From Genome to Phenotype: An Integrative Approach to Evaluate the Biodiversity of Lactococcus lactis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Main Characteristics of the L. lactis Species

2.1. Taxonomic Features

2.2. Ecological Niches

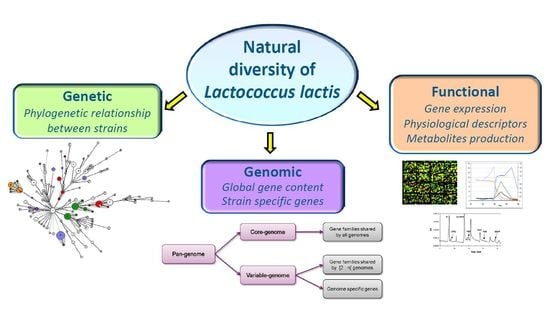

3. Lactococcus lactis: Multiple Levels of Diversity

3.1. Genetic Structure of L. lactis

3.2. Genomic Diversity

3.3. Functional Diversity

4. From Genome to Phenotype: Original Functions Explained Using an Integrated Approach

4.1. Range of Raffinose Metabolism

4.2. Different Types of Diacetyl/Acetoin Production

5. Technical and Specific Properties of Environmental Strains for New Applications

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meucci, A.; Zago, M.; Rossetti, L.; Fornasari, M.E.; Bonvini, B.; Tidona, F.; Povolo, M.; Contarini, G.; Carminati, D.; Giraffa, G. Lactococcus hircilactis sp. nov. and Lactococcus laudensis sp. nov., isolated from milk. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2091–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bali, V.; Panesar, P.S.; Bera, M.B.; Kennedy, J.F. Bacteriocins: Recent trends and potential applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinane, C.M.; Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P. Microbial solutions to microbial problems; lactococcal bacteriocins for the control of undesirable biota in food. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 98, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzoli, R.; Bosco, F.; Mizrahi, I.; Bayer, E.A.; Pessione, E. Towards lactic acid bacteria-based biorefineries. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1216–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleifer, K.H.; Kraus, J.; Dvorak, C.; Kilpper-Bälz, R.; Collins, M.D.; Fischer, W. Transfer of Streptococcus lactis and related streptococci to the genus Lactococcus gen. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1985, 6, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, T.; Balcázar, J.L.; Peix, A.; Valverde, A.; Velázquez, E.; de Blas, I.; Ruiz-Zarzuela, I. Lactococcus lactis subsp. tructae subsp. nov. isolated from the intestinal mucus of brown trout (Salmo trutta) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 1894–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, L.J.H.; Brown, J.C.S.; Davey, G.P. Two methods for the genetic differentiation of Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis and cremoris based on differences in the 16S rRNA gene sequence. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1998, 166, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, Z.Y.; Dobos, M.; Limsowtin, G.K.Y.; Powell, I. Integrated polymerase chain reaction-based procedures for the detection and identification of species and subspecies of the Gram-positive bacterial genus Lactococcus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 93, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godon, J.-J.; Delorme, C.; Ehrlich, S.D.; Renault, P. Divergence of genomic sequences between Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis and Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 4045–4047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Corroler, D.; Desmasures, N.; Gueguen, M. Correlation between polymerase chain reaction analysis of the histidine biosynthesis operon, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis and phenotypic characterization of dairy Lactococcus isolates. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 51, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beimfohr, C.; Ludwig, W.; Schleifer, K.-H. Rapid genotypic differentiation of Lactococcus lactis subspecies and biovar. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1997, 20, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Okamoto, T. Rapid PCR-based method which can determine both phenotype and genotype of Lactococcus lactis subspecies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 2209–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.W.; Leenhouts, K.; Burghoorn, J.; Brands, J.R.; Venema, G.; Kok, J. A chloride-inducible acid resistance mechanism in Lactococcus lactis and its regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 27, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, M.; Rossello-Mora, R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19126–19131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, D.; Casey, A.; Altermann, E.; Cotter, P.D.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; McAuliffe, O. Evaluation of Lactococcus lactis iolates from non-dairy sources with potential dairy applications reveals extensive phenotype-genotype disparity and implications for a revised species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3961–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, D.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; McAuliffe, O. From field to fermentation: The origins of Lactococcus lactis and its domestication to the dairy environment. Food Microbiol. 2015, 47, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegmann, U.; O’Connell-Motherway, M.; Zomer, A.; Buist, G.; Shearman, C.; Canchaya, C.; Ventura, M.; Goesmann, A.; Gasson, M.J.; Kuipers, O.P.; et al. Complete genome sequence of the prototype lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 3256–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passerini, D.; Coddeville, M.; Le Bourgeois, P.; Loubière, P.; Ritzenthaler, P.; Fontagné-Faucher, C.; Daveran-Mingot, M.-L.; Cocaign-Bousquet, M. The carbohydrate metabolism signature of Lactococcus lactis strain A12 reveals its sourdough ecosystem origin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5844–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, H.; Gabriel, V.; Fontagné-Faucher, C. Biodiversity of lactic acid bacteria in French wheat sourdough as determined by molecular characterization using species-specific PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 135, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, W.J.; Davey, G.P.; Ward, L.J. Characterization of lactococci isolated from minimally processed fresh fruit and vegetables. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1998, 45, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini, F.; Celano, G.; Lattanzi, A.; Tedone, L.; Mastro, G.D.; Gobbetti, M.; Angelis, M.D. Lactic acid bacteria in durum wheat flour are endophytic components of the plant during its entire life cycle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 6736–6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procopio, R.E.L.; Arajo, W.L.; Maccheroni, W., Jr.; Azevedo, J.L. Characterization of an endophytic bacterial community associated with Eucalyptus spp. Genet. Mol. Res. 2009, 8, 1408–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemayehu, D.; Hannon, J.A.; McAuliffe, O.; Ross, R.P. Characterization of plant-derived lactococci on the basis of their volatile compounds profile when grown in milk. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 172, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serna Cock, L.; Rodriguez de Stouvenel, A. Lactic acid production by a strain of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis isolated from sugar cane plants. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 9, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golomb, B.L.; Marco, M.L. Lactococcus lactis metabolism and gene expression during growth on plant tissues. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lacerda, J.R.M.; da Silva, T.F.; Vollú, R.E.; Marques, J.M.; Seldin, L. Generally recognized as safe (GRAS) Lactococcus lactis strains associated with Lippia sidoides Cham. are able to solubilize/mineralize phosphate. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Teng, K.-L.; Chen, M.-L.; Zheng, H.-J.; Zhu, Y.-Q.; Zhong, J. Complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis CV56, a probiotic strain isolated from the vagina of healthy women. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 2886–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plumed-Ferrer, C.; Gazzola, S.; Fontana, C.; Bassi, D.; Cocconcelli, P.-S.; von Wright, A. Genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris Mast36, a strain isolated from bovine mastitis. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e00449-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tormo, H.; Ali Haimoud Lekhal, D.; Roques, C. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from raw goat milk and effect of farming practices on the dominant species of lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 210, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RMT Fromages de Terroir Group. The Microbiology of Raw Milk. Towards a Better Understanding of the Microbial Ecosystems of Milk and the Factors that Affect Them; Bronwen Percival: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-0993419409. [Google Scholar]

- Mallet, A.; Guéguen, M.; Kauffmann, F.; Chesneau, C.; Sesboué, A.; Desmasures, N. Quantitative and qualitative microbial analysis of raw milk reveals substantial diversity influenced by herd management practices. Int. Dairy J. 2012, 27, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panoff, J.-M.; Desmasures, N.; Thammavongs, B.; Guéguen, M. In situ protection of microbiodiversity is under consideration. Microbiology 2002, 148, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, M.S.; Musafija-Jeknic, T.; Sandine, W.E.; Giovannoni, S.J. An ecological study of lactic acid bacteria: Isolation of new strains of Lactococcus including Lactococcus lactis subspecies cremoris. J. Dairy Sci. USA 1995, 78, 1004–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montel, M.-C.; Buchin, S.; Mallet, A.; Delbes-Paus, C.; Vuitton, D.A.; Desmasures, N.; Berthier, F. Traditional cheeses: Rich and diverse microbiota with associated benefits. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 177, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tormo, H.; Delacroix-Buchet, A.; Lopez, C.; Ali Haimoud Lekhal, D.; Roques, C. Farm management practices and diversity of the dominant bacterial species in raw goat’s milk. Int. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 6, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolotin, A.; Wincker, P.; Mauger, S.; Jaillon, O.; Malarme, K.; Weissenbach, J.; Ehrlich, S.D.; Sorokin, A. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 2001, 11, 731–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiden, M.C.J.; Bygraves, J.A.; Feil, E.; Morelli, G.; Russell, J.E.; Urwin, R.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zurth, K.; Caugant, D.A.; et al. Multilocus sequence typing: A portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 3140–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rademaker, J.L.W.; Herbet, H.; Starrenburg, M.J.C.; Naser, S.M.; Gevers, D.; Kelly, W.J.; Hugenholtz, J.; Swings, J.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Diversity analysis of dairy and non-dairy Lactococcus lactis isolates, using a novel multilocus sequence analysis scheme and (GTG)5-PCR fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 7128–7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, E.; Alegría, Á.; Delgado, S.; Martín, M.C.; Mayo, B. Comparative phenotypic and molecular genetic profiling of wild Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis strains of the L. lactis subsp. lactis and L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotypes, isolated from starter-free cheeses made of raw milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 5324–5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Sun, Z.; Liu, W.; Yu, J.; Song, Y.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, J.; Shao, Y.; Menghe, B.; Zhang, H. Multilocus sequence typing of Lactococcus lactis from naturally fermented milk foods in ethnic minority areas of China. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 2633–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passerini, D.; Beltramo, C.; Coddeville, M.; Quentin, Y.; Ritzenthaler, P.; Daveran-Mingot, M.-L.; Bourgeois, P.L. Genes but not genomes reveal bacterial domestication of Lactococcus lactis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeigler, D.R. Gene sequences useful for predicting relatedness of whole genomes in bacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukjancenko, O.; Wassenaar, T.M.; Ussery, D.W. Comparison of 61 sequenced Escherichia coli genomes. Microb. Ecol. 2010, 60, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergthorsson, U.; Ochman, H. Distribution of chromosome length variation in natural isolates of Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1998, 15, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, W.J.; Ward, L.J.H.; Leahy, S.C. Chromosomal diversity in Lactococcus lactis and the origin of dairy starter cultures. Genome Biol. Evol. 2010, 2, 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, S.; Zomer, A.; de Jager, V.; Bottacini, F.; van Hijum, S.A.F.T.; Mahony, J.; van Sinderen, D. Complete genome of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris UC509.9, host for a model lactococcal P335 bacteriophage. Genome Announc. 2013, 1, e00119-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, S.; McAuliffe, O.E.; Coffey, A.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Ross, R.P. Plasmids of lactococci-genetic accessories or genetic necessities? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 30, 243–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siezen, R.J.; Bayjanov, J.R.; Felis, G.E.; van der Sijde, M.R.; Starrenburg, M.; Molenaar, D.; Wels, M.; van Hijum, S.A.F.T.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Genome-scale diversity and niche adaptation analysis of Lactococcus lactis by comparative genome hybridization using multi-strain arrays. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallico, V.; Ross, R.P.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; McAuliffe, O. Novel conjugative plasmids from the natural isolate Lactococcus lactis subspecies cremoris DPC3758: a repository of genes for the potential improvement of dairy starters. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 3593–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siezen, R.J.; Renckens, B.; van Swam, I.; Peters, S.; van Kranenburg, R.; Kleerebezem, M.; de Vos, W.M. Complete sequences of four plasmids of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris SK11 reveal extensive adaptation to the dairy environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 8371–8382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, S.; Stockdale, S.; Bottacini, F.; Mahony, J.; van Sinderen, D. The Lactococcus lactis plasmidome: Much learnt, yet still lots to discover. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 1066–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górecki, R.K.; Koryszewska-Bagińska, A.; Gołębiewski, M.; Żylińska, J.; Grynberg, M.; Bardowski, J.K. Adaptative potential of the Lactococcus lactis IL594 strain encoded in its 7 plasmids. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sesma, F.; Gardiol, D.; de Ruiz Holgado, A.P.; de Mendoza, D. Cloning of the citrate permease gene of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar Diacetylactis and expression in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990, 56, 2099–2103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tanous, C.; Chambellon, E.; Yvon, M. Sequence analysis of the mobilizable lactococcal plasmid pGdh442 encoding glutamate dehydrogenase activity. Microbiology 2007, 153, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallico, V.; McAuliffe, O.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Ross, R.P. Plasmids of raw milk cheese isolate Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar Diacetylactis DPC3901 suggest a plant-based origin for the strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 6451–6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarazanova, M.; Beerthuyzen, M.; Siezen, R.; Fernandez-Gutierrez, M.M.; de Jong, A.; van der Meulen, S.; Kok, J.; Bachmann, H. Plasmid complement of Lactococcus lactis NCDO712 reveals a novel pilus gene cluster. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyrand, M.; Guillot, A.; Goin, M.; Furlan, S.; Armalyte, J.; Kulakauskas, S.; Cortes-Perez, N.G.; Thomas, G.; Chat, S.; Péchoux, C.; et al. Surface proteome analysis of a natural isolate of Lactococcus lactis reveals the presence of pili able to bind human intestinal epithelial cells. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2013, 12, 3935–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, D.T.L.; Tran, T.-L.; Duviau, M.-P.; Meyrand, M.; Guérardel, Y.; Castelain, M.; Loubière, P.; Chapot-Chartier, M.-P.; Dague, E.; Mercier-Bonin, M. Unraveling the role of surface mucus-binding protein and pili in muco-adhesion of Lactococcus lactis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegmann, U.; Overweg, K.; Jeanson, S.; Gasson, M.; Shearman, C. Molecular characterization and structural instability of the industrially important composite metabolic plasmid pLP712. Microbiology 2012, 158, 2936–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, A.R.; Setyawati, M.C.; Bayjanov, J.R.; Alkema, W.; van Hijum, S.A.F.T.; Bron, P.A.; Hugenholtz, J. Diversity in robustness of Lactococcus lactis strains during heat stress, oxidative stress, and spray drying stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guellerin, M.; Passerini, D.; Fontagné-Faucher, C.; Robert, H.; Gabriel, V.; Loux, V.; Klopp, C.; Loir, Y.L.; Coddeville, M.; Daveran-Mingot, M.-L.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis A12, a strain isolated from wheat sourdough. Genome Announc. 2016, 4, e00692-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siezen, R.J.; Bayjanov, J.; Renckens, B.; Wels, M.; van Hijum, S.A.F.T.; Molenaar, D.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis KF147, a plant-associated lactic acid bacterium. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 2649–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmann, H.; Starrenburg, M.J.C.; Dijkstra, A.; Molenaar, D.; Kleerebezem, M.; Rademaker, J.L.W.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Regulatory phenotyping reveals important diversity within the species Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 5687–5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaisne, A.; Guellerin, M.; Laroute, V.; Laguerre, S.; Cocaign-Bousquet, M.; Le Bourgeois, P.; Loubiere, P. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of dairy Lactococcus lactis biodiversity in milk: Volatile organic compounds as discriminating markers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 4643–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siezen, R.J.; Starrenburg, M.J.C.; Boekhorst, J.; Renckens, B.; Molenaar, D.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Genome-scale genotype-phenotype matching of two Lactococcus lactis Isolates from plants identifies mechanisms of adaptation to the plant niche. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, I.; Vadeboncoeur, C.; Moineau, S. Characterization of genes involved in the metabolism of α-galactosides by Lactococcus raffinolactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 4049–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machielsen, R.; Siezen, R.J.; van Hijum, S.A.F.T.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Molecular description and industrial potential of Tn6098 conjugative transfer conferring alpha-galactoside metabolism in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aymes, F.; Monnet, C.; Corrieu, G. Effect of alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase inactivation on alpha-acetolactate and diacetyl production by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar Diacetylactis. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 1999, 87, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Quintáns, N.; Repizo, G.; Martín, M.; Magni, C.; López, P. Activation of the diacetyl/acetoin pathway in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis bv. Diacetylactis CRL264 by acidic growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1988–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drider, D.; Bekal, S.; Prévost, H. Genetic organization and expression of citrate permease in lactic acid bacteria. Genet. Mol. Res. 2004, 3, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kempler, G.M.; McKay, L.L. Improved medium for detection of citrate-fermenting Streptococcus lactis subsp. diacetylactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1980, 39, 926–927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Passerini, D.; Laroute, V.; Coddeville, M.; Le Bourgeois, P.; Loubière, P.; Ritzenthaler, P.; Cocaign-Bousquet, M.; Daveran-Mingot, M.-L. New insights into Lactococcus lactis diacetyl- and acetoin-producing strains isolated from diverse origins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 160, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayad, E.H.E.; Verheul, A.; Wouters, J.T.M.; Smit, G. Antimicrobial-producing wild lactococci isolated from artisanal and non-dairy origins. Int. Dairy J. 2002, 12, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Derrien, M.; Levenez, F.; Brazeilles, R.; Ballal, S.A.; Kim, J.; Degivry, M.-C.; Quéré, G.; Garault, P.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T.; et al. Ecological robustness of the gut microbiota in response to ingestion of transient food-borne microbes. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2235–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabich, A.J.; Jones, S.A.; Chowdhury, F.Z.; Cernosek, A.; Anderson, A.; Smalley, D.; McHargue, J.W.; Hightower, G.A.; Smith, J.T.; Autieri, S.M.; et al. Comparison of carbon nutrition for pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli strains in the mouse intestine. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, K.; Meyrand, M.; Corthier, G.; Monnet, V.; Mistou, M.-Y. Proteomic investigation of the adaptation of Lactococcus lactis to the mouse digestive tract. Proteomics 2008, 8, 1661–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, K.; Shirai, T.; Ochiai, H.; Kasao, M.; Hayakawa, K.; Kimura, M.; Sansawa, H. Blood-pressure-lowering effect of a novel fermented milk containing γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in mild hypertensives. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, K.; Kimura, M.; Kasaha, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Sansawa, H.; Yamori, Y. Effect of a γ-aminobutyric acid-enriched dairy product on the blood pressure of spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive Wistar–Kyoto rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, H.; Takishima, T.; Kometani, T.; Yokogoshi, H. Psychological stress-reducing effect of chocolate enriched with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in humans: Assessment of stress using heart rate variability and salivary chromogranin A. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Yokozawa, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Sasaki, S. Protective effect of γ-aminobutyric acid against glycerol-induced acute renal failure in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004, 42, 2009–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain | Subspecies | Date | Genome Size (Mb) | Chrom. Size (Mb) | Number of Plasmids | Protein | Isolation Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL1403 | lactis | 2001 | 2.36559 | 2.36559 | 0 | 2277 | Cheese starter culture |

| KF147 | lactis | 2009 | 2.63565 | 2.59814 | 1 | 2445 | Mung bean sprouts |

| CNCM I-1631 | lactis | 2011 | 2.51133 | N.D. | 2403 | Fermented milk | |

| CV56 | lactis | 2011 | 2.51874 | 2.39946 | 5 | 2378 | Vaginal flora |

| IO-1 | lactis | 2012 | 2.42147 | 2.42147 | 0 | 2229 | Water in kitchen sink drain pit |

| Dephy 1 | lactis | 2013 | 2.60355 | N.D. | 2459 | N.D. | |

| KLDS 4.0325 | lactis | 2013 | 2.59549 | 2.58925 | 3 | 2448 | Homemade koumiss |

| LD61 | lactis bv. diacetylactis | 2013 | 2.59924 | N.D. | 2490 | Starter culture for dairy fermentation | |

| TIFN2 | lactis bv. diacetylactis | 2013 | 2.50507 | N.D. | 2296 | Cheese starter | |

| TIFN4 | lactis bv. diacetylactis | 2013 | 2.55039 | N.D. | 2349 | Cheese starter | |

| YF11 | lactis | 2013 | 2.52731 | N.D. | 2328 | Dairy | |

| 511 | lactis | 2014 | 2.48081 | N.D. | 2304 | N.D. | |

| 1AA59 | lactis | 2014 | 2.57654 | N.D. | 2406 | Artisanal cheese | |

| AI06 | lactis | 2014 | 2.39809 | 2.39809 | 0 | 2178 | Acai pulp |

| Bpl1 | lactis | 2014 | 2.3057 | N.D. | 2092 | Wild flies | |

| CECT 4433 | lactis | 2014 | 2.57915 | N.D. | 2290 | Cheese | |

| GL2 | lactis bv. diacetylactis | 2014 | 2.33892 | N.D. | 2135 | Dromedary milk | |

| NCDO 2118 | lactis | 2014 | 2.59226 | 2.5546 | 1 | 2382 | Frozen peas |

| S0 | lactis | 2014 | 2.4887 | 2.4887 | 0 | 2311 | Fresh raw milk |

| ATCC 19435 | lactis | 2015 | 2.54729 | N.D. | 2373 | Dairy starter | |

| CRL264 | lactis bv. diacetylactis | 2015 | 2.57372 | N.D. | 2446 | Cheese | |

| DPC6853 | lactis | 2015 | 2.50715 | N.D. | 2116 | Corn | |

| E34 | lactis | 2015 | 2.37566 | N.D. | 2217 | Silage | |

| K231 | lactis | 2015 | 2.33604 | N.D. | 2178 | White kimchii | |

| K337 | lactis | 2015 | 2.44552 | N.D. | 2263 | White kimchii | |

| KF134 | lactis | 2015 | 2.4634 | N.D. | 2282 | Alfalfa and radish sprouts | |

| KF146 | lactis | 2015 | 2.57452 | N.D. | 2408 | Alfalfa and radish sprouts | |

| KF196 | lactis | 2015 | 2.44589 | N.D. | 2282 | Japanese kaiwere shoots | |

| KF201 | lactis | 2015 | 2.37639 | N.D. | 2222 | Sliced mixed vegetables | |

| KF24 | lactis | 2015 | 2.61922 | N.D. | 2483 | Alfalfa sprouts | |

| KF282 | lactis | 2015 | 2.65125 | N.D. | 2471 | Mustard and cress | |

| KF67 | lactis | 2015 | 2.6843 | N.D. | 2514 | Grapefruit juice | |

| KF7 | lactis | 2015 | 2.36676 | N.D. | 2209 | Alfalfa sprouts | |

| Li-1 | lactis | 2015 | 2.47593 | N.D. | 2303 | Grass | |

| LMG 7760 | lactis | 2015 | 2.24545 | N.D. | 2072 | N.D. | |

| LMG 14418 | lactis | 2015 | 2.41093 | N.D. | 2275 | Bovine milk | |

| LMG 8520 | lactis | 2015 | 2.43558 | N.D. | 2060 | Leaf hopper | |

| LMG 8526 | lactis | 2015 | 2.47749 | N.D. | 2304 | Chinese radish seeds | |

| LMG 9446 | lactis | 2015 | 2.4884 | N.D. | 2324 | Frozen peas | |

| LMG 9447 | lactis | 2015 | 2.70754 | N.D. | 2552 | Frozen peas | |

| M20 | lactis | 2015 | 2.67432 | N.D. | 2535 | Soil | |

| ML8 | lactis | 2015 | 2.52187 | N.D. | 2373 | Dairy starter | |

| N42 | lactis | 2015 | 2.74392 | N.D. | 2540 | Soil and grass | |

| NCDO895 | lactis | 2015 | 2.47306 | N.D. | 2319 | Dairy starter | |

| UC317 | lactis | 2015 | 2.49842 | N.D. | 2357 | Dairy starter | |

| A12 | lactis | 2016 | 2.73062 | 2.6039 | 4 | 2487 | Sourdough |

| DRA4 | lactis bv. diacetylactis | 2016 | 2.45755 | N.D. | 2283 | Dairy starter | |

| JCM 7638 | lactis | 2016 | 2.39386 | N.D. | - | N.D | |

| Ll1596 | lactis | 2016 | 2.39296 | N.D. | 2237 | Teat canal | |

| NBRC 100933 | lactis | 2016 | 2.54762 | N.D. | 2406 | N.D | |

| RTB018 | lactis | 2016 | 2.48665 | N.D. | 2168 | Intestinal content of rainbow trout | |

| NBRC 100931 | hordniae | 2016 | 2.42828 | N.D. | 2079 | Leaf hopper | |

| SK11 | cremoris | 2006 | 2.59835 | 2.43859 | 5 | 2412 | Dairy |

| MG1363 | cremoris | 2007 | 2.52948 | 2.52948 | 0 | 2400 | Dairy |

| NZ9000 | cremoris | 2010 | 2.53029 | 2.53029 | 0 | 2404 | Dairy |

| A76 | cremoris | 2011 | 2.5771 | 2.45262 | 4 | 2382 | Cheese production |

| UC509.9 | cremoris | 2012 | 2.45735 | 2.25043 | 8 | 2188 | Irish Dairy |

| KW2 | cremoris | 2013 | 2.42705 | 2.42705 | 0 | 2223 | Fermented corn |

| TIFN1 | cremoris | 2013 | 2.67978 | N.D. | 2285 | Cheese starter | |

| TIFN3 | cremoris | 2013 | 2.72521 | N.D. | 2291 | Cheese starter | |

| TIFN5 | cremoris | 2013 | 2.54151 | N.D. | 2232 | Cheese starter | |

| TIFN6 | cremoris | 2013 | 2.59151 | N.D. | 2334 | Cheese starter | |

| TIFN7 | cremoris | 2013 | 2.63409 | N.D. | 2505 | Cheese starter | |

| A17 | cremoris | 2014 | 2.67994 | N.D. | 2367 | Taiwan fermented cabbage | |

| GE214 | cremoris | 2014 | 2.80103 | N.D. | 2603 | Cheese | |

| HP(T) | cremoris | 2014 | 2.26951 | N.D. | 2042 | Mixed strain dairy starter culture | |

| DPC6856 | cremoris | 2015 | 2.86238 | N.D. | 2606 | Bovine rumen | |

| DPC6860 | cremoris | 2015 | 2.60744 | N.D. | 2261 | Grass | |

| Mast36 | cremoris | 2015 | 2.60534 | N.D. | 2414 | Milk from a cow with mastitis | |

| AM2 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.48157 | N.D. | 2254 | Dairy starter | |

| B40 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.49846 | N.D. | 2220 | Dairy starter | |

| FG2 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.58614 | N.D. | 2260 | Dairy starter | |

| HP | cremoris | 2016 | 2.39396 | N.D. | 2132 | Dairy starter | |

| IBB477 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.85035 | 2.64217 | 5 | 2653 | Raw milk |

| KW10 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.36102 | N.D. | 2177 | Kaanga Wai | |

| LMG 6897 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.3672 | N.D. | 2101 | Cheese starter | |

| N41 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.61571 | N.D. | 2410 | Soil and grass | |

| NBRC 100676 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.34409 | N.D. | 2093 | N.D. | |

| NCDO763 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.48569 | N.D. | 2331 | Dairy starter | |

| P7266 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.00015 | N.D. | 1984 | Litter on pastures | |

| SK110 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.46761 | N.D. | 2241 | Dairy starter | |

| V4 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.54895 | N.D. | 2344 | Raw sheep milk | |

| WG2 | cremoris | 2016 | 2.54251 | N.D. | 2306 | Cheese |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laroute, V.; Tormo, H.; Couderc, C.; Mercier-Bonin, M.; Le Bourgeois, P.; Cocaign-Bousquet, M.; Daveran-Mingot, M.-L. From Genome to Phenotype: An Integrative Approach to Evaluate the Biodiversity of Lactococcus lactis. Microorganisms 2017, 5, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms5020027

Laroute V, Tormo H, Couderc C, Mercier-Bonin M, Le Bourgeois P, Cocaign-Bousquet M, Daveran-Mingot M-L. From Genome to Phenotype: An Integrative Approach to Evaluate the Biodiversity of Lactococcus lactis. Microorganisms. 2017; 5(2):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms5020027

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaroute, Valérie, Hélène Tormo, Christel Couderc, Muriel Mercier-Bonin, Pascal Le Bourgeois, Muriel Cocaign-Bousquet, and Marie-Line Daveran-Mingot. 2017. "From Genome to Phenotype: An Integrative Approach to Evaluate the Biodiversity of Lactococcus lactis" Microorganisms 5, no. 2: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms5020027

APA StyleLaroute, V., Tormo, H., Couderc, C., Mercier-Bonin, M., Le Bourgeois, P., Cocaign-Bousquet, M., & Daveran-Mingot, M. -L. (2017). From Genome to Phenotype: An Integrative Approach to Evaluate the Biodiversity of Lactococcus lactis. Microorganisms, 5(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms5020027