Comparison of Hemodynamic Factors Predicting Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Key Questions

1.1. What Is Already Known about This Subject?

1.2. What Does This Study Add?

1.3. How Might This Impact on Clinical Practice?

2. Introduction

3. Methods

3.1. Definitions

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Critical Appraisal

3.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

3.5. Five Different Analyses Were Made

- (1)

- Analysis of UV-variables. The number of studies in which the hemodynamic variable was indicated as a significant predictor, summed up per variable.

- (2)

- Main analysis of the number of studies in which the hemodynamic variable was a predictor of prognosis in MV-analysis. A UV-variable, whether non-significant or significant in UV-analysis, could only be included in the main analysis if an MV-analysis was present in the study. A summary analysis was made on quantitative information on prognostic strength of each variable in MV-analysis using hazard ratio (HR), odds ratio (OR) and relative risk (RR).

- (3)

- A subanalysis of the hemodynamic predictors in MV-analysis in the four selected HF-populations.

- (4)

- Influence of the study quality on the number of studies containing significant or non-significant MV hemodynamic variables of prognosis, by categorizing quality into low- and high-quality categories and by using the Fisher’s exact test. Quality was defined as the number of predefined critical appraisal shortcomings of the study.

- (5)

- An additional analysis was performed for comparison between one hemodynamic variable and hemodynamic or other variables in MV-analysis (methods in Supplement 5). Three particular predictors of prognosis were added in the comparison between MV-predictors because of their well-known prognostic significance: age, natriuretic peptide levels and VO2-max. Results were evaluated in terms of the number of comparisons in which a hemodynamic variable remained a prognostic predictor in MV-analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Critical Appraisal

4.2. Included Articles and Data Extraction

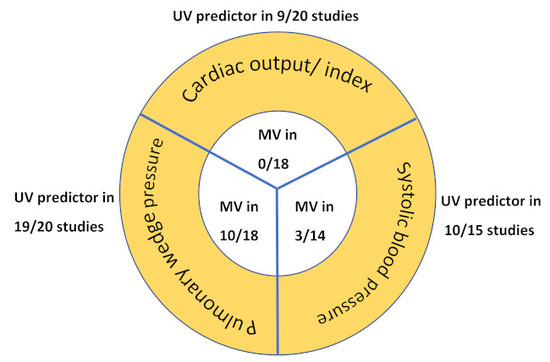

4.3. Univariate Analysis of Hemodynamic Predictors of Prognosis

4.4. Multivariate Analysis (Main Analysis)

4.5. Prognostic Value of Hemodynamic Factors within HF Populations

4.6. Influence of Study Quality Score

4.7. Comparison Between Hemodynamic Factors and Confounders in MV Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Cardiac Index: No Independent Predictor of Prognosis

5.2. Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure: Strongest Predictor of Prognosis

5.3. Systolic Blood Pressure

5.4. Population Differences

5.5. Hemodynamic Profiles

5.6. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHF | acutely decompensated heart failure |

| CHF | chronic heart failure |

| CI | cardiac index |

| CO | cardiac output |

| HF | heart failure |

| HTX | heart transplantation |

| LVAD | left ventricular assist device |

| MV | multivariate |

| UV | univariate |

| PCWP | pulmonary capillary wedge pressure |

| SBP | systolic blood pressure |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| RR | relative risk |

References

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.; Coats, A.J.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.P.; Jessup, M.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2129–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwald, E. Heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2013, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschöpe, C.; Sanderson, J.E.; Rusconi, C.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Rademakers, F.E.; Marino, P.; Smiseth, O.A.; de Keulenaer, G.; Borbély, A.; et al. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: A consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 2539–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, K.; Bennett, D.; Conrad, N.; Williams, T.M.; Basu, J.; Dwight, J.; Woodward, M.; Patel, A.; McMurray, J.; MacMahon, S. Risk prediction in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2014, 2, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouwerkerk, W.; Voors, A.A.; Zwinderman, A.H. Factors influencing the predictive power of models for predicting mortality and/or heart failure hospitalization inpatients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2014, 2, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceia, F.; Fonseca, C.; Mota, T.; Morais, H.; Matias, F.; de Sousa, A.; Oliveira, A.G.; EPICA Investigators. Prevalence of chronic heart failure in Southwestern Europe: The EPICA study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2002, 4, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, L.W.; Bellil, D.; Grover-Mckay, M.; Brunken, R.C.; Schwaiger, M.; Tillisch, J.H.; Schelbert, H.R. Effects of afterload reduction (diuretics and vasodilators) on left ventricular volume and mitral regurgitation in severe congestive heart failure secondary to ischemic or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1987, 60, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Moustgaard, R.; Wedel-Heinen, I. Cochrane Informatics and Knowledge Management Department: Covidence/1. 2015. Available online: http://tech.cochrane.org/our-work/cochrane-author-support-tool/covidence (accessed on 1 April 2018).

- Hayden, J.A.; Côté, P.; Bombardier, C. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J.A.; van der Windt, D.A.; Cartwright, J.L.; Côté, P.; Bombardier, C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, A.M.; Baron, D.W.; Hickie, J.B. Prognostic guides in patients with idiopathic or ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy assessed for cardiac transplantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 1990, 65, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.; Gullestad, L.; Vagelos, R.; Do, D.; Bellin, D.; Ross, H.; Fowler, M.B. Clinical, hemodynamic, and cardiopulmonary exercise test determinants of survival in patients referred for evaluation of heart failure. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998, 129, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, D.M.; Eisen, H.; Kussmaul, W.; Mull, R.; Edmonds, L.H.; Wilson, J.R. Value of peak exercise oxygen consumption for optimal timing of cardiac transplantation in ambulatory patients with heart failure. Circulation 1991, 83, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohria, A.; Tsang, S.W.; Fang, J.C.; Lewis, E.F.; Jarcho, J.A.; Mudge, G.H.; Stevenson, L.W. Clinical assessment identifies hemodynamic profiles that predict outcomes in patients admitted with heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, M.R.; Hasselblad, V.; Stinnett, S.S.; Gheorghiade, M.; Swedberg, K.; Califf, R.M.; O’Connor, C.M. Hemodynamic profiles of advanced heart failure: Association with clinical characteristics and long-term outcomes. J. Card. Fail. 2001, 7, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frea, S.; Pidello, S.; Canavosio, F.G.; Bovolo, V.; Botta, M.; Bergerone, S.; Gaita, F. Clinical assessment of hypoperfusion in acute heart failure. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.R.; Stinnett, S.S.; McNulty, S.E.; Gheorghiade, M.; Zannad, F.; Uretsky, B.; Adams, K.F.; Califf, R.M.; O’Connor, C.M. Hemodynamics as surrogate end points for survival in advanced heart failure: An analysis from FIRST. Am. Heart J. 2001, 141, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denardo, S.J.; Vock, D.M.; Schmalfuss, C.M.; Young, G.D.; Tcheng, T.E.; O’Connor, C.M. Baseline hemodynamics and response to contrast media during diagnostic cardiac catheterization predict adverse events in heart failure patients. Circ. Heart Fail. 2016, 9, e002529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchier, L.; Babuty, D.; Cosnay, P.; Autret, M.L.; Fauchier, J.P. Heart rate variability in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: Characteristics and prognostic value. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1997, 30, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciosa, J.A.; Wilen, M.; Ziesche, S.; Cohn, J.N. Survival in men with severe chronic left ventricular failure due to either coronary heart disease or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1983, 51, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, S.; Rovere MT, L.; Pinna, G.D.; Maestri, R.; Borroni, E.; Porta, A.; Mortara, A.; Malliani, A. Different spectral components of 24 h heart rate variability are related to different modes of death in chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita, M.; Arizón, J.M.; Bueno, G.; Latre, J.M.; Sancho, M.; Torres, F.; Giménez, D.; Concha, M.; Vallés, F. Clinical and hemodynamic predictors of survival in patients aged < 65 years with severe congestive heart failure secondary to ischemic or nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1993, 72, 413–417. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, D.B.; Lang, C.C.; Rayos, G.H.; Shyr, Y.; Yeoh, T.K.; Pierson, R.N., III; Davis, S.F.; Wilson, J.R. Hemodynamic exercise testing. A valuable tool in the selection of cardiac transplantation candidates. Circulation 1996, 94, 3176–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.S.; Henderson, G.; McDonagh, T.A. The prognostic use of right heart catheterization data in patients with advanced heart failure. How relevant are invasive procedures in the risk stratification of advanced heart failure in the era of neurohormones? J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2005, 24, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, S.; Gavazzi, A.; Campana, C.; Inserra, C.; Klersy, C.; Sebastiani, R.; Arbustini, E.; Recusani, F.; Tavazzi, L. Independent and additive prognostic value of right ventricular systolic function and pulmonary artery pressure in patients with chronic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grigioni, F.; Potena, L.; Galiè, N.; Fallani, F.; Bigliardi, M.; Coccolo, F.; Magnani, G.; Manes, A.; Barbieri, A.; Magelli, C.; et al. Prognostic implications of serial assessments of pulmonary hypertension in severe chronic heart failure. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2006, 25, 1241–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metra, M.; Faggiano, P.; D’Aloia, A.; Nodari, S.; Gualeni, A.; Raccagni, D.; dei Cas, L. Use of cardiopulmonary exercise testing with hemodynamic monitoring in the prognostic assessment of ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999, 33, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlekauff, H.R.; Stevenson, W.G.; Stevenson, L.W. Prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation in advanced heart failure. A study of 390 patients. Circulation 1991, 84, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, D.; Brozena, S.C. Assessing risk by hemodynamic profile in patients awaiting cardiac transplantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 1994, 73, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, A.; Horwich, T.B.; Fonarow, G.C. Comparison of usefulness of each of five predictors of mortality and urgent transplantation in patients with advanced heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 106, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieszczańska-Małek, M.; Zieliński, T.; Piotrowski, W.; Korewicki, J. Prognostic value of pulmonary hemodynamic parameters in cardiac transplant candidates. Cardiol. J. 2014, 21, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stevenson, L.W.; Tillisch, J.H.; Hamilton, M.; Luu, M.; Chelimsky-Fallick, C.; Moriguchi, J.; Kobashigawa, J.; Walden, J. Importance of hemodynamic response to therapy in predicting survival with ejection fraction ≤ 20% secondary to ischemic or nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1990, 66, 1348–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, D.; Eitan, A.; Dragu, R.; Burger, A.J. Relationship between reactive pulmonary hypertension and mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2011, 4, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J.N.; Levine, T.B.; Olivari, M.T.; Garberg, V.; Lura, D.; Francis, G.S.; Simon, A.B.; Rector, T. Plasma norepinephrine as a guide to prognosis in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984, 311, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.B.; Mentz, R.J.; Stevens, S.R.; Felker, G.M.; Lombardi, C.; Metra, M.; Stevenson, L.W.; O’Connor, C.M.; Milano, C.A.; Rogers, J.G.; et al. Hemodynamic predictors of heart failure morbidity and mortality: Fluid or flow? J. Card. Fail. 2016, 22, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfs, S.; Zeh, W.; Hochholzer, W.; Jander, N.; Kienzle, R.P.; Pieske, B.; Neumann, F.J. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure during exercise and long-term mortality in patients with suspected heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 3103–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goliasch, G.; Zotter-Tufaro, C.; Aschauer, S.; Duca, F.; Koell, B.; Kammerlander, A.A.; Ristl, R.; Lang, I.M.; Maurer, G.; Bonderman, D.; et al. Outcome in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: The role of myocardial structure and right ventricular performance. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concato, J.; Peduzzi, P.; Holford, T.R.; Feinstein, A.R. Importance of events per independent variable in proportional hazards analysis I. Background, goals, and general strategy. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1995, 48, 1495–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, C.B.; DeVore, A.D.; Felker, G.M.; Wojdyla, D.M.; Hernandez, A.F.; Milano, C.A.; O’Connor, C.M.; Rogers, J.G. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with heart failure and discordant findings by right-sided heart catheterization and cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 114, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methvin, A.; Georgiopoulou, V.V.; Kalogeropoulos, A.P.; Malik, A.; Anarado, P.; Chowdhury, M.; Hussain, I.; Book, W.M.; Laskar, S.R.; Smith, A.L.; et al. Usefulness of cardiac index and peak exercise oxygen consumption for determining priority for cardiac transplantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 105, 1353–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, C.E.; Whinnett, Z.I.; Davies, J.E. Quantifying the paradoxical effect of higher systolic blood pressure on mortality in chronic heart failure. Heart 2009, 95, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, I.S.; Rector, T.S.; Kuskowski, M.; Thomas, S.; Holwerda, N.J.; Cohn, J.N. Effect of baseline and changes in systolic blood pressure over time on the effectiveness of valsartan in the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial. Circ. Heart Fail. 2008, 1, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho-Gomes, A.C.; Rahimi, K. Management of blood pressure in heart failure. Heart 2019, 105, 589–595. [Google Scholar]

- Drazner, M.H.; Hellkamp, A.S.; Leier, C.V.; Shah, M.R.; Miller, L.W.; Russell, S.D.; Young, J.B.; Califf, R.M.; Nohria, A. Value of clinician assessment of hemodynamics in advanced heart failure: The ESCAPE trial. Circ. Heart Fail. 2008, 1, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Population. | Study Author + Year + Reference | Country | Baseline Year | Study Design | Patient nr | Mean Age (yrs) | Primary Outcome | Follow-Up Duration (months) | Number Events | CI Present (A), Present & Tested in UV (B), or Not Present (X) | PCWP Present (A), Present & Tested UV (B) or Not Present (X) | SBP Present (A), Present & Tested UV (B) or Not Present (X) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHF | Denardo et al. (2016) [19] | U.S.A. | 2008 | Prospective Cohort | 150 | 66 | mortality, HF hospitalization, rehospitali-zation | 12 | 39 (13 mortality, 26 HF hospitalization/rehospitalization) | B | B | B |

| Fauchier et al. (1997) [20] | France | 1983 | Prospective Cohort | 93 | 51.3 ± 11 | Mortality, HTX, cardiomyoplasty | 49.5 ± 35.6 | 23 (14 mortality, 8 HTX, 1 cardiomyoplasty) | B | B | B | |

| Franciosa et al. (1983) [21] | U.S.A. | 1981 | Retrospective Cohort study | 182 | 56.5 | Mortality | 12 ± 10 | 88 | B | B | B | |

| Guzzetti et al. (2005) [22] | Italy | 1991 | Prospective Cohort | 330 | 54 | progressive pump failure death + urgent HTX | Median 34 | 108 (62 progressive pump failure death, 17 urgent HTX, 29 sudden death) | B | B | B | |

| HTX | Anguita et al. (1993) [23] | Spain | 1986 | Prospective Cohort study | 130 | 45 ± 12 | mortality, HTX | 15 ± 11 | 93 (46 died, 47 HTX) | B | B | B |

| Chomsky et al. (1996) [24] | U.S.A. | 1993 | Prospective Cohort | 185 | 51 ± 11 | mortality and HTX was censored | 11 ± 6.9 | 32 died (and 36 HTX) | B | B | X | |

| Gardner et al. (2005) [25] | U.K. | 2002 | Prospective Cohort | 97 | 50.9 ± 10.5 | all-cause mortality or urgent HTX | 13.2 | 21 | B | B | X | |

| Ghio et al. (2001) [26] | Italy | 1992-1998 | Prospective Cohort | 377 | 51 ± 10 | Cardiac death or urgent HTX | 17.2 | 140 | B | B | X | |

| Grigioni et al. (2006) [27] | Italy | 1996 | Retrospective Cohort | 196 | 54 ± 9 | CV death and acute HF leading to urgent HTX | 24 ± 20 | 91 | B | B | B | |

| Metra et al. (1999) [28] | Italy | 1992 | Prospective Cohort | 219 | 55 ± 10 | Mortality & urgent HTX | 6 (6–54) | 38 (32 died and 6 urgent HTX) | B | B | B | |

| Middlekauff et al. (1991) [29] | U.S.A. | 1983 | Prospective & Retrospective Cohort study | 390 | 49 ± 12 | Total mortality and sudden death (pts undergoing HTX are withdrawn from analysis at the time of surgery) | 8.4 ± 10.8 | 98 (total mortality 98 of which 56 sudden deaths) (HTX = 105) | B | B | A | |

| Morley et al. (1994) [30] | U.S.A. | 1989 | Prospective Cohort | 138 | 52 ± 10 | Mortality | 12 | 50 | B | B | X | |

| Sachdeva et al. (2010) [31] | U.S.A. | 1999 | Retrospective Cohort | 1215 | 53 ± 13 | Mortality & urgent HTX | 24 (31 ± 32) | 442 (234 died, 208 urgent HTX) | B | B | B | |

| Sobieszczańska-Malek et al. (2014) [32] | Poland | 2003 | Prospective Cohort | 559 | 50.1 | Mortality/emergency HTX | 21,5 | 139 | B | B | B | |

| Stevenson et al. (1990) [33] | U.S.A. | 1985 | Prospective Cohort | 152 | 45 ± 13 | overall mortality (including urgent HTX), HTX | 12 | 84 (41 died + 6 urgent HTX, 37 HTX) | B | B | B | |

| ADHF | Aronson et al. (2011) [34] | U.S.A. | 1999 | Prospective RCT | 242 | 61 ± 14 | Mortality | 6 | 61 | B | B | B |

| Cohn et al. (1984) [35] | U.S.A. | 1984 | Prospective Cohort | 106 | 54.8 | Mortality | 1 to 62 | 60 | B | B | B | |

| Cooper et al. (2016) [36] | U.S.A. | 2000 | Prospective RCT | 151 | 59 | Mortality, cardiovascular hospitalization, HTX | 6 | 103 | B | B | B | |

| HFPEF | Dorfs et al. (2014) [37] | Germany | 1996 | Retrospective Cohort study | 355 | 61.2 ± 11.3 | All-cause mortality | 112 | 58 | B | B | B |

| Goliasch et al. (2015) [38] | Austria | 2010 | Prospective Cohort study | 142 | 71 | Hospitalization for heart failure and/or death for cardiac reason | 10 | 43 | B | B | B |

| Study Population | Study Author + Year +Reference | Adequate Number of Patients in HF-Population <200 or >200 <200 = −1 & >200 = 0) | Valid and Reliable Measurement of Prognostic Variable; CO Thermodilution or Fick (Thermodilution/Unknown = −1 & Fick = 0) | Outcome Measurement Valid and Reliable: Absence (−1) or Presence (0) of Adjudication Commision/Cheched Externally | Study Attrition (Follow-Up Done in 90% or > of Patient Population) (N = −1 & Y = 0) | Age (or Other Important Predictive Variable) in MV-Analysis (N = −1 & Y = 0) | At Least 2 Other UV Significant Variables for HF in UV-Analysis (N = −1 & Y = 0) | n Events? < 50 or > 50 (<50 = N = −1 & >50 = Y = 0) | Ratio: n Events/n Variables > 10 (N = −1 & Y = 0) | Total # of Weak Points on Critical Appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHF | Denardo et al. (2016) [19] | −1 | thermodilution = −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −6 |

| Fauchier et al. (1997) [20] | −1 | Unknown = −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −6 | |

| Franciosa et al. (1983) [21] | −1 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | −1 | −5 | |

| Guzzetti et al. (2005) [22] | 0 | unknown = −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −4 | |

| HTX | Anguita et al. (1993) [23] | −1 | unknown = −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −5 |

| Chomsky et al. (1996) [24] | −1 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −5 | |

| Gardner et al. (2005) [25] | −1 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −6 | |

| Ghio et al. (2001) [26] | 0 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −3 | |

| Grigioni et al. (2006) [27] | 0 | unknown = −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −3 | |

| Metra et al. (1999) [28] | 0 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −4 | |

| Middlekauff et al. (1991) [29] | 0 | unknown = −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −4 | |

| Morley (1994) [30] | −1 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | −6 | |

| Sachdeva et al. (2010) [31] | 0 | unknown = −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | |

| Sobieszczańska-Malek et al. (2014) [32] | 0 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −3 | |

| Stevenson et al. (1990) [33] | −1 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −5 | |

| ADHF | Aronson et al. (2011) [34] | 0 | unknown = −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −3 |

| Cohn et al. (1984) [35] | −1 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −4 | |

| Cooper et al. (2016) [36] | −1 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −4 | |

| HFPEF | Dorfs et al. (2014) [37] | 0 | Fick = 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −2 |

| Goliasch et al. (2015) [38] | −1 | thermodilution = −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −5 |

| Patient Group | CI Number of Studies | PCWP Number of Studies | SBP Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHF | 0/4 | 4/4 | 0/4 |

| HTX | 0/10 | 4/10 | 2/6 |

| ADHF | 0/2 | 0/2 | 1/2 |

| HFPEF | 0/2 | 2/2 | 0/2 |

| Total of 18 included MV-studies | 0/18 | 10/18 | 3/14 |

| Variable | Variable Measurement Details | Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CI | Qualitative analysis | ||

| Continuous | Not Significant | [21,25,27,30,33,37] | |

| CI ≤ 1.9 L/min/m2 | Not Significant | [22] | |

| PCWP | Qualitative analysis | ||

| Continuous, per 1 mmHg | Not Significant | [23,24,28,30] | |

| Significant | [19,20,21,25,29,33] | ||

| Quantitative analysis | |||

| Continuous, per 1 mmHg | Sign: HR range = 1.09–1.30 | [38,37] | |

| PCWP ≥ 12 mmHg | Sign: HR= 2.21 (CI (95%) = 1.14–4.17) | [37] | |

| PCWP ≥ 18 mmHg | Sign: RR= 2.0 (CI (95%) = 1.1–3.5) | [22] | |

| PCWP ≥ 21 mmHg | Sign: OR= 2.6 (CI (95%) = 1.1–3.0) | [31] | |

| SBP | Qualitative analysis | ||

| Continuous, increase per 1 mmHg | Not Significant | [21,27,28,32,37] | |

| Significant | [23] | ||

| SBP ≤ 110 mmHg | Not Significant | [22] | |

| Quantitative analysis | |||

| Continuous, per 10 mmHg decrease | Sign: HR = 1.3 (CI (95%) = 1.1–1.5) | [34] | |

| SBP < 118 mmHg | Sign: OR = 2.8 (CI (95%) = 1.1–7.1) | [31] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aalders, M.; Kok, W. Comparison of Hemodynamic Factors Predicting Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1757. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101757

Aalders M, Kok W. Comparison of Hemodynamic Factors Predicting Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(10):1757. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101757

Chicago/Turabian StyleAalders, Margot, and Wouter Kok. 2019. "Comparison of Hemodynamic Factors Predicting Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 10: 1757. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101757

APA StyleAalders, M., & Kok, W. (2019). Comparison of Hemodynamic Factors Predicting Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(10), 1757. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101757