Overcoming Alzheimer’s Disease Stigma by Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain Technologies

Abstract

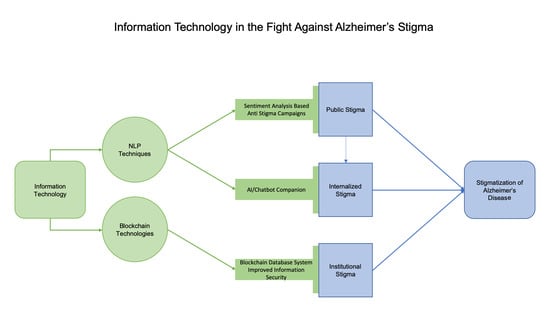

:1. Introduction

2. Utilizing Natural Language Processing to Fight Stigma

2.1. Social Media as a Propagator of and Protector from Stigma

2.2. Natural Language Processing in Stigma Research

2.3. Sentiment in Social Media

2.4. NLP in Chat-Bots/AI Companions

2.5. Natural Language Processing in AD Stigma Analysis & Research Direction

3. Utilizing Blockchain Technologies to Fight Stigma

3.1. Information Privacy and Stigma

3.2. Blockchain Technologies as a Means of Secure Data Storage

3.3. Potential Applications of Blockchain Technologies in the Healthcare Sector

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzheimer’s-Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s Disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 15, 321–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stites, S.D.; Milne, R.; Karlawish, J. Advances in Alzheimer’s imaging are changing the experience of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. (Amst.) 2018, 10, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Harkins, K.; Cary, M.; Sankar, P.; Karlawish, J. The relative contributions of disease label and disease prognosis to Alzheimer’s stigma: A vignette-based experiment. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 143, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolley, D.J.; Benbow, S.M. Stigma and Alzheimer’s disease: Causes, consequences and a constructive approach. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2000, 54, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Batsch, N.L.; Mittelman, M.S. Overcoming the Stigma of Dementia; World Alzheimer Report 2012; Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI): London, UK, 2012; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Stites, S.D.; Rubright, J.D.; Karlawish, J. What features of stigma do the public most commonly attribute to Alzheimer’s disease dementia? Results of a survey of the U.S. general public. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s-Association. Overcoming Stigma. Available online: https://alz.org/help-support/i-have-alz/overcoming-stigma (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Rozenblum, R.; Bates, D.W. Patient-centred healthcare, social media and the internet: The perfect storm? BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 22, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greene, J.A.; Choudhry, N.K.; Kilabuk, E.; Shrank, W.H. Online social networking by patients with diabetes: A qualitative evaluation of communication with Facebook. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crabtree, J.W.; Haslam, S.A.; Postmes, T.; Haslam, C. Mental health support groups, stigma, and self-esteem: Positive and negative implications of group identification. J. Soc. Issues 2010, 66, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.; Ayers, S.; Drey, N. A Thematic Analysis of Stigma and Disclosure for Perinatal Depression on an Online Forum. JMIR Ment. Health 2016, 3, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, A.; Kirakowski, J. Online support groups for mental health: A space for challenging self-stigma or a means of social avoidance? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 32, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshua-Katz, D. Online Stigma Resistance in the Pro-Ana Community. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.R.; Chung, P.H.; Bedford, T.; Navrazhina, K. Facebook as a Site for Negative Age Stereotypes. Gerontologist 2013, 54, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D.; Murphy, T.E.; Gill, T.M. Association between positive age stereotypes and recovery from disability in older persons. JAMA 2012, 308, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eysenbach, G. Infodemiology and infoveillance: Framework for an emerging set of public health informatics methods to analyze search, communication and publication behavior on the Internet. J. Med. Internet Res. 2009, 11, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roccetti, M.; Marfia, G.; Salomoni, P.; Prandi, C.; Zagari, R.M.; Gningaye Kengni, F.L.; Bazzoli, F.; Montagnani, M. Attitudes of Crohn’s Disease Patients: Infodemiology Case Study and Sentiment Analysis of Facebook and Twitter Posts. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2017, 3, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B. Sentiment Analysis Mining Opinions, Sentiments, and Emotions; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kreimeyer, K.; Foster, M.; Pandey, A.; Arya, N.; Halford, G.; Jones, S.F.; Forshee, R.; Walderhaug, M.; Botsis, T. Natural language processing systems for capturing and standardizing unstructured clinical information: A systematic review. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017, 73, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhalishahi, S.; Miotto, R.; Dudley, J.T.; Lavelli, A.; Rinaldi, F.; Osmani, V. Natural Language Processing of Clinical Notes on Chronic Diseases: Systematic Review. JMIR Med. Inform. 2019, 7, e12239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Xie, H.; Wang, F.L.; Liu, Z.; Xu, J.; Hao, T. A bibliometric analysis of natural language processing in medical research. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denecke, K.; Deng, Y. Sentiment analysis in medical settings: New opportunities and challenges. Artif. Intell. Med. 2015, 64, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, E.E.; Prestin, A.; Gaysynsky, A.; Galica, K.; Rinker, R.; Graff, K.; Chou, W.Y. “Obesity is the New Major Cause of Cancer”: Connections Between Obesity and Cancer on Facebook and Twitter. J. Cancer Educ. 2016, 31, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohil, S.; Vuik, S.; Darzi, A. Sentiment Analysis of Health Care Tweets: Review of the Methods Used. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2018, 4, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofean, M.; Smith, M. Sentiment analysis on smoking in social networks. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2013, 192, 1118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gabarron, E.; Dorronzoro, E.; Rivera-Romero, O.; Wynn, R. Diabetes on Twitter: A Sentiment Analysis. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2019, 13, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.Y.; Prestin, A.; Kunath, S. Obesity in social media: A mixed methods analysis. Transl. Behav. Med. 2014, 4, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zoppei, S.; Lasalvia, A. Anti stigma campaigns: Really useful and effective? A critical review of the anti-stigma initiatives conducted in Italy. Riv. Psichiatr. 2011, 46, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A.; Grundy, E.; Farquhar, M. Changes in network composition among the very old living in inner London. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 1995, 10, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertel, K.A.; Glymour, M.M.; Berkman, L.F. Effects of social integration on preserving memory function in a nationally representative US elderly population. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.; Comas-Herrera, A.; Grundy, E. Social Isolation and Memory Decline in Later-life. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedler, B.; Crapser, J.; McCullough, L. One is the deadliest number: The detrimental effects of social isolation on cerebrovascular diseases and cognition. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 129, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perissinotto, C.M.; Stijacic Cenzer, I.; Covinsky, K.E. Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gustafson, D.H., Sr.; McTavish, F.; Gustafson, D.H., Jr.; Mahoney, J.E.; Johnson, R.A.; Lee, J.D.; Quanbeck, A.; Atwood, A.K.; Isham, A.; Veeramani, R.; et al. The effect of an information and communication technology (ICT) on older adults’ quality of life: Study protocol for a randomized control trial. Trials 2015, 16, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abdi, J.; Al-Hindawi, A.; Ng, T.; Vizcaychipi, M.P. Scoping review on the use of socially assistive robot technology in elderly care. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robinson, H.; Macdonald, B.; Kerse, N.; Broadbent, E. The psychosocial effects of a companion robot: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, M.R.; Willoughby, L.M.; Banks, W.A. Animal-assisted therapy and loneliness in nursing homes: Use of robotic versus living dogs. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2008, 9, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, K.; Shibata, T. Living with Seal Robots in a Care House-Evaluations of Social and Physiological Influences. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Beijing, China, 9–15 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, S.; Houston, S.; Qin, H.; Tague, C.; Studley, J. The Utilization of Robotic Pets in Dementia Care. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2017, 55, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mervin, M.C.; Moyle, W.; Jones, C.; Murfield, J.; Draper, B.; Beattie, E.; Shum, D.H.K.; O’Dwyer, S.; Thalib, L. The Cost-Effectiveness of Using PARO, a Therapeutic Robotic Seal, to Reduce Agitation and Medication Use in Dementia: Findings from a Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, W.; Jones, C.J.; Murfield, J.E.; Thalib, L.; Beattie, E.R.A.; Shum, D.K.H.; O’Dwyer, S.T.; Mervin, M.C.; Draper, B.M. Use of a Robotic Seal as a Therapeutic Tool to Improve Dementia Symptoms: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vardoulakis, L.P.; Ring, L.; Barry, B.; Sidner, C.L.; Bickmore, T. Designing relational agents as long term social companions for older adults. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 12–14 September 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Shaked, N.A. Avatars and virtual agents - relationship interfaces for the elderly. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 2017, 4, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Cristancho-Lacroix, V.; Fassert, C.; Faucounau, V.; de Rotrou, J.; Rigaud, A.-S. The Attitudes and Perceptions of Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment Toward an Assistive Robot. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016, 35, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, M.M.A.; Allouch, S.B.; Klamer, T. Sharing a life with Harvey: Exploring the acceptance of and relationship-building with a social robot. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, H.; Mollahosseini, A.; Lane, J.T.; Mahoor, M.H. A pilot study on using an intelligent life-like robot as a companion for elderly individuals with dementia and depression. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE-RAS 17th International Conference on Humanoid Robotics (Humanoids), Birmingham, UK, 15–17 November 2017; pp. 541–546. [Google Scholar]

- McColl, D.; Louie, W.-Y.G.; Nejat, G. Brian 2.1: A socially assistive robot for the elderly and cognitively impaired. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2013, 20, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, C.D.; Breazeal, C. Sociable robot systems for real-world problems. In Proceedings of the ROMAN 2005 IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Nashville, TN, USA, 13–15 August 2005; pp. 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, C.D. Sociable Robots: The Role of Presence and Task in Human-Robot Interaction. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambride, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gouaillier, D.; Hugel, V.; Blazevic, P.; Kilner, C.; Monceaux, J.; Lafourcade, P.; Marnier, B.; Serre, J.; Maisonnier, B. The nao humanoid: A combination of performance and affordability. arXiv 2008, arXiv:0807.3223. [Google Scholar]

- Zakipour, M.; Meghdari, A.; Alemi, M. RASA: A low-cost upper-torso social robot acting as a sign language teaching assistant. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of International Conference on Social Robotics, Kansas City, MO, USA, 1–3, November 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 630–639. [Google Scholar]

- Korchut, A.; Szklener, S.; Abdelnour, C.; Tantinya, N.; Hernandez-Farigola, J.; Ribes, J.C.; Skrobas, U.; Grabowska-Aleksandrowicz, K.; Szczesniak-Stanczyk, D.; Rejdak, K. Challenges for Service Robots-Requirements of Elderly Adults with Cognitive Impairments. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradwell, H.L.; Edwards, K.J.; Winnington, R.; Thill, S.; Jones, R.B. Companion robots for older people: Importance of user-centred design demonstrated through observations and focus groups comparing preferences of older people and roboticists in South West England. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oscar, N.; Fox, P.A.; Croucher, R.; Wernick, R.; Keune, J.; Hooker, K. Machine Learning, Sentiment Analysis, and Tweets: An Examination of Alzheimer’s Disease Stigma on Twitter. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 72, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilicoglu, H.; Peng, Z.; Tafreshi, S.; Tran, T.; Rosemblat, G.; Schneider, J. Confirm or refute?: A comparative study on citation sentiment classification in clinical research publications. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 91, 103123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Hinton, L.; Tran, C.; Hinton, D.; Barker, J.C. Reexamining the relationships among dementia, stigma, and aging in immigrant Chinese and Vietnamese family caregivers. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2008, 23, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arias, J.J.; Karlawish, J. Confidentiality in preclinical Alzheimer disease studies: When research and medical records meet. Neurology 2014, 82, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kruse, C.S.; Frederick, B.; Jacobson, T.; Monticone, D.K. Cybersecurity in healthcare: A systematic review of modern threats and trends. Technol. Health Care 2017, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- HIPAA-Journal. October 2019 Healthcare Data Breach Report. In Healthcare Cybersecurity; HIPAA Journal: Encino, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Agaku, I.T.; Adisa, A.O.; Ayo-Yusuf, O.A.; Connolly, G.N. Concern about security and privacy, and perceived control over collection and use of health information are related to withholding of health information from healthcare providers. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2014, 21, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-To-Peer Electronic Cash System. 2008. Available online: https://nakamotoinstitute.org/bitcoin/ (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Agbo, C.C.; Mahmoud, Q.H.; Eklund, J.M. Blockchain Technology in Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2019, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kuo, T.T.; Kim, H.E.; Ohno-Machado, L. Blockchain distributed ledger technologies for biomedical and health care applications. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2017, 24, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yli-Huumo, J.; Ko, D.; Choi, S.; Park, S.; Smolander, K. Where Is Current Research on Blockchain Technology?-A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cichosz, S.L.; Stausholm, M.N.; Kronborg, T.; Vestergaard, P.; Hejlesen, O. How to Use Blockchain for Diabetes Health Care Data and Access Management: An Operational Concept. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2019, 13, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.V. Blockchain applications for healthcare data management. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2019, 25, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, L.; Koo, M. Blockchain For Health Data and Its Potential Use in Health IT and Health Care Related Research. In ONC/NIST Use of Blockchain for Healthcare and Research Workshop; ONC/NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, W.J.; Catalini, C. Blockchain Technology for Healthcare: Facilitating the Transition to Patient-Driven Interoperability. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.; Vyshnavi, A.H.; Srinivasan, C.; Namboori, P.K. Healthcare security using blockchain for pharmacogenomics. Journal of International Pharmaceutical Research. 2019, 46, 529–533. [Google Scholar]

- Lunshof, J.E.; Chadwick, R.; Vorhaus, D.B.; Church, G.M. From genetic privacy to open consent. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtis, L.C.; Regele, O.B.; Wright, J.M.; Jones, G.B. Digital biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: The mobile/wearable devices opportunity. NPJ Digit. Med. 2019, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, M.; Amatniek, J.; Carrillo, M.C.; Cedarbaum, J.M.; Hendrix, J.A.; Miller, B.B.; Robillard, J.M.; Rice, J.J.; Soares, H.; Tome, M.B.; et al. Digital technologies as biomarkers, clinical outcomes assessment, and recruitment tools in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. Alzheimer’s Dement. (N. Y.) 2018, 4, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Papapetropoulos, S.; Xiong, M.; Kieburtz, K. The First Frontier: Digital Biomarkers for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Digit. Biomark. 2017, 1, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torous, J.; Rodriguez, J.; Powell, A. The New Digital Divide For Digital BioMarkers. Digit. Biomark. 2017, 1, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beach, S.; Schulz, R.; Downs, J.; Matthews, J.; Barron, B.; Seelman, K. Disability, age, and informational privacy attitudes in quality of life technology applications: Results from a national web survey. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. (TACCESS) 2009, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, M.; Maguire Truong, A.; Bot, B.M.; Wilbanks, J.; Suver, C.; Mangravite, L.M. Formative Evaluation of Participant Experience With Mobile eConsent in the App-Mediated Parkinson mPower Study: A Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017, 5, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.O.; Yoo, S.G.; Cazares, M.F. A comprehensive study of IOT for Alzheimer’s disease. In Multi Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, MCCSIS 2019-Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Health; IADIS Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Lok, D.; Bartrem, K.; Chiu, G. Blockchain-Enabled Multisensor Clinical Laboratory Information System. Asian J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 5, 232–240. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pilozzi, A.; Huang, X. Overcoming Alzheimer’s Disease Stigma by Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain Technologies. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10030183

Pilozzi A, Huang X. Overcoming Alzheimer’s Disease Stigma by Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain Technologies. Brain Sciences. 2020; 10(3):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10030183

Chicago/Turabian StylePilozzi, Alexander, and Xudong Huang. 2020. "Overcoming Alzheimer’s Disease Stigma by Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain Technologies" Brain Sciences 10, no. 3: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10030183

APA StylePilozzi, A., & Huang, X. (2020). Overcoming Alzheimer’s Disease Stigma by Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain Technologies. Brain Sciences, 10(3), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10030183