Qualitative Studies of Infant and Young Child Feeding in Lower-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Dietary Patterns

Abstract

:1. Introduction

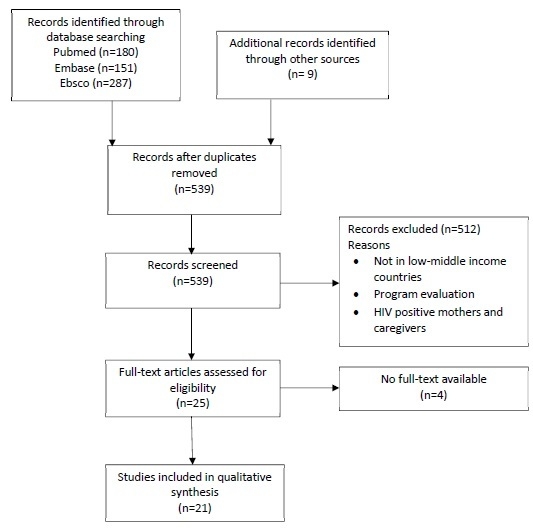

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Appraisal

- Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

- Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

- Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

- Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

- Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

- Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

- Have critical issues been taken into consideration?

- Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

- Is there a clear statement of findings?

- How valuable is the research?

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Date of Search | Search Terms | Total Articles Returned |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pubmed | 9 July 2016 | “infant nutritional physiological phenomena” (MeSH Terms) AND “qualitative research” (MeSH Terms) AND (“13 July 2006” (PDat): “9 July 2016” (PDat) AND “humans” (MeSH Terms) AND English (lang)) | 180 articles |

| Ebsco | 9 July 2016 | ((MH “Infant Nutritional Physiology+”) OR (MH “Infant Feeding+”)) AND Qualitative studies Limiters-Published Date: 1 January 2006–31 December 2016; English Language; Abstract Available; Human; Language: English Search modes-Find all my search terms | 287 articles |

| Embase | 9 July 2016 | ‘infant feeding’/exp OR ‘infant feeding’ OR ‘complementary feeding’/exp OR ‘complementary feeding’ AND (‘qualitative research’/exp OR ‘qualitative research’) AND (embase)/lim AND (2006–2016)/py AND (humans)/lim | 151 articles |

Appendix B

| Study No. | Author and Title | Participant Characteristics | Key Outcomes Reported | Emergent Findings (Finding Numbers from Table 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies Identified from Search Databases | ||||

| 1 | Lynn M. Babington Understanding Beliefs, Knowledge, and Practices of Mothers in the Dominican Republic Related to Feeding Infants and Young Children | Mothers’ ages ranged from 16 to 45 (mean age = 25), “The highest educational level attained was as follows: one had attended university (did not graduate), two had graduated from secondary school, one had completed eighth grade, three had completed sixth grade, two had completed fourth grade, and one had never attended school. When asked how well they spoke and/or understood English, two said “a little,” and the other eight answered “not at all.” The estimated yearly income for the entire family was reported by all 10 participants as less than 28,500 pesos ($868 U.S. dollars).” | From abstract: “The women who participated in the focus group all breast fed their babies with the belief that breast milk is better for infants than formula. Cereal, fruits, and vegetables are the main diet for children under 3 years old. Typically, “fast foods” and snack foods are not readily available and therefore they are rarely consumed. Obesity was viewed as a health risk for children. These mothers were practicing many healthy feeding behaviors, such as breastfeeding and limiting fats and sweets for young children, and they recognized their importance in promoting the health of children.” Additional notes: Participants universally practiced breastfeeding in part because formula is expensive and not readily available. They recognized the association between breastfeeding and the health of their babies. They all learned to breastfeed from their mothers/grandmother/sisters and said that everyone in the DR learns this way. Older mothers mentioned that breastfeeding has a negative effect on the physical appearance of their breasts but that this did not impact their decision to breastfeed because formula is not affordable. Mothers said they avoid giving fast foods and snack foods (which are not readily available), greasy/fatty foods, and sweats to young children. Since they do not give greasy/fatty foods to young children, they do not give much meat until around 3 years because it is greasy. Participants said that 3 years is the age when children eat what everyone else in the house eats in the DR. | (1) (59) (65) (68) |

| 2 | Amal Omer-Salim, Lars-Ake Persson, PiaOlsson Whom can I rely on? Mothers’ approaches to support for feeding: An interview study in suburban Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | Mothers were aged 16–30 years. Four women had no formal education, two had completed primary education and two had completed secondary education. Five of the women were homemakers and three were either formally employed or self-employed | From abstract: “The study revealed four categories of mothers’ perceptions of baby feeding: (1) baby feeding, housework and paid work have to adjust to each other; (2) breast feeding has many benefits; (3) water or breast milk can be given to quench baby’s thirst; and (4) crying provides guidance for baby feeding. Four different themes describing approaches to support emerged from the data: (1) adhering to diverse sources; (2) relying wholeheartedly on a mother figure; (3) working as a parental team; and (4) making arrangements for absence from the child.” Additional notes: Mothers believed breastfeeding makes babies healthy and prevents diseases. Also, breastfeeding was viewed as a cheap and hygienic option. Some believe colostrum is good for the baby and so initiated breastfeeding soon after birth, but some women did not believe this and discard it. Good nutrition for the mother thought to improve breastmilk output. Some women practice exclusive breastfeeding believing that breastmilk is all a baby needs, but some think the baby also needs water (but they know that the water must be clean to give to baby). It is a traditional practice to give boiled water shortly after birth. Some believe that giving water relieves baby from constipation. Initial crying was recognized as a prompt for breastfeeding, but too much crying led mother to give water or porridge and was seen as a sign of hunger (traditional beliefs say porridge will solve this and baby will stop crying). Advice from HWs was sometimes inadequate (too general, or infeasible for mother). Advice from mother/mother-in-law/senior mother figure sometimes refutes the advice given by HWs. Support and agreement from the husband encourages breastfeeding. Praise from partner or HW encouraged mother to continue to exclusively breastfeed. Work interrupted optimal baby feeding for many mothers, but some mothers reported expressing breastmilk into a clean cup while working to continue to breastfeed the baby. | (11) (18) (24) (35) (59) (63) (64) (65) (66) (68) (69) |

| 3 | C Tawiah-Agyemang, BR Kirkwood, K Edmond, A Bazzano and Z Hill Early initiation of breast-feeding in Ghana: barriers and facilitators | Of the 52 recently delivered mothers: age ranged from under 20 to 45. The majority of them lived in rural areas (n = 43, 83%). Nearly half the mothers did not complete any education (n = 24, 46%); 10 attained primary school; and 18 had attained education beyond primary school. | From abstract: “The major reasons for delaying initiation of breast-feeding were the perception of a lack of breast milk, performing postbirth activities such as bathing, perception that the mother and the baby need rest after birth and the baby not crying for milk. Facilitating factors for early initiation included delivery in a health facility, where the staff encouraged early breastfeeding, and the belief in some ethnic groups that putting the baby to the breast encourages the milk.” Additional notes: Barriers for delayed initiation: The perception of a lack of breastmilk: including physical signs that milk is absent/insufficient, beliefs about colostrum, and traditional beliefs of when the milk comes in (believed to be on the third day for some cultural groups in the study). Some believed colostrum was not good for the baby and so discarded it or delayed initiation until white milk came in. Delayed initiation of breastfeeding beyond 12 h often led to prelacteal feeding. Facilitators: Delivery at a health facility facilitated early initiation of breastfeeding due to advice of HWs. | (7) (10) (13) (23) (25) (32) (38) (62) (63) (65) (67) |

| 4 | Gloria E. Otoo, Anna A. Lartey, Rafael Pérez-Escamilla Perceived Incentives and Barriers to Exclusive Breastfeeding Among Peri-urban Ghanaian Women | The ages of the 35 participants ranged from 19 to 49 (mean age was 27.5). They had 7.2 ± 3.6 years of formal education. All but 3 of the women were employed, with about half (n = 17) being traders. | From abstract: “Almost all of the participants believed that exclusive breastfeeding is the superior infant feeding method and should be practiced for the first 6 months postpartum. However, there was widespread belief that infants can be given water if it is clean. Mothers reported that exclusive breastfeeding was easier when breast milk began to flow soon after delivery. The main obstacles to exclusive breastfeeding identified were maternal employment, breast and nipple problems, perceived milk insufficiency, and pressure from family.” Additional notes: Mothers obtained advice on exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) at the antenatal care clinic, during hospital stay, or at the postnatal care clinics. (Nurses advised them of the recommended practices, even if the reasons they gave were inaccurate). Knowledge that “breastmilk is best” was a motivation for women to practice EBF. Facilitators to EBF: Observation that EBF resulted in less frequent and shorter duration of illness in infants was a motivator for EBF. Mothers felt that EBF makes babies grow strong, intelligent, and healthy. Young babies stomachs are not mature enough for anything other than breastmilk (this finding lacks some coherence as some women believed breastmilk alone was not sufficient–e.g., when a baby still cries or remains restless even after breastfeeding it is a sign they need other foods). Mothers believed that her nutrition influences breastmilk production and quality; cultural beliefs influenced what foods they should eat for improved breastmilk production. Mothers’ knowledge that poor water and sanitation could cause a child to get diarrhea if child had other water or foods was a motivator for EBF. Some believed water should not be given to babies because of (runoff) from the fertilizers and chemicals used in the agricultural industry contaminating their water supply. Barriers to EBF: Swollen breasts, abscesses, and sore nipples are barriers to breastfeeding. Work interferes with breastfeeding (short maternity leave, followed by inability to find a place to breastfeed when they return to work). Maternal sickness and death prevents breastfeeding (though only two participants said women with HIV cannot breastfeed). Infant sickness impairs breastfeeding (child may lose interest or not latch on), along with weak jaws which impact sucking ability of infant, prompting mother to give other food so baby does not lose weight. Some mothers believe breastfeeding makes their breasts sag and so refuse to breastfeed. Women are hesitant to breastfeed in public, even in their cars because they do not want people to see their breasts. Pressure from mothers/grandmothers to adopt the mixed feeding methods their generation had used impacts EBF (especially if grandmother is around when infant is crying, they assume breastmilk is not enough), then women resort to adding water or not practicing EBF. Lack of support from the baby’s father could also hinder breastfeeding. | (1) (6) (10) (21) (22) (31) (36) (37) (59) (60) (63) (65) |

| 5 | Luzmil A Hernandez, Marth A Lucia Vasqu Practices and beliefs about exclusive breastfeeding by women living in Commune 5 in Cali, Colombia | The women participating ranged from 20 to 33 years of age. Regarding the level of education, one of the women had done university studies, four had completed high school, 5 had not finished high school, and the remaining participants had been in grammar School. | From abstract: “Findings are presented in two parts: practices and beliefs in favor of exclusive breastfeeding and practices and beliefs that do not support exclusive breastfeeding. The prominent practices and beliefs in favor of exclusive breastfeeding are related to the mother´s bond with the child, preparation for breastfeeding during pregnancy, and family support. Among the practices and beliefs not supporting maternal breastfeeding, we must highlight the mother’s lack of confidence in her breast milk production.” Additional notes: Breastfeeding was associated with providing love to their child and strengthening their bond. Women were convinced that breastfed children will be healthier and smarter in the future. But, exclusive breastfeeding for six months was considered difficult, and required preparation. They want their milk to be of adequate quality and quantity for their child. Some grandmothers or other elders had ideas of ways mothers could improves these milk traits (e.g., consuming fennel water). Mothers, mothers-in-law and grandmothers helped prepare mothers to breastfeed through their own experiences. Some still felt that breastmilk alone would not be enough for their child. Especially if the child continued crying. Pain in the breast was another reason for not exclusively breastfeeding. Some mothers who exclusively breastfed reported their child had become dependent on the breast and it was then difficult to wean. Along this line, mothers believed that weaning would be easier if the child had already had milk from other sources. There is a belief that children are born with weak stomachs and something must be done to strengthen it and protect them from disease. Home preparations are often given tot eh child within days after birth for this purpose; these included bean tincture, bacon, or a liquid to purge the stomach. | (8) (10) (15) (36) (61) (65) |

| 6 | Sabrina Rasheed, Rukhsana Haider, Nazmul Hassan, Helena Pachon, Sanjeeda Islam, Chowdhury S.B. Jalal, Tina G. Sanghvi Why does nutrition deteriorate rapidly among children under 2 years of age? Using qualitative methods to understand community perspectives on complementary feeding practices in Bangladesh | Not stated | From abstract: “Lay perceptions about complementary feeding differ substantially from international complementary feeding recommendations. A large proportion of children do not consume sufficient amounts of complementary foods to meet their energy and micronutrient needs. There was a gap in knowledge about appropriate complementary foods in terms of quality and quantity and strategies to convert family foods to make them suitable for children. Complementary feeding advice from family members, peers, and health workers, the importance given to feeding young children, and time spent by caregivers in feeding influenced the timing, frequency, types of food given, and ways in which complementary feeding occurred.” Additional notes: Children were fed complementary foods prior to 6 months of age primarily due to the perception that breastmilk alone was inadequate as the child got older. Liquids were given to young babies, including formula, which was considered good to maintain the health of the baby. | (8) (10) (22) (46) (47) (48) (49) (51) (71) |

| 7 | Pranee C. Lundberg, Trieu Thi Ngoc Thu Breast-feeding attitudes and practices among Vietnamese mothers in Ho Chi Minh City | Age range: 25 to 40 years Range of education levels: primary school to bachelors degree Majority lived in extended families and they had one to three children. | From abstract: “Five categories of breastfeeding attitudes and practices were identified: breast-feeding best but not exclusive, cultural and traditional beliefs, infant feeding as a learning process, factors influencing decision to breastfeed, and intention to feed the child.” Additional notes: Mothers recognized that breastmilk is best, but none were exclusively breastfeeding. Many gave water because they think the baby gets thirsty and that water will prevent tongue disease. Most discarded colostrum thinking it is harmful for baby, but a few knew that it was beneficial to baby’s health. Some were afraid breastmilk alone is not enough for baby so they also gave formula. Mothers believed that breastmilk quality was linked to health of mother (an ill mother would produce inferior milk), and her ability to consume the traditional postnatal diet. Mothers followed traditional beliefs (e.g., what to eat and not eat; messaging) to improve breastmilk production. Mothers, mothers-in-law, and grandmothers encouraged breastfeeding, told them how to breastfeed and helped with housework to allow mother to rest (after childbirth) and care for infant. The process of learning about breastfeeding from various sources gave them increased knowledge, which lead to improved self-confidence. Husband support gave confidence in breastfeeding. Returning to work shortly after birth (mostly before 6 months) made breastfeeding difficult. Media influenced mother’s opinions of formula and baby foods and made them think they are good for baby. Lactation problems (sore and cracked nipples, engorgement, inadequate lactation) interrupted breastfeeding with formula as a replacement. Size of baby influenced breastfeeding: mothers said they would feed baby more if he/she was small. Some mothers fed baby when he/she cried. After 4 months, mothers believed breastmilk alone was not enough so would add formula and/or complementary foods. | (7) (10) (11) (18) (22) (26) (27) (32) (36) (59) (65) (66) (68) |

| 8 | Yati Afiyanti, Dyah Juliastuti Exclusive breastfeeding practice in Indonesia | Mothers were aged 19 to 36 years | The initial breastfeeding practice immediately after delivery impeded the mothers’ decisions to exclusively breastfeed. For example, some women believed their baby had been given formula by the health provided after birth, so they hesitated to breastfeed exclusively. The belief of insufficient production of breast milk lead mothers to wean their babies early. After weaning their babies, the mothers still had a desire to breastfeed. Mothers kept trying to breastfeed even though they had weaned their baby and reported breastmilk production had decline. Early weaning caused several consequences (e.g., decline in breastmilk, increase in spending, health problems for the baby), which continued to affect the mother’s and baby’s lives. Some women though their babies grew faster after weaning and they enjoyed the extra time they had to spend on their daily activities. Media promotion of formula, suggestions from peers and family, and the mothers need to work were reported as external factors which impeded exclusive breastfeeding. Internal factors which did this included lack of knowledge about exclusive breastfeeding, techniques to ensure effective breastfeeding (e.g., ensuring baby was satiated), not recognizing baby feeding cues and behaviors, and believing formula can make babies healthier. | (5) (8) (9) (10) (22) (26) (28) (32) (33) (34) |

| 9 | Hope Mei Hong Lee, Jo Durham, Jenny Booth, Vanphanom Sychareun A qualitative study on the breastfeeding experiences of first-time mothers in Vientiane, Lao PDR | Mothers’ ages ranged from 19 to 39. Three had attained primary education; 5 had completed lower secondary education; 5 had attained; and 3 had finished tertiary education. The majority of them were unemployed and/or housewife (n = 9). Six were employed. | From abstract: “Participants demonstrated positive attitudes towards breastfeeding and recognized its importance. Despite this, breastfeeding practices were suboptimal. Few exclusively breastfed for the first six months of the baby’s life and most of the first-time mothers included in the sample had stopped or planned to stop breastfeeding by the time the infant was 18 months of age. Work was named as one of the main reasons for less than ideal breastfeeding practices. Traditional beliefs and advice from health staff and the first-time mothers’ own mothers, were important influences on breastfeeding practices. First-time mothers also cited experiencing tension when there were differences in advice they received from different people.” Additional notes: Health staff assisted women to introduce breastmilk early, and many reported the importance of the child receiving the colostrum. Breastfeeding was also reported to strengthen the bond between mother and newborn. Breastfeeding was thought to save money, giving it an advantage. Family elders have important role in decisions related to child feeding and one elder thought it was important to include them to avoid conflicts in advice given by health staff. Some women reported inconsistent advice from these two groups. Some women had trouble managing exclusive breastfeeding and work, with many citing it as the main reason for stopping exclusive breastfeeding early. Support from family and support in the workplace were also cited as reasons for success in exclusive breastfeeding. Insufficient milk supply, compressed (inverted) nipple and the baby just stopping sucking were all reported reasons for ending exclusive breastfeeding early. Fear of breast deformation and embarrassment of breastfeeding at social functions were also cited as reasons for stopping breastfeeding. Elders in the family often advocated for early introduction of complementary foods despite this being contradictory to the advice of health personnel. | (8) (10) (11) (22) (24) (25) (28) (29) (33) (36) (37) (59) (61) (63) (65) (68) |

| 10 | Christy Bomer-Norton Timing of breastfeeding initiation in rural Haiti: A focused ethnography | The range of mothers’ ages was between 19 years and 43 years. Years of education attainment ranged from 0 to 13 years. | From abstract: “Mothers described baby care by birth attendants as well as actual and perceived health issues of the mother and child as some of the factors influencing timing of breastfeeding initiation.” Additional notes: All 25 mothers believed that breastfeeding, colostrum and mature milk, was good for baby’s health and they value providing these health benefits to their baby; baby’s health was a priority for mothers. Mothers exhibited comfort with breastfeeding (comfortable feeding in front of others) and had the feeling that breastfeeding was the normal way of infant feeding. | (7) (25) (30) (31) (33) (38) (62) (64) (65) |

| 11 | Anne Laterra, Mohamed A. Ayoya, Jean-Max Beauliere, M’mbakwa Bienfait, Helena Pachon Infant and young child feeding in four departments in Haiti; mixed-method study on prevalence of recommended practices and related attitudes, beliefs, and other determinants | Note: this was a mixed method study with participants from the qualitative portion being drawn from the quantitative sample whose charactersitics were described as: “The majority of participants (72.5%) were 18–31 years old. The mean age of the most recent child was 11.4 months and the mean number of births was 2.5. Maternal educational status included (1) no formal education (18.4%); (2) completion of primary school (39.7%); and (3) completion of secondary school (37.1%). The most recent birth of most participants was attended by either a physician (39.4%) or a nurse (19.7%). The most recent births occurred in a public hospital (46.1%) or in a home (38.7%).” | Note: this was a mixed methods study. Only the qualitative results pertaining to this review are given here. From abstract: “Qualitative data revealed that dietary diversity may be low because (1) mothers often struggle to introduce complementary foods and (2) those that are traditionally introduced are not varied and primarily consist of grains and starches.” Additional notes: Qualitative data revealed several beliefs that may limit implementation of optimal IYCF practices. Women in some communities felt it was necessary to administer purgatives shortly after birth to cleanse the child’s body. A poor diet is believed to weaken breast milk, making it inadequate in terms of quality and/or unsatisfying to the child. Illness is thought to make breast milk “dirty” and unsafe for the child. In addition to these beliefs about breast milk, women view continued breastfeeding as a possible risk for infections among older children and thus prefer earlier weaning. Minimum dietary diversity achievement appears limited by difficulties mothers experience when complementary feedings and the low diversity of traditional, grain-based complementary feeding. | (2) (3) (4) (12) (19) (39) (51) (65) |

| 12 | Gretel H. Pelto, Margaret Armar-Klemesu Identifying interventions to help rural Kenyan mothers cope with food insecurity: results of a focused ethnographic study | Not stated | From abstract: “The results provide qualitative evidence about facilitators and constraints to IYC nutrition in the two geographical areas and document their inter-connections. We conclude with suggestions to consider 13 potential nutrition-sensitive interventions. The studies provide empirical ethnographic support for arguments concerning the importance of combining nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions through a multi-sectoral, integrated approach to improve the nutrition of infants and young children in low-income, resource-constrained populations.” Additional notes: Not having enough money to buy food was commonly reported as a challenge associated with caring for their children. Shortage of water/lack of access to clean water was also a difficulty, both in taking time from mothers in water retrieval and in limiting food preparation. Collecting firewood and food storage limitations were also reported as issues impacting food preparation for young children. Mothers knew the importance of food and nutrition to their child’s health and development. | (37) (39) (40) (41) (42) (43) (44) |

| 13 | Alessandra N Bazzano, Richard A Oberhelman, Kaitlin Storck Potts, Leah D Taub, Chivorn Var What health service support do families need for optimal breastfeeding? An in-depth exploration of young infant feeding practices in Cambodia | Mothers’ ages ranged from 21 to 55. The range of education attainment was between 0 and 16 years. Ten mothers were housewives. Other mothers worked as a factory worker (n = 4), farmer (n = 3), or, sewer/weaver (n = 4), The rest of mothers’ occupation included small convenience store worker, clothes seller, nighttime guard (father), and high school teacher. | From abstract: “The results revealed knowledge and practice gaps in behavior that likely contribute to breastfeeding barriers, particularly in the areas of infant latch, milk production, feeding frequency, and the use of breast milk substitutes. The predominant theme identified in the research was a dearth of detailed information, advice, and counseling for mothers beyond the message to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months.” Additional notes: Women knew to practice exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and reported following this behavior, however some mothers that reported this also said they used breastmilk substitutes on occasion. Some women described giving prelacteal feeds or waiting for the milk to come in prior to initiating breastfeeding. Some mothers gave water to newborns. Women reported that their own mothers, other female relatives or their midwives advised them on how to breastfeed. One mother reported that the midwife advised her to exclusively breastfeed but did not give her specific instructions to do so. Participants believed milk supply was related to the mother’s nutrition. Some felt they did not have enough milk and one was concerned about transferring illness to her newborn via breastmilk. Some felt that newborns required less milk or shorter feedings (or from just one breast) than older babies required. Some also did not want to rouse a sleepy newborn to feed. Many women had concerns that breastfeeding would impact their breast shape and size. They especially felt this could occur if they used both breasts during one feeding session. Positioning the newborn was also difficult for some mothers. Observations confirmed problems of poor latch, pain from suboptimal infant positioning and the practice of feeding from only one breast per session. | (1) (10) (11) (1) (19) (22) (25) (26) (28) (29) (33) (36) (37) (59) (62) (63) |

| 14 | Jennifer Burns, Jillian A. Emerson, Kimberly Amundson, Shannon Doocy, Laura E. Caulfield, Rolf D. W. Klemm A Qualitative Analysis of Barriers and Facilitators to Optimal Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding Practices in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo | The mean age of mothers was 25.8 years. Almost half of the mothers were literate (44%), however, around 28% had never attended school. Most of the mothers reported small businesses (47%) and agriculture (46%) as sources of income for their households. | From abstract: “Although breastfeeding was prevalent, few mothers engaged in optimal feeding practices. Barriers included poverty, high work burden, lack of decision-making power in the household, and perceived milk insufficiency. Health provider guidance and mothers’ motivation to breastfeed and feed nutrient-dense foods emerged as facilitators to optimal practices.” Additional notes: Many women recognized the benefits of colostrum for their newborn and gave it to them. Many said their mothers or grandmothers did not practice this and discarded the colostrum, but advice from health centers has changed this behavior. Common reasons for discontinuing exclusive breastfeeding included the feeling of insufficient milk, clogged milk duct, and the child being ill. These reason led to early introduction of complementary foods, water, or sugar water. The weather being hot was another reason cited for giving water to an infant less than 6 months old. Crying was considered an indication of the child being unsatisfied with breastmilk alone, so also led to early introduction of complementary foods like porridges. They were encouraged to continu this practice when giving other foods led to the baby stopping crying. Women who succeeded in exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months had encouragement during ANC visits. Mothers also reported that their own diets were important to the success of exclusive breastfeeding. Children’s diets (older than 6 months) have little diversity, and they eat what the family eats. Families with livestock do not tend to give the meat and milk available to their children as they prefer to sell these products in the market. The little meat the family eats is usually purchased, and milk is not commonly given to children as it is expensive. | (8) (10) (11) (18) (19) (22) (31) (32) (33) (36) (37) (39) (41) (45) (51) (63) (66) |

| Grey Literature | ||||

| 15 | Alive and Thrive-Ethiopia IYCF Practices, Beliefs, and Influences in Tigrey Region, Ethiopia | Not stated | From summary: “The findings from this study showed that although mothers have basic breastfeeding and complementary feeding information, visible gaps remain, such as not practicing exclusive breastfeeding, the existence of faulty traditional beliefs, and specific misconceptions about breastfeeding and complementary feeding. Among the major misconceptions is the belief of mothers that giving only breastmilk without adding fenugreek juice will expose the baby to intestinal worms. Beliefs also keep mothers from providing extra breastfeeding for a sick child. Some mothers reported the belief that encouraging suckling when the child is ill will only contribute to its illness. In Tigrey Region, mothers, community members, and HEWs alike stressed the unavailability of diverse foods and lack of resources to purchase foods as the major reasons for not following recommended complementary feeding practices. Lack of food was also mentioned in explaining why mothers introduce complementary foods later than 6 months of age, fail to offer children a variety of food types, and are unable to give children extra meals when they are sick or recovering from illness. The study identified misconceptions that affect complementary feeding habits. Mothers, community leaders, and even voluntary community health promoters (VCHPs) hold widespread beliefs that children cannot digest meat or other animal products, that children will choke on thick porridges, that extra food when a child is sick will contribute to illness, that children will refuse to eat during or after sickness, and that bottle feeding is more sanitary than using cups or hands to feed. Mothers and other community members, HEWs, VCHPs, and supervisors all expressed interest in learning about the recommended IYCF practices, as long as they trust that the person providing advice is properly trained and has reliable information. The findings from this study reveal that HEWs have reasonably better knowledge in the area of breastfeeding than in complementary feeding. Regarding their own knowledge and skills related to counseling, almost all of the HEWs are keen to improve those skills.” | (8) (20) (22) (33) (37) (39) (40) (41) (42) (48) (49) (50) (51) (53) (54) (55) (56) (57) (63) (65) (71) (72) (73) |

| 16 | Alive and Thrive IYCF Practices, Beliefs, and Influences in SNNP Region, Ethiopia | Not stated | From summary: This study indicates that breastfeeding is widely practiced in the research communities and is expected of all mothers and valued in the community for its contribution towards child growth and healthy development. Mothers in the study areas seem to know the expected breastfeeding requirements such as: on-demand feeding, frequency of breastfeeding, and the need to feed from both breasts. Yet exclusive breastfeeding is not widely practiced in the study communities. Mothers commonly introduce water, fenugreek, or linseed water as early as 2 months. In regards to complementary foods, the study indicates that the age for introduction of additional foods ranges from 2 months to 8 months, with a majority of mothers reporting that they had started giving foods at 6 months or earlier. Certain foods such as kale, enichila, banana, egg, pumpkin, carrot, and green vegetables are considered unsuitable and “too strong” for young children to digest before 1 year of age. Mothers consider meat in particular as too difficult to digest. Most mothers recommend meat for children above 1 or 2 years old. Mothers also expressed that they need to have a good income to buy or feed their children such foods. The study also revealed that HEWs feel they have a need to learn more about child feeding in order to effectively counsel mothers on IYCF. Several pointed out that they need more detailed information about additional foods, types of foods, and best approaches for preparing food for young children, with follow-up mechanism. | (5) (8) (10) (11) (18) (22) (27) (39) (41) (51) (52) (53) (55) (56) (62) (63) (65) (70) (71) (72) |

| 17 | United States Agency for International Development Formative assessment of infant and young child feeding practices at the community level in Zambia | Not stated | Breastfeeding is recognized as extremely important by mothers and other members of the community and remains the first choice for infant feeding. There is widespread awareness about the message of exclusive breastfeeding for six months, and generally mothers, fathers and grandmothers expressed their support for the practice. However, in reality many respondents expressed doubts as to whether breastmilk was really sufficient during the first six months and whether mothers could produce enough breastmilk to meet their child’s needs. In particular, families tended to introduce water before six months due to their perception that infants gesture to indicate their needs—and the belief that not responding is cruel to the child. And it is traditional to introduce water and watery foods early. When women are away from their infants, most respondents did not feel it was acceptable to express breastmilk. Many respondents strongly oppose it because it is considered untraditional, unhygienic, and unnecessary if the mother can stay close to her child. Multiple respondents commented that when mothers have an inadequate diet, they do not produce enough breastmilk, and need to introduce foods and liquids before 6 months of age, or must wean their child from breastmilk. The study identified a number of factors that represent barriers to the uptake of recommended infant and young child feeding practices. Respondents noted that cultural beliefs, traditions, and lack of knowledge about the nutritional needs of young children are barriers (e.g., most women give thin unenriched porridges as complementary foods). Many respondents identified lack of food and inability to afford food as a major reason for not providing appropriate foods to young children. Mothers did not cite grandmothers and fathers as important influencers of IYCF. The media was cited as a source of information on IYCF. | (8) (10) (11) (18) (19) (20) (22) (31) (32) (33) (34) (37) (39) (41) (62) (63) (65) |

| 18 | United States Agency for International Development Formative assessment of infant and young child feeding practices-federal capital territory, Nigeria | Not stated | Prelacteal feeding of water and sometimes water with herbs was widespread. There were different beliefs regarding colostrum but some believed (with influence by the grandmother) that it was bad and dangerous for the infant. A traditional practice is to give herbal infusions in water to treat and prevent illness, from the time of birth. Being away from baby inhibited breastfeeding, and often results in introduction of water. Many of the women are farmers and it is difficult to breastfeed when they are working on the farm. Breastmilk is not believed to be sufficient in either water or sustenance for babies 3 months and older, so thin gruels are introduced at this age. Some women believed that a mother with HIV could not breastfeed her baby. A sick child with a lack of appetite requires “forced feeding” but some felt concern that this might make the child choke (child sickness impacts child feeding). Maternal nutrition is recognized as important for pregnant and lactating women, and inadequate nutrition leads to inadequate milk production, but there was a lack of consensus of what foods are best for mothers and affordability may impact their ability to attain good foods. Fathers were supportive of the women and children achieving good nutrition by letting them eat first. | (7) (17) (18) (19) (20) (22) (27) (32) (33) (37) (47) (50) (62) (63) (65) (70) (72) (73) |

| 19 | United States Agency for International Development Consulting with caregivers–formative research to determine the barriers and facilitators to optimal infant and young child feeding in three regions of Malawi | Mothers in both phases were young, with more than half in each sample less than 25 years old. The overall literacy rate of the women in both samples (63.3 percent in Phase 1 and 69 percent in Phase 2) was slightly less than the national literacy average of 70 percent, 19 and in both samples, there was a wide variation in years of schooling, with approximately one-fifth to one-quarter of each group having no schooling at all and another quarter having more than six years of schooling. | Crying after feeding influenced the mother or other family members to give the baby other foods or liquids, assuming that the breastmilk was inadequate to satiate the baby’s hunger. Giving water during hot times of the year was thought to be necessary by some mothers, interfering with exclusive breastfeeding. Mothers did not know that breastmilk alone was acceptable for infants less than 6 months; once they were told this and tried it many were successful at transitioning to the improved practice. Observations identified two suboptimal breastfeeding practices: breastfeeds of very short duration, and breastfeeding from just one breast. When mothers transitions to improved practices, positive outcomes reinforced this behavior, including less crying and better sleep for babies, which give mothers more time for household chores, babies took more milk and did not have an upset stomach. Other family members support also facilitated good practice, for example by identifying that longer duration of breastfeeding indicated mother was showing more love to the child. Fear of HIV transmission was indicated as a reason for stopping continued breastfeeding early, along with having another pregnancy. The study also found that using breastfeeding to prevent pregnancy was also a facilitator of continued breastfeeding, but that mothers need counseling on the use of this method. Families given infants 6 to 8 months thin/watery porridges because they think this is the only food this age child can swallow and digest. | (8) (10) (11) (18) (21) (31) (34) (38) (41) (51) (53) (55) (63) (65) (66) (73) |

| 20 | Academy for Educational Development (AED)/ Alive and Thrive Ethiopia Country Office Initial Insight Mining and Pretest Research for Alive and Thrive Ethiopia | Not stated | Breastfeeding is common, but exclusive breastfeeding remains difficult for most mothers are they are responsible for a lot of work both in and out of the home. They are very busy and have limited access to information, do not have time to prepare special foods for children or exclusively breastfeed for six months (especially for mothers who work in the fields). Overall, there is a lack of awareness about nutritional requirements for infants and young children. Adding oil to baby food is common, and meat is considered healthy but not given to children under 2 years because it is thought babies cannot digest meat. Thick porridge is also considered to be hard to digest, so thin porridge is given to young children. Eggs are sold in the market rather than given to children because they are expensive; the same applies to milk—if they have a cow they sell the milk in market, and many cannot afford a cow or goat. There was a lack of awareness that different foods provided different nutrients, or that nutrition was related to mental and physical development. Respondents were not aware of the importance of the first two years of life. In most locations, there is lack of availability of several food categories, especially meat and fish, and they are expensive when they are available. | (14) (21) (22) (32) (33) (39) (41) (45) (51) (55) |

| 21 | United States Agency for International Development Engaging grandmothers and men in infant and young child feeing and maternal nutrition—Report of a formative assessment in Eastern and Western Kenya | Not stated | Although infant and young child care are considered primarily the mother’s realm, the study found that cultural beliefs also play an important role and grandmothers are largely responsible for propagating these beliefs. Grandmothers influence the early introduction of other foods, as a response to babies crying, indicating to them that breastmilk alone is insufficient. Feeding porridge to young babies also induces longer sleep sessions, which is a motivation for mothers to interrupt exclusive breastfeeding since it allows them to do more other activities. Some mothers’ negative connotation regarding exclusive breastfeeding was due to the perceptions that those who exclusively breastfed for 6 months were HIV positive. Reasons for early cessation of breastfeeding included pregnancy, doctor’s advice, baby refusing to eat other foods, and reduction in breastmilk supply. Mothers had minimal awareness of best complementary feeding practices. Resulting sub-optimal practices included early introduction of complementary foods, low quality foods in terms of energy and nutrient content, and inadequate feeding frequency. Foods given to young children are limited to what the household can afford (they eat modified family foods usually). Heavy workloads of the primary caregiver impacts complementary feeding behaviors. Force-feeding was reported as a common practice in Western Province. Some caregivers are only able to cook food, usually porridge, for the baby once a day and then store it in a flask the rest of the day, increasing the chance of bacterial growth. Grandmothers in Eastern Province believed that meat should not be given the children before 2 years of age, impacting the quality of diets of children. The study found that grandmothers and men have inadequate knowledge of recommended IYCF practices. Men listen to the advice of their mothers (the child’s grandmother) more than their wives regarding infant and childcare and feeding, since they are considered more experienced. Men may not be clear about their role in IYCF besides providing food. Men are interested in obtaining more information on IYCF but there are no forums to do so besides general community-level initiatives like flyers, radio programs, or messages from church. Men want to learn about best practices form trained experts, and trust those who they perceived as more knowledgeable on the topic. The majority of fathers did not believe exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months would be feasible due to the mother’s many responsibilities that require separation from the infant. Men agreed that they must provide mothers with adequate food to allow them to breastfeed successfully. Grandmothers are highly regarded as knowledgeable and experienced caretakers in the communities and so play a large role in infant and child caregiving and feeding. They also often provide financial support to their son’s young families. Grandmothers are the main alternative caregivers when mothers are away. They are also central in decision-making regarding food preparation and child feeding, along with other important activities like sick-child care. | (8) (10) (11) (16) (18) (19) (20) (21) (27) (33) (37) (39) (51) (58) (65) (71) (73) |

| 22 | United States Agency for International Development Ghana promotion of complementary feeding practices project—baseline survey report | The majority of respondents (42.2%) were between the ages of 22 and 29 years. The median age was 28 years. More than half of the respondents (56.3%) in the nine districts had little or no education (primary school or less). Only one-third had completed basic education (middle school or junior high school). District-specific data showed a similar result in only three of the districts: Sene, Sunyani West, and Kintampo South having respondents with tertiary level education. The majority were peasant farmers, including a few fishermen (55.2%); followed by petty traders (13.7%) and artisans (12.2%). A little more than 10% (11.5%) reported that they were unemployed. About 85% of the respondents were married. Only 7% of participants were single (never married), and 6.3% were cohabiting. The majority of the study participants reported Christianity as their religion (81.5%). This was followed by Islam (11.5%), with a small percentage being traditionalists. | Note: The majority of findings presented are from the quantitative portions of this study, so are not relevant for this review. Mothers and fathers who believed exclusive breastfeeding was good for baby < 6 months said that it helps a baby grow and protects them from breastfeeding. Those who did not believe exclusive breastfeeding was best said that this was because a baby needs more than just breastmilk to satisfy them (they also need water). | (18) (33) (65) (70) |

| 23 | Alive and Thrive Bangladesh Perceptions, practices, and promotion of infant and young child feeding—results and program implications of assessments in Bangladesh | Not stated | From summary: “Delayed initiation of breastfeeding, pre-lacteal feeding, and lack of exclusive breastfeeding were found to be common largely due to a lack of understanding of their importance and confusion about colostrum feeding as well as the definition of EBF. Also, mothers lack support for appropriate infant feeding after delivery. The perception that baby’s crying indicates insufficient breastmilk and that insufficient breastmilk is caused by poor maternal diets is widespread and a major barrier to EBF.” Additional notes: Perceptions of what foods should be given for complementary feeding of children 6 to 24 months differ from the recommended practices. There is a lack of diversity of type of food available to give children, especially animal sourced foods. Child’s poor appetite causes them to reject foods, inhibiting optimal feeding. Mother’s time constraints and lack of knowledge of appropriate complementary feeding were viewed as larger barriers than limited food availability. Mothers lack knowledge of how to make family foods appropriate for young babies and therefore do not give them meat because it is presumed to be not appropriate for them. | (10) (11) (19) (24) (39) (46) (48) (51) (55) |

Appendix C

| Finding No. | Review Finding | Studies Contributing to the Review Finding | Assessment of Methodological Limitations | Assessment of Relevance | Assessment of Coherence | Assessment of Adequacy | Overall CERQual Assessment of Confidence | Explanation of Judgement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | ||||||||

| Barriers to Recommended Breastfeeding | ||||||||

| Key Theme: Beliefs and Perceptions | ||||||||

| 1 | Breastfeeding deforms breasts | 1; 4; 13 | Minor methodological limitations (the authors do not clarify potential bias) | Minor concerns about relevance (the finding comes from studies in three settings across different locales: Cambodia, Dominican Republic, and Ghana) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | No concern about adequacy of data (the authors provide rich data) | High confidence | This finding was graded as high confidence because of few concerns about coherence and relevance and moderate methodological limitations. |

| 2 | Breastfeeding for more than one year makes children susceptible to infection | 11 | Minor methodological limitations (the authors do not state potential bias) | NA | NA | Minor concern about adequacy (the authors offer moderately rich data overall) | NA | NA |

| 3 | Breastmilk is bad because a mother is mad | 11 | Minor methodological limitations (the authors do not state potential bias) | NA | NA | Minor concern about adequacy (the authors offer moderately rich data overall) | NA | NA |

| 4 | Breastmilk is dirty because a mother has an illness | 11 | Minor methodological limitations (the authors do not state potential bias) | NA | NA | Minor concern about adequacy (the authors offer moderately rich data overall) | NA | NA |

| 5 | Breastmilk is not enough for a small baby | 8; 16 | Substantial methodological limitations (both studies do not explain the sampling method, eligibility criteria and potential bias) | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only two settings: Indonesia and Ethiopia) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Moderate concerns about adequacy (only two studies, one provides rich data, but the other one offers thin data) | Low confidence | This finding was graded as low confidence because of moderate concerns about relevance and adequacy of data and substantial methodological limitations. |

| 6 | When baby belches on the breast during breastfeeding the mother can develop swollen breasts | 4 | Moderate methodological limitations (the study does not state analysis methods and potential bias) | NA | NA | No concern about adequacy of data (the authors provide rich data) | NA | NA |

| 7 | Colostrum is not healthy for baby, so mothers discard colostrum | 3; 7; 10; 18 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies do not discuss potential bias; two studies do not state analysis methods; one does not say eligibility criteria) | Minor concerns about relevance (studies of breastfeeding from four countries: Ghana, Vietnam, Haiti and Nigeria) | Minor concerns about coherence (data reasonably consistent within and across all studies) | Minor concerns about adequacy (three studies offer rich data overall while one study shows thin data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns regarding relevance, coherence, and adequacy and moderate methodological limitations. |

| 8 | Baby remains hungry after breastfeeding (e.g., a baby is fussy even after breastfeeding) | 5; 6; 8; 9; 14; 15; 16; 17; 19; 21 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is applicable from four countries: Colombia, Ethiopia, Zambia and Kenya) | Minor concerns about coherence (data reasonably consistent within and across all studies) | Moderate concerns about adequacy (two studies provide rich data, but three studies offer only thin data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy of data and minor concerns about relevance and coherence. |

| 9 | Formula milk can make a baby healthier | 8 | Moderate methodological limitations (the authors do not explain the sampling method, eligibility criteria and potential bias) | NA | NA | No concern about adequacy (the authors provide rich data) | NA | NA |

| 10 | Mothers do not produce sufficient breastmilk | 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 13; 14; 16; 17; 19; 21; 23 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is universal in 13 countries: Cambodia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Colombia, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia, Laos PDR, Ethiopia, Zambia, Malawi, Kenya and Bangladesh) | Minor concerns about coherence (data reasonably consistent within and across all studies) | Minor concerns about adequacy (the majority of the studies provide rich data. Only one study offers thin data) | High confidence | This finding was graded as high confidence because of minor concerns about relevance, coherence and adequacy and moderate methodological limitations. |

| 11 | A baby is thirsty | 2; 7; 9; 13; 14; 16; 17; 19; 21; 23 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across nine countries: Cambodia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Vietnam, Lao PDR, Ethiopia, Zambia, Malawi, Kenya and Bangladesh) | Minor concerns about coherence (data reasonably consistent within and across all studies) | Moderate concerns about adequacy (six studies provide moderately rich data overall, but four studies offer thin data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy of data and minor concerns about relevance and coherence. |

| 12 | Purgative cleans a baby | 11 | Minor methodological limitations (the authors do not state potential bias) | NA | NA | Substantial concerns about adequacy (only short quotes are available) | NA | NA |

| 13 | Arrival of breastmilk is late | 3 | Moderate methodological limitations (the authors do not explain analysis methods and potential bias) | NA | NA | No concern about adequacy of data (the authors provide rich data) | NA | NA |

| 14 | Giving fenugreek and traditional herbs to newborns or young babies is a traditional practice | 20 | Moderate methodological limitations (the authors do not state sampling, analysis method and potential bias. | NA | NA | Minor concerns about adequacy (the authors offer only thin data) | NA | NA |

| 15 | Mothers do not have confidence in sufficient production of breast milk | 5 | Moderate methodological limitations (the authors do not state sampling and potential bias) | NA | NA | No concern about adequacy of data (the study provides rich data) | NA | NA |

| 16 | A baby still cries even after a mother breastfeeds | 21 | Moderate methodological limitations (the authors do not state sampling and potential bias) | NA | NA | No concern about adequacy of data (the authors provide rich data) | NA | NA |

| 17 | Herbal infusions in water prevents a baby from diseases. | 18 | Moderate methodological limitations (the authors do not state sampling and potential bias) | NA | NA | No concern about adequacy of data (the study shows rich data) | NA | NA |

| 18 | Traditional practices do not require exclusive breastfeeding (e.g., pre-lacteal feeds, giving water) | 2; 7; 14; 16; 17; 18; 19; 21; 22 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across nine countries: Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Vietnam, Ethiopia, Zambia, Nigeria, Malawi, Kenya and Ghana) | Moderate concerns about coherence (data in four studies lack a convincing explanation for the patterns found in these data while data in other five studies relatively are consistent within and across studies) | Moderate concerns about adequacy of data (three studies with thin data. Six studies with rich data). | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns about relevance and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and coherence and adequacy of data. |

| 19 | Mothers attribute their inability to produce enough breastmilk to not eating well | 11; 13; 14; 17; 18; 21; 23 | Moderate methodological limitations (five studies with moderate methodological limitations and one study with minor methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is universal in seven countries: Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia, Nigeria, Kenya, Haiti, Cambodia and Bangladesh) | Minor concerns about coherence (data reasonably consistent within and across all studies) | Minor concerns about adequacy of data (all data provides moderately rich data overall) | High confidence | This finding was graded as high confidence because of minor concerns about relevance, coherence and adequacy and moderate methodological limitations. |

| 20 | Pregnant women should not breastfeed (Mothers become pregnant before the child is 2 years old) | 15; 17; 18; 21 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across four countries: Ethiopia, Zambia, Nigeria and Kenya) | Minor concerns about coherence (data reasonably consistent within and across all studies) | Moderate concerns about adequacy of data (two studies offer relatively rich data, but other studies show only thin data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns about relevance, coherence and moderate concerns about methodological limitations and adequacy of data. |

| Key Theme: Lack of Support from Families, Health Workers (HWs) and Others | ||||||||

| 21 | Family members do not support mothers to breastfeed | 4; 19; 20; 21 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across four countries: Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and Ethiopia) | Minor concerns about coherence (data reasonably consistent within and across all studies) | Substantial concerns about adequacy (three studies provide poor data. Only one study offers rich data). | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns about coherence and relevance; moderate methodological limitations; and substantial concerns about adequacy. |

| 22 | Mothers do not have enough time to breastfeed their infants due to their work and short maternity leave | 4; 6; 7; 8; 9; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17; 18; 20 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across ten countries: Ghana, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Cambodia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Zambia and Nigeria) | Minor concerns about coherence (data reasonably consistent within and across all studies) | Moderate concerns about adequacy (the majority of the studies provide moderately rich data overall, but three studies offer thin data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns about relevance and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and coherence and adequacy of data. |

| 23 | HWs believe mothers do not produce enough breastmilk | 3 | Moderate methodological limitations (the authors do not explain analysis methods and potential bias) | NA | NA | No concern about adequacy of data (the authors provide rich data) | NA | NA |

| 24 | HWs do not have adequate knowledge and skills to help mothers | 2; 9; 23 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies have moderate methodological limitations) | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only two settings: Tanzania, Laos and Bangladesh) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Minor concerns about adequacy (all studies provide rich data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns about coherence and adequacy; moderate concern about relevance and methodological limitations. |

| 25 | Mothers do not receive any advice from HWs | 3; 9; 10; 13 | Minor methodological limitations (two studies with minor limitations and the other studies with moderate limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is universal across four countries: Ghana, Laos PDR, Haiti and Cambodia) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Minor concerns about adequacy (three studies provide rich data while only one study offers thin data) | High confidence | This finding was graded as high confidence because of few concerns about methodological limitations, relevance, coherence and adequacy. |

| 26 | Media has an impact on use of formula milk (and encourages it by instilling the belief that formula is healthy for baby) | 7; 8; 13 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies do not consider potential bias. One study do not describe sampling methods) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across three countries in Asia: Indonesia, Cambodia and Vietnam) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | No concern about adequacy of data (both studies offer rich data) | High confidence | This finding was graded as high confidence because of few concerns about coherence and relevance and moderate methodological limitations. |

| 27 | Traditional cultural beliefs of female family members (e.g., grandmothers) influence breastfeeding | 7; 16; 18; 21 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across four countries: Vietnam, Ethiopia, Kenya and Nigeria) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Moderate concerns about adequacy (two studies show poor data. The other studies provide moderately rich data overall) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns about coherence and relevance; moderate concern about methodological limitations and adequacy. |

| 28 | Suggestions from families, peers or close neighbors influence breastfeeding | 8; 9; 13 | Moderate methodological limitations (two studies do not consider potential bias. One does not state sampling. One does not explain analysis method) | Minor concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from three settings: Cambodia, Indonesia and Laos) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | No concern about adequacy of data (all studies offer rich data) | High confidence | This finding was graded as high confidence because of adequate data, minor concerns about coherence and relevance and moderate concerns about methodological limitations |

| Key Theme: Infant-Specific Factors | ||||||||

| 29 | A baby stops sucking milk | 9; 13 | Moderate methodological limitations (one study do not explain potential bias. The other one states response bias and does not explain analysis methods) | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only two settings: Cambodia and Laos) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | No concern about adequacy of data (both studies offer rich data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns about coherence, moderate concern about relevance and methodological limitations |

| 30 | Delayed breastfeeding initiation occurs with infants with respiratory problems | 10 | Minor methodological limitations (the study has some missing data) | NA | NA | No concern about adequacy of data (rich data) | NA | NA |

| 31 | Baby has a sickness | 4; 10; 14; 17; 19 | Moderate methodological limitations (the majority of the studies have moderate methodological limitations. Only one study has minor limitations. | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across five countries: Ghana, Haiti, Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria and Malawi) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Substantial concerns about adequacy (only one study offers rich data. Others show thin data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of substantial concerns about adequacy; moderate methodological limitations; and minor concerns regarding coherence and relevance. |

| Key Theme: Mothers’ Knowledge | ||||||||

| 32 | Mothers do not have knowledge about colostrum and breastfeeding initiation | 3; 7; 8; 14; 17; 18; 20 | Moderate methodological limitations (only one study with minor methodological limitations. Other studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across seven countries: Ghana, Vietnam, Indonesia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia, Nigeria and Ethiopia) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Substantial concerns about adequacy (only three studies provide moderately rich data overall. Others offer thin data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of substantial concerns about adequacy; moderate methodological limitations; and minor concerns regarding coherence and relevance |

| 33 | Mothers do not have knowledge about breastfeeding | 8; 9; 10; 13; 14; 15; 17; 18; 20; 21; 22 | Moderate methodological limitations (only one study with minor methodological limitations. Other studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across ten countries: Indonesia, Lao PDR, Haiti, Cambodia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya and Ghana) | Moderate concerns about coherence (three studies lack a convincing explanation. Data in other studies consistent within and across all studies) | Moderate concerns about adequacy (three studies provide poor data. Other studies offer moderately rich data overall) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of moderate concerns regarding methodology, coherence, adequacy and minor concerns about relevance. |

| 34 | Mothers do not recognize between baby feeding cues and behaviors | 8; 17; 19 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Moderate concerns about relevance (the review finding is found only in three settings: Indonesia, Zambia and Malawi) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Minor concerns about adequacy (all studies provide moderately rich data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of moderate concerns about methodology, relevance, coherence and minor concerns about adequacy. |

| 35 | Mothers do not have education | 2 | Moderate methodological limitations (the authors do not explain sampling and potential bias) | NA | NA | Minor concern about adequacy of data (the authors provide moderately rich data overall) | NA | NA |

| Key Theme: Mother-Specific Factors | ||||||||

| 36 | Mothers have breast and nipple problems | 4; 5; 7; 9; 13; 14 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across seven countries: Ghana, Colombia, Vietnam, Lao PDR, Cambodia and Democratic Republic of Congo) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Minor concern about adequacy of data (the majority of the studies provide moderately rich data overall, but one study shows only thin data) | High confidence | This finding was graded as high confidence because of minor concerns regarding relevance, coherence, adequacy and moderate methodological limitations. |

| 37 | Mothers have a sickness and/or died | 4; 9; 12; 13; 14; 15; 17; 18; 21 | Moderate methodological limitations (the most studies with moderate methodological limitations except one study with minor limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across seven countries: Ghana, Lao PDR, Kenya, Cambodia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Zambia, and Nigeria) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Substantial concerns about adequacy (only three studies show rich data, other studies provide only thin data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of substantial concerns about adequacy of data, moderate methodological limitations and minor concerns regarding relevance and coherence. |

| 38 | Breastfeeding initiation is delayed due to pregnancy induced hypertension and other complications after childbirth (performance of post-birth activities) | 3; 10; 19 | Minor methodological limitations (two studies with minor concerns and one study with moderate concerns) | Moderate concerns about relevance (the review finding is found in only three studies: Chana, Haiti and Malawi) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Substantial concerns about adequacy (all studies show poor data). | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of substantial concerns about adequacy, moderate concerns about relevance and minor concerns about coherence and methodological limitations. |

| Barriers to Complementary Feeding | ||||||||

| Key Theme: Food Security and Social and Cultural Factors | ||||||||

| 39 | Mothers and families do not have enough money to buy foods | 11; 12; 14; 15; 16; 17; 20; 21; 23 | Moderate methodological limitations (seven studies with moderate methodological limitations and one study with minor limitations) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across seven countries: Haiti, Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Zambia and Bangladesh) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Minor concerns about adequacy (all studies provide moderately rich data overall except one study with thin data) | High confidence | This finding was graded as high confidence because of minor concerns about relevance, coherence and adequacy; and moderate methodological limitations. |

| 40 | In periods of food insecurity, especially during drought, the purchase of higher quality foods are replaced with cheaper, less nourishing foods | 12; 15 | Moderate methodological limitations (both studies do not consider potential bias. One study does not state analysis methods). | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only two settings: Kenya and Ethiopia) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | No concern about adequacy of data (both studies provide rich data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns about coherence, moderate concern about relevance and methodological limitations |

| 41 | There are shortages of diverse foods to meet nutritional needs | 12; 14; 15; 16; 17; 19; 20 | Moderate methodological limitations (the majority of studies with moderate methodological limitations except with one study with minor concerns) | Minor concerns about relevance (the review finding is relevant across countries: Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Zambia and Malawi) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Minor concerns about adequacy (all studies provide moderately rich data overall) | High confidence | This finding was graded as high confidence because of minor concerns about relevance, coherence and adequacy; and moderate methodological limitations. |

| 42 | There is no piped water in the houses for cooking | 12; 15 | Moderate methodological limitations (both studies do not consider potential bias. One study does not state analysis methods). | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only two settings: Kenya and Ethiopia) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | No concern about adequacy of data (both studies provide rich data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns about coherence, moderate concern about relevance and methodological limitations |

| 43 | Some foods are only available seasonally | 12 | Minor methodological limitations (the authors do not clarify potential bias) | NA | NA | Minor concern about adequacy of data (the study offers moderately rich data overall) | NA | NA |

| 44 | Mothers prepare foods early in the day and then store it to give to their children later. | 12 | Minor methodological limitations (the authors do not clarify potential bias) | NA | NA | No concern about adequacy of data (the study provides rich data) | NA | NA |

| 45 | Mothers do not have financial decision-making power | 14; 20 | Moderate methodological limitations (both studies do not consider potential bias and analysis methods. One study does not describe sampling) | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only two settings: Democratic Republic of Congo and Ethiopia) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | No concern about adequacy of data (both studies offer rich data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor concerns about coherence, moderate concern about relevance and methodological limitations |

| Key Theme: Infant-Specific Factors | ||||||||

| 46 | Infants dislike animal source foods | 6; 23 | Moderate methodological limitations (both studies do not consider potential bias and analysis methods.) | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only one country: Bangladesh) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Substantial concern about adequacy (both studies provide thin data) | Low confidence | This finding was graded as low confidence because of moderate concerns about methodology and relevance; and substantial concerns about adequacy of data. |

| 47 | Infants do not have appetite to eat animal source foods | 6; 18 | Moderate methodological limitations (the authors in both studies do not consider potential bias. One study does not describe sampling. The other one does not explain analysis methods.) | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only two settings: Bangladesh and Nigeria) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | Moderate concern about adequacy (One study provides rich data. The other one offers only thin data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, adequacy of data, relevance and minor concerns about coherence. |

| 48 | Infants refuse to eat and or spit out of foods | 6; 15; 23 | Moderate methodological limitations (all studies with moderate methodological limitations) | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only two settings: Bangladesh and Ethiopia) | Moderate concern about coherence (data partially consistent within and across both studies) | Substantial concerns about adequacy (all studies offer thin data) | Low confidence | This finding was graded as low confidence because of moderate concerns about relevance and coherence and substantial concerns about adequacy of data and methodology. |

| 49 | Infants vomit when animal source foods are offered | 6; 15 | Substantial methodological limitations (the authors in both studies do not consider potential bias and analysis methods. One study does not describe sampling.) | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only two settings: Bangladesh and Ethiopia) | Moderate concern about coherence (data partially consistent within and across both studies) | Substantial concerns about adequacy (only two studies, both offering thin data) | Low confidence | This finding was graded as low confidence because of moderate concerns about relevance and coherence and substantial concerns about adequacy of data and methodology. |

| 50 | Infants have a sickness | 15; 18 | Moderate methodological limitations (the authors in both studies do not consider potential bias and analysis methods.) | Moderate concerns about relevance (partial relevance, as the studies were from only two settings: Nigeria and Ethiopia) | Minor concerns about coherence (data consistent within and across both studies) | No concern about adequacy of data (both studies offer rich data) | Moderate confidence | This finding was graded as moderate confidence because of moderate concerns about methods and methodology and minor concerns about coherence. |

| Key Theme: Family-Specific Actors | ||||||||