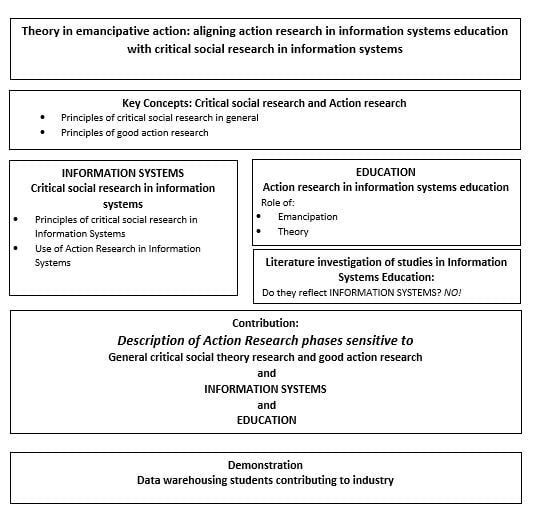

Theory in Emancipative Action: Aligning Action Research in Information Systems Education with Critical Social Research in Information Systems

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The target audience of AR in ISE studies can be extended to mainstream IS publications. We could not find publications in the past three years on the education of IS concepts in two of the most popular IS mainstream journals (Management Information Systems Quarterly (MISQ) and European Journal of Information Systems (EJIS)). If studies on ISE reflect the principles for conducting critical social theory research in IS [1], as published in the MISQ and promoted by the editor of EJIS (Rowe, 2012), there might be a higher acceptance rate of such studies. Our claim is supported by the publication of the AR project of Puhakainen and Siponen [4] in MISQ on an AR project on security training. This paper has a strong theoretical underpinning and the intervention is guided by theory;

- Researchers in IS who use AR may be drawn to extend their research to the education of their specific fields of interests if the guidelines for AR in IS are aligned with ISE research. Gibbs, et al. [5] have substantiated the growing trend in higher education institutions to “break[ing] down the demarcations between traditional scholarship, research and administration/organization”;

- The application of critical social theory assumptions has a strong history in AR in education (as we will indicate in the next section), and AR in IS will benefit from guidelines for critical social theory in AR in education;

- Intervention as part of AR in IS has a strong theoretical underpinning [6]. By adopting the same focus on theory when conducting AR in ISE, we have an opportunity to equip our students with a knowledge of these theories that they can then use as future IS practitioners.

2. Theoretical Perspectives on Critical Social Theory Research

2.1. Action Research in Critical Social Research

2.2. Action Research and Critical Social Theory in Information Systems

2.3. AR in Education from a Critical Social Theory Perspective: Emancipation and Theory

2.4. Review on the Use of AR in IS Education Literature

3. Action Research from a Critical Social Perspective

3.1. The FMA Model for Action Research

3.2. A CST Perspective on the Phases of AR

4. Illustrative Case Study

4.1. Background and Research Methodology

4.2. Guiding Literature

4.2.1. Critical Systems Heuristics

4.2.2. Project-Based Learning

4.3. Diagnosis Phase

4.4. Action Planning

4.5. Action Taking

4.6. Evaluating Success

4.7. Specifying Learning

5. Conclusions

- explicitly state the emancipative goals of their research to guide students to develop to their full potential;

- explicitly state a value position, in terms of what they believe is best for all involved and affected;

- explicitly reflect on their own assumptions and prevailing beliefs, i.e., their value position;

- use CST theories with a proven track record to guide emancipative change;

- make a contribution to CST;

- make a contribution to the scholarly fields of ISE and IS and AR; while

- benefitting their students and the larger community.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Myers, M.D.; Klein, H.K. A set of principles for conducting critical research in information systems. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, F. Toward a richer diversity of genres in information systems research: New categorization and guidelines. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2012, 21, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M. Qualitative Research in Information Systems. MIS Q. 1997, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhakainen, P.; Siponen, M. Improving employees’ compliance through information systems security training: An action research study. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 757–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, P.; Cartney, P.; Wilkinson, K.; Parkinson, J.; Cunningham, S.; James-Reynolds, C.; Zoubir, T.; Brown, V.; Barter, P.; Sumner, P.; et al. Literature review on the use of action research in higher education. Educ. Act. Res. 2017, 25, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskerville, R.L.; Wood-Harper, A.T. A Critical Perspective on Action Research as a Method for Information Systems Research. In Enacting Research Methods in Information Systems: Volume 2; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Theory and Practice. London: Heinemann; Heinemann: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- McNiff, J. Action Research: Principles and Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, W.; Kemmis, S. Becoming Critical: Knowing through Action Research; Deakin University: Victoria, Australia, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- McTaggart, R. Principles for Participatory Action Research. Adult Educ. Q. 1991, 41, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, L. Critical Social Research; Unwim Hyman: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, W.; Kemmis, S. Becoming Critical: Education Knowledge and Action Research; Taylor & Francis: Milton Park, Didcot, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Huang, H. What Is Good Action Research? Why the Resurgent Interest? Action Res. 2010, 8, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskerville, R.L. Investigating Information Systems with Action Research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 1999, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susman, G.I.; Evered, R.D. An Assessment of the Scientific Merits of Action Research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Frontiers in Group Dynamics: II. Channels of Group Life; Social Planning and Action Research. Hum. Relat. 1947, 1, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avison, D.; Lau, F.; Myers, M.; Nielsen, P.A. Action Research. Commun. ACM 1999, 42, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, F. Toward a Framework for Action Research in Information Systems Studies. Inf. Technol. People 1999, 12, 148–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, J.; Marshall, P. The Dual Imperatives of Action Research. Inf. Technol. People 2001, 14, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiasson, M.; Germonprez, M.; Mathiassen, L. Pluralist Action Research: A Review of the Information Systems Literature. Inf. Syst. J. 2009, 19, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Gallivan, M.J.; DeLuca, D. Furthering Information Systems Action Research: A Post-Positivist Synthesis of Four Dialectics. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2008, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgersson, S.; Melin, U. Pragmatic Dilemmas in Action Research: Doing Action Research with or without the Approval of Top Management? Syst. Pract. Act. Res. 2015, 28, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amber, Y.G. Using Ict for Social Good: Cultural Identity Restoration through Emancipatory Pedagogy. Inf. Syst. J. 2017, 28, 304–358. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, M.D.; Venable, J.R. A Set of Ethical Principles for Design Science Research in Information Systems. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlin, C.; Aybüke, A. Towards a Decision-Making Structure for Selecting a Research Design in Empirical Software Engineering. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2015, 20, 1427–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassey, M. Case Study Research in Educational Settings; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.P. A Short Guide to Action Research; Pearson/Allyn and Bacon Boston: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, G.E. Action Research: A Guide for the Teacher Researcher; Merrill Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Nixon, R. The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action Research; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Battiste, M. Decolonizing Education: Nourishing the Learning Spirit; Purich Publishing: Sascatoon, SK, Canada, 2013; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.C. Systems Thinking: Creative Holism for Managers; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zambo, D. Theory in the Service of Practice: Theories in Action Research Dissertations Written by Students in Education Doctorate Programs. Educ. Action Res. 2014, 22, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S. Critical Theory and Participatory Action Research. In The Sage Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice; Reason, P., Bradbury, H., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2008; pp. 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, W. Critical Heuristics of Social Planning: A New Approach to Practical Philosophy; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1983; Volume 5126. [Google Scholar]

- Kapenieks, J. Educational Action Research to Achieve the Essential Competencies of the Future. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2016, 18, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dewey, J. Education and Democracy; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Jakovljevic, M.; Ankiewicz, P. Project-Based Pedagogy for the Facilitation of Webpage Design. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2016, 26, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, L.; Hegarty, B.; Kelly, O.; Penman, M.; Coburn, D.; McDonald, J. Developing Digital Information Literacy in Higher Education: Obstacles and Supports. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2011, 10, 383–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hegarty, B.; Penman, M.; Brown, C.; Coburn, D.; Gower, B.; Kelly, O.; Sherson, G.; Suddaby, G.; Moore, M. Approaches and Implications of Elearning Adoption in Relation to Academic Staff Efficacy and Working Practice Final Report; Ministry of Education: Wellington, New Zealand, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Adesemowo, A.K.; Johannes, H.; Goldstone, S.; Terblanche, K. The Experience of Introducing Secure E-Assessment in a South African University First-Year Foundational Ict Networking Course. Afr. Educ. Rev. 2016, 13, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, T.D. Beyond the Yellow Brick Road: Mobile Web 2.0 Informing a New Institutional E-Learning Strategy. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuhadar, C.; Abdullah, K.U.Z.U. Improving Interaction through Blogs in a Constructivist Learning Environment. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2010, 11, 134–161. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, M.; Fonseca, B.; Morgado, L.; Martins, P. Improving Teaching and Learning of Computer Programming through the Use of the Second Life Virtual World. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 42, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaias, P.; Issa, T. Promoting Communication Skills for Information Systems Students in Australian and Portuguese Higher Education: Action Research Study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2014, 19, 841–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P.; Holwell, S. Information, Systems and Information Systems: Making Sense of the Field; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Churchman, C.W. The Systems Approach; Dell Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Network Theory Networks, Societies, Spheres: Reflections of an Actor-Network Theorist. Int. J. Commun. 2011, 5, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Basden, A. Philosophical Frameworks for Understanding Information Systems; IGI Global: Harrisburg, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dooyeweerd, H. Roots of Western Culture: Pagan, Secular, and Christian Options; Wedge at Foundation: Asheville, NC, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ackoff, R.L. Redesigning the Future: A Systems Approach to Societal Problems; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.W. A Review of Research on Project-Based Learning. Available online: http://www.bie.org/index.php/site/RE/pbl_research/29 (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- Helle, L.; Tynjälä, P.; Olkinuora, E. Project-Based Learning in Post-Secondary Education – Theory, Practice and Rubber Sling Shots. High. Educ. 2006, 51, 287–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code (ref) | Element | Description |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Abstraction | Through abstraction, the critical social researcher can reflect on the deeper problem situation to reveal underlying structures that are otherwise taken for granted. |

| H2 | Totality | Totality refers to the view that social phenomena are interrelated to form a whole. |

| H3 | Essence | Essence refers to the fundamental element of the analytical process. |

| H4 | Praxis | Praxis refers to practical reflective activity to relieve oppression. Learning takes place through action and reflection. Action is guided by existing theory. |

| H5 | Ideology | The worldview or Weltanschauung of the participants or alternatively, the inherent thought processes that guide specific (oppressive) actions. |

| H6 | Structure | The interrelatedness of elements in the problem situations. |

| H7 | History | “History refers both to the reconstructed account of the past events and the process by which the reconstruction is made” [11]. |

| H8 | Deconstruction and reconstruction | The critical researcher aims to deconstruct the situation into abstract concepts to study the interrelations between the concepts with the purpose of discovering the key to the structure of the situation. The core concept is used to reconstruct the situation. |

| Code (ref) | Criteria | Discussion Quoted from Bradbury-Huang [13] |

|---|---|---|

| BH1 | Articulation of objectives | The extent to which authors explicitly address the objectives they believe relevant to their work and the choices they have made in meeting those. |

| BH2 | Partnership and participation | The extent to and means through which the project reflects or enacts participative values and concern for the relational component of research. |

| BH3 | Contribution to action research theory/practice | The extent to which the project builds on (creates explicit links with) or contributes to a wider body of practice knowledge and/or theory that contributes to the action research literature. |

| BH4 | Methods and process | The extent to which the action research methods and process are articulated and clarified. |

| BH5 | Actionability | The extent to which the project provides new ideas that guide action in response to need. |

| BH6 | Reflexivity | The extent to which the authors explicitly locate themselves as change agents. |

| BH7 | Significance | The extent to which the insights in the manuscript are significant in content and process. By significant, we mean having meaning and relevance beyond their immediate context in support of the flourishing of persons, communities, and the wider ecology. |

| Code (ref) | Principle | Summary of Meaning Quoted from Myers and Klein [1] |

|---|---|---|

| Element: Critique | ||

| MK1 | The principle of using core concepts from critical social theorists. | Research methods must be guided by the work of scholars in the field of CST, such as Habermas. |

| MK2 | The principle of taking a value position. | Researchers must articulate their value position, such as equality or democracy. |

| MK3 | The principle of revealing and challenging prevailing beliefs and social practices. | The work of CST scholars can be used to highlight shortcomings of current thinking. |

| Element: Transformation | ||

| MK4 | The principle of individual emancipation. | Intervention should guide self-reflection and self-transformation to fulfil individual potential. |

| MK5 | The principle of improvements in society. | Transformation of more than the individual is possible and therefore the society may be improved. |

| MK6 | The principle of improvements in social theories. | Application of theory may lead to the improvement of these theories. |

| Paper | Goal | Theoretical Framework | Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kapenieks [37] | To improve selected competencies that students will need in the future in information systems (IS) students. | Dewey [38] is stated as the framework, but intervention is not explicitly linked to his critical aspects. | Three learning cycles: identification; construction of living theory; communication. |

| Jakovljevic and Ankiewicz [39] | To develop the webpage design skills of students. | Constructivist learning theory, various educational models. | Baskerville [14], depicted in Figure 1. |

| Jeffrey, et al. [40] | To identify obstacles to and support for fostering the development of the digital information literacy (DIL) of staff and students in higher education. | Three-step reflective framework of [41]. | Setting goals, searching for possible solutions, critical evaluation, determining new action. |

| Adesemowo, et al. [42] | To introduce secure e-assessment in ICT modules on networking. | Blooms taxonomy, constructivism, connectivism. | Participatory AR framework. |

| Cochrane [43] | To extend the use of mobile and Web 2.0 technology in an education institution’s approach to e-learning. | Social constructivist pedagogies. | Pre-trail, intervention, post-trial. |

| Cuhadar and Kuzu [44] | To improve interaction through blogs in an IT course. | Constructivism. | 🗴 |

| Esteves, et al. [45] | To present a framework for teaching and learning computer programming within the second life virtual framework. | 🗴 | Planning, acting, observing, reflecting. |

| Isaias and Issa [46] | To examine the value of the communication skills learning process through various assessments. | 🗴 | 🗴 |

| Transformation | Insight | Critique | Using Core Concepts from Critical Social Theorists (MK1) | Taking a Value Position (MK2) | Revealing and Challenging Prevailing Beliefs and Social Practices (MK3) | Individual Emancipation (MK4) | Improvements in Society (MK5) | Improvements in Social Theories (MK6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kapenieks [37] | Enhancing essential competencies of information systems (IS) students. | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 |

| Jakovljevic and Ankiewicz [39] | Improving the web design skills of students. | ✓ | 🗴 | 🗴 | 🗴 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 |

| Jeffrey, et al. [40] | Empowering participants. Reducing obstacles. New approaches to learning and personal growth in digital information literacy (DIL). | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 |

| Cochrane [43] | Developing the international community of practice model for supporting new technology integration, development, and change. | ✓ | 🗴 | 🗴 | 🗴 | 🗴 | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 |

| Adesemowo, et al. [42] | Introduction of secure e-assessment in ICT modules on networking. | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 | ✓ | 🗴 | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 |

| Cuhadar and Kuzu [44] | Improving instruction and social interaction. | ✓ | 🗴 | 🗴 | 🗴 | 🗴 | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 |

| Esteves, et al. [45] | Improving effectiveness in the learning of programming. | ✓ | 🗴 | 🗴 | 🗴 | 🗴 | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 |

| Isaias and Issa [46] | Promoting communication skills and boosting self-esteem. | ✓ | 🗴 | 🗴 | 🗴 | 🗴 | ✓ | ✓ | 🗴 |

| Description of AR Phases from a Critical Social Perspective Sensitive to Indicated Theoretical Frameworks. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Diagnosis | |||

| The aim of the diagnosis phase is to better understand the problem situation. From a CST perspective, this is the most important phase of the process. It is during this stage that the problem situation is deconstructed to identify oppressing structures. Care should be taken to understand the history and historical context of the situation. During diagnosis, the essence of the situation must be disclosed in the wider context of the problem environment and stakeholders. Churchman [48], another scholar in the critical tradition, argues that a holistic view (such as his systems approach) should identify the real objective of the situation, i.e., the objective that will not be sacrificed when priorities are set. This also relates to the ‘essence’. Reflection is part of diagnosis, which ties to abstraction to identify oppressing structures and worldviews present. Critical systems heuristics, developed by Ulrich [35], can be used to facilitate the process of abstraction and reflection, as shown in Section 4. | |||

| Applicable Principles from Theory | |||

| FMA Framework of Checkland and Holwell [47]: Refer to Figure 2 | Element Hi of Harvey [11]: Refer to Table 1 | Principle MKi of Myers and Klein [1]: Refer to Table 2 | Criterion BHi of Bradbury-Huang [13]: Refer to Table 3 |

| F: Framework for understanding; A: Specific problem area learning about (reflection). | H1: Abstraction H6: Structure; H7: Historical context; H3: Essence; H2: Totality; H5: Ideology; H8: Deconstruction. | MK1: Critical social theorists; MK3: Prevailing beliefs. | BH1: Objectives; BH2: Participants. |

| Phase 2: Action Planning | |||

| After the problem is understood and the oppressive structures have been identified, the CST action researcher finds appropriate and theoretical sound strategies to apply to the situation to facilitate the emancipation. Clear objectives for the intervention should be stated. In the CSH of Ulrich [35], the idea is to emancipate those affected by using strategies that are proven. He refers to the idea of a ‘guarantor’—some proof that the expert has reason to believe that the proposed intervention will be successful in relieving the oppressive structures identified in the previous phase. Key to action planning in CST is to understand that methods are based on certain assumptions. The CST researcher should take responsibility to understand these assumptions and evaluate the applicability of the proposed methods in the problem environment. The context of the problem situation should be taken into account, as promoted by Baskerville [14]. Focus should be on participative change rather than consultation. The participants should also take ownership of the action plan, rather than only the researcher. According to Ulrich [35], the power relation must be in favor of those ‘affected’ and not the ‘experts’. The result of the action planning phase should be an action plan that clearly indicates how the interests of the oppressed will be served by the proposed action and a substantiation that the proposed intervention is likely to succeed. | |||

| Applicable Principles from Theory | |||

| FMA Framework of Checkland and Holwell [47]: Refer to Figure 2 | Element Hi of Harvey [11]: Refer to Table 1 | Principle MKi of Myers and Klein [1]: Refer to Table 2 | Criterion BHi of Bradbury-Huang [13]: Refer to Table 3 |

| ‘M’ is the intervention that is applied to the problem ‘A’. The intervention should be informed by ‘F’ in such a way that reflection on its application assists reflection on ‘M’, but also on ‘F’ and ‘A’. Various social theories have been used to guide action in IS, including actor-network theory [49] and structuration theory [50] in IS. Basden [51] shows how the work of Dooyeweerd [52] is useful to guide action in IS. | H4: Praxis; H2: Totality. | MK1: Critical social theorists: Ulrich [35]; MK6: Improvements in social theories; Various social theories have been used to guide action in IS, including actor-network theory [49] and structuration theory [50] in IS. Basden [51] shows how the work of Dooyeweerd [52] is useful to guide action in IS. | BH1: Objectives; BH4: Methods and processes; BH7: Significance; BH5: Actionability; BH6: Reflexivity; BH2: Participants. |

| Phase 3: Action Taking | |||

| In this phase, the plan is executed. It is in this phase where individual emancipation and eventually improvement of society are achieved. Ulrich [35] focuses the attention on ‘witnesses’ of the affected, i.e., representatives of the oppressed in the process of intervention. Baskerville‘s [14] idea of participative change in the context of the client may facilitate this as long as it is done from a critical perspective, which has the interests of the oppressed in mind. In terms if our stance on emancipation, the goal of action taking in ISE is to ensure that students develop to their full potential. | |||

| Applicable Principles from Theory | |||

| FMA Framework of Checkland and Holwell [47]: Refer to Figure 2 | Element Hi of Harvey [11]: Refer to Table 1 | Principle MKi of Myers and Klein [1]: Refer to Table 2 | Criterion BHi of Bradbury-Huang [13]: Refer to Table 3 |

| Performing ‘M’ in ‘A’. | H4: Praxis; H8: Reconstruction. | MK4: Individual emancipation; MK5: Improvements to society. | BH5: Actionability; BH2: Participants. |

| Phase 4: Evaluation of Success | |||

| The aim of this phase is to evaluate the success of the intervention. From a CST perspective, this evaluation has a strong pragmatic character as the main measure of success is the individual (or group emancipation required, as identified during the diagnosis phase). Data collection and analysis methods of other paradigms are often used to demonstrate or understand the effects of the intervention. A CST researcher will take care to analyse the totality of the situation to ensure that unintended consequences are identified and that they do not create new oppressive structures. This is a longer-term view than is typical of most research projects. Once again, we urge the CST researcher to investigate the assumptions inherent to specific research methods to ensure validity and integrity. | |||

| Applicable Principles from Theory | |||

| FMA Framework of Checkland and Holwell [47]: Refer to Figure 2 | Element Hi of Harvey [11]: Refer to Table 1 | Principle MKi of Myers and Klein [1]: Refer to Table 2 | Criterion BHi of Bradbury-Huang [13]: Refer to Table 3 |

| Mostly in ‘A’. | H7: Historical; H2: Totality; H8: Reconstruction. | MK4: Individual emancipation; MK5: Improvements to society. | BH7: Significance (long term); BH4: Methods and processes. |

| Phase 5: Specifying Learning | |||

| In both the model of Baskerville (1999) and the FMA model, AR wants to achieve more than only individual emancipation. It is in this phase where the difference between consultation and AR is most evident. The consultant moves on to a new ‘A’, while the AR researcher tries to formulate abstractions or generalization of the experience to benefit the society and the scholarly society. The role of the researcher must be also reflected upon. | |||

| Applicable Principles from Theory | |||

| FMA Framework of Checkland and Holwell [47]: Refer to Figure 2 | Element Hi of Harvey [11]: Refer to Table 1 | Principle MKi of Myers and Klein [1]: Refer to Table 2 | Criterion BHi of Bradbury-Huang [13]: Refer to Table 3 |

| The CST researcher reflects not only on the emancipation in ‘A’, but also on his/her intervention ‘M’ and the ‘F’ framework of ideas used to plan the intervention. | H1: Abstraction. | MK4: Individual emancipation; MK5: Improvements to society; MK6: Improvements in social theories. | BH7: Significance (long term); BH6: Reflexivity. |

| Question | Student | University | Industry |

|---|---|---|---|

| What ought to be the purpose of the system (S); i.e., what goal stated ought S be able to achieve to serve the client? | To enlighten learners about what is done with the data after it has been collected, because the data warehousing (DW) module expands on the knowledge of databases. | To prepare students to contribute to industry and successfully design DW and to work in groups, to self-direct, and to become a life-long learner. | To teach future project managers how to report on the business or enterprise in its entirety. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goede, R.; Taylor, E. Theory in Emancipative Action: Aligning Action Research in Information Systems Education with Critical Social Research in Information Systems. Systems 2019, 7, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems7030036

Goede R, Taylor E. Theory in Emancipative Action: Aligning Action Research in Information Systems Education with Critical Social Research in Information Systems. Systems. 2019; 7(3):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems7030036

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoede, Roelien, and Estelle Taylor. 2019. "Theory in Emancipative Action: Aligning Action Research in Information Systems Education with Critical Social Research in Information Systems" Systems 7, no. 3: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems7030036

APA StyleGoede, R., & Taylor, E. (2019). Theory in Emancipative Action: Aligning Action Research in Information Systems Education with Critical Social Research in Information Systems. Systems, 7(3), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems7030036