Methylglyoxal (MGO) in Italian Honey

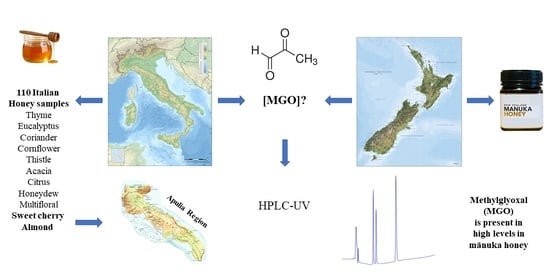

Abstract

:Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Chemicals

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization of Honey Samples

2.4. Analytical RP-HPLC

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Honey Samples

3.2. MGO Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biluca, F.C.; Braghini, F.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Costa, A.C.O.; Fett, R. Physicochemical profiles, minerals and bioactive compounds of stingless bee honey (Meliponinae). J. Food Compost. Anal. 2016, 50, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornara, L.; Biagi, M.; Xiao, J.; Burlando, B. Therapeutic properties of bioactive Compounds from different honeybee products. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Ruiz-Navajas, Y.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A. Functional properties of honey, propolis, and royal jelly. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Tulipani, S.; Romandini, S.; Bertoli, F.; Battino, M. Contribution of honey in nutrition and human health: A review. Med. J. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 3, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israili, Z.H. Antimicrobial properties of honey. Am. J. Ther. 2014, 21, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, A. The therapeutic effects of honey. Plymouth Stud. Sci. 2013, 6, 376–385. [Google Scholar]

- Manyi-Loh, C.E.; Clarke, A.M.; Ndip, R.N. An overview of honey: Therapeutic properties and contribution in nutrition and human health. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2011, 5, 844–852. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Honey as a source of dietary antioxidants: Structures, bioavailability and evidence of protective effects against human chronic diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burlando, B.; Cornara, L. Honey in dermatology and skin care: A review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2013, 12, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.K.; Hoekstra, M.J.; Hage, J.J.; Karim, R.B. Honey-medicated dressing: Transformation of an ancient remedy into modern therapy. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2013, 50, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbach, M.A.; Walsh, C.T. Antibiotics for Emerging Pathogens. Science 2009, 325, 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molan, P.C. The evidence and the rationale for the use of honey as a wound dressing. Wound Pract. Res. 2011, 19, 204–220. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, C. Antibiotics: Actions, Origins, Resistance; American Society for Microbiology (ASM) Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Gasparrini, M.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Mazzoni, L.; Giampieri, F. The Composition and Biological Activity of Honey: A Focus on Mānuka Honey. Foods 2014, 3, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anand, S.; Pang, E.; Livanos, G.; Mantri, N. Characterization of Physico-Chemical Properties and Antioxidant Capacities of Bioactive Honey Produced from Australian Grown Agastache rugosa and its Correlation with Colour and Poly-Phenol Content. Molecules 2018, 23, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buratti, S.; Benedetti, S.; Cosio, M.S. Evaluation of the antioxidant power of honey, propolis and royal jelly by amperometric flow injection analysis. Talanta 2007, 71, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreirra, I.C.F.R.; Aires, E.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Estevinho, L.M. Antioxidant activity of Portuguese honey samples: Different contributions of entire honey and phenolic extract. Food Chem. 2008, 114, 1438–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheldof, N.; Wang, X.H.; Engeseth, N.J. Identification and quantification of antioxidant components of honeys from various floral sources. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5870–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petretto, G.L.; Cossu, M.; Alamanni, M.C. Phenolic content, antioxidant and physico-chemical properties of Sardinian monofloral honeys. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raso, G.M.; Meli, R.; Di Carlo, G.; Pacilio, M.; Di Carlo, R. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 expression by flavonoids in macrophage J774A.1. Life Sci. 2001, 68, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Longo, R.; Russo, A.; Borrelli, F.; Sautebin, L. The role of the phenethyl ester of caffeic acid (CAPE) in the inhibition of rat lung cyclooxygenase activity by propolis. Fitoterapia 2002, 73, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albaridi, N.A. Antibacterial potency of honey. Int. J. Microbiol. 2019, 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saranraj, P.; Sivasakthi, S. Comprehensive review on honey: Biochemical and medicinal properties. J. Acad. Ind. Res. 2018, 6, 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bucekova, M.; Sojka, M.; Valachova, I.; Martinotti, S.; Ranzato, E.; Szep, Z.; Majtan, J. Bee-derived antibacterial peptide, defensin-1, promotes wound reepithelialisation in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bucekova, M.; Jardekova, L.; Juricova, V.; Bugarova, V.; Di Marco, G.; Gismondi, A.; Leonardi, D.; Farkasovska, J.; Godocikova, J.; Laho, M.; et al. Antibacterial activity of different blossom honeys: New findings. Molecules 2019, 24, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nolan, V.C.; Harrison, J.; Cox, J.A.G. Dissecting the antimicrobial composition of honey. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Price, C.L.; Knight, S.C. Methylglyoxal: Possible link between hyperglycaemia and immune suppression? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 20, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jiao, T.; Chen, Y.; Gao, N.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, M. Methylglyoxal induces systemic symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rückriemen, J.; Hohmann, C.; Hellwig, M.; Henle, T. Unique fluorescence and high-molecular weight characteristics of protein isolates from mānuka honey (Leptospermum scoparium). Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulman, S.E.L.; Tronci, G.; Goswami, P.; Carr, C.; Russell, S.J. Antibacterial properties of nonwoven wound dressings coated with mānuka honey or methylglyoxal. Materials (Basel) 2017, 10, 954. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.; Jenkins, L.; Rowland, R. Inhibition of biofilms through the use of mānuka honey. Wounds UK 2011, 7, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jervis-Bardy, J.; Foreman, A.; Bray, S.; Tan, L.; Wormald, P.J. Methylglyoxal-infused honey mimics the anti-Staphylococcus aureus biofilm activity of mānuka honey: Potential implication in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 1104–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwakman, P.H.S.; te Velde, A.A.; de Boer, L.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.J.E.; Zaat, S.A.J. Two major medicinal honeys have different mechanisms of bactericidal activity. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, 17709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Clearwater, M.J.; Revell, M.; Noe, S.; Manley-Harris, M. Influence of genotype, floral stage, and water stress on floral nectar yield and composition of mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium). Ann. Bot. 2018, 121, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weigel, K.U.; Opitz, T.; Henle, T. Studies on the occurrence and formation of 1,2-dicarbonyls in honey. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2004, 218, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.J.; Manley-Harris, M.; Molan, P.C. The origin of methylglyoxal in New Zealand mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium) honey. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 1050–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavric, E.; Wittmann, S.; Barth, G.; Henle, T. Identification and quantification of methylglyoxal as the dominant antibacterial constituent of Mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium) honeys from New Zealand. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; King, J.; Revell, M.; Manley-Harris, M.; Balks, M.; Janusch, F.; Dawson, M. Regional, annual, and individual variations in the dihydroxyacetone content of the nectar of maānuka (Leptospermum scoparium) in New Zealand. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 10332–10340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council EU. Council Directive 2001/110 Relating to Honey. Off. J. Eur. Communities L 2002, 10, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Method of Analysis, 19th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Honey Commission. Harmonized Methods of the International (European) Honey Commission. 2009, pp. 1–63. Available online: https://www.ihc-platform.net/ihcmethods2009.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Escriche, I.; Visquert, M.; Juan-Borras, M.; Fito, P. Influence of simulated industrial thermal treatments on volatile fractions of different varieties of honey. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirife, J.; Zamora, M.C.; Motto, A. The correlation between water activity and % moisture in honey: Fundamental aspects and application to Argentine honeys. J. Food Eng. 2006, 72, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wedmore, E. The accurate determination of the water content of honeys. Bee World 1955, 36, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, S.; Ruoff, K.; Persano Oddo, L. Physico-chemical methods for the characterisation of unifloral honeys: A review. Apidologie 2004, 35, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oddo, L.P.; Piazza, M.G.; Pulcini, P. Invertase activity in honey. Apidologie 1999, 30, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arena, E.; Ballistreri, G.; Tomaselli, F.; Fallico, B. Survey of 1,2-dicarbonyl compounds in commercial honey of different floral origin. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrott, J.; Haberlau, S.; Henle, T. Studies on the formation of methylglyoxal from dihydroxyacetone in Mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium) honey. Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 361, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, A.; Virjamo, V.; Tammela, P.; Fauch, L.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R. Screening bioactivity and bioactive constituents of Nordic unifloral honeys. Food Chem. 2017, 237, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, S.; Sulaiman, S.A.; Baig, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.; Liaqat, S.; Fatima, S.; Jabeen, S.; Shamim, N.; Othman, N.H. Honey as a potential natural antioxidant medicine: An insight into its molecular mechanisms of action. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 8367846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grainger, M.N.C.; Manley-Harris, M.; Lane, J.L.; Field, R.J. Kinetics of conversion of dihydroxyacetone to methylglyoxal in New Zealand mānuka honey: Part I---Honey systems. Food Chem. 2016, 202, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irish, J.; Blair, S.; Carter, D.A. The Antibacterial Activity of Honey Derived from Australian Flora. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilty, S.J.; Duval, M.; Chan, F.T.; Ferris, W.; Slinger, R. Methylglyoxal: (active agent of mānuka honey) in vitro activity against bacterial biofilms. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011, 1, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamarya, M.; Al-Meerib, A.; Al-Habori, M. Antioxidant activities and total phenolics of different types of honey. Nutr. Res. 2002, 22, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, S.; Pappalardo, M.; Brooks, P.; Williams, S.; Manley-Harris, M. A convenient new analysis of dihydroxyacetone and methylglyoxal applied to Australian Leptospermum honeys. J. Pharmacogn. Phytother. 2012, 4, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majtan, J. Methylglyoxal— A potential risk factor of mānuka honey in healing of diabetic ulcers. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 295494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Floral Origin | Geographical Origin | Number of Samples |

|---|---|---|

| Sweet Cherry | Apulia | 10 |

| Thyme | Apulia | 5 |

| Sardinia | 3 | |

| Sicily | 2 | |

| Almond | Apulia | 6 |

| Sicily | 4 | |

| Eucalyptus | Apulia | 3 |

| Calabria | 2 | |

| Lazio | 2 | |

| Sardinia | 1 | |

| Sicily | 1 | |

| Tuscany | 1 | |

| Coriander | Abruzzo | 2 |

| Apulia | 4 | |

| Emilia Romagna | 2 | |

| Marche | 2 | |

| Cornflower | Apulia | 4 |

| Lazio | 2 | |

| Marche | 2 | |

| Tuscany | 2 | |

| Thistle | Apulia | 2 |

| Calabria | 4 | |

| Sicily | 4 | |

| Acacia | Sardinia | 2 |

| Abruzzo | 1 | |

| Apulia | 2 | |

| Campania | 1 | |

| Piedmont | 1 | |

| Tuscany | 2 | |

| Veneto | 1 | |

| Citrus | Apulia | 4 |

| Basilicata | 2 | |

| Calabria | 2 | |

| Sicily | 2 | |

| Honeydew | Abruzzo | 1 |

| Aosta Valley | 2 | |

| Apulia | 2 | |

| Emilia Romagna | 1 | |

| Tuscany | 2 | |

| Trentino Alto Adige | 2 | |

| Multifloral | Apulia | 4 |

| Campania | 2 | |

| Calabria | 2 | |

| Emilia Romagna | 2 |

| Physicochemical Parameters | Sweet Cherry | Thyme | Almond | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | |

| HMF (mg/kg) | 21.59 ± 2.10 | 19.01 | 24.39 | 8.64 ± 1.74 | 5.86 | 10.97 | 12.41 ± 1.61 | 10.09 | 14.29 |

| aw | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.7 | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 0.51 | 0.71 | 0.55 ± 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.62 |

| Electrical conductivity (ms/cm) | 0.54 ± 0.09 | 0.4 | 0.64 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.5 ± 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.65 |

| Moisture content (%) | 16.47 ± 0.32 | 16 | 16.92 | 16.18 ± 0.87 | 15.13 | 17.11 | 14.87 ± 0.52 | 14.3 | 15.7 |

| pH | 4.05 ± 0.07 | 3.88 | 4.09 | 4.11 ± 0.17 | 3.87 | 4.32 | 4.58 ± 0.16 | 4.32 | 4.77 |

| Diastatic index values (Schade number) | 20.86 ± 5.94 | 11.4 | 31.2 | 30.33 ± 4.66 | 25.6 | 38.33 | 23.2 ± 5.49 | 15.2 | 30.4 |

| Physicochemical Parameters | Eucalyptus | Coriander | Cornflower | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | |

| HMF (mg/kg) | 28.94 ± 6.83 | 16.02 | 39.14 | 4.14 ± 1.3 | 2.31 | 5.72 | 21.52 ± 1.15 | 20.18 | 24.18 |

| aw | 0.6 ± 0.05 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.64 |

| Electrical conductivity (ms/cm) | 0.74 ± 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.3 | 0.37 | 0.5 ± 0.05 | 0.43 | 0.59 |

| Moisture content (%) | 16.29 ± 0.41 | 15.79 | 17.01 | 17.31 ± 0.4 | 16.6 | 17.8 | 17.88 ± 0.43 | 17.4 | 18.5 |

| pH | 4.05 ± 0.16 | 3.88 | 4.43 | 4.69 ± 0.02 | 4.66 | 4.72 | 4.44 ± 0.14 | 4.27 | 4.68 |

| Diastatic index values (Schade number) | 25.65 ± 4.07 | 17.8 | 31.4 | 17.3 ± 3.6 | 10.4 | 22.6 | 19.05 ± 4.95 | 11.2 | 26.4 |

| Physicochemical Parameters | Thistle | Acacia | Citrus | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | |

| HMF (mg/kg) | 14.29 ± 1.9 | 10.74 | 16.11 | 7.04 ± 2.11 | 5.09 | 11.28 | 11.67 ± 1.64 | 8.65 | 14.56 |

| aw | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.55 | 0.7 |

| Electrical conductivity (ms/cm) | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.22 ± 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.24 ± 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.34 |

| Moisture content (%) | 18.38 ± 0.84 | 17.13 | 19.44 | 18.24 ± 0.47 | 17.28 | 18.7 | 17.73 ± 1.25 | 14.9 | 20.56 |

| pH | 3.99 ± 0.05 | 3.88 | 4.03 | 3.92 ± 0.26 | 3.44 | 4.19 | 4.11 ± 0.15 | 3.94 | 4.35 |

| Diastatic index values (Schade number) | 19.37 ± 5.2 | 12.9 | 28.6 | 8.62 ± 2.48 | 5.3 | 12.2 | 9.8 ± 3.44 | 4.5 | 14.2 |

| Physicochemical Parameters | Honeydew | Multifloral | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | ||||

| HMF (mg/kg) | 5.72 ± 1.35 | 3.17 | 6.69 | 24.38 ± 1.70 | 20.97 | 26.01 | |||

| aw | 0.52 ± 0.08 | 0.32 | 0.61 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.56 | |||

| Electrical conductivity (ms/cm) | 1.07 ± 0.17 | 0.83 | 1.31 | 0.6 ± 0.14 | 0.32 | 0.75 | |||

| Moisture content (%) | 18.03 ± 0.31 | 17.54 | 18.61 | 16.83 ± 0.58 | 16.21 | 17.66 | |||

| pH | 4.61 ± 0.64 | 3.76 | 5.3 | 3.94 ± 0.1 | 3.77 | 4.04 | |||

| Diastatic index values (Schade number) | 22.94 ± 6.68 | 14.3 | 33.2 | 22.83 ± 4.24 | 14.9 | 27.6 | |||

| Honey Samples | Floral Origin | Geographical Origin | MGO (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sweet Cherry | Apulia | 23 |

| 2 | 18.2 | ||

| 3 | 17.9 | ||

| 4 | 17.9 | ||

| 5 | 17.8 | ||

| 6 | 10.3 | ||

| 7 | 22.9 | ||

| 8 | 21 | ||

| 9 | 20.6 | ||

| 10 | 16.6 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 18.62 ± 3.69 | ||

| 11 | Thyme | Apulia | 17 |

| 12 | 7.21 | ||

| 13 | 9.4 | ||

| 14 | 8.6 | ||

| 15 | 6.8 | ||

| 16 | Sardinia | 7.4 | |

| 17 | 9.1 | ||

| 18 | 8.4 | ||

| 19 | Sicily | 7.5 | |

| 20 | 8.8 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 9.02 ± 2.94 | ||

| 21 | Almond | Apulia | 19.4 |

| 22 | 24.1 | ||

| 23 | 19.1 | ||

| 24 | 23.3 | ||

| 25 | 17.1 | ||

| 26 | 20 | ||

| 27 | Sicily | 12 | |

| 28 | 11.6 | ||

| 29 | 16 | ||

| 30 | 16.2 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 17.88 ± 4.18 | ||

| 31 | Eucalyptus | Apulia | 13 |

| 32 | 11.6 | ||

| 33 | 10.4 | ||

| 34 | Tuscany | 12.5 | |

| 35 | Sicily | 9.9 | |

| 36 | Calabria | 12.7 | |

| 37 | 10.2 | ||

| 38 | Lazio | 12.3 | |

| 39 | 11.8 | ||

| 40 | Sardinia | 12 | |

| Mean ± SD | 11.64 ± 1.10 | ||

| 41 | Coriander | Apulia | 6.9 |

| 42 | 6.7 | ||

| 43 | 6.6 | ||

| 44 | 9.8 | ||

| 45 | Marche | 6.9 | |

| 46 | 6.5 | ||

| 47 | Emilia Romagna | 8.4 | |

| 48 | 6.9 | ||

| 49 | Abruzzo | 7.8 | |

| 50 | 6.4 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 7.29 ± 1.08 | ||

| 51 | Cornflower | Apulia | 9.7 |

| 52 | 9.3 | ||

| 53 | 8.8 | ||

| 54 | 14.8 | ||

| 55 | Tuscany | 8.1 | |

| 56 | 10.1 | ||

| 57 | Lazio | 8.7 | |

| 58 | 9.9 | ||

| 59 | Marche | 13.8 | |

| 60 | 9.6 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 10.28 ± 2.22 | ||

| 61 | Thistle | Apulia | 8.9 |

| 62 | 8.1 | ||

| 63 | Calabria | 8.6 | |

| 64 | 7.9 | ||

| 65 | 8.5 | ||

| 66 | 8.9 | ||

| 67 | Sicily | 8.2 | |

| 68 | 8.7 | ||

| 69 | 8.3 | ||

| 70 | 8.8 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 8.49 ± 0.35 | ||

| 71 | Acacia | Apulia | 15 |

| 72 | 6.6 | ||

| 73 | Sardinia | 5.2 | |

| 74 | 7.2 | ||

| 75 | Tuscany | 6.9 | |

| 76 | 14.1 | ||

| 77 | Piedmont | 5.8 | |

| 78 | Abruzzo | 6.8 | |

| 79 | Veneto | 15.2 | |

| 80 | Campania | 5.9 | |

| Mean ± SD | 8.87 ± 4.12 | ||

| 81 | Citrus | Apulia | 7.7 |

| 82 | 6.9 | ||

| 83 | 4.7 | ||

| 84 | 4.6 | ||

| 85 | Basilicata | 4.5 | |

| 86 | 2.8 | ||

| 87 | Calabria | 0.4 | |

| 88 | 2.9 | ||

| 89 | Sicily | 6.7 | |

| 90 | 3.9 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 4.51 ± 2.2 | ||

| 91 | Honeydew | Abruzzo | 9.9 |

| 92 | Apulia | 5.9 | |

| 93 | 5.9 | ||

| 94 | Emilia Romagna | 5.7 | |

| 95 | Aosta Valley | 6.6 | |

| 96 | 5.5 | ||

| 97 | Trentino Alto Adige | 9.2 | |

| 98 | 5.7 | ||

| 99 | Tuscany | 6.2 | |

| 100 | 7.8 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 6.84 ± 1.58 | ||

| 101 | Multifloral | Apulia | 18.4 |

| 102 | 11 | ||

| 103 | 6.5 | ||

| 104 | 6.3 | ||

| 105 | Campania | 12.9 | |

| 106 | 7.8 | ||

| 107 | Calabria | 9.9 | |

| 108 | 10.4 | ||

| 109 | Emilia Romagna | 8.8 | |

| 110 | 7.2 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 9.92 ± 3.65 |

| Floral Origin | MGO |

|---|---|

| Citrus | 4.51 A |

| Acacia | 8.87 B |

| Coriander | 7.29 B |

| Honeydew | 6.84 B |

| Multifloral | 9.92 BC |

| Thistle | 8.49 BC |

| Thyme | 9.02 BC |

| Cornflower | 10.28 C |

| Eucalyptus | 11.64 C |

| Almond | 17.88 D |

| Sweet Cherry | 18.62 D |

| SEM 1 | 0.88 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Terio, V.; Bozzo, G.; Ceci, E.; Savarino, A.E.; Barrasso, R.; Di Pinto, A.; Mottola, A.; Marchetti, P.; Tantillo, G.; Bonerba, E. Methylglyoxal (MGO) in Italian Honey. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11020831

Terio V, Bozzo G, Ceci E, Savarino AE, Barrasso R, Di Pinto A, Mottola A, Marchetti P, Tantillo G, Bonerba E. Methylglyoxal (MGO) in Italian Honey. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(2):831. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11020831

Chicago/Turabian StyleTerio, Valentina, Giancarlo Bozzo, Edmondo Ceci, Alessandra Emilia Savarino, Roberta Barrasso, Angela Di Pinto, Anna Mottola, Patrizia Marchetti, Giuseppina Tantillo, and Elisabetta Bonerba. 2021. "Methylglyoxal (MGO) in Italian Honey" Applied Sciences 11, no. 2: 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11020831

APA StyleTerio, V., Bozzo, G., Ceci, E., Savarino, A. E., Barrasso, R., Di Pinto, A., Mottola, A., Marchetti, P., Tantillo, G., & Bonerba, E. (2021). Methylglyoxal (MGO) in Italian Honey. Applied Sciences, 11(2), 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11020831