Rural Women’s Invisible Work in Census and State Rural Development Plans: The Argentinean Patagonian Case

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Theory

2.3. Outcomes

2.3.1. Implications for the Recognition of Women Rural Work

2.3.2. Work and Implications for the Recognition of Family Farming

3. Results

3.1. The Patagonia, the Later Integration and the Sterility

3.2. The Measure of Work of Patagonian Women in Censuses’ History

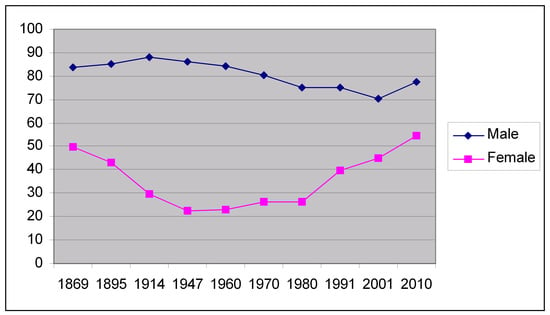

3.2.1. Historical Censuses

3.2.2. The Invisibility of Rural Patagonian Women

3.3. The Devaluation of Patagonian Production

3.3.1. The Thashumance Case

3.3.2. The Cherries Case

3.3.3. The actual Livestock Censuses Case

3.3.4. The Invisibility of Rural Female Work

3.4. Family Agriculture in Patagonian Land. The Permanence of the Denial of Women Work

3.4.1. The Problem of the Market as the Only Option

3.4.2. Idealization of Family Farming

3.4.3. Contributions from the Gender Perspective

3.4.4. Impact of These Processes on Public Policies and Academic Recognition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mellor, M. Ecofeminist Economics. Women Work Environ. 2002, 54, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chigbu, U.E. Anatomy of women’s landlessness in the patrilineal customary land tenure systems of sub-Saharan Africa and a policy pathway. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, M. Measuring women work: Methodological and conceptual issues in Latin America. Inst. Dev. Stud. Bull. 1984, 15, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iuorno, E.; Crespo, E. Nuevos Territorios, Nuevos Problemas; UNCo: Neuquén, Argentina, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez, P.; Lema, C.; Michel, C. La animalidad patagónica y la modernidad marginal. Tabula Rasa 2019, 32, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, P.; Lema, C. “Cipres, the triumphant”. The andean patagonian forest, the science, the moral and the social health in Argentina between late XIXth century and the ’30s decade. Asclepio 2019, 71, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, G.; Miranda, M. Evolución y revolución: Explicaciones biológicas y utopías sociales. In El Pensamiento Alternativo en la Argentina del Siglo XX: Identidad, Utopía, Integración (1900–1930); Biagini, H., Roig, A., Eds.; Biblos: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2004; pp. 403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Abramo, L. The Social Inequality Matrix in Latin America; United Nations ECLAC: Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, P. The “She-Land”, social consequences of the sexualized construction of landscape in North Patagonia. Gend. Place Cult. 2015, 22, 1445–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benería, L.; Feldman, S. Unequal Burden. Economic Crises, Persistent Poverty, and Women’s Work; Westview Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zusman, P. Prólogo. In Paisajes del Progreso: La Resignificación de la Patagonia Norte, 1880–1916; Navarro Floria, P., Ed.; EDUCO: Neuquén, Argentina, 2007; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nouaeillez, G. Patagonia as a borderland: Nature, culture and the idea of State. J. Lat. Am. Cult. Stud. 1999, 8, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sochen, J. Frontier women: A model for all women? S. D. Hist. 1976, 7, 36–56. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, P. Feminismo de frontera. La construcción de lo femenino en territorios de integración tardía. Rev. Fem. S 2018, 31, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puleo, A. Ecología y Género en Diálogo Interdisciplinar; Plaza y Valdés: Murcia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ramilo, D.; Prividera, G. La Agricultura Familiar en Argentina. Diferentes Abordajes Para su Estudio; Ediciones INTA: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Girbal Blancha, N. État, savoir, pouvoir et bureaucratie: Le déséquilibre régional agraire argentin 1880–1960. Économies Sociétés 2011, 44, 1601–1626. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, F. Viaje a la Patagonia Austral 1876–1877; Hachete: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ebelot, A. Introducción. In Informe Oficial de la Comisión Científica Agregada al Estado Mayor General de la Expedición al Rio Negro (Patagonia). Realizada en Los Meses de Abril, Mayo y Junio de 1879, Bajo las Órdenes del General, Julio, A. Roca; Entrega I—Zoología; Doering, A., Ed.; Imprenta de Osvaldo y Martínez: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1881; pp. VII–XXIV. [Google Scholar]

- Sarobe, J. La Patagonia y Sus Problemas. Estudio Geográfico, Económico, Político y Social de Los Territorios Nacionales del Sur; Aniceto López: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente, D. Primer Censo Argentino, 1869; Ministerio del Interior: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1872.

- De La Fuente, D. Segundo Censo de la República Argentina, 1895; Ministerio del Interior: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1898.

- Martínez, A. Tercer Censo Nacional. Levantado el 1° de junio de 1914; Ministerio del Interior: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1917.

- INDEC. Manual del Censista, Censo Nacional Agropecuario 2002; Ministerio del Interior: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2002.

- INDEC. Manual del Censista, Censo Nacional Agropecuario 2008; Ministerio del Interior: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008.

- INDEC. Cuestionario, Censo Nacional Agropecuario 2008; Ministerio del Interior: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008.

- Manzano, F. El mercado de Trabajo Femenino en Argentina. Evolución de Sus Principales Indicadores Desde el Año 1869 al 2010; XI Jornadas de Sociología: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Congress. Daily Sessions of the Congress of the Argentinean Nation, 1853–1904; National Government, Archivo General de la Nación: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1904.

- Daus, F. Trashumación de montaña en Neuquén. CONI 1947, 8, 383–426. [Google Scholar]

- Raone, J.M. Fortines del Desierto. Mojones de Civilización; Editorial Lito: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1969; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Silla, R. Identidad, intercambio y aventura en el Alto Neuquén. Intersecciones Antropología 2009, 10, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, C.; Núñez, P. Planificación y cambio en áreas rurales norpatagónicas. In Reconfiguraciones Territoriales e Identitarias. Miradas de la Historia Argentina Desde la Patagonia; Moroni, M., Funkner, M., Ledesma, L., Morales, E., Bacha, H., Eds.; Publicaciones UNLPam: Santa Rosa, Argentina, 2017; pp. 258–269. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, S. Procesos Psicosociales de Subjetivación en Experiencias Asociativas y Autogestivas Rurales. Casos Recientes en la Zona Andina y en la Línea sur Rionegrinas. Ph.D. Thesis, Socio-Community Psychology, Buenos Aires University, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cobelo, C. Transformaciones Territoriales en los Andes Patagónicos. El Caso de las Zonas Rurales de El Bolsón, Río Negro. Ph.D. Thesis, Agricultural Sciences, Buenos Aires University, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Valtriani, A. Modelos de Desarrollo Forestal, sus Conflictos y Perspectivas en el Sector de Mirco Pymes Forestales; Estudios de Caso en la Región Noreste y Centro de la Provincia de Chubut. Ph.D. Thesis, Economic Sciences, Buenos Aires University, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Méndes, J. Sociedades del Bosque. Espacio Social, Complejidad Ambiental y Perspectiva Histórica en la Patagonia Andina Durante los Siglos XIX y XX. Master’s Thesis, Social Sciences, CLACSO, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Danklmaier, C.; Wienke, H.; Riveros, H. Activación Territorial con Enfoque de Sistemas Agroalimentarios Localizados (AT-SIAL); IICA: El Bolson, Argentina, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coronato, F.; Fasioli, E.; Scheitzer, A.; Tourrand, J. Rethinking the role of sheep in the local development of Patagonia, Argentina. REMVT Revue D’élevage et de Médecine Vétérinaire des pays Tropicaux 2016, 68, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López, S. El INTA Bariloche. Una Historia con Enfoque Regional; UNRN Editorial: Viedma, Argentina, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Biaggi, C.; Canevari, C.; Tasso, A. Mujeres que Trabajan la Tierra. Un Estudio Sobre las Mujeres Rurales Argentinas; Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería Pesca y Alimentos: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Papuccio, S. Mujeres, Naturaleza y Soberanía Alimentaria; Librería de Mujeres Editoras: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Siliprandi, E.; Zuluaga, G. Género, Agroecología y Soberanía Alimentaria. Perspectivas Ecofeministas; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Siempre Vivas. Las Mujeres en la Construcción de la Economía Solidaria y la Agroecología. Textos Para la Acción Feminista; SOF-Fundación Heinrich Böll Cono Sur: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira, M.; Urcola, M. La jerarquización de la agricultura familiar en las políticas de desarrollo rural en Argentina y Brasil (1990–2011). Rev. Ideas 2013, 7, 96–137. [Google Scholar]

- Feito, M. Agricultura familiar para el desarrollo rural argentino. Avá 2013, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Carrapizo, V.; Speranza, M.; Ganduglia, F. Nos Juntamos? Facilitando Procesos Asociativos a Partir de las Experiencias de la Agricultura Familiar; IICA-INTA-Min, De agricultura: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Muzi, E. Atlas de la Población y la Agricultura Familiar en la Región Patagonia; INTA: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Trpin, V.; Rodriguez, M.; Brouchoud, S. Desafíos en el abordaje del trabajo rural en el norte de la Patagonia: Mujeres en forestación, horticultura y fruticultura. Trab. Y Soc. 2016, 28, 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, S. Mujeres Artesanas y Sentidos que Hilan su Quehacer en Prácticas Cooperativas. La Experiencia de la Cooperativa Artesanal Zuem Mapuche (Río Negro, Argentina). Ph.D. Thesis, Psychology, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Raguileo, D. Trayectoria Socio-Ecológica en Valles Bajo Riego: El Caso de Sarmiento en la Provincia de Chubut. Master’s Thesis, Producción de Rumiantes Menores, Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Universidad Nacional De Rosario & INTA, Bariloche, Argentina, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, L. The baby and the bath water: Diversity, deconstruction and feminist theory in geography. Geoforum 1991, 22, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzegwu, N.; Bockover, M.; Femenias, M.; Chaudhuri, M. How (if at all) is gender relevant to comparative philosophy? J. World Philos. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N. Caste, kinship, and life course: Rethinking women’s work and agency in rural South India. Fem. Econ. 2014, 20, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agarwal, B. Are We Not Peasants Too? Land Rights and Women’s Claims in India; The Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, B. Gender and land rights revisited: Exploring new prospects via the state, family and market. J. Agrar. 2003, 3, 184–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydar, G. Sexualised productions of space. Gend. Place Cult. 2012, 19, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, V. Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development; North Atlantic Books: Berkley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, V. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Madden, E. Irish Studies: Geographies and Genders; Cambridge Scholars Publication: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.; Simpson, R. Hakim revisited: Preference, choice and the postfeminist gender regime. Gend. Work Organ. 2017, 24, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, A.; Lewis, P.; Ozkazanc-Pan, B. A critical moment: 25 years of gender, work and organization. Gend. Work Organ. 2019, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferraro, F.; Pfeffer, J.; Sutton, R. How and why theories matter: A comment on Felin and Foss. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Femenías, M.L. Itinerarios de la Teoría Feminista y de Género. Algunas Cuestiones Histórico-Conceptuales; Universidad Nacional de Quilmes: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Svampa, M.; Viale, E. Maldesarrollo. La Argentina del Extractivismo y el Despojo; Katz Conocimiento: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Balibar, E. Violencias, Identidades y Civilidad; Editores Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barrancos, D. Gender and citizenship in Argentina. Iberoam. Nord. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Stud. 2011, XLI, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Barrancos, D. La puñalada de Amelia (o cómo se extinguió la discriminación de las mujeres casadas del servicio telefónico en la Argentina). Trabajos y Comunicaciones 2008, 8, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.; Mills, S. Feminist Postcolonial Theory. A reader; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sourisseau, J. Las Agriculturas Familiares y los Mundos del Futuro; IICA-AFD: San José, Costa Rica, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guereña, A. Unearthed: Land, Power and Inequality in Latin America; OXFAM International: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- López, E.V. El Movimiento Feminista. Tesis Presentada Para Optar por el Grado de Doctora en Filosofía y Letras; Facultad de Filosofía y Letras-Imprenta Mariano Moreno: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Femenías, M. Notas acerca de un debate en América del sur sobre la dicotomía «feminismo: ¿Igualdad o diferencia?». Feminismo/S 2010, 15, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abarzua, F.; di Nicolo, C. Extractivismo en territorio del norte de la Patagonia. Frutihorticultura en los valles de Río Negro y turismo en Villa Pehenia-Moquehue, Neuquén. Rev. Del Dep. Geogr. UNC 2018, 6, 18–345. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, P.; Michel, C. Territorios conquistados y trabajos invisibles. Las mujeres en el ordenamiento territorial patagónico. Pilquén 2019, 22, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. Feminist Theory from Margin to Center; South End Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Easdale, M.H.; Rosso, H. Dealing with drought: Social implications of different smallholder survival strategies in semi-arid rangelands of Northern Patagonia, Argentina. Rangel. J. 2010, 32, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcuy Ameghino, E. La cuestión agraria en Argentina. Caracterización, problemas y propuestas. Revista Interdisciplinaria Estudios Agrarios 2016, 45, 5–50. [Google Scholar]

- Barsky, O.; Posada, M.; Barsky, A. El Pensamiento Agrario Argentino; CEAL: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, D. Facundo ó Civilización I Barbarie en las Pampas Argentinas; Hachette: Paris, France, 1874. [Google Scholar]

- Lema, C.; Núñez, P. Destruir para desarrollar. El rol de cienc. en la desigual. Del ordenamiento patagónico. Cuadernos de Geografía: Revista Colombiana de Geografía 2019, 28, 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Broguet, J.; Corvalán, M.; Drenkard, P.; Mennelli, Y.; Rodriguez, M. Argentina, where are you from? Performative and pedagogical strategies to tackle racism. Revista Brasileira de Estudos da Presença 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hull, G.; Scott, P.; Smith, B. All the Women Are White, All Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave; The Feminist Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam, A. Black feminist perspective on the sexual commodification of women in the new global culture. In Black Feminist Antropology. Theory, Politics, Praxis and Poetics; McClaurin, I., Ed.; Rutgers University Press: Utopia, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 150–170. [Google Scholar]

- Neely, B.; Samura, M. Social geographies of race: Connecting race and space. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2011, 34, 1933–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, V. Ciudadanía universal/derechos excluyentes. La mujer según el Código Civil en Argentina, Brasil y Uruguay (c. 1900–1930). E-l@tina 2003, 1, 10–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, K. Cultures of economies: Gender and socio-spatial change in Nepal. Gend. Place Cult. 2003, 10, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, M. Landscaping Patagonia: A Spatial History on Nation-Making in the Northern Patagonian Andes, 1895–1945. Ph.D. Thesis, History, Emory University, Atlanta, GE, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau, D. Maps, numbers, text, and context: Mixing methods in feminist political ecology. Prof. Geogr. 1995, 47, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, J.M. Los Censos históricos como fuente para el estudio de la participación femenina en el mercado. El caso de la provincia de Mendoza a comienzos del siglo XX. Mora 2009, 15, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Quay Hutchinson, E. La historia detrás de las cifras: La evolución del censo chileno y la representación del trabajo femenino, 1895–1930. Historia 2000, 33, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, C. Institucionalización del desarrollo territorial en la región de la Norpatagonia: Una mirada desde lo rural. In Araucanía-Norpatagonia II: La fluidez, lo Disruptivo y el Sentido de la Frontera; Núñez, N., Ed.; UNRN Ed: Viedma, Argentina, 2017; pp. 264–284. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, S.; Núñez, P. La violencia del silencio, las mujeres de la estepa. Revista Polémicas Feministas 2013, 2, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gras, C. Changing patterns in family farming: The case of the pampa region, Argentina. J. Agrar. Chang. 2009, 9, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, P.; López, S. The North Patagonia territorialization, the Río Negro case in the second half of twenty century. Cuad. Geográficos 2015, 54, 38–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lanari, M.; Reising, C.; Monzón, M.; Subiabre, M.; Killmeate, R.; Basualdo, A.; Cumilaf, A.; Zubizarreta, J. Recuperación de la oveja linca en la patagonia Argentina. Revista Aica 2012, 2, 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Femenías, M. ‘How (if at all) is gender relevant to comparative philosophy?’ A response to Nzegwu. J. World Philos. 2016, 1, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lattuada, M. Políticas de desarrollo rural en la Argentina. Conceptos, contexto y transformaciones. Temas Y Debates 2014, 27, 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, C.; Núñez, P. La globalización en la norpatagonia andina desde la agricultura familiar. Rev. Austral Cienc. Soc. 2020, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Debenedetti, S.; Acebal, M.; Abad, M.; Rosso, H.; Suarez, A. Patagonian mohair: Angora goat production in a really harsh environment. Angora Goat Mohair J. 2010, 52, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Flores, L. El enfoque de género y el desarrollo rural: ¿Necesidad o moda? Revista Mexicana Ciencias Agrícolas 2015, 1, 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo, F.; Blanco, V. Guía Práctica Para Técnicos y Técnicas Rurales el Desarrollo Rural Desde el Enfoque de Género; Ministerio de Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014.

- Paz, R. Agricultura familiar y sus principales dimensiones: La pampeanización del término. Revista Interdisciplinaria Estudios Agrarios 2014, 41, 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Civitaresi, M.; Colino, E.; Landriscini, G. Territorios en Transformación en la Norpatagonia. Análisis Comparado del Impacto de Procesos Globales en Ciudades Intermedias; I Congreso Internacional De Geografía De La Patagonia Argentino-Chilena; Comahue National University: Neuquén, Argentina, September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavoni, G. Describir y prescribir: La tipificación de la agricultura familiar en la Argentina. In La Agricultura Familiar del MERCOSUR. Trayectorias, Amenazas y Desafíos; Manzanal, M., Neiman, G., Eds.; Ciccus: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2010; pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, D. Territorialidades campesinas entre lo heterónomo y lo disidente: Formas de gestión de la producción y tenencia de la tierra en el campo argentino. Política Trabalho Revista Ciências Sociais 2016, 45, 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Galer, A.; Manavella, F.; Bottaro, H.; San Martino, L.; Casiraghi, L. Aportes al Desarrollo Rural en Patagonia Sur; INTA: Trelew, Argentina, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle, H. Patagonian soils: A regional synthesis. Ecol. Austral 1998, 8, 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos, M.; Carrera, A.; Bertiller, M.; Olivera, N. Grazing enhanced spatial heterogeneity of soil dehydrogenase activity in arid shrublands of Patagonia, Argentina. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagra, E. Does Product Diversification Lead to Sustainable Development of Smallholder Production Systems in PATAGONIA, Northern Argentina? Cuvilier Verlag: Göttingen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Conterno, C. La extensión rural del INTA con la comunidad Nehuen-CO, El Chaiful. Nuevas experiencias de trabajo comunitario junto a INTA Jacobacci. Presencia 2017, 5, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Núñez, P.G.; Michel, C.L.; Leal Tejeda, P.A.; Núñez, M.A. Rural Women’s Invisible Work in Census and State Rural Development Plans: The Argentinean Patagonian Case. Land 2020, 9, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9030092

Núñez PG, Michel CL, Leal Tejeda PA, Núñez MA. Rural Women’s Invisible Work in Census and State Rural Development Plans: The Argentinean Patagonian Case. Land. 2020; 9(3):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9030092

Chicago/Turabian StyleNúñez, Paula Gabriela, Carolina Lara Michel, Paula Alejandra Leal Tejeda, and Martín Andrés Núñez. 2020. "Rural Women’s Invisible Work in Census and State Rural Development Plans: The Argentinean Patagonian Case" Land 9, no. 3: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9030092

APA StyleNúñez, P. G., Michel, C. L., Leal Tejeda, P. A., & Núñez, M. A. (2020). Rural Women’s Invisible Work in Census and State Rural Development Plans: The Argentinean Patagonian Case. Land, 9(3), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9030092