Investigation on the Effects of MXene and β-Nucleating Agent on the Crystallization Behavior of Isotactic Polypropylene

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.2.1. Synthesis of Ti3C2Tx

2.2.2. Synthesis of β-iPP/Ti3C2Tx Composites

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

2.3.2. Wide-Angle X-ray Diffraction

2.3.3. Polarized Light Optical Microscopy

2.3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.3.5. Transmission Electron Microscope

3. Results and Discussions

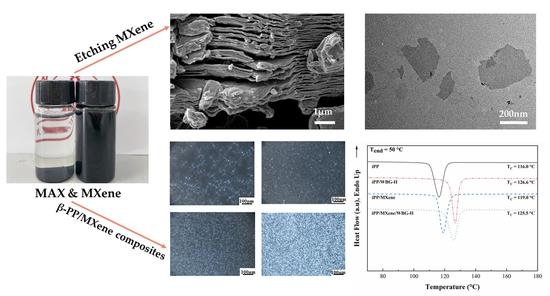

3.1. Structure and Morphology of MXene

3.2. Crystallization Behavior of β-iPP/MXene Composites

3.3. Melting Behavior of β-iPP/MXene Composites

3.4. WAXD Analysis

3.5. PLOM Observation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, S.; Wei, L.; Sun, J.; Huang, A.; Qin, S.; Luo, H.; Gao, C.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, J. Crystallization behavior and optical properties of isotactic polypropylene filled with α-nucleating agents of multilayered distribution. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krache, R.; Benavente, R.; López-Majada, J.; Perea, J.M.; Pérez, E. Competition between α, β, and γ Polymorphs in a β-Nucleated Metallocenic Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 6871–6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, X.; Fang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Kang, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M.; Li, L.; Sheng, X.; Hao, Z. Exploring the Effects of Stereo-Defect Distribution on Nonisothermal Crystallization and Melting Behavior of beta-Nucleated Isotactic Polypropylene/Graphene Oxide Composites. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 3020–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, R.; Xu, G.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, F.; Kang, J.; Xiang, M. Influence of L-lysine on the permeation and antifouling performance of polyamide thin film composite reverse osmosis membranes. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 25236–25247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruckner, S.; Meille, S.V.; Petraccone, V.; Pirozzi, B. Polymorphism in isotactic polypropylene. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1991, 16, 361–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, J. Supermolecular structure of isotactic polypropylene. J. Mater. Sci. 1992, 27, 2557–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, K.; Deng, H.; Fu, Q. Combined effect of β-nucleating agent and multi-walled carbon nanotubes on polymorphic composition and morphology of isotactic polypropylene. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2011, 107, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.; Piorkowska, E. Crystallization of isotactic polypropylene in a temperature gradient. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2001, 279, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, J.; Ji, F.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, G.; Shen, C. Effects of melt structure on shear-induced β-cylindrites of isotactic polypropylene. Polymer 2012, 53, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, X.; Yan, S.; Schultz, J.M. Initial Stage of iPP β to α Growth Transition Induced by Stepwise Crystallization. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 5062–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, J.; Mudra, I.; Ehrenstein, G.W. Highly active thermally stable β-nucleating agents for isotactic polypropylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 74, 2357–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, J. β-Modification of Isotactic Polypropylene: Preparation, Structure, Processing, Properties, and Application. J. Macromol. Sci. Part B 2007, 41, 1121–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Geng, C.; Wang, K.; Deng, H.; Chen, F.; Fu, Q.; Na, B. New Understanding in Tuning Toughness of β-Polypropylene: The Role of β-Nucleated Crystalline Morphology. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 9325–9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-W.; Yang, W.; Bao, R.-Y.; Wang, B.; Xie, B.-H.; Yang, M.-B. The enhanced nucleating ability of carbon nanotube-supported β-nucleating agent in isotactic polypropylene. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; He, J.; Chen, Z.; Yu, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, F.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M. Investigation on the crystallization behavior and polymorphic composition of isotactic polypropylene/multi-walled carbon nanotube composites nucleated with β-nucleating agent. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2014, 119, 1769–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Xin, Z. Nucleation characteristics of the α/β compounded nucleating agents and their influences on crystallization behavior and mechanical properties of isotactic polypropylene. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2010, 48, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, H.; Anayee, M.; Hantanasirisakul, K.; Shamsabadi, A.A.; Anasori, B.; Gogotsi, Y.; Soroush, M. Surface Modification of a MXene by an Aminosilane Coupling Agent. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 1902008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, M.; Kurtoglu, M.; Presser, V.; Lu, J.; Niu, J.; Heon, M.; Hultman, L.; Gogotsi, Y.; Barsoum, M.W. Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3 AlC2. Adv. Mater 2011, 23, 4248–4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verger, L.; Xu, C.; Natu, V.; Cheng, H.-M.; Ren, W.; Barsoum, M.W. Overview of the synthesis of MXenes and other ultrathin 2D transition metal carbides and nitrides. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2019, 23, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogotsi, Y.; Anasori, B. The Rise of MXenes. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 8491–8494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naguib, M.; Come, J.; Dyatkin, B.; Presser, V.; Taberna, P.-L.; Simon, P.; Barsoum, M.W.; Gogotsi, Y. MXene: A promising transition metal carbide anode for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 16, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verger, L.; Natu, V.; Carey, M.; Barsoum, M.W. MXenes: An Introduction of Their Synthesis, Select Properties, and Applications. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Ren, C.E.; Zhao, M.Q.; Yang, J.; Giammarco, J.M.; Qiu, J.; Barsoum, M.W.; Gogotsi, Y. Flexible and conductive MXene films and nanocomposites with high capacitance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16676–16681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, Q.; Li, P.; Zhou, A.; Cao, X.; Hu, Q. Preparation, mechanical and anti-friction performance of MXene/polymer composites. Mater. Des. 2016, 92, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Fu, L.; Yu, B.; Lv, Y.; Yang, F.; Song, P. Strengthening, toughing and thermally stable ultra-thin MXene nanosheets/polypropylene nanocomposites via nanoconfinement. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wu, M.; Zhou, A.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Wang, L. Non-isothermal crystallization and thermal degradation kinetics of MXene/linear low-density polyethylene nanocomposites. e-Polymers 2017, 17, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Hu, R.; Jiang, W.; Kang, J.; Xiang, M. Effects of MXene on Nonisothermal Crystallization Kinetics of Isotactic Polypropylene. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 19973–19982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wang, J.; Chen, D.; Liu, T.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, F.; Chen, J.; Kang, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M. Preparation and performance of a charge-mosaic nanofiltration membrane with novel salt concentration sensitivity for the separation of salts and dyes. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 595, 117472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Huang, X.; Song, X.; Kang, J.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, F.; Chen, J. Investigation on the Roles of β-Nucleating Agents in Crystallization and Polymorphic Behavior of Isotactic Polypropylene. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2020, 62, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xu, R.; Chen, J.; Kang, J.; Xiang, M.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Sheng, X. Ordered structure effects on β-nucleated isotactic polypropylene/graphene oxide composites with different thermal histories. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 19630–19640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, Y.; Zeng, F.; Chen, J.; Kang, J.; Yang, F.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M. Regulating polycrystalline behavior of the β-nucleated isotactic polypropylene/graphene oxide composites by melt memory effect. Polym. Compos. 2018, 40, E440–E448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zeng, F.; Chen, J.; Kang, J.; Yang, F.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M. Isothermal crystallization kinetics and subsequent melting behavior of β-nucleated isotactic polypropylene/graphene oxide composites with different ordered structure. Polym. Int. 2018, 67, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Chen, J.; Yang, F.; Kang, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M. Effects of Polypropylene Orientation on Mechanical and Heat Seal Properties of Polymer-Aluminum-Polymer Composite Films for Pouch Lithium-Ion Batteries. Materials 2018, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, Y.; Zeng, F.; Chen, J.; Kang, J.; Yang, F.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M. Effects of ordered structure on non-isothermal crystallization kinetics and subsequent melting behavior of β-nucleated isotactic polypropylene/graphene oxide composites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 136, 1667–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Weng, G.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Cao, Y.; Yang, F.; Xiang, M. New understanding in the influence of melt structure and β-nucleating agents on the polymorphic behavior of isotactic polypropylene. RSC Adv. 2014, 56, 29514–29526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Gai, J.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Peng, H.; Wang, B.; Cao, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, F.; et al. Dynamic crystallization and melting behavior of β-nucleated isotactic polypropylene polymerized with different Ziegler-Natta catalysts. J. Polym. Res. 2013, 20, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Song, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, M. Influences of Molecular Structure on the Non-Isothermal Crystallization Behavior of β-Nucleated Isotactic Polypropylene. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2020, 62, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; Du, S.; Guo, Y.C.; Zheng, N.; Wang, F.Y. Conditional Uncorrelation and Efficient Subset Selection in Sparse Regression. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, N.; Chen, B.; Chen, P.; Chen, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Xi, B. Multivariate Correlation Entropy and Law Discovery in Large Data Sets. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2018, 33, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.T.; Aizlewood, J.M.; Beckett, D.R. Crystalline Forms of Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 1964, 75, 134–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Chen, D.; Xiong, B.; Zheng, N.; Yang, F.; Xiang, M.; Zheng, Z. A facile route for the fabrication of polypropylene separators for lithium ion batteries with high elongation and strong puncture resistance. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 23135–23142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Jiang, W.; Song, X.; Kang, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M. Effects of Hyperbranched Polyester-Modified Carbon Nanotubes on the Crystallization Kinetics of Polylactic Acid. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 10362–10370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.; Xu, R.; Ye, L.; Xiong, B.; Kang, J.; Xiang, M.; Li, L.; Sheng, X.; Hao, Z. Effects of heat setting on the morphology and performances of polypropylene separator for lithium ion batteries. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 2217–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xiong, B.; Zeng, F.; Xu, R.; Yang, F.; Kang, J.; Xiang, M.; Li, L.; Sheng, X.; Hao, Z. Influences of Compression on the Mechanical Behavior and Electrochemical Performances of Separators for Lithium Ion Batteries. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 17142–17151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabeb, M.; Maleski, K.; Anasori, B.; Lelyukh, P.; Clark, L.; Sin, S.; Gogotsi, Y. Guidelines for Synthesis and Processing of Two-Dimensional Titanium Carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene). Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 7633–7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Sun, X.; Ma, Y. Accordion-like titanium carbide (MXene) with high crystallinity as fast intercalative anode for high-rate lithium-ion capacitors. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleski, K.; Ren, C.E.; Zhao, M.Q.; Anasori, B.; Gogotsi, Y. Size-Dependent Physical and Electrochemical Properties of Two-Dimensional MXene Flakes. ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 24491–24498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, W.; Shi, Y.; Yang, F.; Liu, M.; Chen, Z.; Yu, B.; Feng, Y. Creating MXene/reduced graphene oxide hybrid towards highly fire safe thermoplastic polyurethane nanocomposites. Compos. Part B 2020, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Tawiah, B.; Wang, L.Q.; Yin Yuen, A.C.; Zhang, Z.C.; Shen, L.L.; Lin, B.; Fei, B.; Yang, W.; Li, A.; et al. Interface decoration of exfoliated MXene ultra-thin nanosheets for fire and smoke suppressions of thermoplastic polyurethane elastomer. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 374, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillon, B.; Lotz, B.; Thierry, A.; Wittmann, J.C. Self-nucleation and enhanced nucleation of polymers. Definition of a convenient calorimetric “efficiency scale” and evaluation of nucleating additives in isotactic polypropylene (α phase). J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 1993, 31, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, J. Melting memory effect of the β-modification of polypropylene. J. Therm. Anal. 1986, 31, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, Z.; Sajo, I.E.; Stoll, K.; Menyhard, A.; Varga, J. The effect of molecular mass on the polymorphism and crystalline structure of isotactic polypropylene. eXPRESS Polym. Lett. 2010, 4, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, K.; Kressler, J.R.; Maier, R.D.; Scherble, J. Tailoring of the α-, β-, and γ-Modification in Isotactic Polypropene and Propene/Ethene Random Copolymers. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 8775–8780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Dong, Z.; Wang, K.; Wang, D. Morphological Characteristics of β-Nucleating Agents Governing the Formation of the Crystalline Structure of Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 6824–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Tm1 (°C) | Tm2 (°C) | Xc (%) | αc (%) | βc (%) | Xα (%) | Xβ (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPP | 162.8 | — | 41.4 | — | — | — | — |

| iPP/WBG-II | 163.4 | 150.9 | 44.6 | 27.7 | 72.3 | 12.4 | 20.0 |

| iPP/MXene | 161.9 | — | 43.0 | — | — | — | — |

| iPP/MXene/WBG-II | 164.7 | 151.4 | 41.4 | 35.3 | 64.7 | 14.6 | 22.8 |

| Parameters | Sample | (h k l) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α (110) | α (040) | α (130) | β (300) | ||

| 2θ (°) | iPP | 14.2 | 17.1 | 18.6 | — |

| iPP/WBG-II | 14.3 | 16.9 | 18.6 | 16.1 | |

| iPP/MXene | 14.1 | 16.9 | 18.6 | — | |

| iPP/MXene/WBG-II | 14.3 | 17.0 | 18.7 | 16.2 | |

| d-spacing (Å) | iPP | 6.2 | 5.2 | 4.8 | — |

| iPP/WBG-II | 6.2 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 5.5 | |

| iPP/MXene | 6.3 | 5.2 | 4.8 | — | |

| iPP/MXene/WBG-II | 6.2 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 5.5 | |

| FWHM | iPP | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.9 | — |

| iPP/WBG-II | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.3 | |

| iPP/MXene | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | — | |

| iPP/MXene/WBG-II | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | |

| L (nm) | iPP | 12.1 | 12.7 | 8.5 | — |

| iPP/WBG-II | 11.1 | 12.2 | 6.6 | 24.5 | |

| iPP/MXene | 16.1 | 20.5 | 17.7 | — | |

| iPP/MXene/WBG-II | 13.1 | 15.1 | 15.6 | 27.1 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, W.; Kang, J.; Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, B.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M. Investigation on the Effects of MXene and β-Nucleating Agent on the Crystallization Behavior of Isotactic Polypropylene. Polymers 2021, 13, 2931. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13172931

Peng W, Kang J, Song X, Zhang Y, Hu B, Cao Y, Xiang M. Investigation on the Effects of MXene and β-Nucleating Agent on the Crystallization Behavior of Isotactic Polypropylene. Polymers. 2021; 13(17):2931. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13172931

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Wanxin, Jian Kang, Xiuduo Song, Yue Zhang, Bo Hu, Ya Cao, and Ming Xiang. 2021. "Investigation on the Effects of MXene and β-Nucleating Agent on the Crystallization Behavior of Isotactic Polypropylene" Polymers 13, no. 17: 2931. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13172931

APA StylePeng, W., Kang, J., Song, X., Zhang, Y., Hu, B., Cao, Y., & Xiang, M. (2021). Investigation on the Effects of MXene and β-Nucleating Agent on the Crystallization Behavior of Isotactic Polypropylene. Polymers, 13(17), 2931. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13172931