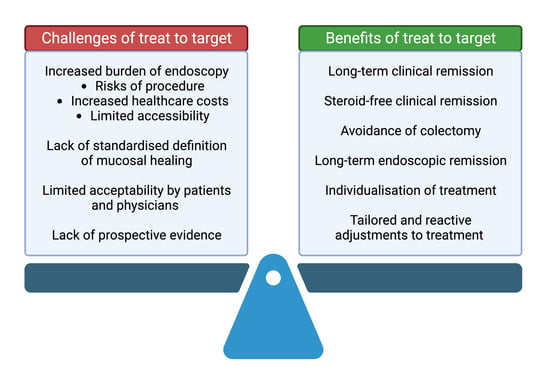

Benefits and Challenges of Treat-to-Target in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. What Is Treat-to-Target and How Do We Achieve It?

3. Evidence Supporting Mucosal Healing

4. Challenges of a Treat-to-Target Approach

4.1. Need for Repeated Endoscopy

4.2. Lack of Universal and Validated Definition of Mucosal Healing

4.3. Evidence of Treat-to-Target Strategies Incorporating Serial Endoscopy Is Largely Retrospective

4.4. Feasibility of Tight Monitoring Utilising a T2T Strategy in Real-World Practice

| Study, Year, Design | Population (No., UC/CD), Follow-Up | Interval of Objective Assessment | Proportion of Patients Completing Assessment at Relative Intervals | Outcome Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Khoury et al., 2021, retrospective observational [41] | 428 pts, 338 (79%) CD, 90 (21%) UC | Three-monthly to 12 months | At 3 months follow-up Clinical: 95.5% CD, 94.3% UC CRP: 70.6% CD, 64% UC Fcal: 25.4% CD, 33.3% UC At 6 months follow-up Clinical: 90.1% CD, 83.8% UC CRP: 54% CD, 52.7% UC Fcal: 24.6% CD, 13.5% UC At 12 months follow-up: Clinical: 95.6% CD, 88.5% UC CRP: 55.2% CD, 51.9% UC Fcal: 29% CD, 19.2% UC | Clinical remission at 12 months associated with: Combined adherence at 3 months vs. non-adherence in CD, 63.6% vs. 43.3%, p = 0.001. Combined adherence at 3 months vs. non-adherence in UC, 43.9% vs. 20.0%, p = 0.001. |

| Wetwittayakhlang et al., 2022, prospective observational [39] | 104 pts, 82 (79%) CD, 22 (21%) UC, consecutively recruited | Three-monthly to 12 months | At 3 months follow-up Clinical: 87.7% CD, 90.9% UC CRP: 54.9% CD, 50% UC Fcal: 23.5% CD, 18.2% UC At 6 months follow-up Clinical: 83.8% CD, 90% UC CRP: 46.3% CD, 50% UC Fcal: 31.3% CD, 25% UC At 12 months follow-up: Clinical: 81.3% CD, 76.5% UC CRP: 37.3% CD, 29.4% UC Fcal: 22.7% CD, 17.6% UC Endoscopy in first 6 months: 21.5% CD, 40.9% UC Endoscopy in second 6 months: 26.3% CD, 34.6% UC | Clinical remission at 12 months associated with: Early combined adherence vs. non-adherence in CD (70.2% vs. 29.8%, p = 0.007). Earlier dose optimisation of adalimumab associated with: Early combined adherence at 3 and 6 months in CD and UC (log-rank < 0.001). |

| Click et al., 2022, data from prospective longitudinal cohort [40] | 525 pts, 375 (71.4%) CD, 150 (28.6%) UC | Within 12 weeks prior to dose escalation or cessation of biologic therapy | Prior to escalation of therapy (n = 292) ≥1 measure: 67.9% CD, 66.32% UC ≥2 measures: 33.5% CD, 42.9% UC CRP: 39.1% CD, 54.5% UC Fcal: 5.6% CD, 13% UC Endoscopy: 26.5% CD, 23.4% UC Prior to discontinuation of therapy (n = 233) ≥1 measure: 79.4% CD, 79.5% UC ≥2 measures: 44.4% CD, 38.4% UC CRP: 46.3% CD, 35.6% UC Fcal: 6.9% CD, 8.2% UC Endoscopy: 33.1% CD, 39.7% UC | N/A |

4.5. Effect on Therapeutic Decision Making

4.6. Acceptability and Real-World Uptake

4.7. The need to Specifically Address Psychological Co-Morbidity in IBD

5. Solutions to the Challenges

5.1. Non-Invasive Objective Monitoring of Disease Activity—Biomarkers

5.2. Non-Invasive Objective Monitoring of Disease Activity—IUS

5.3. Individualisation of Treatments

6. Conclusions and Future Needs

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Torres, J.; Billioud, V.; Sachar, D.B.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Colombel, J.F. Ulcerative colitis as a progressive disease: The forgotten evidence. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.; Mehandru, S.; Colombel, J.F.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1741–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungaro, R.; Colombel, J.-F.; Lissoos, T.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. A Treat-to-Target Update in Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2019, 114, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Ricciuto, A.; Lewis, A.; D’Amico, F.; Dhaliwal, J.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bettenworth, D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; et al. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombel, J.F.; D’Haens, G.; Lee, W.J.; Petersson, J.; Panaccione, R. Outcomes and Strategies to Support a Treat-to-target Approach in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2020, 14, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonczi, L.; Bessissow, T.; Lakatos, P.L. Disease monitoring strategies in inflammatory bowel diseases: What do we mean by “tight control”? World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 6172–6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangnoo, S.K.; Sethi, B.; Sahay, R.K.; John, M.; Ghosal, S.; Sharma, S.K. Treat-to-target trials in diabetes. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 18, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmester, G.R.; Pope, J.E. Novel treatment strategies in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2017, 389, 2338–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atar, D.; Birkeland, K.I.; Uhlig, T. ‘Treat to target’: Moving targets from hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes to rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 629–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Sandborn, W.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; Bemelman, W.; Bryant, R.V.; D’Haens, G.; Dotan, I.; Dubinsky, M.; Feagan, B.; et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 1324–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombel, J.F.; Narula, N.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Management Strategies to Improve Outcomes of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 351–361.e355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, B.G.; Sandborn, W.J.; Ruel, J.; Feagan, B.G.; Sands, B.E.; Colombel, J.F. Converging goals of treatment of inflammatory bowel disease from clinical trials and practice. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 37–51.e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, E.C.; Elias, S.G.; Minderhoud, I.M.; van der Veen, J.J.; Baert, F.J.; Laharie, D.; Bossuyt, P.; Bouhnik, Y.; Buisson, A.; Lambrecht, G.; et al. Systematic Review and External Validation of Prediction Models Based on Symptoms and Biomarkers for Identifying Endoscopic Activity in Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 1704–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulai, P.S.; Feagan, B.G.; Sands, B.E.; Chen, J.; Lasch, K.; Lirio, R.A. Prognostic Value of Fecal Calprotectin to Inform Treat-to-Target Monitoring in Ulcerative Colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 456–466.e457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frimor, C.; Kjeldsen, J.; Ainsworth, M. Treatment to target in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. What is the evidence? Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.C.; Colombel, J.F.; Sands, B.E.; Narula, N. Mucosal Healing Is Associated With Improved Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 1245–1255.e1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.C.; Colombel, J.F.; Sands, B.E.; Narula, N. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Mucosal healing is associated with improved long-term outcomes in Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 43, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombel, J.F.; Rutgeerts, P.; Reinisch, W.; Esser, D.; Wang, Y.; Lang, Y.; Marano, C.W.; Strauss, R.; Oddens, B.J.; Feagan, B.G.; et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrante, M.; Colombel, J.F.; Sandborn, W.J.; Reinisch, W.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Kornbluth, A.; Rachmilewitz, D.; Lichtiger, S.; D’Haens, G.R.; van der Woude, C.J.; et al. Validation of endoscopic activity scores in patients with Crohn’s disease based on a post hoc analysis of data from SONIC. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 978–986.e975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, F.; Fidder, H.; Ferrante, M.; Noman, M.; Arijs, I.; Van Assche, G.; Hoffman, I.; Van Steen, K.; Vermeire, S.; Rutgeerts, P. Mucosal healing predicts long-term outcome of maintenance therapy with infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frøslie, K.F.; Jahnsen, J.; Moum, B.A.; Vatn, M.H. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: Results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Af Björkesten, C.G.; Nieminen, U.; Sipponen, T.; Turunen, U.; Arkkila, P.; Färkkilä, M. Mucosal healing at 3 months predicts long-term endoscopic remission in anti-TNF-treated luminal Crohn’s disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakase, H.; Esaki, M.; Hirai, F.; Kobayashi, T.; Matsuoka, K.; Matsuura, M.; Naganuma, M.; Saruta, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Uchino, M.; et al. Treatment escalation and de-escalation decisions in Crohn’s disease: Delphi consensus recommendations from Japan, 2021. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 58, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohra, A.; Mohamed, G.; Vasudevan, A.; Lewis, D.; Van Langenberg, D.R.; Segal, J.P. The Utility of Faecal Calprotectin, Lactoferrin and Other Faecal Biomarkers in Discriminating Endoscopic Activity in Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, C.Y.; Katz, S. Clinical implications of ageing for the management of IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, B.; Scarozza, P.; Giannarelli, D.; Sena, G.; Mossa, M.; Lolli, E.; Calabrese, E.; Biancone, L.; Grasso, E.; Di Iorio, L.; et al. Efficacy and tolerability of very low-volume bowel preparation in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravina, A.G.; Pellegrino, R.; Romeo, M.; Palladino, G.; Cipullo, M.; Iadanza, G.; Olivieri, S.; Zagaria, G.; De Gennaro, N.; Santonastaso, A.; et al. Quality of bowel preparation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing colonoscopy: What factors to consider? World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 15, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuitton, L.; Marteau, P.; Sandborn, W.J.; Levesque, B.G.; Feagan, B.; Vermeire, S.; Danese, S.; D’Haens, G.; Lowenberg, M.; Khanna, R.; et al. IOIBD technical review on endoscopic indices for Crohn’s disease clinical trials. Gut 2016, 65, 1447–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Vashist, N.; Samaan, M.; Mosli, M.H.; Parker, C.E.; MacDonald, J.K.; Nelson, S.A.; Zou, G.Y.; Feagan, B.G.; Khanna, R.; Jairath, V. Endoscopic scoring indices for evaluation of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 1, Cd011450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscido, A.; Valvano, M.; Stefanelli, G.; Capannolo, A.; Castellini, C.; Onori, E.; Ciccone, A.; Vernia, F.; Latella, G. Systematic review and meta-analysis: The advantage of endoscopic Mayo score 0 over 1 in patients with ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Jangi, S.; Dulai, P.S.; Boland, B.S.; Prokop, L.J.; Jairath, V.; Feagan, B.G.; Sandborn, W.J.; Singh, S. Incremental Benefit of Achieving Endoscopic and Histologic Remission in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1262–1275.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klenske, E.; Bojarski, C.; Waldner, M.; Rath, T.; Neurath, M.F.; Atreya, R. Targeting mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease: What the clinician needs to know. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2019, 12, 1756284819856865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignass, A.; Rath, S.; Kleindienst, T.; Stallmach, A. Review article: Translating STRIDE-II into clinical reality—Opportunities and challenges. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 58, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouguen, G.; Levesque, B.G.; Pola, S.; Evans, E.; Sandborn, W.J. Feasibility of endoscopic assessment and treating to target to achieve mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguen, G.; Levesque, B.G.; Pola, S.; Evans, E.; Sandborn, W.J. Endoscopic assessment and treating to target increase the likelihood of mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meade, S.; Routledge, E.; Sharma, E.; Honap, S.; Zeki, S.; Ray, S.; Anderson, S.H.C.; Sanderson, J.; Mawdsley, J.; Irving, P.M.; et al. How achievable are STRIDE-II treatment targets in real-world practice and do they predict long-term treatment outcomes? Frontline Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, R.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, B.L.; Zhang, S.H.; Feng, R.; He, Y.; Zeng, Z.R.; Ben-Horin, S.; Chen, M.H. Factors associated with the achievement of mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease: The benefit of endoscopic monitoring in treating to target. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2017, 10, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Af Björkesten, C.G.; Nieminen, U.; Turunen, U.; Arkkila, P.E.; Sipponen, T.; Färkkilä, M.A. Endoscopic monitoring of infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetwittayakhlang, P.; Golovics, P.A.; Khoury, A.A.; Ganni, E.; Hahn, G.D.; Cohen, A.; Wyse, J.; Bradette, M.; Bessissow, T.; Afif, W.; et al. Adherence to Objective Therapeutic Monitoring and Outcomes in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease with Adalimumab Treatment. A Real-world Prospective Study. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 2022, 31, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Click, B.; Barnes, E.L.; Cohen, B.L.; Sands, B.E.; Hanson, J.S.; Rubin, D.T.; Dubinsky, M.C.; Regueiro, M.; Gazis, D.; Crawford, J.M.; et al. Objective disease activity assessment and therapeutic drug monitoring prior to biologic therapy changes in routine inflammatory bowel disease clinical practice: TARGET-IBD. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khoury, A.; Xiao, Y.; Golovics, P.A.; Kohen, R.; Afif, W.; Wild, G.; Friedman, G.; Galiatsatos, P.; Hilzenrat, N.; Szilagyi, A.; et al. Assessing adherence to objective disease monitoring and outcomes with adalimumab in a real-world IBD cohort. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dignass, A.U.; Paridaens, K.; Al Awadhi, S.; Begun, J.; Cheon, J.H.; Fullarton, J.R.; Louis, E.; Magro, F.; Marquez, J.R.; Moschen, A.R.; et al. Multinational evaluation of clinical decision-making in the treatment and management of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 57, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, N.M.; Cohen, N.A.; Rubin, D.T. Treat-to-target and sequencing therapies in Crohn’s disease. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2022, 10, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, O.B.; Donnell, S.O.; Stempak, J.M.; Steinhart, A.H.; Silverberg, M.S. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring to Guide Infliximab Dose Adjustment is Associated with Better Endoscopic Outcomes than Clinical Decision Making Alone in Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Del Tedesco, E.; Marotte, H.; Rinaudo-Gaujous, M.; Moreau, A.; Phelip, J.M.; Genin, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Roblin, X. Therapeutic drug monitoring of infliximab and mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 2568–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S.R.; Bernardo, S.; Simões, C.; Gonçalves, A.R.; Valente, A.; Baldaia, C.; Moura Santos, P.; Correia, L.A.; Tato Marinho, R. Proactive Infliximab Drug Monitoring Is Superior to Conventional Management in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vande Casteele, N.; Ferrante, M.; Van Assche, G.; Ballet, V.; Compernolle, G.; Van Steen, K.; Simoens, S.; Rutgeerts, P.; Gils, A.; Vermeire, S. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 1320–1329.e1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Haens, G.; Vermeire, S.; Lambrecht, G.; Baert, F.; Bossuyt, P.; Pariente, B.; Buisson, A.; Bouhnik, Y.; Filippi, J.; Vander Woude, J.; et al. Increasing Infliximab Dose Based on Symptoms, Biomarkers, and Serum Drug Concentrations Does Not Increase Clinical, Endoscopic, and Corticosteroid-Free Remission in Patients With Active Luminal Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1343–1351.e1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinger, C.; Carbonell, J.; Kane, J.; Omer, M.; Ford, A.C. Acceptability of a ‘treat to target’ approach in inflammatory bowel disease to patients in clinical remission. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021, 12, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.V.; Costello, S.P.; Schoeman, S.; Sathananthan, D.; Knight, E.; Lau, S.Y.; Schoeman, M.N.; Mountifield, R.; Tee, D.; Travis, S.P.L.; et al. Limited uptake of ulcerative colitis “treat-to-target” recommendations in real-world practice. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 33, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, P.; Barrett, K.; Nijher, M.; de Lusignan, S. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in people with inflammatory bowel disease and associated healthcare use: Population-based cohort study. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2021, 24, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graff, L.A.; Geist, R.; Kuenzig, M.E.; Benchimol, E.I.; Kaplan, G.G.; Windsor, J.W.; Bitton, A.; Coward, S.; Jones, J.L.; Lee, K.; et al. The 2023 Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada: Mental Health and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Can Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2023, 6, S64–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberio, B.; Zamani, M.; Black, C.J.; Savarino, E.V.; Ford, A.C. Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuendorf, R.; Harding, A.; Stello, N.; Hanes, D.; Wahbeh, H. Depression and anxiety in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 87, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, A.; Mazzarella, C.; Dallio, M.; Romeo, M.; Pellegrino, R.; Durante, T.; Romano, M.; Loguercio, C.; Di Mauro, M.; Federico, A.; et al. The Lesson from the First Italian Lockdown: Impacts on Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Quality in Patients with Remission of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials 2022, 17, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.L.; Nguyen, G.C.; Benchimol, E.I.; Bernstein, C.N.; Bitton, A.; Kaplan, G.G.; Murthy, S.K.; Lee, K.; Cooke-Lauder, J.; Otley, A.R. The Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada 2018: Quality of Life. J. Can Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2019, 2, S42–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubinsky, M.C.; Dotan, I.; Rubin, D.T.; Bernauer, M.; Patel, D.; Cheung, R.; Modesto, I.; Latymer, M.; Keefer, L. Burden of comorbid anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic literature review. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 15, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.L.; Kochar, B.; Long, M.D.; Kappelman, M.D.; Martin, C.F.; Korzenik, J.R.; Crockett, S.D. Modifiable Risk Factors for Hospital Readmission Among Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Nationwide Database. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegretti, J.R.; Borges, L.; Lucci, M.; Chang, M.; Cao, B.; Collins, E.; Vogel, B.; Arthur, E.; Emmons, D.; Korzenik, J.R. Risk Factors for Rehospitalization Within 90 Days in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2583–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrieri, P.; Cicala, M.; Ribolsi, M. Psychological distress in inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 17, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.P.; Bolin, L.P.; Crane, P.B.; Crandell, J. Non-pharmacological Interventions for Anxiety and Depression in Adults With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 538741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lores, T.; Goess, C.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Collins, K.L.; Burke, A.L.J.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Delfabbro, P.; Andrews, J.M. Integrated Psychological Care is Needed, Welcomed and Effective in Ambulatory Inflammatory Bowel Disease Management: Evaluation of a New Initiative. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 13, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depont, F.; Berenbaum, F.; Filippi, J.; Le Maitre, M.; Nataf, H.; Paul, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Thibout, E. Interventions to Improve Adherence in Patients with Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Disorders: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravina, A.G.; Pellegrino, R.; Palladino, G.; Mazzarella, C.; Federico, P.; Arboretto, G.; D’Onofrio, R.; Olivieri, S.; Zagaria, G.; Durante, T.; et al. Targeting the gut-brain axis for therapeutic adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A review on the role of psychotherapy. Brain-Appar. Commun. J. Bacomics. 2023, 2, 2181101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C. Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 714057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombel, J.F.; Panaccione, R.; Bossuyt, P.; Lukas, M.; Baert, F.; Vaňásek, T.; Danalioglu, A.; Novacek, G.; Armuzzi, A.; Hébuterne, X.; et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn’s disease (CALM): A multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 2779–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.C.; Huang, V.W.; Bourdages, R.; Fedorak, R.N.; Reinhard, C.; Leung, Y.; Bressler, B.; Rosenfeld, G. IBDoc Canadian User Performance Evaluation. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.-T.; Chen, N.; Xu, J.; Goyal, H.; Wu, Z.-Q.; Zhang, J.-X.; Xu, H.-G. Diagnostic Accuracy of Fecal Calprotectin for Predicting Relapse in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancey, S.; Fumery, M.; Faure, M.; Boschetti, G.; Gay, C.; Milot, L.; Roblin, X. Use of imaging modalities for decision-making in inflammatory bowel disease. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2023, 16, 17562848231151293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ani, A.H.; Vaughan, R.; Christensen, B.; Bryant, R.V.; Novak, K.L. Treat to transmural healing: How to incorporate intestinal ultrasound into the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, 20211174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bots, S.; Nylund, K.; Löwenberg, M.; Gecse, K.; Gilja, O.H.; D’Haens, G. Ultrasound for Assessing Disease Activity in IBD Patients: A Systematic Review of Activity Scores. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2018, 12, 920–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allocca, M.; Fiorino, G.; Bonifacio, C.; Furfaro, F.; Gilardi, D.; Argollo, M.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Comparative Accuracy of Bowel Ultrasound Versus Magnetic Resonance Enterography in Combination With Colonoscopy in Assessing Crohn’s Disease and Guiding Clinical Decision-making. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2018, 12, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodsall, T.M.; Nguyen, T.M.; Parker, C.E.; Ma, C.; Andrews, J.M.; Jairath, V.; Bryant, R.V. Systematic Review: Gastrointestinal Ultrasound Scoring Indices for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojic, D.; Bodger, K.; Travis, S. Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: New Data. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2017, 11, S576–S585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, V.; Limketkai, B.N.; Sauk, J.S. IBD in the Elderly: Management Challenges and Therapeutic Considerations. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2019, 21, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Pardi, D.S. Inflammatory bowel disease of the elderly: Frequently asked questions (FAQs). Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 1889–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Boland, B.S.; Jess, T.; Moore, A.A. Management of inflammatory bowel diseases in older adults. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study, Year, Design | Population | Definition of MH, Proportion of pts | Outcomes Assessed | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term disease control | ||||

| Shah et al., 2016, meta-analysis of 13 prospective studies [16] | 2073 pts with active UC | Multiple definitions among included studies | Long-term CR, long-term defined as ≥52 weeks post treatment and ≥6 months post assessment of MH | pOR of 4.50 (95% CI, 2.12–9.52; p < 0.0001) for achieving long-term CR in patients achieving MH compared to those not |

| Shah et al., 2016, meta-analysis of 12 prospective studies [17] | 673 pts with active CD | Multiple definitions among included studies | Long-term CR, long-term defined as ≥50 weeks from study outset | pOR of 2.80 (95% CI, 1.91–4.10; p < 0.00001) for achieving long-term CR in patients achieving MH vs. those not |

| Colombel et al., 2011, retrospective analysis of previous RCT’s [18] | 728 UC pts with MES ≥ 2, treated with IFX or placebo | MES | CR at week 30, CR at week 54 | Lower MES at week 8 was associated with increased likelihood of CR at week 30, 71% MES 0, 51% MES 1, 23% MES 2, 9.7% MES 3, p < 0.0001 and week 54, 73% MES 0, 47% MES 1, 24% MES 2, 10% MES 3, p < 0.0001 among IFX-treated patients |

| Ferrante et al., 2013 [19] | 172 pts with CD treated with IFX, AZA, or both | MH: absence of ulcers Present in: 48% of patients at week 26 of treatment | CS-free CR at week 50 | MH at week 26 was associated with CS-free CR at week 50 with 56% sensitivity, 65% specificity, PLR of 1.60, and NLR of 0.67. |

| Avoidance of surgery | ||||

| Shah et al., 2016, meta-analysis of 13 prospective studies [16] | 2073 pts with active UC | Multiple definitions among included studies | Avoidance of colectomy at ≥52 weeks post treatment commencement and ≥6 months post finding of MH | pOR of 4.15 (95% CI, 2.53–6.81; p < 0.00001) for avoiding colectomy |

| Colombel et al., 2011, retrospective analysis of previous RCT’s [18] | 728 UC pts with MES ≥ 2, treated with IFX or placebo | MES | Avoidance of colectomy at 54 weeks | Lower MES at week 8 among IFX-treated patients associated with increased likelihood of avoiding colectomy, 95% MES 0, 95% MES 1, 83% MES 2, 80% MES 3, p = 0.0004 |

| Schnitzler et al., 2009, retrospective observational cohort study [20] | 214 CD pts on long-term IFX treatment with endoscopy before and during IFX therapy | Complete MH: absence of ulceration in patients who had ulcerations at baseline—present in 83 pts (45.4%) Partial MH: clear endoscopic improvement but with ulceration present—present in 41 pts (22.4%) | Avoidance of MAS, defined as any gut resection, stricturoplasty, or faecal diversion surgery during follow-up period—median (IQR) follow-up 68.7 (39.8–94.8) months. | Reduced need for MAS in patients demonstrating complete or partial MH compared to those not, 14.1% vs. 38.4% of patients, p < 0.0001 |

| Frøslie at al., 2007, retrospective observational cohort study [21] | 495 pts with newly diagnosed UC (354) or CD (141) with endoscopic assessment at baseline, 1 and 5 years | Definition of MH not stated. Present in 178 (50%) of UC patients and 53 (38%) of CD patients at one year. | Avoidance of colectomy at 5 years | Presence of MH at 1 year follow-up associated with significantly reduced risk of colectomy at 5 years, RR 0.22 (95% CI, 0.06–0.79; p = 0.02) |

| Long-term mucosal healing | ||||

| Shah et al., 2016, meta-analysis of 13 prospective studies [16] | 2073 pts with active UC | Multiple definitions among included studies | MH at ≥52 weeks post treatment commencement and ≥6 months post finding of MH | pOR of 8.40 (95% CI, 3.13–22.53; p < 0.00001) for achieving long-term MH in patients achieving MH vs. those not |

| Shah et al., 2016, meta-analysis of 12 prospective studies [17] | 673 pts with active CD | Multiple definitions among included studies | Long-term CR. Long-term defined as ≥50 weeks from study outset | pOR of 14.30 (95% CI, 5.57–36.74; p < 0.00001) for long-term MH in patients achieving MH vs. those not |

| Colombel et al., 2011, retrospective analysis of previous RCT’s [18] | 728 UC pts with MES ≥ 2, treated with IFX or placebo | MES | Sustained mucosal healing at both weeks 30 and 54 | Lower MES at week 8 associated with increased rate of sustained MH at both weeks 30 and 54, 77% MES 0, 54% MES 1, 21% MES 2, 6.7% MES 3, p < 0.0001 among IFX-treated patients |

| Af Björkesten et al., 2013, prospective observational study [22] | 42 pts with active CD treated with IFX or adalimumab | MH: SES-CD 0–2. MH present in 10 (24%) patients at 3 months post therapy commencement. | Presence of MH at 1 year | Patients with MH at 3 months more likely to demonstrate MH at 1 year than those without, 70% vs. 17%, p = 0.01 |

| Study, Year, Design | Population (No., UC/CD), Follow-Up | Presence of Baseline Endoscopic Activity (No., %) | No. of Endoscopic Assessments, No. (%) pts Undergoing | No. of Therapy Adjustments Made | Definition of MH, Definition of ER, No. (%) Achievement | Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bouguen et al., 2014, retrospective observational study [34] | 60 pts, 100% UC, median follow-up 76 weeks | 45 (75%) | 2: 26 (43%) 3: 26 (43%) 4: 8 (13%) Median interval between consecutive endoscopies 25 weeks (IQR, 16–42 weeks) | 51 adjustments made within the 45 pts with endoscopic disease activity | MH: MES = 0. MH: 27 (60%) pts with baseline endoscopic disease activity | MH associated with: Post-endoscopy adjustments in medical therapy made in the case of persistent endoscopic activity (HR 9.8, 95% CI 3.6–34.5; p < 0.0001). |

| Bouguen et al., 2014, retrospective observational study [35] | 67 pts, 100% CD, median follow-up 62 weeks | 67 (100%) | 2: 40 (60%) 3: 21 (31%) 4: 6 (9%) Median interval between consecutive endoscopies 24 weeks (IQR, 17–38 weeks) | 72 adjustments made as a result of endoscopic findings of ulceration | MH: absence of any ulcers in GIT. ER: downgrading of deep ulcers to superficial ulcers or the disappearance of superficial ulcers. MH: 34 (50.7%) pts, ER: 41 (61.1%) pts | MH associated with: <26 weeks between endoscopic procedures (HR 2.35; p= 0.035), adjustment to medical therapy when MH was not observed (HR 4.28; p = 0.0003). |

| Meade et al., 2023, retrospective observational study [36] | 50 pts, 100% CD | 50 (100%) | 2: 50 (100%) Interval between endoscopies not stated | 0 | MH: SES-CD ≤ 2 ER: >50% reduction in SES-CD MH: 25 (50%) ER: 35 (70%) | Treatment failure associated with: Failure to achieve MH (HR 11.62, 95% CI 3.33–40.56; p = 0.003), failure to achieve ER (HR 30.30, 95% CI 6.93–132.30; p < 0.0001). |

| Mao et al., 2017, retrospective observational study [37] | 272 pts, 100% CD Median follow-up 33 months (IQR 27–38 months). | 272 (100%) | 2: 272 (100%) 3: 154 (56.6%) 4: 69 (25.3%) 5: 26 (9.6%) 6: 10 (3.6%) 7: 4 (1.5%) Median interval between consecutive endoscopy 24 weeks (IQR: 17–38 weeks). | 237 adjustments made as a result of endoscopic findings of ulceration | MH: mucosal activity score of 0–2 MH: 126 (46.3%) endoscopic score system adopted from Af Björkesten et al. [38], mucosal activity scored from in most affected area. | MH associated with: <26 weeks between endoscopic procedures (HR 1.56; 95% CI 1.05–3.39; p = 0.03), adjustment of medical therapy when MH was not achieved (HR 2.07; 95% CI 1.26–2.33; p < 0.01), CRP normalisation within 12 weeks (HR 3.23; 95% CI 1.82–5.88; p < 0.01). |

| Wetwittayakhlang et al., 2022, prospective, observational study [39] | 104 pts, 82 (79%) CD, 22 (21%) UC, consecutively recruited | 70.6% CD 81.3% UC | 2 (relative proportions of study population not stated) | Not stated | MH: not stated MH at 6 months: 46.2% of CD pts with baseline endoscopic activity. 25% of UC pts with baseline activity MH at 12 months: 44.4% of CD pts with baseline endoscopic activity. 33% of UC pts with baseline activity | Not stated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

West, J.; Tan, K.; Devi, J.; Macrae, F.; Christensen, B.; Segal, J.P. Benefits and Challenges of Treat-to-Target in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6292. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196292

West J, Tan K, Devi J, Macrae F, Christensen B, Segal JP. Benefits and Challenges of Treat-to-Target in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(19):6292. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196292

Chicago/Turabian StyleWest, Jack, Katrina Tan, Jalpa Devi, Finlay Macrae, Britt Christensen, and Jonathan P. Segal. 2023. "Benefits and Challenges of Treat-to-Target in Inflammatory Bowel Disease" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 19: 6292. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196292

APA StyleWest, J., Tan, K., Devi, J., Macrae, F., Christensen, B., & Segal, J. P. (2023). Benefits and Challenges of Treat-to-Target in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(19), 6292. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196292