by things such as changing priorities of young people, and the cost factor. For example, some young people, they just like a cup of tea, you know, some biscuits, sandwiches at their function… It is a lot easier to prepare. Usually when you’re providing a Pacific Island type meal, it takes a long time to prepare. It can be very costly as well. Some of the younger ones, you know, got mortgages, they’ve got kids or got sports fees, and so forth (O_Niue).

3.4.1. Expectations from Family

The view from the Islands with relatives is wealth but [they] do not realise that its more expensive to live here. I know there is an expectation for those of us overseas to contribute back home… One of the things that I’ve tried to do is explain to people back at home that some here and a significant number of Fijians and Pacific Islanders, they have to work two or three jobs to support their family. …. I know of people that are supporting their own families back home, they pay their electricity bill and everything else, including food.” (O_Fiji, Samoa, Cook Islands, Māori).

3.4.2. Expectations from Churches

I think the role of the churches in its pastoral care is important that we look at people who do not have and to send food or think how do we help them?… The money that God gives us as a gift can be channelled to other important things in the lives of the people because the church is a people. (O_Rotuma).

I found out why a lot of people weren’t coming [to church]. Because they didn’t have the koha (donation) (O_Niue).

It can become a burden to the people that they are helping or an expectation from them to contribute… It’s a sad thing to say, but I think it’s more than the forcefulness of it… It’s like I need you in the church to show that our church is growing, that’s why they do what they do… (O_Samoa).

Unfortunately, there’s also a lot of people that do not have that support. They don’t attend any churches, they pretty much like live on their own really and are not involved in any of their respective communities and cultural communities. So they’re the ones that will go without having family and social support around them (O_ Samoa).

3.5. Stigma and Shame

But I think in terms of anyone who shows up to an event where there’s no food, it will be looked down upon. And probably classified as rude. It could just be they just don’t have any money to be able to provide it and it’s kind of a no-win situation sometimes which I find it really harsh in our culture (M_Samoa).

It’s sad, I see this a lot. When families haven’t got anything to contribute, they stay home. Because sometimes it’s a shame to go to our traditional thing when we know everyone else will be putting in something, and I don’t have anything to put in. Because usually this time, they sometimes read out names. And if your name doesn’t get read out, it can be a very shameful experience. So the family doesn’t go. So what happens is more and more people don’t go because [of] their financial (issues) (O_Niue).

In my experience, the majority of the time this struggle was never expressed outside the family. So in the same way, as the individual might not talk about, might not bring their struggle to the community space… Maybe it’s viewed as weakness, maybe as soon as they don’t want to impose on the space, or the community (Y_Samoa).

I think there’s still a lot … to learn, you know, when you’re doing it tough to put your hand up. You know, again, it comes down to that sense of pride, where you don’t want people to know or anyone else to know what you’re going through. (O_Cook Islands).

Because I think it’s a hard thing to go and ask for free food. Yeah, it’s shame. Men are supposed to be supporting your family providing for your family and you and you can’t even provide the basic of food on the table. I think it really took a kick in the gut kind of thing for them (Y_Tonga).

Well, I can speak on behalf of men. And I know that for any normal man that can’t put food on the table, it would be quite devastating. He would feel inadequate, and as if he wasn’t doing his job properly. Especially if there’s kids in the family. …. Because in Nauru, you don’t really have a problem with providing food on the table, because you can just go and catch fish. And yeah, you can get everything you need off the land and off the sea (O_Nauru).

3.6. Physical and Mental Health

So let’s say you have two parents, and a large family. Between them working, then looking after the kids then coming home? The question is like, Where’s the time to produce a good meal? Like where is the energy if they’re running between looking after, maybe there’s, a five-year-old and a sixteen-year-old, between them playing sports or juggling a lot of things? (Y_Samoa).

There may be the lack of knowledge and understanding the lack of skills to be able to know what to do with some of the different variety of foods. So one of the problems we have is too many portions, now we have too easy access. It’s not really appreciated, we just buy a whole bunch, and we’re eating copious amounts in every meal, because we went for the money and we’re just trading with money. And so because of that disconnect of that cycle of development, growth, distribution, evening out that cycle in the Islands is almost a little bit different now (M_Tonga).

4. Discussion

4.1. Cultural Food Security

4.2. Food Insecurity as a Collective Responsibility

4.3. Moving to a Food Sovereingty Approach

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- HLPE. Food Security and Nutrition: Building a Global Narrative Towards 2030. In A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Coming to Terms with Terminology: Food Security, Nutrition Security, Food Security and Nutrition, Food and Nutrition Security; Committee on World Food Security: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, C.M.; Booth, S. Food insecurity and hunger in rich countries—It is time for action against inequality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alonso, B.E.; Cockx, L.; Swinnen, J. Culture and food security. Glob. Food Sec. 2018, 17, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramsey, R.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G.; Gallegos, D. Food insecurity among Australian children: Potential determinants, health and developmental consequences. J. Child Health Care 2011, 15, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.M.C.; Miller, D.P.; Morrissey, T.W. Food insecurity and child health. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20190397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramsey, R.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G.; Gallegos, D. Food insecurity among adults residing in disadvantaged urban areas: Potential health and dietary consequences. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dean, E.B.; French, M.T.; Mortensen, K. Food insecurity, health care utilization, and health care expenditures. Health Serv. Res. 2020, 55 (Suppl. S2), 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Radak, T.; Khubchandani, J.; Dunn, P. Food insecurity and mortality in American adults: Results from the NHANES-linked mortality study. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 22, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundersen, C.; Tarasuk, V.; Cheng, J.; De Oliveira, C.; Kurdyak, P. Food insecurity status and mortality among adults in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J.B.; Bernard, D.; Liang, L. The prevalence of food insecurity is highest among Americans for whom diet is most critical to health. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, e131–e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.J.; Garacci, E.; Ozieh, M.; Egede, L.E. Food insecurity and glycemic control in individuals with diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes in the United States. Prim. Care Diabetes 2021, 15, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.D. Food insecurity and mental health status: A global analysis of 149 countries. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elgar, F.J.; Pickett, W.; Pförtner, T.-K.; Gariépy, G.; Gordon, D.; Georgiades, K.; Davison, C.; Hammami, N.; MacNeil, A.H.; Azevedo Da Silva, M.; et al. Relative food insecurity, mental health and wellbeing in 160 countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 268, 113556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiee, M.; Vatanparast, H.; Janzen, B.; Serahati, S.; Keshavarz, P.; Jandaghi, P.; Pahwa, P. Household food insecurity is associated with depressive symptoms in the Canadian adult population. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Men, F.; Elgar, F.J.; Tarasuk, V. Food insecurity is associated with mental health problems among Canadian youth. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallegos, D.; Eivers, A.; Sondergeld, P.; Pattinson, C. Food insecurity and child development: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M.; Rikard-Bell, G.; Mohsin, M.; Williams, M. Food insecurity in three socially disadvantaged localities in Sydney, Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2006, 17, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seivwright, A.N.; Callis, Z.; Flatau, P. Food insecurity and socioeconomic disadvantage in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerz, A.; Bell, K.; White, M.; Thompson, A.; Suter, M.; McKechnie, R.; Gallegos, D. Development and preliminary validation of a brief household food insecurity screening tool for paediatric health services in Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 1538–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, L.M.; O’Sullivan, T.A.; Ryan, M.M.; Lo, J.; Devine, A. Utilising a multi-item questionnaire to assess household food security in Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2019, 30, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, R.; John, J.R.; Liamputtong, P.; Arora, A. Prevalence and risk factors of food insecurity among Libyan migrant families in Australia. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, H.J.; McKay, F.H. Food as a discretionary item: The impact of welfare payment changes on low-income single mother’s food choices and strategies. J. Poverty Soc. Justice 2017, 25, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.B.; Booth, S.; Pollard, C.M. Social assistance payments and food insecurity in Australia: Evidence from the Household Expenditure Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, M.D.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Who are the world’s food insecure? New evidence from the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale. World Dev. 2017, 93, 402–412. [Google Scholar]

- Chilton, M.; Knowles, M.; Bloom, S.L. The intergenerational circumstances of household food insecurity and adversity. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2017, 12, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chilton, M.; Knowles, M.; Rabinowich, J.; Arnold, K.T. The relationship between childhood adversity and food insecurity: ‘It’s like a bird nesting in your head’. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2643–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Odoms-Young, A.; Bruce, M.A. Examining the impact of structural racism on food insecurity: Implications for addressing racial/ethnic disparities. Fam. Community Health 2018, 41 (Suppl. S2), S3–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phojanakong, P.; Brown Weida, E.; Grimaldi, G.; Lê-Scherban, F.; Chilton, M. Experiences of racial and ethnic discrimination are associated with food insecurity and poor health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conroy, A.A.; Cohen, M.H.; Frongillo, E.A.; Tsai, A.C.; Wilson, T.E.; Wentz, E.L.; Adimora, A.A.; Merenstein, D.; Ofotokun, I.; Metsch, L. Food insecurity and violence in a prospective cohort of women at risk for or living with HIV in the US. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batley, J. What Does the 2016 Census Reveal about Pacific Islands Communities in Australia? Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McGavin, K.J.T.C.P. Being “nesian”: Pacific Islander identity in Australia. Contemp. Pac. 2014, 26, 126–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durham, J.; Fa’avale, N.; Fa’avale, A.; Ziesman, C.; Malama, E.; Tafa, S.; Taito, T.; Etuale, J.; Yaranamua, M.; Utai, U.; et al. The impact and importance of place on health for young people of Pasifika descent in Queensland, Australia: A qualitative study towards developing meaningful health equity indicators. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enari, D.; Faleolo, R. Pasifika collective well-being during the COVID-19 crisis: Samoans and Tongans in Brisbane. J. Indig. Soc. Dev. 2020, 9, 110–126. [Google Scholar]

- Faleolo, R. Pasifika diaspora connectivity and continuity with Pacific homelands: Material culture and spatial behaviour in Brisbane. Aust. J. Anthropol. 2020, 31, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, S.M.; Ilalio, T. Maori and Pacific Islander overrepresentation in the Australian criminal justice system—What are the determinants? J. Offender Rehabil. 2016, 55, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L. The subjective experience of Polynesians in the Australian health system. Health Soc. Rev. 2013, 22, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.; George, J.R.; McDonald, B. An inconvenient truth: Why evidence-based policies on obesity are failing Māori, Pasifika and the Anglo working class. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2017, 12, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, K.; Ward, P.; Grace, B.S.; Gleadle, J. Social disparities in the prevalence of diabetes in Australia and in the development of end stage renal disease due to diabetes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia and Maori and Pacific Islanders in New Zealand. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Queensland Government; Department of Health. Queensland Health’s Response to Pacific Islander and Māori Health Needs Assessment; Divison of the Chief Health Officer, Queensland Health: Brisbane, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, K.C.; Ware, R.; Felise Tautalasoo, L.; Stanley, R.; Scanlan-Savelio, L.; Schubert, L. Dietary habits of Samoan adults in an urban Australian setting: A cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallegos, D.; Do, H.; Gia To, Q.; Vo, B.; Goris, J.; Alraman, H. Eating and physical activity behaviours among ethnic groups in Queensland, Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1991–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Power, E.M. Conceptualizing food security for Aboriginal people in Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2008, 99, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, P. “Unsophisticated and unsuited”: Australian barriers to Pacific Islander immigration from New Zealand. Political Sci. 2014, 66, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. The fiscal impact of the trans-Tasman travel arrangement: Have the costs become too high? Aust. Tax Forum 2018, 33, 249–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, J.; Campbell, J. Climate change and migration: The case of the Pacific Islands and Australia. J. Pac. Stud. 2016, 36, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chilton, M.; Rose, D. A rights-based approach to food insecurity in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaioleti, T.M. Talanoa research methodology: A developing position on Pacific research. Waikato J. Educ. 2006, 12, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, M. Concept mapping, mind mapping and argument mapping: What are the differences and do they matter? Higher Educ. 2011, 62, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindrola-Padros, C.; Johnson, G.A. Rapid techniques in qualitative research: A critical review of the literature. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, D.; Chilton, M.M. Re-evaluating expertise: Principles for food and nutrition security research, advocacy and solutions in high-income countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKerchar, C.; Bowers, S.; Heta, C.; Signal, L.; Matoe, L. Enhancing Māori food security using traditional kai. Global Health Promot. 2015, 22, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeke-Pickering, T.; Heitia, M.; Heitia, S.; Karapu, R.; Cote-Meek, S. Understanding Maori food security and food sovereignty issues in Whakatane. Mai J. 2015, 4, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, R.; McIlvaine-Newsad, H. Gardening in green space for environmental justice: Food security, leisure and social capital. Leisure/Loisir 2013, 37, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecerof, S.S.; Stafström, M.; Westerling, R.; Östergren, P.-O. Does social capital protect mental health among migrants in Sweden? Health Promot. Int. 2015, 31, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Du Plooy, D.R.; Lyons, A.; Kashima, E.S. Social capital and the well-being of migrants to Australia: Exploring the role of generalised trust and social network resources. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 79, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M.; Annas, J. Feeling good and functioning well: Distinctive concepts in ancient philosophy and contemporary science. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Well-being, agency and freedom: The Dewey lectures 1984. J. Philos. 1985, 82, 169–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.G.; Grinter, R.E. Collectivistic health promotion tools: Accounting for the relationship between culture, food and nutrition. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2014, 72, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanham, A.; Lubari, E.; Gallegos, D.; Radcliffe, B. Health promotion in emerging collectivist communities: A study of dietary acculturation in the South Sudanese community in Logan City, Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2022, 33, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations; McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Renzaho, A.M.N.; Mellor, D. Food security measurement in cultural pluralism: Missing the point or conceptual misunderstanding? Nutrition 2010, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, N.; Marzban, M.; Sebar, B.; Harris, N. Religious identity and psychological well-being among middle-eastern migrants in Australia: The mediating role of perceived social support, social connectedness, and perceived discrimination. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2020, 12, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, S.; Begley, A.; Mackintosh, B.; Kerr, D.A.; Jancey, J.; Caraher, M.; Whelan, J.; Pollard, C.M. Gratitude, resignation and the desire for dignity: Lived experience of food charity recipients and their recommendations for improvement, Perth, Western Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 2831–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osei-Kwasi, H.A.; Nicolaou, M.; Powell, K.; Holdsworth, M. “I cannot sit here and eat alone when I know a fellow Ghanaian is suffering”: Perceptions of food insecurity among Ghanaian migrants. Appetite 2019, 140, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryland, R.; Carroll, J.-A.; Gallegos, D. Moving beyond Coping to Resilient Pragmatism in Food Insecure Households. J. Poverty 2021, 25, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Voices of the Hungry: The Food Insecurity Experience Scale. Available online: https://www.fao.org/in-action/voices-of-the-hungry/fies/en/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- FAO; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. In Transforming Food Systems for Food Security, Improved Nutrition and Affordable Healthy Diets for All; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, A.; Bambrick, H.; Gallegos, D. Climate extremes constrain agency and long-term health: A qualitative case study in a Pacific Small Island Developing State. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2021, 31, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.K.; Robin, T. Healthy on our own terms. Crit. Diet. 2020, 5, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, C.; Kerr, R.B.; Neufeld, H.; Steckley, M.; Wilson, K.; Dokis, B. Supporting food security for Indigenous families through the restoration of Indigenous foodways. Can. Geogr. 2021, 65, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Secure Canada. What is Food Sovereignty? Available online: https://foodsecurecanada.org/who-we-are/what-food-sovereignty (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Jarosz, L. Comparing food security and food sovereignty discourses. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2014, 4, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, A.M.; Hergesheimer, C.; Brisbois, B.; Wittman, H.; Yassi, A.; Spiegel, J.M. Food sovereignty, food security and health equity: A meta-narrative mapping exercise. Health Policy Plan. 2014, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shattuck, A.; Schiavoni, C.M.; VanGelder, Z. Translating the politics of food sovereignty: Digging into contradictions, uncovering new dimensions. Globalizations 2015, 12, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Ray, L.; Burnett, K.; Cameron, A.; Joseph, S.; LeBlanc, J.; Parker, B.; Recollet, A.; Sergerie, C. Examining Indigenous food sovereignty as a conceptual framework for health in two urban communities in Northern Ontario, Canada. Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26 (Suppl. S3), 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durham, J.; Tafa, S.; Etuale, J.; Nosa, V.; Fa’avale, A.; Malama, E.; Yaranamua, M.; Taito, T.; Ziesman, C.; Fa’avale, N. Belonging in multiple places: Pasifika young peoples’ experiences of living in Logan. J. Youth Stud. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultural Identity | Participants |

|---|---|

| Cook Islands | 1 |

| Federated States of Micronesia | 1 |

| Fiji | 5 |

| Kiribati | 1 |

| Kiribati/Australia | 1 |

| Māori/Pakeha | 2 |

| Māori | 5 |

| Māori/Cook Islands | 1 |

| Nauru/Australia | 1 |

| Niue | 3 |

| Papua New Guinea | 4 |

| Rotuma | 1 |

| Samoa | 7 |

| Samoa/Fiji | 1 |

| Samoa/Māori/Irish | 1 |

| Solomon Islands | 2 |

| Tokelau/Māori/Tuvalu/Cook Islander | 2 |

| Tokelau | 2 |

| Tonga | 4 |

| Tonga/Australia | 2 |

| Tuvalu | 1 |

| French Polynesian-Tahiti/Māori | 1 |

| Total | 49 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akbar, H.; Radclyffe, C.J.T.; Santos, D.; Mopio-Jane, M.; Gallegos, D. “Food Is Our Love Language”: Using Talanoa to Conceptualize Food Security for the Māori and Pasifika Diaspora in South-East Queensland, Australia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102020

Akbar H, Radclyffe CJT, Santos D, Mopio-Jane M, Gallegos D. “Food Is Our Love Language”: Using Talanoa to Conceptualize Food Security for the Māori and Pasifika Diaspora in South-East Queensland, Australia. Nutrients. 2022; 14(10):2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102020

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkbar, Heena, Charles J. T. Radclyffe, Daphne Santos, Maureen Mopio-Jane, and Danielle Gallegos. 2022. "“Food Is Our Love Language”: Using Talanoa to Conceptualize Food Security for the Māori and Pasifika Diaspora in South-East Queensland, Australia" Nutrients 14, no. 10: 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102020

APA StyleAkbar, H., Radclyffe, C. J. T., Santos, D., Mopio-Jane, M., & Gallegos, D. (2022). “Food Is Our Love Language”: Using Talanoa to Conceptualize Food Security for the Māori and Pasifika Diaspora in South-East Queensland, Australia. Nutrients, 14(10), 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102020