A Survey to Quantify the Number and Structure of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Retrieval Programs in the United States

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

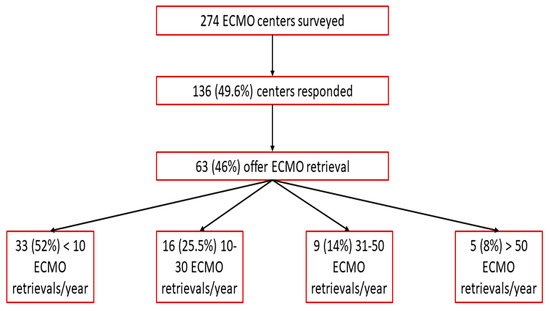

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guglin, M.; Zucker, M.J.; Bazan, V.M.; Bozkurt, B.; El Banayosy, A.; Estep, J.D.; Pinney, S.P. Venoarterial ECMO for Adults: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labib, A.; August, E.; Agerstrand, C.; Frenckner, B.; Laufenberg, D.; Lavandosky, G.; Fajardo, C.; Gluck, J.A.; Brodie, D. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Guideline for Transport and Retrieval of Adult and Pediatric Patients with ECMO Support. ASAIO J. 2022, 68, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peek, G.J.; Mugford, M.; Tiruvoipati, R.; Wilson, A.; Allen, E.; Thalanany, M.M.; Elbourne, D. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009, 374, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biscotti, M.; Agerstrand, C.; Abrams, D.; Ginsburg, M.; Sonett, J.; Mongero, L.; Takayama, H.; Brodie, D.; Bacchetta, M. One Hundred Transports on Extracorporeal Support to an Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Center. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 100, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonadonna, D.; Barac, Y.D.; Ranney, D.N.; Rackley, C.R.; Mumma, K.; Schroder, J.N.; Daneshmand, M.A. Interhospital ECMO Transport: Regional Focus. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 31, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryner, B.; Cooley, E.; Copenhaver, W.; Brierley, K.; Teman, N.; Landis, D.; Rycus, P.; Hemmila, M.; Napolitano, L.M.; Haft, J.; et al. Two decades’ experience with interfacility transport on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 98, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalia, A.A.; Axtel, A.; Villavicencio, M.; D’Allesandro, D.; Shelton, K.; Cudemus, G.; Ortoleva, J. A 266 Patient Experience of a Quaternary Care Referral Center for Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation with Assessment of Outcomes for Transferred Versus In-House Patients. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2019, 33, 3048–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, D.S.; Pranikoff, T.; Younger, J.G.; Swaniker, F.; Hemmila, M.R.; Remenapp, R.A.; Copenhaver, W.; Landis, D.; Hirschl, R.B.; Bartlett, R.H. A review of 100 patients transported on extracorporeal life support. ASAIO J. 2002, 48, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihu, M.R.; Maybauer, M.O.; Cain, K.; Swant, L.V.; Harper, M.D.; Schoaps, R.S.; Brewer, J.M.; Sharif, A.; Benson, C.; El Banayosy, A.M.; et al. Bridging the gap: Safety and outcomes of intensivist-led ECMO retrievals. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1239006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, K.E.; Duffett, M.; Kho, M.E.; Meade, M.O.; Adhikari, N.K.; Sinuff, T.; Cook, D.J.; for the ACCADEMY Group. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2008, 179, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbaro, R.P.; Odetola, F.O.; Kidwell, K.M.; Paden, M.L.; Bartlett, R.H.; Davis, M.M.; Annich, G.M. Association of hospital-level volume of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cases and mortality. analysis of the extracorporeal life support organization registry. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 191, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combes, A.; Brodie, D.; Bartlett, R.; Brochard, L.; Brower, R.; Conrad, S.; De Backer, D.; Fan, E.; Ferguson, N.; Fortenberry, J.; et al. Position paper for the organization of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation programs for acute respiratory failure in adult patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Diepen, S.; Katz, J.N.; Albert, N.M.; Henry, T.D.; Jacobs, A.K.; Kapur, N.K.; Kilic, A.; Menon, V.; Ohman, E.M.; Sweitzer, N.K.; et al. Contemporary Management of Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 136, e232–e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrell, A.J.C.; Pilcher, D.V.; Pellegrino, V.A.; Bernard, S.A. Retrieval of Adult Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation by an Intensive Care Physician Model. Artif. Organs 2018, 42, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Han, X.; Huang, R.; Yu, C.; Fang, M.; Yang, W.; Zha, Y.; Shao, M. Intensivist-Led Transportation of Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Single Center Experience. ASAIO J. 2023, 69, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraai, E.; Teixeira, J.P.; Patel, I.A.; Wray, T.C.; Mitchell, J.A.; George, N.; Kamm, A.; Henson, J.; Mirrhakimov, A.; Guliani, S.; et al. An Intensivist-Led Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Program: Design, Implementation, and Outcomes of the First Five Years. ASAIO J. 2022, 69, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, S.A.; Grier, L.R.; Scott, L.K.; Green, R.; Jordan, M. Percutaneous cannulation for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation by intensivists: A retrospective single-institution case series. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouch, M.; Green, A.; Damuth, E.; Noel, C.; Bartock, J.; Rosenbloom, M.; Schorr, C.D.; Rios, R.R.; Loperfido, N.B.; Puri, N. Rapid Development and Deployment of an Intensivist-Led Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Cannulation Program. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 50, e154–e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffatt-Bruce, S.; Crestanello, J.; Way, D.P.; Williams, T.E. Providing cardiothoracic services in 2035: Signs of trouble ahead. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Minnen, O.; Jolink, F.E.; van den Bergh, W.M.; Droogh, J.M.; Lansink-Hartgring, A.O.; Dutch ECLS Study Group. International Survey on Mechanical Ventilation During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2023; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mihu, M.R.; Swant, L.V.; Schoaps, R.S.; Johnson, C.; El Banayosy, A. A Survey to Quantify the Number and Structure of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Retrieval Programs in the United States. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061725

Mihu MR, Swant LV, Schoaps RS, Johnson C, El Banayosy A. A Survey to Quantify the Number and Structure of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Retrieval Programs in the United States. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(6):1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061725

Chicago/Turabian StyleMihu, Mircea R., Laura V. Swant, Robert S. Schoaps, Caroline Johnson, and Aly El Banayosy. 2024. "A Survey to Quantify the Number and Structure of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Retrieval Programs in the United States" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 6: 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061725

APA StyleMihu, M. R., Swant, L. V., Schoaps, R. S., Johnson, C., & El Banayosy, A. (2024). A Survey to Quantify the Number and Structure of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Retrieval Programs in the United States. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(6), 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061725