1. Introduction

Finding a place to live is one of the biggest and most important decisions in life. People who are faced with the choice of owning or renting a home do not find the decision easy [

1]. This is because they have to choose between alternatives with very different costs/characteristics; essentially, it is a routine decision made under uncertain conditions. Before such decisions are made, several scenarios are usually run, in which appropriate assumptions are made about the elements affecting the value of the property in the future (e.g., the risk of depreciation, etc.), and its financing (i.e., the creditworthiness of the buyer), as well as the living situation of the parties involved [

2]. In summary, individuals or entire households face an extremely serious problem, which from their point of view consists of making important decisions under uncertain conditions. While renting an apartment or house involves recurring low costs in the form of rent payments and offers some decision flexibility due to low barriers to entry and exit, owning requires a high one-time initial investment that comes with much less decision flexibility. Aside from the financial aspects (i.e., whether or not one can afford to own a home), preference in this regard may depend on the expected duration of use of the home itself. Home ownership may be preferable for long-term use, while for short-term use, renting a house is usually considered the better option for obvious reasons. For example, Hargreaves [

3] has shown that people generally prefer homeownership to renting when the assumed useful life is more than 3 years. However, there is a caveat: this applies when the rate of appreciation of real estate is higher than the rate of inflation. A higher interest rate on the borrowed capital increases the time needed to break even [

3]. This topic gains importance against the backdrop of the current cycle of significant interest rate hikes and the politics of dear money. More importantly, the problem is that the duration of housing use is usually not known in advance and may depend on a whole range of different factors [

2]. In our daily lives, there are events that can completely change our previous decisions, including those related to owning or renting an apartment or house. One example is the coronavirus pandemic. Another example is the current, very disturbing, and unexpected increase in inflation and the deterioration of living conditions.

There is a general view that renting is a reasonable alternative to homeownership. Erbel [

4], for example, discourages young adults from buying a house, arguing that homeownership usually hinders mobility (i.e., geographic and occupational mobility), even though globalization has opened up the world and one can now work anywhere on the globe. Beugnot et al. [

5] argue that homeownership impedes mobility because it limits job searches in the economy and imposes additional costs associated with relocation (when a job is far away). However, it is worth considering whether renting from the perspective of young adults is a trend resulting from new trends and preferences that are unique to them, or whether it is an economic necessity that is a consequence of the low incomes of young people who cannot afford homeownership and therefore opt for affordable rental housing. Data show that 45.1% of young adults aged 25–34 still live with their parents, which is probably not their preferred situation and is an undesirable phenomenon from a sociological perspective [

6]. Thus, it is worth looking for a rationale for this phenomenon, i.e., for the fact that a large group of young people do not rent an apartment, but continue to live with their parents. It is quite possible that the total cost of rent is too high for them. On the other hand, if rent payments are almost as high as the cost of a mortgage, the renters might consider owning their own apartment or house. So why do they not? To understand the behavior of young adults in the housing market in its complex socioeconomic context, both now and in the future, it will be extremely important to examine many similar issues and answer a whole series of questions. These questions should address the following areas: housing preferences in the context of economic and socio-cultural conditions, lifestyle, utility analysis, etc. It is also worth seeking answers to the question of whether the existing 30-year mortgage annuity (i.e., a repayment mortgage) is attractive enough to the cohort of renters expressing a need for homeownership to encourage them to purchase a home. Perhaps, from the banking sector’s perspective, it is possible to offer borrowers a more attractive loan package that is tailored to their income level, occupational status, etc.

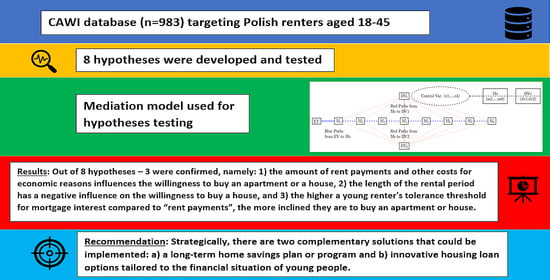

The aim of this study is to analyze the main factors influencing the housing preferences of young adults in Poland, focusing on the analysis of the preferences of those who have already rented an apartment or a house. Using a customized questionnaire survey and a mediation model, the study provides insights into the Polish housing market and analyzes the motivations of young Polish renters. It identifies a range of factors that influence their decisions and choices. The study targets young adults between the ages of 25 and 45. It analyzes their attitudes and their ability and willingness to buy an apartment or house financed with a mortgage loan. Housing is a popular topic of public debate in Poland, but most of it is conducted online or as a commercial initiative of the private sector (mostly developers) [

7,

8]. On the other hand, there is a lack of solid academic research on the cognitions of young renters in Poland. The present study is an attempt to fill this gap.

The structure of the study is very simple.

Section 2 discusses previous empirical findings and relevant theoretical concepts.

Section 3 outlines the analytical framework, data collection methods and mediation model, including descriptive statistics and methodology.

Section 4 provides a detailed presentation of the results, followed by a discussion in

Section 5. Finally, conclusions from the conducted research are drawn and presented in

Section 6.

2. Empirical Evidence

The importance of home ownership and housing studies has been repeatedly addressed in the literature, and there are numerous studies on the subject [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Problems have been increasing for years, but in recent years, housing problems among young adults have increased particularly markedly in many countries [

14,

16]. A wide range of factors have been found to influence young people’s housing decisions [

17,

18]. There are studies that show that among the various factors that influence this market, economic factors are the most important [

19]; they have a greater influence on housing choices than, for example, social, or cultural factors. Economic factors include factors such as housing prices, income and wealth, and interest rates, but also factors such as tax regulations influenced by state governments [

20,

21]. In turn, other studies point to the significant influence of inflation factors and, in particular, the relevance of the relationship between homeownership and inflation [

22]. There are also quite a number of studies that point to the significant social [

11] and economic benefits of homeownership compared to renting [

9,

12,

13,

15,

23,

24]. Among the benefits, researchers list better social outcomes [

11,

12], greater civic awareness [

9,

13,

15], less crime and fewer so-called pathological incidents [

23], and better cognitive and behavioral performance and learning outcomes [

12]. Homeownership creates the right conditions to support and encourage families [

24]. In addition, easy access to homeownership leads to higher birth rates [

25]. Moreover, homeownership leads to significantly higher life satisfaction [

24,

26]. Higher homeownership rates are also generally associated with higher housing prices [

11].

People’s attitudes toward housing choice are also influenced by certain economic, political, and cultural dimensions of consumption, where countries differ [

27]. Nevertheless, positive or negative attitudes toward homeownership are also significantly influenced by the socialization process [

1], which is why some researchers point out the urgent need for numerous debates and information campaigns on this topic [

27]. It is obvious that there is a significant relationship between socialization and public information campaigns. Such campaigns are later reflected in appropriate public housing policies and form the basis for public debates [

27]. It is important to note when considering the preferred form of housing that ownership has generally been preferred to renting so far, unless there are financial constraints (i.e., assuming that a person facing this type of choice can afford both) [

16]. For example, one study showed that Americans prefer homeownership [

15]. More specifically, 86% of respondents clearly preferred homeownership to renting. Only 26% of respondents said they chose to rent their apartments due to pure conviction rather than for financial reasons.

As for the topic of housing preferences, one cannot avoid addressing housing markets (since these issues are inextricably linked). In this issue, speculation and occasional collapses of housing bubbles play an important role, reflected in market conditions and, in particular, in economic uncertainties and difficulties in accessing mortgage financing [

8]. This is exactly how the situation looked for a while after the sub-crisis more than a decade ago, and most importantly, the general uncertainty spilled over to the whole world, including Poland [

10,

28]. This is important because in the post-crisis period, people are generally less likely to opt for home ownership [

10]. It is important to note that the crisis hit mainly the countries where the share of the construction sector in GDP is the highest [

29], such as Spain [

30]. Consequently, the shock of the crisis hit young Spaniards the hardest and led to a significant increase in their interest in renting compared to homeownership [

30]. This is a dangerous phenomenon, since it affects socioeconomic aspects and issues of human identity and subjectivity, as well as the tendency of young people to start a family and their emancipation [

31]. If such a situation persists over the long term and is accompanied by changes in young people’s norms and aspirations (and this is often the case), the social impact of such cohabitation could be difficult to manage. The countries most vulnerable to severe social changes are those where the crisis could not be contained relatively quickly, disrupting previously prevalent living arrangements, and where the living conditions and lifestyles of young adults have been forced in some way, intentionally or unintentionally.

A number of studies also point to another phenomenon: namely that for many young adults the alternative to buying their own home is no longer renting, but having to share housing with their parents, which significantly deteriorates their emancipatory abilities [

7,

20,

32] and also affects the quality of their social life [

30,

31,

33]. Thus, young people today start their own families much later, which is of course significantly influenced by the lack of their own housing [

16,

32]. Unfortunately, the truth is that no previous generation has lived with their parents as long as today’s [

16,

32]. In this context, it is worth considering the example of Spain, which is traditionally considered a pro-ownership society when it comes to the choice of housing. The great financial crisis in the first decade of this century completely disrupted social expectations and aspirations regarding choices in this area. The difficult situation of young adults means that their parents play a greater role [

20,

30,

31,

33,

34], whether through financial transfers (donations) and loans or in-kind contributions. Housing preferences are therefore increasingly determined by the social and socioeconomic class of young adults’ parents. In this context, it should also be mentioned that parents of young adults exercise a kind of control over their children who are recipients of housing capital, which manifests itself in influencing their standardized social and economic choices [

35]. It is also important to point out that the importance of parents’ material status increases as housing prices continue to rise and affordability decreases [

33,

34]. In particular, the problem of the importance of parental support factors is beginning to affect women more [

34].

Precisely because of the pervasive market and social uncertainty [

16,

36], the perspective changes when it comes to financial burdens of any kind. The way rent is viewed is also changing. Increasing uncertainty and more frequent black swan events lead to increased risk aversion, which leads to increasing interest in rent [

16]. It is certainly the case that the option to rent gives people a greater sense of flexibility, as it offers the possibility of moving out at any time, which in the context of many economic uncertainties (binary events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the potential collapse of many businesses, and the possibility of losing one’s job) provides a sense of greater security. The lack of access to housing for young adults leads to unequal housing conditions, lower social participation, and an increasingly visible wealth gap between generations. According to Willetts, the older generations have benefited from an exceptional situation, but it has and will burden the welfare of the younger generations, which is unfair [

37]. According to the author, the demographic boomers not only dominate culturally through their power as an extremely large consumer market, but have also amassed huge amounts of wealth and real estate, all at the expense of younger generations. The phenomenon of the wealth gap between generations is most likely to be observed in the markets with the highest prices and the lowest prices, where the opportunities to buy a house are rather limited [

34]. The housing status of young adults is also strongly influenced by government social policies [

20], as evidenced by relevant research showing a negative impact of government benefits on attitudes toward homeownership [

20]. Cultural differences also play an important role. Where these values are closer to family values, and where the household is seen as a certain symbol of security and refuge, the level of homeownership tends to be higher (see

Figure 1).

Figure 1 shows some structural and systemic differences between countries that are not directly related to the economy and that are reflected in the popularity of homeownership. In Hungary, Slovakia, or Spain, for example, home ownership is generally considered better than in Germany or Austria, which are richer in terms of GDP per capita [

22].

The differences in attitudes among people in different countries are due to non-price aspects, which include demographic factors, institutional conditions, government housing policies [

20], cultural differences, etc., in addition to purely economic factors related to prices and supply [

2,

22]. Decisions about the preferred housing type may be related to lifestyle [

16] or, for example, to a particular cultural background and heritage. From a purely economic perspective, housing type is determined by housing prices themselves (so-called affordability) [

38], inflation [

22], uncertainty about future income [

2], risk factors related to job and employment stability, and potential financial support from a life partner [

2]. In this context, the increasing number of one-person households is pointed out [

2]. As for housing prices, they have risen sharply in many countries in recent decades.

Figure 2 shows the percentage change in average apartment/house prices over 2010–2021 in various European countries. In Poland, prices have increased by 39.92% in this period (i.e., in these 11 years). However, as

Figure 2 shows, in many countries, prices have increased even more (in Estonia, Latvia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, for example). The above data are consistent with the data in the study by Sobieraj and Metelski [

39].

There is scientific evidence of episodes of price exuberance in many countries, e.g., the U.S. and the U.K. [

40], New Zealand [

41], and Australia (especially with respect to rental prices) [

42]. For years, residential real estate speculation and buying frenzy were fueled by excessive liquidity in the monetary system (lax monetary policy), which naturally led to some of this liquidity spilling over into residential real estate markets [

39,

43]. Part of the blame for this situation can be laid at the feet of the U.S. monetary authorities, whose imprudent policy of quantitative easing (in contrast to the Austrian school of economics) set a certain new standard in economics. The truth is that credit-driven economies are prone to the spread of housing booms [

43,

44]. The policies of national governments and central banks contribute to putting homeownership out of reach for young people for purely economic reasons. In turn, those who bought their home with a mortgage must expect that the cycle of interest rate increasing in various countries (which is currently the case) may lead to a decline in home prices, and many will face the problem of interest and principal repayments that they may not be able to afford. It should also be emphasized that government policies (after public consultations) should be prudent and judicious, as studies show that excessive governmental social assistance does not necessarily have a positive impact on homeownership rates [

20]. Still further studies point in particular to the need for well-structured [

45,

46] and developed mortgage markets [

7], which significantly accelerate the emancipation process of young adults, as they succeed more quickly in leaving their parental home and starting an independent adult life. There is scientific evidence of a strong correlation between mortgage credit availability and homeownership. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in the group of young adults who have the greatest problems with access to capital (which could be used for down payments) at a relatively early stage of their adult life and career development [

45].

To improve the outlook for the housing market as a whole in the mortgage finance system, flexibility in mortgage repayment is particularly important [

46]. Due to the increasing economic turbulence in the markets, some financial engineering mechanisms are desirable to appropriately mitigate the risk so that young people are not exposed to excessive risk [

46]. In this area, research has already been conducted that has shown that loans with adjustable interest rates (adjustable-rate mortgages) are the most appropriate form of financing.

Another important point is that it is becoming increasingly difficult for young people to actually identify their housing preferences [

7], regardless of the level of economic development of the country from which these young people come. The point is that this phenomenon cannot be explained by the economic situation, nor by the level of development, liquidity or stability of the housing markets themselves [

7]. Other studies have shown a relationship between financial strain and outstanding financial debt of young adults (mainly in the form of student loans) and the lack of desire for homeownership [

47]. In other words, financial strain is a factor that does not positively influence the desire for homeownership, but rather discourages potential buyers. The increasing credit and financial burden of societies has a negative impact on young adults, which has socioeconomic consequences and demonstrably worsens their chances of homeownership [

47].

Economists predict that the current processes will continue in the current decade, leading to a general decline in the relative level of home ownership [

10,

48]. More specifically, although there will be a net increase in the number of new homes and new households (i.e., the absolute number of homeowners will increase), overall renting will dominate as the absolute number of renters will increase by a larger proportion [

10]. In general, rising housing prices and the lack of an adequate financing system mean that more and more young people will be excluded from owning a home and will become part of a generation of renters [

49]. Therefore, it is likely that the housing market will be a renter’s market in the future [

10]. Additionally, it is the lack of access to home ownership and the strong need of young adults to create some kind of housing for themselves that leads to a rapidly growing rental sector [

16]. On the other hand, the proportion of young adults still living with their parents is also rapidly increasing [

31]. These are now two strongly dominant trends that are setting the direction in which housing markets are developing worldwide [

31]. It is also worth highlighting the increasing degree of financialization of housing markets themselves [

31], which in many cases even makes it impossible for young adults to become homeowners [

16,

50]. There is also a body of research that argues for the advantage of renting over owning [

17], especially when considering the average duration of homeownership. This perception of choice of housing form is justified, for example, for the US market, as pointed out by Beracha and Johnson [

17]. Regarding the choice of housing form, these authors adopted the position of indifference, assuming that it is reasonable to consider the appropriate relationship between the rent and the housing price, taking into account the indicators of volatility of housing prices [

17]. However, this type of evaluation should pay special attention to the specifics of the market in question, i.e., demographics, cultural factors, social habits, and so on. In other words, it is difficult to make a similar assessment for other markets, e.g., European or Polish, based on the experience of the American market, which is simply different [

10,

48]. It should also be emphasized that homeownership has a number of positive aspects from both macro- and micro perspectives [

51]. Regarding the latter aspect, homeownership leads to greater social participation and, at the same time, to more savings in households. As for the first aspect, ownership promotes consumption and investment and has a positive impact on public finances. Additionally, it is worth noting that homeownership rates are affected by appropriate government policies, especially tax distortions [

51,

52]. In the case of unfavorable tax laws, the cost of owner-occupied housing increases [

52]. Therefore, it is difficult to imagine a stable housing sector without government action to reduce marginal tax rates [

16,

52,

53]. Important issues for policymakers and decision makers to consider include taxes on tangible property (cadastral), taxes on the transfer of residential property, rent-related taxes, capital gains taxes, cost of owner-occupied housing, imputed income from rental housing [

53], and mortgage tax credits [

16]. One proposed solution that works well is the possibility of mortgage interest deductions [

53] or property tax deductions, as well as mechanisms that interact with capital gains from homeownership [

16].

It is important to emphasize that, in addition to typical factors, such as location and price, certain building characteristics (e.g., energy consumption or whether the building has been modernized in this regard) may also play a role in housing preferences [

54]. The energy efficiency of new buildings compared to older buildings can influence preferences when renting or buying a new home. Newer buildings designed with energy efficiency in mind may be more attractive to renters and buyers who value lower energy bills and carbon footprints [

55,

56]. It is important to keep this in mind. Indeed, research has shown that rental properties with higher energy scores are more likely to attract tenants [

57]. In addition, government stimulus programs often target building retrofits and efficient new construction [

56].

In summary, there are many aspects that influence young people’s adequate decisions about their preferred form of housing. In particular, individual decisions depend on the economic situation of a particular country, its background, and cultural values. Additionally important are appropriate programs and policies implemented at both central and local levels, i.e., different types of housing programs, adequate tax regimes, and the existence of a well-developed mortgage finance system with appropriate tools to mitigate financial risk.

4. Results

First, several important criteria for fitting the model were reviewed to further test the proposed hypotheses. These criteria take the form of global and local tests [

64,

93]. The strength of the local test alone is not important if the global tests are not met. Local tests assess the significance of individual paths in the model, while global tests assess the overall fit of the model [

94]. The latter are the starting point for validating the obtained results and evaluating the overall fit of the model. A model that is well fitted provides more credible results. If it passes these global tests, the

p-values for the hypothesized relationships are considered. On the other hand, if the

p-values support the relationships under investigation, but the model itself has a poor fit, these results cannot be taken seriously [

93].

Figure 8 shows the global and local test criteria that must be met to assess the reliability of the results.

The next step was to evaluate the r-squared values (i.e., the percentage of variance explained). These values must not be too low, because then the results are considered unreliable, since the variability of the explanatory variable does not explain an acceptable and satisfactory percentage of the variability of the endogenous variable [

95,

96]. In the case of the model developed for the purpose of this study, the r-squared value is 0.27, indicating moderately sufficient explanatory power [

97,

98]. It should be emphasized that the r-squared values in the mediation model (path model) are not generally accepted as a measure of effect size, and thus there is no specific threshold for what constitutes a low value [

95]. Therefore, the accepted r-squared values for a mediation model depend on the context and the specific research question [

98].

The last important point for evaluating the results and testing the proposed research hypotheses is the direction of the regression, indicated by the standardized and unstandardized estimates of the coefficients and, in particular, by their sign. For example, assuming that the number of dependents affects the propensity to purchase a home, and the actual results show that it has a negative effect (reducing the propensity to purchase a home), provides some sort of counterevidence. The detailed results are presented in

Table 8 and

Table 9.

Table 9, in turn, shows the relationships between the different variables specifically with respect to the hypotheses tested. It proves that hypotheses H3, H5, and H8 were positively verified. In the other cases, namely H1, H2, H4, H6, and H7, the hypotheses were disproved, with some contrary evidence found in two cases (H2 and H7).

First, it was found that there is a relationship between the variables EV and DV. Baron and Kenny [

72] argue that in order to test a mediation model, there should be a significant relationship between EV and DV. The development of a mediation model describing the relationship between variables X and Y, which requires the inclusion of some type of intermediate variable, assumes that the relationship between EV and DV is statistically significant. This is indeed the case for the EV and both DVs used in the model under study.

Among other things, the study shows that gender has a statistically significant relationship with rental preferences. That is, women show less interest in renting an apartment or a house and are more likely to own a home (although the latter relationship is not statistically significant). The same is true for the “age group” variable. The higher the age group, the lower the propensity to buy a house. This may be due to habit or convenience. In other words, those who have rented for long enough have become accustomed to it and do not want to change their preferences. This is supported by the evidence for hypothesis H5. Similarly, the size of the resident population in the hometown leads to a higher willingness to buy a house. This can be implicitly deduced from the study of Wessel and Lunke [

99]. Overall, the results show that some individuals who already live for rent consider buying an apartment or house, while others stick to the renting option, i.e., want to maintain the status quo. The beta coefficients for direct correlations are positive in both cases. This is precisely the reason that justifies that, in order to better understand the phenomenon under study, some kind of mediation model was needed to better explain these relationships by considering mediating variables.

Table 10 again shows the goodness-of-fit of the obtained mediation (path) model.

5. Discussion

Rapidly deteriorating housing conditions for young adults around the world pose a serious policy challenge. This paper draws on a survey of young Polish renters aged 18 to 45 to examine their preferences for homeownership over renting. The study investigates how young Polish renters perceive renting an apartment and, in this context, formulates eight research hypotheses, of which only three could be confirmed: H3, H5, and H8. In two cases (H2 and H7), counter-evidence to the hypotheses was provided. Therefore, the following conclusions can be drawn. Length of tenancy is an important mediating variable affecting young adults’ housing preferences. The longer a person rents an apartment, the less willing they are to change their status quo. The results of the mediation analysis are consistent with findings from Zillow’s [

100] report on consumer housing trends that the longer someone rents, the less desire there is for homeownership. More than half of renters who do not want to move have lived in rental housing for five or more years, the report found. Similar results were found in California, as reported by the California Department of Real Estate [

101]. Therefore, it is critical for housing policy to promote homeownership awareness and encourage young people to consider homeownership at a young age. In addition, individuals who pay a higher rent are more inclined to shift their preference to homeownership. They have a better understanding of existing housing alternatives that could offer them the opportunity to pay off their mortgage at rent-like rates. The study also showed that relationship status is not a significant mediating variable (as it could not be confirmed that the variable m7 mediates the positive effect of ev1 on dv1). However, counter-evidence was found. A relationship with a partner encourages young adults already renting to maintain their status quo (and stay with the rental option). One might have expected the marital or relationship status of young adults to be a factor encouraging them to strengthen their family ties, which, according to the conventional view, requires owning a home. Moreover, previous research has shown that children who grow up in households with home ownership tend to perform better at school [

17]. In addition, there is scientific evidence that homeownership is associated with better health outcomes than renting [

102] and that homeowners are more likely to be satisfied with their homes, have higher self-esteem, and suffer less from economic strain, depression, and problematic alcohol use than renters [

15]. Homeownership also allows families to build assets and serves as a measure of financial security [

48]. However, for the cohort of Polish renters studied, the results do not support the hypothesis that individuals who live with their partner in any form (whether marital or nonmarital) also have an increased need for homeownership. Understanding this requires a deeper analysis of the nature of modern relationships and a clear understanding of the erosion of the traditional family model as it has been understood in the past. Along these lines, Simpson and Overall [

103] have found that families have recently become less integrated on a global scale than in the past. This is evident from statistical data on marriage breakdown, cohabitation dissolution, and the rising number of one-person households. The authors argue that the growing insecurity associated with modern relationships can lead to a paradoxical sense of insecurity and instability among those living in such relationships. For example, individuals who declare that they are in a marriage or cohabiting relationship may not wish to risk the additional financial burdens that would result from the dissolution of such a relationship (because they are uncertain whether the relationship can be sustained in the long term). The termination of such a relationship would undoubtedly significantly complicate the borrowers’ legal situation and deprive them of their freedom and flexibility in life. In many cases, this would mean that people who have separated would have to continue to make joint loan repayments or live (with their ex-partner) in a shared apartment or house after their separation. In other words, young adults may be aware that the duration of loan repayments does not necessarily correspond to the duration of the relationship (whether marriage or cohabitation). A young couple unsure about the dissolution of their relationship may not want to buy shared housing units [

104]. Instead, they might opt for a living-apart-together relationship (LAT), which involves fewer public expressions of commitment such as a shared apartment or house [

105]. Renting is also an option, as it carries less risk of partnership dissolution than home ownership [

106].

The variables “raising children” and “dependents” also do not prove to be statistically significant mediators of tenants’ willingness to change their preferences towards home ownership. In the case of the variable “raising children”, the opposite is the case. Young adults raising children may be afraid of the additional financial burdens that might be associated with buying a house. Raising children is already a major financial challenge by nature, so the reluctance to face additional financial risk factors should not surprise anyone. After all, buying a house and then paying off the mortgage puts borrowers at risk. To tackle this problem, the government should launch appropriate housing programs specifically targeting these people, because family policy and the fight against negative demographic trends are part of every government’s policy. According to Sobieraj and Metelski [

39], programs to support young people in Poland were implemented earlier and should be adapted to the changed circumstances. Scientific research suggests that young adults raising children are fearful of the additional financial burdens associated with buying a home [

107,

108]. Low-income families in particular may be further burdened by expenses such as food, housing, and petrol [

108].

Last but not least, the present study proves a positive mediation effect of the variable “mortgage interest compared to rentals” on the association between “I/We rent an apartment or house” and “I/We want to buy an apartment or house”, and a negative mediation effect of the same mediation variable on the association between “I/We rent an apartment or house” and “renting preference”. The above mediation effect implies that an appropriate housing policy should include an information campaign that—firstly—makes young people aware that an alternative to renting is to finance one’s own apartment or house with a mortgage and that the amount of the mortgage payment itself need not necessarily be significantly higher than the amount of the payments associated with renting. Considering the evidence for hypothesis H8, it appears that mortgage loan plans could be structured more appropriately; for example, spread over a longer time horizon.