1. Introduction

The relationship between crime and income inequality is complex and controversial. While there is some consensus that a relationship exists, the nature of it is the subject of much debate, which is further intensified by its relevance to the public debate [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In this paper, this relation is investigated in the context of urban geography: Does income inequality explain the geography of crime within cities?

This question has been relatively overlooked, and a satisfying answer is still absent. Traditionally, the theoretical base for a relationship between income inequality and crime has been given by theories such as strain theory [

6], relative deprivation theory [

7] and the economic theory of crime [

8,

9]; however, none of these theories explicitly address the spatial aspect. Conversely, income inequality is not prominently featured in any of the notable spatial theories of crime such as routine activities theory [

10] and crime pattern theory [

11,

12]. While a potential connection between income inequality and the spatial distribution of crime within a city could be conjectured by combining these different theories, this has not often been tested. Most empirical studies comparing crime rates and income inequality have been conducted at more macro-scales such as comparing cities, counties, or even whole regions or countries [

1,

3,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]; contrasting with that, I found only five studies analyzing this relationship at a within-city scale [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

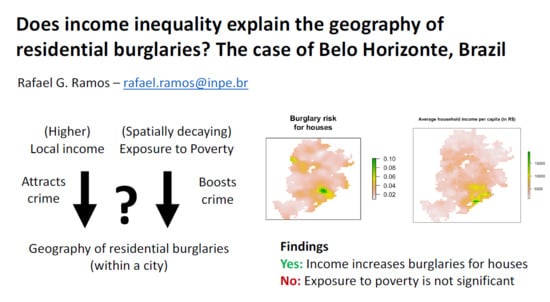

This research proposes a model to test whether and how income and its unequal distribution can explain the geography of residential burglaries within a city, while taking other factors potentially relevant to crime into account. More specifically, the questions aimed to be answered by the model are the following three:

What is the effect of local average income level on local burglary risk?

What is the effect of higher exposure to poverty on burglaries, when the local average income level is controlled?

What is the scale at which this exposure is most relevant?

In other words, this research aims to answer questions such as: Do higher income locations feature higher burglary risk? Given a higher income location, will the presence of nearby surrounding poverty increase the risk of burglary at that higher income location? What is meant by nearby, and at what scale is the effect of proximity to poverty relevant, if any?

The model was tested for residential burglaries in the city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. For the case tested in this paper, a strong positive correlation was found between burglary risk at houses and local average income, with the model explaining 61% of the variance. Exposure to poverty was found to be insignificant in independently influencing burglary risk at single family houses, regardless of the scale considered. For the risk of burglary at apartments, on the other hand, no significant effect was found for either local average income or exposure to poverty.

Burglary was chosen for this study since, as a type of property crime, it potentially has a more straightforward connection to income and related matters. Furthermore, since the targets of burglary are both explicit in space and unmoving (i.e., the residences are fixed in location), examining the spatial distribution is a less ambiguous task.

The study area for this research was the city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, the third largest city of the country in terms of metropolitan population. For the purposes of studying the relationship between crime and income inequality, Brazil is an important case, since it not only the ranks among the highest in violent crime [

25], it also ranks among the highest in income inequality [

26].

Within Brazil, Belo Horizonte is an adequate choice of city. Crime is more concentrated in Brazil’s largest cities, such as Belo Horizonte—Brazil’s third largest metropolitan area. Moreover, despite originally being a planned city, Belo Horizonte’s urban structure better matches that of other larger Brazilian cities in marked contrast to Rio de Janeiro and its unique landscape, the formal urban design of Brasília, or the sheer magnitude of São Paulo. That, combined with the fact that Belo Horizonte’s demographic profile closely matches the national average, should facilitate future comparisons to other cities in Brazil.

This article is organized as follows. The remainder of this section discusses the key theories and studies related to the topic of crime, income inequality and their geographies, which were used as the theoretical base for the model proposed here.

Section 2 (Material and Methods) describes the model proposed, as well as the data used in this study.

Section 3 (Results) summarizes the main results obtained, with

Section 4 (Discussion) providing an interpretation of these results, a comparison between this study and previous ones (including methodological aspects), and a summary of the main conclusions.

Theoretical Background and Literature Review

The theoretical base for a connection between income inequality and crime has been explored by different theoretical lines. In strain theory [

6] (and the similar relative deprivation theory [

7]), the presence of social inequalities (income inequality included) results in higher feelings and perceptions of injustice in society, leading to psychological strain that culminate in crime. Within this framework, the poor, confronted with what is perceived as the unattainable success standards of the middle-class, more likely suffer from psychological strain and resort to crime as an alternative route to success. The economic theory of crime [

8,

9], on the other hand, states that income inequality boosts crime because it increases the number of economically strained individuals who are be more pressured to resort to crime as a money-earning option while also sustaining a number of wealthy individuals who are adequate targets of property theft. Contrasting with the emotion-drive explanation of the strain and relative deprivation theories, the connection between crime and income inequality is instead economical, assuming rational decision making. The final general effect, though, is similar. However, while these theories offer plausible explanations for a connection between crime and income inequality, how this is manifested in space has not been directly analyzed.

Theories that do provide an explanation for spatial patterns crime, on the other hand, usually do not feature income-related aspects as prominent factors, and the specific connection between income inequality and the geography of crime is again not clear in these theories. Routine activities theory [

10] is one of the more prominent spatial theories of crime. As remarked by routine activities theory, in order for a crime to happen, three elements must converge in time and space: The presence of both a motivated offender and a suitable target, as well as the absence of a capable guardian. Based on this premise, routine activities theory then analyzes crime as a function of how these three different elements may vary in time and across space. Burglaries, for instance, are more common during the day because residences are more often vacant during this time, leading to increased opportunities for burglaries. Income is included in this framework as a modulator of opportunities and potential gains, with the theory explaining how times of economic boon could feature an increase in property crime rates: Increased wealth and income not only increase the consumption and acquisition of goods such as expensive electronics (increase in values targets) but also increase how often people go out at night for leisure activities (leaving not only their residences vacant but also increasing their own exposure to crime).

Crime pattern theory [

11,

12] further refined the approach from routine activities theory, presenting a more explicit spatial framework to explain crime in terms of flows of offenders, targets and guardians. According to crime pattern theory (and following routine activities theory), spatial patterns of crime are a product of the combined activities spaces of offenders, targets and guardians—an activity space being the collection of places and regions most frequently visited by an individual based on their daily routine. Activities spaces, on the other hand, are mostly defined and constrained by a few key nodes and connecting edges, such as a person’s home location, work-place, and preferred leisure venues (as well as the routes connecting these places). Therefore, spatial patterns of crime can be understood by analyzing these key nodes, an approach that has been used by the police to identify the likely home location of serial offenders.

Other important criminological theories can also be cited as relevant to the topic of crime, income inequality, and their geographies (even if these connections are not totally fleshed out). Rational choice theory [

27] models offender behavior as multi-level rational decision-making processes in which considerations of proximity and accessibility play a role in target selection. The income level of the target can be considered relevant within this framework, determining potential gain and thus influencing the target selection process. More indirectly, income and socioeconomic status can be considered as determining an offender’s background and social connections, factors which are at least partially contemplated in the theory. However, a straightforward, explicit model relating income and income inequality to the spatial distribution of crime has not been provided. Finally, social disorganization theory [

28] (and related theories such as collective efficacy [

29]) should be listed as an important theory that features both income and spatial aspects to a limited extent. The spatial variation of crime is explained as a function of neighborhood characteristics, with more socially disorganized neighborhoods featuring more crime. Social disorganization, on the other hand, is be caused by factors such as poverty, high residential turn-over and ethnic heterogeneity, all of which hinder the formation of social bonds within the neighborhood, leading to said disorganization and then crime. It is worth noting, then, a conflict between social disorganization theory and others such as rational choice theory regarding the role of income. While the first predicts that crime is concentrated in poor areas, the second predicts the opposite. This conflict can be solved, at least in part, by noting that different types of crime feature not only different spatial patterns but may also have different relationships to income and related aspects, some being related to wealth and others to poverty. Moreover, the type of connection may differ: Poverty (of the potential offender) is in many theories regarded as a motivator or strain factor, while wealth (of the potential target) is regarded as an attractor. This is related also to the problem of confounding areas of high crime occurrence with areas with high concentration of offenders living there, two sets that may not coincide. Finally, how far from one’s own neighborhood an offender is likely to go to commit a crime may vary.

While these theories tend to approach crime in a more general sense, there are few a priori reasons to expect that a burglary would not fit the outlined theoretical frameworks. The economic driver related to income inequality theories of crime appears particularly fit for property crimes such as burglary, in which one of the practical outcome is a forced “transfer of income.” Other crime theories described (e.g., routine activities, rational choice) show no obvious incompatibility with burglary, with this type of crime indeed being explicitly mentioned in some of these studies [

7,

8,

9,

10,

27]. The question, however, is whether these theories that suggest a plausible link between localized income inequality and burglary are indeed reflected in the empirical geography of burglaries within cities.

Few studies found by me have so far investigated the relationship between income inequality and the spatial distribution of crime within cities. Most empirical studies that have tested the relationship between crime and income inequality have done so using macro-units of analysis such as whole cities, counties, regions or countries. Not only have these studies often disagreed regarding the nature of this relationship, few have investigated this potential connection at the within-city scale—that is, whether income inequality can explain the specific spatial patterns of crime observed within a city. Only five studies could be found that have done such an analysis [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Of these, only one analyzed the effect on property crimes, with the others focusing solely on violent crimes. Different types of crime often display distinct dynamics, that particularly being the case when comparing property crimes such as burglary with violent crimes like homicide. As such, only the study of Hipp, 2007 [

21] can be considered to provide empirical evidence of the relationship between income inequality and the geography of burglaries within a city. In that study, the relationship between property crime (burglary and auto-theft) and income inequality was weak (albeit positive), contrasting with the stronger positive association detected between income inequality and violent crime. This again highlights the importance of more empirical studies to test potential relationships between income inequality and the geography of crime within cities.

To summarize, this subsection shows that a unified, explicit, and straightforward model relating income inequality to the spatial distribution of crime at a within-city scale is still lacking, but that multiple theories have offered elements that allow us to infer a potential relationship. In general, income has been theorized to have a dual effect: First, as a motivation (or strain) factor that presses the poorer to more likely consider crime as a money earning option; second, as an attractor, determining where opportunities for property crime are concentrated. Inequality should thus increase both of these aspects. Finally, the interaction between these two elements should be modulated by space, with interaction being more likely at smaller distances. Moreover, the perception of unattainable economic success described by strain theory can be theorized to be greater in a situation where the poorer and the richer are spatially closer. Therefore, according to this implied model, wealthier places are at greater risk than poorer ones, but, given two different wealthy locations, one closer to a poorer neighborhood is at greater risk. This theory has seldom been tested and fully formalized, in particular for within-city scales, and it is the objective of this study to contribute towards this goal. A proposed model is formally described in

Section 2, with the results of it being applied to residential burglaries in Belo Horizonte being shown in

Section 3.

Section 4 concludes with a summary of these results and a comparison of the methodology employed (and associated results) to previous studies.

3. Results

The estimated coefficients for average household income and exposure to poverty, varying with bandwidth size, as well as their corresponding

p-values, are shown in

Figure 6 for the case of single family houses.

Figure 7 shows how much the model fitness varied according to the bandwidth used: The graph on the left-hand side shows the R-squared value for the regression using different bandwidths, while the graph on the right shows the normalized values of three different fitness scores—R-squared, F-score, and Akaike information criterion—varying with the bandwidth.

As can be seen from

Figure 6, no statistically significant influence from exposure to poverty was found on burglary risk for houses at any of the bandwidths tested. Average household income, on the other hand, showed a high statistical significance, with higher income being associated with higher burglary risks. On average, a 10% increase in wealth is associated with a 5% increase in burglary risk for houses (using standardized units). As seen on

Figure 7, the regressed model showed greater least-squares fitness at two different local peaks, one for a bandwidth of 1000 m and one for a bandwidth of 8000 m. Alternative fitness metrics used (F-score and Akaike information criterion) showed a similar pattern. Nevertheless, R-squared values were very similar across bandwidths, and since exposure to poverty was observed to be not significant at any bandwidth, these differences of fitness can also be considered insignificant.

Finally,

Table 5 shows the coefficient for all variables used estimated using a bandwidth equal to 8000 m, which yielded the highest fitness overall.

The same study was then repeated for burglary risk for apartments.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the variation of fitness, coefficient value and

p-values at the various tested bandwidths.

In the case of burglary risk for apartments, neither average household income nor exposure to poverty were observed to influence risk in a statistically significant sense. In general, fitness tended to increase with the bandwidth; however, since the statistical power remained too weak, this bandwidth effect can be also considered insignificant. The regression coefficients and their statistical significance are shown in

Table 6.

Finally, based on these results, the answers to the specific questions investigated by this research (for the case of residential burglaries in Belo Horizonte) are the following:

1: What is the effect of local average income level to local burglary risks?

Average household income is positively related with burglary risk for houses. On average, a 10% increase in household income is related to a 5% increase in burglary risk for houses, using standardized units. However, average household income shows no statistically significant relationship with burglary risk for apartments.

2: What is the effect of higher exposure to poverty on burglaries when local average income level is controlled?

A higher exposure to poverty has no statistically significant effect on burglary risk for either houses or apartments.

3: What is the scale at which this exposure is most relevant?

The scale of exposure is irrelevant, since exposure at any scale was not observed to be significant, both for houses or apartments.

4. Discussion

The tested model succeeded in explaining approximately half of the variance in the observed distribution of burglary risk for houses. The observed distribution of burglaries in Belo Horizonte appears to be significantly related to income, with the risk of burglaries for houses being higher in areas with an higher average household income. For the case of apartments, however, a link was not found, and the variance explained by the model was small. Nevertheless, although the positive link between burglary risk and income exists only for houses and not for apartments, burglaries of houses correspond to the majority of cases in Belo Horizonte, both in absolute counts and in a relative (per residence) sense, highlighting the importance of these findings.

No evidence was found that exposure between different income groups increases burglary risk (either for houses or apartments). If local income level was fixed, increasing the local exposure of that area to poverty showed no significant effect on burglary risk. This was true for different spatial scales of exposure. In other words, the burglary risk for a wealthy house is indifferent to whether there are poor neighborhoods nearby or not, at least in this study. While in a limited sense, income inequality could be said to be connected to crime in that risk is different for different income groups, that is not usually the sense implied when a connection between inequality and crime is referred to.

These results by themselves do not necessarily disprove the theories that connect crime to inequality in a general sense. However, they do show that there is no obvious observable connection between burglary risk and exposure among different income groups for the case of Belo Horizonte. Rather, if burglary tends to be more likely in higher income areas but the presence of nearby poorer neighborhoods is irrelevant, that could plausibly be explained in terms of the distribution of opportunities: More income meaning more objects of value to be stolen. This theoretical explanation would also be consistent with houses being more at risk than apartments, since in Belo Horizonte (as in other Brazilian cities in general), residential apartments are generally considered safer because they more often feature security mechanisms such as doormen and security cameras. Another plausible factor that may explain this observed irrelevance of localized income inequality on burglary risk would be burglars (hypothetically) having a high mobility, not being limited to nearby wealthy locations or even avoiding them to avoid suspicion. Additionally, a different possibility would be that burglars do not come from the poorest backgrounds but have a different socioeconomic profile, and so the proximity to very poor neighborhoods becomes insignificant to burglary risk. Additional research on the social profile and modus-operandi of burglars in Brazil could aid in clarifying these possibilities.

In addition, no significant relationship was detected between burglary risk and any of the control variables, either for houses or apartments. These results again give weight to the explanation that the potential gain for burglars is the prime factor governing the spatial distribution of burglary risk. Variables that are plausible proxies to pedestrian flow and urban accessibility, such as the number of bus-stops, betweenness-centrality, commercial presence, and land-use density yielded no significant correlation—a connection that would, however, be expected under the framework of routine activities theory. Similarly, the proportion of rented residences yielded no correlation to risk, and income yielded a positive correlation to risk, both conflicting with what would be expected from an explanation based on social disorganization theory.

Whether these results can be generalized to other cities, however, would require repeating the study in different study areas. Compared to the results of Hipp, 2007 [

21], these results differ significantly. It is worth noting, however, that the methodologies differ significantly as well: In the study by Hipp, 2007 [

21], burglaries were not separated according to type of residence, the methods used for estimating burglary risk differed, and finer units of analysis were employed in this study. This is not a demerit of Hipp, 2007, since that study was not specifically tailored for analyzing burglary and income inequality, being focused on other questions (ethnic heterogeneity and multiple types of crimes), but it does justify why a different methodology was chosen in this study. Lastly, another important difference concerns the specific metric chosen for measuring income inequality. Contrasting to that of Hipp, 2007 and other studies [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] in which an income inequality metric such as the Gini index was used, this study modelled the effect of income inequality by having a (spatially lagged) exposure to poverty variable act as an interactive variable which boosted the effect of local household income (another independent variable in the model). This design was chosen in order to explicitly model the inequality effect described in most theories (e.g., economy of crime, relative deprivation and strain theories), with wealth acting as an attractor to crime and poverty acting (at distance) as a booster to such crime rates. Using an inequality metric such as the Gini index, on the other hand, can generate results that are harder to interpret within the context of this research. Due to income distribution being often more concentrated at the upper end, the income gap between the poor and the middle class is smaller (at least in numeric terms) than the gap between the middle class and the rich. As such, areas mixing middle-class and upper-class households tend to feature a higher inequality index (e.g., Gini index) than areas mixing middle-class and poor households. While this type of inequality could be hypothesized to be relevant, it is nevertheless different from the usual sense of inequality most often present in criminological theories in which poverty is a significant component. Having mean income as an independent variable can aid in controlling for this correlation between income inequality and wealth, but the difficulty remains of discerning whether inequality is more related to poverty or to wealth. The same reasoning (ease of interpretation and avoiding confounding results) applies to other model design choices such as the choice of not using segregation metrics like those proposed by Reardon and O’Sullivan, 2004 [

40] or Feitosa et al., 2007 [

41].

A potential limitation of this study is the presence of underreporting in crime rates and whether there are any biases associated with it—a common challenge with many crime studies. Burglary data used in this work came from the police records of reported cases; however, not all the cases are necessarily reported to the police, with the reporting rate for burglaries in Belo Horizonte having been estimated as 33% [

36]. Since the main interest of this study was in the spatial distribution of crime and the factors explaining it, the main concern was not so much about the absolute numbers of crime rates but whether there are any biases on their spatial distribution and whether these biases are related to any of the explanatory factors considered in the analysis. For instance, could the positive relationship observed between burglary risk for houses and income be a product of wealthier citizens reporting more often? One possible way to determine the presence of such biases is conducting a victimization survey; unfortunately, however, I have found no such survey for the specific case of residential burglaries in Belo Horizonte (or in Brazil as a whole). A victimization survey [

42] conducted for other types of crime in Brazil did provide some information, showing that there is both a higher reporting rate from wealthier citizens and a higher victimization rate for property crimes such as theft and robbery. As such, if burglaries in Belo Horizonte do follow the same pattern observed for other property crimes in Brazil as a whole, then this positive relationship between burglary risk and income could be a genuine one, albeit one boosted by the different reporting rates. However, a more specific victimization survey focused on burglaries in Belo Horizonte (or at least in Brazil) would be required to better gauge the potential biases from underreporting.

Finally, there is the question on whether the connection between income, poverty and inequality to crime as modelled and tested in this paper is justifiable. For instance, issues such as the penalization of poverty [

43,

44] raise a cautionary note not only on the potential analytical biases of linking poverty to crime but also on the more practical and ethical ramifications of considering such a hypothetical link. On the other hand, there is a range of theories that give some support to that assumption (as described in the introduction). This study attempts to be neutral on that respect, testing a hypothetical link that is recurrent outside of academia (justifiably or not) and that is supported or suggested by current criminological theory. The outcome of this study is that this hypothetical link was not observed, which, while not sufficient to disprove a link between crime and inequality in a more general and absolute sense, is an indicator that such relationship is more nuanced, perhaps less spatially explicit, and possibly more dependent on the type of crime considered.

In summary, this paper has proposed a quantitative model to evaluate the relationship between income inequality and the geography of crime within cities. The model implements a combination of mechanisms described or suggested by theories relating crime to income inequality, with local wealth acting as an attractor to crime and surrounding poverty acting as a boosting factor. The model was applied to residential burglaries in the city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. The study has shown that mean local household income is significant and positively correlated to increased burglary risk for houses, explaining 61% of the variance; the presence of nearby poverty is irrelevant. These results and others suggest that the observed geography of residential burglaries is shaped by the distribution of opportunities and potential gains for burglars, and this geography is not a product of localized income disparity. This type of study has seldom been done at a within-city scale, in particular for property crimes.