Development of Advanced Textile Finishes Using Nano-Emulsions from Herbal Extracts for Organic Cotton Fabrics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Test Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methodology of Herbal Extraction

- Extraction of oil: Both the herbs (Moringa oleifera and Aegle marmelos) were washed thoroughly with the distilled water and dried in the oven at 105 °C for one hour to remove all the dirt and impurities.

- Steam Distillation: The dried herb of 10 gm of Moringa oleifera, 5 gm of curry leaves and 100 mL coconut oil have been boiled by heating these constituents using steam supplied from a steam generator. The heat applied determines how effectively the plant material structure breaks down and bursts and releases the aromatic components of essential oils. Thus, the steam distillation extraction technique increases the isolated essential oil yields and reduces wastewater produced during the extraction process.

- Solvent extraction: The mixture is further used for the extraction of oil through the solvent extraction technique. The solvent used for extraction is 99% pure ethanol. The dried herbs are kept in the thimble of the Soxhlet extractor, and ethanol solution has been added. The extracted solution has been collected in the collector. The collected oil is then filtered, and once the solvent is evaporated, leaving the oil in the pot as residue.

- The extract yield has been calculated by:

- v.

- Preparation of nano-emulsion

- vi.

- Application on fabric:

- (i)

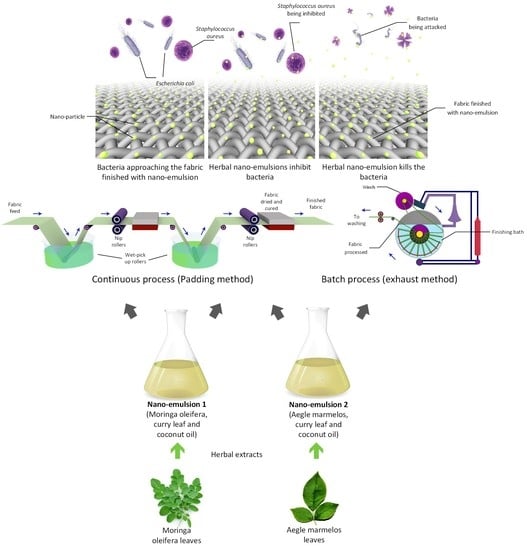

- Continuous process (Padding method): For organic cotton of both 20 and 60 g/m2 fabrics, sample size 21 cm × 30 cm was used. The fabric has been padded using a 2-dip and 2-nip method at 75% expression (the rate at which fabrics passes through) of the padding mangle. The padded fabric is then dried at 80 °C for five minutes and cured at 110 °C for three minutes. Padding has been carried out for all the five ratios of nano-emulsion for both herbal oils.

- (ii)

- Batch process (Exhaust method): The exhaust has been carried out using a Rota dryer machine. The fabric samples are kept in exhaustion at 1:50 LMR (liquid to material ratio) at 60 °C for one hour. The fabric after the exhaust method has been dried in air at room temperature. Exhaust has been carried out for all the five ratios of nano-emulsion for both the herbal oils.

2.3. Fabric Characterisation

2.4. Antimicrobial Tests

- A denotes the number of bacteria recovered from inoculated treated specimen after 24 h;

- B denotes the number of bacteria recovered from the inoculated treated specimen immediately after inoculation, i.e., 0 h.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Particle Size Analysis

3.2. pH Optimisation of Nano-Emulsions

3.3. Thermal Stability

3.4. Nano-Emulsion Percentage Add-on

3.5. Whiteness Index

3.6. Physical Properties

3.7. Antimicrobial Assessments

3.7.1. Quantitative Tests

3.7.2. Qualitative Tests

3.7.3. Antifungal Tests

3.8. ATR-FTIR Characterisation and SEM Analysis

3.9. Tensile Strength

3.10. Air Permeability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. GC-MS Analysis

Appendix A.1.1. Moringa oleifera

Appendix A.1.2. Aegle marmelos

Appendix A.1.3. Murraya koengii (Curry Leaf)

Appendix A.1.4. Coconut oil

Appendix B

| I | Breaking Extension (%) Moringa Oleifera | |||||||

| 20 gsm Padding | 60 gsm Padding | 20 gsm Exhaust | 60 gsm Exhaust | |||||

| Warp | Weft | Warp | Weft | Warp | Weft | Warp | Weft | |

| Control | 7.81 ± 0.00 | 27.33 ± 0.26 | 15.68 ± 0.14 | 14.675 ± 0.23 | 7.81 ± 0.00 | 27.325 ± 0.26 | 15.68 ± 0.14 | 14.68 ± 0.23 |

| 1:0.5 ratio | 8.03 ± 0.21 | 29.25 ± 0.16 | 16.31 ± 0.24 | 12.51 ± 0.00 | 7.19 ± 0.49 | 26.23 ± 1.86 | 18.51 ± 1.09 | 15.31 ± 0.18 |

| 1:1 ratio | 8.18 ± 0.00 | 26.34 ± 1.70 | 17.5 ± 0.97 | 12.49 ± 0.49 | 7.68 ± 0.09 | 27.71 ± 0.42 | 18.68 ± 0.52 | 11.71 ± 1.70 |

| 1:2 ratio | 29.18 ± 1.15 | 20.41 ± 0.54 | 15.01 ± 1.34 | 11.33 ± 0.85 | 8.57 ± 1.49 | 25.51 ± 5.28 | 18.00 ± 0.64 | 13.55 ± 1.27 |

| II | Breaking Extension (%) Aegle Marmelos | |||||||

| 20 gsm Padding | 60 gsm Padding | 20 gsm Exhaust | 60 gsm Exhaust | |||||

| Control | 7.81 ± 0.00 | 27.33 ± 0.26 | 15.68 ± 0.14 | 14.68 ± 0.23 | 7.81 ± 0.00 | 27.33 ± 0.26 | 15.68 ± 0.14 | 14.68 ± 0.23 |

| 1:0.5 ratio | 7.94 ± 0.00 | 20.82 ± 0.00 | 14.44 ± 0.00 | 13.02 ± 0.00 | 6.07 ± 0.72 | 23.70 ± 0.23 | 15.23 ± 0.25 | 14.33 ± 0.06 |

| 1:1 ratio | 6.62 ± 0.47 | 24.07 ± 0.72 | 17.78 ± 0.03 | 12.57 ± 0.26 | 8.08 ± 0.76 | 23.71 ± 0.69 | 15.44 ± 0.06 | 14.45 ± 0.11 |

| 1:2 ratio | 8.34 ± 0.00 | 21.83 ± 0.00 | 17.73 ± 0.00 | 13.22 ± 0.00 | 7.45 ± 0.26 | 27.80 ± 3.12 | 15.75 ± 0.07 | 14.11 ± 0.02 |

References

- Lim, S.; Hudson, S. Application of a fiber-reactive chitosan derivative to cotton fabric as an antimicrobial textile finish. Carbohydr. Polym. 2004, 56, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, A.; Maley, M.P. Survival of enterococci and staphylococci on hospital fabrics and plastics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 724–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, A.; Spencer, M.; Edmiston, C. Role of healthcare apparel and other healthcare textiles in the transmission of pathogens: A review of the literature. J. Hosp. Infect. 2015, 90, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, D.S.; Guedes, R.M.; Lopes, M.A. Antimicrobial approaches for textiles: From research to market. Materials 2016, 9, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, E.; Henriques, M.; Oliveira, R.; Dias, A.; Soares, G. 2010 Development of biofunctional textiles by the application of resveratrol to cotton, bamboo, and silk. Fibers Polym. 2016, 11, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Massella, D.; Argenziano, M.; Ferri, A.; Guan, J.; Giraud, S.; Cavalli, R.; Barresi, A.; Salaün, F. Bio-functional textiles: Combining pharmaceutical nanocarriers with fibrous materials for innovative dermatological therapies. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hipler, U.C.; Elsner, P. Biofunctional Textiles and the Skin. In Current Problems in Dermatology, 1st ed.; Itin, P., Jemec, G.B.E., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

- Carosio, F.; Cuttica, D.; di Blasio, A.; Alongi, J.; Malucelli, G. Layer by layer assembly of flame retardant thinfilms on closed cell PET foams: Efficiency of ammonium polyphosphate versus DNA. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 113, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, A.; Kumari, N.; Peila, R.; Barresi, A.A. Production of menthol-loaded nanoparticles by solvent displacement. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 95, 1690–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghayempour, S.; Montazer, M. Tragacanth Nanocapsules containing chamomile extract prepared through sono-assisted W/O/W microemulsion and UV cured on cotton fabric. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 170, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massella, D.; Ancona, A.; Garino, N.; Cauda, V.; Guan, J.; Salaun, F.; Barresi, A.A.; Ferri, A. Preparation of bio-functional textiles by surface functionalisation of cellulose fabrics with caffeine loaded nanoparticles. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 460, 012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massella, D.; Celasco, E.; Salaün, F.; Ferri, A.; Barresi, A. Overcoming the limits of flash nanoprecipitation: Effective loading of hydrophilic drug into polymeric nanoparticles with controlled structure. Polymers 2018, 10, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivero, P.; Urrutia, A.; Goicoechea, J.; Arregui, F. Nanomaterials for functional textiles and fibers. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, A.; Silvestre, A.; Freire, C.; Vilela, C. Modification of textiles for functional applications. In Fundamentals of Natural Fibres and Textiles; Textile Institute Book series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 303–365. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Cranston, R. Recent advances in antimicrobial treatments of textiles. Text. Res. J. 2008, 78, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ristić, T.; Zemljič, L.F.; Novak, M.; Kunčič, M.K. Antimicrobial efficiency of functionalised cellulose fibres as potential medical textiles. In Science against Microbial Pathogens: Communicating Current Research and Technological Advances; Méndez-Vilas, A., Ed.; Formatex Research Center: Badajoz, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Glazer, A.N.; Nikaido, H. Microbial Biotechnology: Fundamentals of Applied Microbiology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G. Antibacterial textile materials for medical applications. In Functional Textiles for Improved Performance, Protection and Health; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2011; pp. 360–375. [Google Scholar]

- Hegstad, K.; Langsrud, S.; Lunestad, B.; Scheie, A.; Sunde, M.; Yazdankhah, S. Does the wide use of quaternary ammonium compounds enhance the selection and spread of antimicrobial resistance and thus threaten our health? Microb. Drug Resist. 2010, 16, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Guggenbichler, P.; Heldt, P.; Jünger, M.; Ladwig, A.; Thierbach, H.; Weber, U.; Daeschlein, G. Hygienic relevance and risk assessment of antimicrobial-impregnated textiles. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2006, 33, 78–109. [Google Scholar]

- Windler, L.; Height, M.; Nowack, B. Comparative evaluation of antimicrobials for textile applications. Environ. Int. 2013, 53, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.-U.; Shahid, M.; Mohammad, F. Perspectives for natural product-based agents derived from industrial plants in textile applications—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 57, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Upadhyaya, I.; Kollanoor-Johny, A.; Venkitanarayanan, K. Combating pathogenic microorganisms using plant-derived antimicrobials: A minireview of the mechanistic basis. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 761741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Savoia, D. Plant-derived antimicrobial compounds: Alternatives to antibiotics. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheikh, J.; Bramhecha, I. Enzymes for green chemical processing of cotton. In The Impact and Prospects of Green Chemistry for Textile Technology; ul-Islam, S., Butola, B.S., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2019; pp. 135–160. [Google Scholar]

- Eid, B.; Ibrahim, N. Recent developments in sustainable finishing of cellulosic textiles employing biotechnology. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwar, R.; Joshi, M. Recent developments in antimicrobial finishing of textiles. AATCC Rev. 2004, 4, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, M.; Wazed, S.; Purwar, R.; Rajendran, S. Eco-friendly antimicrobial finishing of textiles using bioactive agents on natural products. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 2009, 34, 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Jain, A.; Panwar, S.; Gupta, D.; Kharea, S.K. Antibacterial activity of some natural dyes. Dyes Pigment 2005, 66, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A. Antimicrobial properties of tannins. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 3875–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastrad, J.V.; Goudar, G.; Byadgi, S.A. Characterisation of phenolic compounds in eucalyptus globulus and cymbopogan citratus leaf extracts. Bioscan 2016, 11, 2153–2156. [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal, P.; Preet, A.; Simran; Goel, G. Antimicrobial activity of herbal treated cotton fabric. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 4, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ijarotimi, O.; Adeoti, O.; Ariyo, O. Comparative study on nutrient composition, phytochemical, and functional characteristics of raw, germinated, and fermented moringa oleifera seed flour. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 1, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, L.; Doriya, K.; Kumar, D.S. Moringa oleifera: A review on nutritive importance and its medicinal application. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2016, 5, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viera, G.; Mourão, J.; Ângelo, Â.; Costa, R.; Vieira, R. Antibacterial effect (in vitro) of moringa oleifera and annona muricata against gram positive and gram-negative bacteria. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2010, 52, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rockwood, J.L.; Anderson, B.G.; Casamatta, D.A. Potential uses of moringa oleifera and an examination of antibiotic efficacy conferred by M oleiefera see and leaf extracts using crude extraction methods available to underserved indigenous population. Int. J. Phototherapy Res. 2013, 3, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Atef, N.; Shanab, S.; Negm, S.; Abbas, Y. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of some plant extracts against antibiotic susceptible and resistant bacterial strains causing wound infection. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maity, P.; Hansda, D.; Bandyopadhyay, U.; Mishra, D.K. Biological activities of crude extracts and chemical constituents of Bael, Aegle marmelos (L.) Corr. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2009, 47, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Katayama, T.; Nagai, I. Chemical significance of the volatile components of spices in the food preservative viewpoint-IV. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 1960, 26, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duke, J.A. Handbook of Biologically Active Phytochemicals and Their Activities; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pub Chem. National Library of Medicine. 2021. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- George, M.; Venkataraman, P.R.; Pandalai, K.M. Investigations on plant antibiotics, part II A search ofr antibiotic substance in some Indian medicinal plants. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 1947, 6B, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, C.G.; Magar, N.G. Antibiotic activity of some Indian medicinal plants. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 1952, 11B, 261. [Google Scholar]

- Pitre, S.; Srivastava, S.K. Pharmacological, microbiological and phytochemical studies on the root of Aegle marmelos. Fitoterapia 1987, 58, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.K.; Asthana, A.; Tripathi, N.N.; Dixit, S.N. Volatile plant products vis-à-vis potato pathogenic bacteria. Ind. Perf. 1981, 25, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, J.; Shurvell, H.; Lightner, D.; Cooks, R. Introduction to Organic Spectroscopy; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Wuelfing, W.; Kosuda, K.; Templeton, A.; Harman, A.; Mowery, M.; Reed, R. Polysorbate 80 UV/vis spectral and chromatographic characteristics—Defining boundary conditions for use of the surfactant in dissolution analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006, 41, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhongade, H.; Paikra, B.; Gidwani, B. Phytochemistry and pharmacology of moringa oleifera lam. J. Pharmacopunct. 2017, 20, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, K.; Ezhilarasu, A.; Gajendiran, K. Phytochemical screening, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of Aegle marmelos from Kolli Hills. Int. J. Interdiscip. Res. Rev. 2013, 1, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi, M.; Nateghi, L.; Rezaee, K. Investigation of physicochemical properties, fatty acids profile and sterol content in malaysian coconut and palm oil. Ann. Biol. Res. 2013, 4, 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- AATCC 100. Assessment of Antibacterial Finishes on Textile Materials: Developed by American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists; American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- AATCC 147. Antibacterial Activity Assessment of Textile Materials: Parallel Streak Method Developed by American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists; American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists: Research Triangle, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- AATCC 30-III. Assessment of Antifungal Activity on Textile Materials: Agar Plate Developed by American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists; American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists: Research Triangle, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM 5035-11. Standard Test Method for Breaking Force and Elongation of Textile Fabrics (Strip Method) ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) International; ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IS 15370. Indian Standard for Domestic Washing and Drying Procedure for Textile Testing; Standard identical to ISO 6330: New Delhi, India, 2000/2005. [Google Scholar]

- Korgaonkar, S.; Sayed, U. Nano herbal oils application on nonwovens. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 13, 1965–1970. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, R.; Radhai, R.; Kotresh, T.; Csiszar, E. Development of antimicrobial cotton fabrics using herb loaded nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 91, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aja, P.; Nwachukwu, N.; Ibiam, U.; Igwenyi, I.; Offor, C.; Orji, U. Chemical constituents of moringa oleifera leaves and seeds from Abakaliki, Nigeria. Am. J. Phytomed. Clin. Ther. 2014, 2, 310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Abidi, N.; Cabrales, L.; Haigler, C. Changes in the cell wall and cellulose content of developing cotton fibers investigated by FTIR spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 100, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innovation in Textiles. Antimicrobial Textiles Market to Reach $12.3 billion. 2019. Available online: https://www.innovationintextiles.com/antimicrobial-textiles-market-to-reach-123-billion/ (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Venkatraman, P.D.; Sayed, U.; Parte, S.; Korgaonkar, S. Consumer perception of environmentally friendly antimicrobial textiles: A case study from India. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. 2021, 10, 1782–1793. [Google Scholar]

- Muhuha, A.W.; Kang’ethe, S.K.; Kirira, P.G. Antimicrobial activity of moringa oleifera, aloe vera and warbugia ugandensis on multidrug resistant escherichia coli, pseudomonas aeruginosa and staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 4, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Dike-Ndudim, J.N.; Anyanwu, G.O.; Egbuobi, R.C.; Okorie, H.M.; Udujih, H.I.; Nwosu, D.C.; Okolie, N.J.C. Anti-bacterial and phytochemical potential of moringa oleifera leaf extracts on some wound and enteric pathogenic bacteria. Eur. J. Bot. Plant Sci. Phytol. 2016, 3, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dzotam, J.K.; Touani, F.K.; Kuete, V. Antibacterial and antibiotic-modifying activities of three food plants (Xanthosoma mafaffa Lam., Moringa oleifera (L.) schott and passiflora edulis sims) against multidrug-resistant (MDR) gram-negative bacteria. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caceres, A.; Cabrera, O.; Morales, O.; Mollinedo, P.; Mendia, P. Pharmacological properties of moringa oleifera: Preliminary screening for antimicrobial activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1991, 33, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Dama, G.; Surya Narayana, V.V.S.; Reddy, S. GC-MS analysis of the curry leaves (Murraya Koengii). Glob. J. Biol. Agric. Health Sci. 2014, 3, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gopala Krishna, A.G.; Raj, G.; Bhatnagar, A.S.; Prasanth Kumar, P.K.; Chandrashekar, P. Coconut oil: Chemistry, production and its applications—A review. Indian Coconut J. 2010, 73, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Moigradean, D.; Poiana, M.-A.; Alda, L.-M.; Gogoasa, I. Quantitative identification of fatty acids from walnut and coconut oils using GC-MS method. J. Agroaliment. Process. Technol. 2013, 19, 459–463. [Google Scholar]

- Dayrit, F. The properties of lauric acid and their significance in coconut oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 92, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales-Campos, H.; Reis de Souza, P.; Crema Peghini, B.; Santana da Silva, J.; Ribeiro Cardoso, C. An overview of the modulatory effects of oleic acid in health and disease. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Monolaurin. What is Monolaurin? 2021. Available online: https://www.healthline.com/health/monolaurin (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Nakatsuji, T.; Kao, M.; Fang, J.; Zouboulis, C.; Zhang, L.; Gallo, R.; Huang, C. Antimicrobial property of lauric acid against propionibacterium acnes: Its therapeutic potential for inflammatory acne vulgaris. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 2480–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Health Line. What is Lauric Acid? 2021. Available online: https://www.healthline.com/health/beauty-skin-care/what-is-lauric-acid#for-psoriasis (accessed on 12 July 2021).

| – | Fabric 1 | Fabric 2 | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fabric weight (g/m2) | 20 | 60 | GOTS † certified 100% Organic cotton fabric scoured and bleached white |

| Thickness (mm) | 0.2 | 0.5 | – |

| Fabric structure | Plain weave (1/1) | Twill weave (4/1) warp faced | 1.5 m width |

| Fabric count EPI × CPI | 75 × 27 | 117 × 38 | Ends per inch and picks per inch |

| Warp yarn count (tex) | 8 | 29 | – |

| Weft yarn count (tex) | 10 | 31 | – |

| Cover factor K = k1(warp) + k2(weft) | 21.2 + 64 | 63 + 21 | Area covered by a set of threads |

| Air permeability (cc/s) | >200 | 63 (±2.73) | The rate of airflow perpendicular through the fabric |

| Tensile strength (N) | Force required to break the fabric under tension | ||

| Warp | 322.39 (±11.01) | 662.09 (±2.71) | |

| Weft | 226.01 (± 1.29) | 287.84 (±12.76) | |

| Breaking extension (%) | Extension at peak force | ||

| Warp | 7.8 (±0) | 15.68 (±0.14) | |

| Weft | 27.53 (± 0.26) | 14.67 (±0.23) |

| Herbal Ratio | Test Culture | Reduction of Microorganisms (R) (%) Continuous Process (Padded) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moringa oleifera | Aegle marmelos | ||||

| 20 gsm | 60 gsm | 20 gsm | 60 gsm | ||

| 1:0.5 | S. aureus | 98.58 | 99.02 | 99.72 | 99.84 |

| E. coli | 98.46 | 99.03 | 99.70 | 99.82 | |

| 1:1 | S. aureus | 98.44 | 98.55 | 99.81 | 99.81 |

| E. coli | 98.13 | 98.38 | 99.78 | 99.80 | |

| 1:1 After 10 washes | S. aureus | 98.17 | 98.28 | 98.21 | 99.72 |

| E. coli | 97.79 | 98.14 | 98.09 | 99.66 | |

| 1:1 After 20 washes | S. aureus | 97.34 | 97.41 | 97.70 | 99.26 |

| E. coli | 96.86 | 97.16 | 97.58 | 99.03 | |

| 1:1.5 | S. aureus | 98.91 | 99.21 | 99.08 | 99.76 |

| E. coli | 98.84 | 99.15 | 99.16 | 99.72 | |

| 1:2 | S. aureus | 98.82 | 98.80 | 99.25 | 99.77 |

| E. coli | 98.53 | 98.86 | 99.24 | 99.74 | |

| 1:2.5 | S. aureus | 99.30 | 99.29 | 99.69 | 99.87 |

| E. coli | 99.05 | 99.07 | 99.70 | 99.76 | |

| Herbal Ratio | Test Culture | Reduction of Microorganism (R) %—Exhaust Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moringa Oleifera | Aegle Marmelos | ||||

| 20 gsm | 60 gsm | 20 gsm | 60 gsm | ||

| 1:1 | S. aureus | 98.76 | 99.21 | 99.04 | 99.74 |

| E. coli | 98.60 | 99.28 | 99.13 | 99.69 | |

| 1:1 After 10 washes | S. aureus | 98.39 | 99.09 | 98.67 | 99.18 |

| E. coli | 97.82 | 99.04 | 98.50 | 99.17 | |

| 1:1 After 20 washes | S. aureus | 97.62 | 98.26 | 98.28 | 98.52 |

| E. coli | 97.57 | 98.15 | 97.70 | 98.26 | |

| 1:2 | S. aureus | 99.43 | 99.12 | 99.27 | 99.78 |

| E. coli | 99.08 | 99.03 | 99.04 | 99.78 | |

| Sample Identification | Zone of Inhibition | Rating * | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Continuous Method) | |||||

| Moringa oleifera | Aegle marmelos | ||||

| Fabric | Ratio | ||||

| 20 gsm | 1:1 | No zone of inhibition | No zone of inhibition | 1 | No zone of inhibition could be seen around the fabric. There was a trace of fungal growth on the samples |

| 60 gsm | 1:1 | 42 mm | 45 mm | 0 | A zone of inhibition can be seen. Antifungal activity present |

| I | 20 gsm Padding | 60 gsm Padding | 20 gsm Exhaust | 60 gsm Exhaust | ||||

| Warp | Weft | Warp | Weft | Warp | Weft | Warp | Weft | |

| Control | 322.39 ± 11.01 | 226.01 ± 1.29 | 662.09 ± 2.71 | 287.84 ± 12.76 | 322.39 ± 11.02 | 226.01 ± 1.29 | 662.09 ± 2.71 | 287.84 ± 2.76 |

| 1:0.5 ratio | 317.61 ± 21.18 | 220.59 ± 2.77 | 609.42 ± 74.43 | 265.35 ± 15.85 | 274.92 ± 32.76 | 198.37 ± 7.25 | 604.91 ± 66 | 254.26 ± 2.68 |

| 1:1 ratio | 273.99 ± 0.25 | 217.25 ± 4.38 | 641.55 ± 20.65 | 266.18 ± 9.83 | 306.72 ± 15.90 | 224.2 ± 1.17 | 596.43 ± 37.29 | 231.01 ± 5.33 |

| 1:2 ratio | 202.64 ± 3.82 | 195.14 ± 7.41 | 572.09 ± 31.22 | 225.61 ± 5.23 | 239.73 ± 30.91 | 189.33 ± 32.22 | 548.09 ± 17.95 | 267.32 ± 2.96 |

| II | Tensile Strength (N) Aegle marmelos | |||||||

| 20 gsm Padding | 60 gsm Padding | 20 gsm Exhaust | 60 gsm Exhaust | |||||

| Control | 322.39 ± 11.02 | 226.01 ± 1.29 | 662.97 ± 2.71 | 287.85 ± 12.76 | 322.39 ± 11.02 | 226.92 ± 1.29 | 662.97 ± 2.71 | 287.85 ± 12.76 |

| 1:0.5 ratio | 306.43 ± 0 | 177.56 ± 0 | 629.93 ± 0 | 255.85 ± 0 | 249.42 ± 24.37 | 217.59 ± 23.33 | 609.62 ± 28.99 | 243.6 ± 19.03 |

| 1:1 ratio | 297.25 ± 10.15 | 211.51 ± 11.86 | 599.9 ± 21.34 | 248.65 ± 9.53 | 288.78 ± 8.75 | 206.66 ± 7.0 | 553.29 ± 11.47 | 243.8 ± 8.06 |

| 1:2 ratio | 313.23 ± 0 | 207.16 ± 0 | 626.39 ± 0 | 275.12 ± 0 | 280.57 ± 18.29 | 212.63 ± 8.89 | 529.54 ± 1.33 | 215.85 ± 6.58 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Venkatraman, P.D.; Sayed, U.; Parte, S.; Korgaonkar, S. Development of Advanced Textile Finishes Using Nano-Emulsions from Herbal Extracts for Organic Cotton Fabrics. Coatings 2021, 11, 939. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11080939

Venkatraman PD, Sayed U, Parte S, Korgaonkar S. Development of Advanced Textile Finishes Using Nano-Emulsions from Herbal Extracts for Organic Cotton Fabrics. Coatings. 2021; 11(8):939. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11080939

Chicago/Turabian StyleVenkatraman, Prabhuraj D., Usha Sayed, Sneha Parte, and Swati Korgaonkar. 2021. "Development of Advanced Textile Finishes Using Nano-Emulsions from Herbal Extracts for Organic Cotton Fabrics" Coatings 11, no. 8: 939. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11080939

APA StyleVenkatraman, P. D., Sayed, U., Parte, S., & Korgaonkar, S. (2021). Development of Advanced Textile Finishes Using Nano-Emulsions from Herbal Extracts for Organic Cotton Fabrics. Coatings, 11(8), 939. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11080939