Implications of Winter NAO Flavors on Present and Future European Climate

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- Which are the NAO flavors in the in the present and future simulations of the ECHAM5 model?

- -

- Do these flavors change at the end of the 21st century?

- -

- What are the implications of the NAO flavors on temperature and precipitation over Europe according to the same model?

- -

- Are these implications significantly different from the typical response to NAO?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Self-Organizing Maps

2.2.2. Defining the NAO Flavors

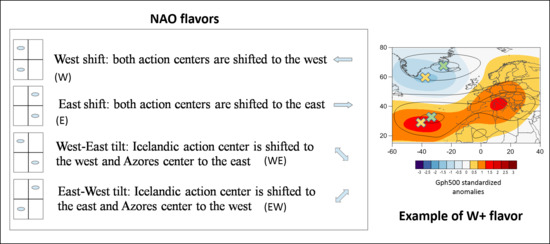

- West shift (W): both action centers are shifted to the west of the NAO prototype centers.

- West-east tilt (WE): the Icelandic center is shifted to the west and the Azores one to the east.

- East shift (E): both action centers are shifted to the east

- East-west tilt (EW): the NAO pattern is tilted, the Icelandic center is shifted to the east and the Azores one to the west.

3. Results

3.1. NAO Flavors

3.2. NAO Flavors and Temperature over Europe

3.3. NAO Flavors and Precipitation over Europe

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- NAO is not a stationary pattern. Its centers of action exhibit different spatial variations, affecting temperature and precipitation regimes in Europe in different ways. This is why the definition of NAO flavors is a useful approach. It is important to mention that the NAO flavors should be defined from scratch each time for different datasets and time-periods. The ones presented here regard the winter field of geopotential height at 500hPa for 1971–2000 and 2071–2100 in the ECHAM5 model. Most of the NAO flavors found in these simulations do not change significantly in frequency and persistence at the end of the 21st century. However, they do have significant implications for temperature and precipitation over Europe, that differ from the typical NAO effects, when all NAO+ or NAO− days are taken under consideration.

- The model identifies the centers of NAO for the present period to the west of those in the reanalysis data, while the centers for the future period present a significant displacement to the east (mainly compared to the model present period, but also to the reanalysis). This is in agreement with several studies documenting eastward shifts of the NAO centers of action, in both observed data [61] and in experiments with general circulation models of different levels of complexity [9,62,63]. According to Peterson et al. [64], it is the strength of the mean westerly flow that drives the changes in the spatial structure of interannual NAO variability in a nonlinear way. In agreement with the above statements, we find that the most frequent NAO flavor is an east shift, for both positive and negative NAO.

- The typical warmer winter temperatures over Europe are mainly found to be occurring during the E+ flavor. Yao & Luo [60] also reached similar conclusions, as an NAO pattern with its northern center of action located to the east of 10° W of longitude has a wider and stronger imprint on European temperature than when it is located in a westerly position. Colder winter temperatures are found over northern Europe, mostly as a response to the W− flavor, while this is the case for Eastern Europe when WE− is dominant.

- Precipitation is spatially more incoherent compared to temperature and this is reflected in our results. During the W+ and EW+ flavors, precipitation amounts are significantly lower in western Europe, while this is the case for Scandinavia when W− and WE− flavors are dominant. Significantly more precipitation is occurring over northeastern Europe mainly with W+, and with E- over southwestern Europe. For more detailed and localized effects of the NAO flavors on regional precipitation, one should look at the different SOMs that comprise those flavors, instead of only looking at their composites, as this way, regional differences even out.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hurrell, J.W. Decadal trends in the North Atlantic Oscillation: Regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 1995, 269, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wibig, J. Precipitation in Europe in relation to circulation patterns at the 500 hPa level. Int. J. Climatol. 1999, 19, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaife, A.A.; Folland, C.K.; Alexander, L.V.; Moberg, A.; Knight, J.R. European climate extremes and the North Atlantic Oscillation. J. Clim. 2008, 21, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaife, A.A.; Knight, J.R.; Vallis, G.K.; Folland, C.K. A stratospheric influence on the winter NAO and North Atlantic surface climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hurrell, J.W.; Kushnir, Y.; Ottersen, G.; Visbeck, M. An overview of the North Atlantic Oscillation. Geophys. Monogr. Am. Geophys. Union 2003, 134, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Ting, M.; Kushner, P.J. A robust empirical seasonal prediction of winter NAO and surface climate. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogers, J.C. The Association between the North Atlantic Oscillation and the Southern Oscillation in the Northern Hemisphere. Mon. Weather Rev. 1984, 112, 1999–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmer, M.; Jung, T. Evidence for a recent change in the link between the North Atlantic Oscillation and Arctic Sea ice export. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2000, 27, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulbrich, U.; Christoph, M. A shift of the NAO and increasing storm track activity over Europe due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas forcing. Clim. Dyn. 1999, 15, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousi, Ε.; Anagnostopoulou, C.; Tolika, K.; Maheras, P. Representing teleconnection patterns over Europe: A comparison of SOM and PCA methods. Atmos. Res. 2015, 152, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousi, E.; Ulbrich, U.; Rust, H.W.; Anagnostolpoulou, C. An NAO climatology in reanalysis data with the use of self-organizing maps. In Perspectives on Atmospheric Sciences; Karacostas, T., Bais, A., Nastos, P.T., Eds.; Springer Atmospheric Sciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 719–724. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D.; Gong, T. A possible mechanism for the eastward shift of interannual NAO action centers in last three decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattiaux, J.; Vautard, R.; Cassou, C.; Yiou, P.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Codron, F. Winter 2010 in Europe: A cold extreme in a warming climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, D.; Chen, X.; Feldstein, S.B. Linear and nonlinear dynamics of North Atlantic Oscillations: A new thinking of symmetry breaking. J. Atmos. Sci. 2018, 75, 1955–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, S.; Baxter, S. Teleconnections. In Encyclopedia of Atmospheric Sciences, 2nd ed.; North, G., Ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 90–109. [Google Scholar]

- Roeckner, E. IPCC MPI-ECHAM5_T63L31 MPI-OM_GR1. 5L40 20C3M_All Run No. 3: Atmosphere 6 HOUR Values MPImet/MaD Germany; World Data Center for Climate: Hamburg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Roeckner, E.; Lautenschlager, M.; Schneider, H. IPCC-AR4 MPIECHAM5_T63L31 MPI-OM_GR1.5 L40 SRESA1B Run No.3: Atmosphere 6 HOUR Values MPImet/MaD Germany; World Data Center for Climate: Hamburg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stoner, A.M.K.; Hayhoe, K.; Wuebbles, D.J. Assessing general circulation model simulations of atmospheric teleconnection patterns. J. Clim. 2009, 22, 4348–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeckner, E.; Bäuml, G.; Bonaventura, L.; Brokopf, R.; Esch, M.; Giorgetta, M.; Hagemann, S.; Kirchner, I.; Kornblueh, L.; Manzini, E.; et al. The Atmospheric General Circulation Model EHAMPart I: Model Description; MPI für Meteorologie: Hamburg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jungclaus, J.H.; Keenlyside, N.; Botzet, M.; Haak, H.; Luo, J.J.; Latif, M.; Marotzke, J.; Mikolajewicz, U.; Roeckner, E. Ocean circulation and tropical variability in the coupled model ECHAM5/MPI-OM. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 3952–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohonen, T. Self-organized formation of topologically correct feature maps. Biol. Cybern. 1982, 43, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. Self-Organizing Maps; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miljković, D. Brief review of self-organizing maps. In Proceedings of the 2017 40th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 22–26 May 2017; pp. 1061–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos, T. Large-scale circulation anomalies conducive to extreme precipitation events and derivation of daily rainfall in Northeastern Mexico and Southeastern Texas. J. Clim. 1999, 12, 1506–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitson, B.; Crane, R. Self-organizing maps: Applications to synoptic climatology. Clim. Res. 2002, 22, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusch, D.B.; Alley, R.B.; Hewitson, B.C. North Atlantic climate variability from a self-organizing map perspective. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuenemann, K.C.; Cassano, J.J.; Finnis, J. Synoptic forcing of precipitation over Greenland: Climatology for 1961–1999. J. Hydrometeorol. 2009, 10, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousi, E.; Mimis, A.; Stamou, M.; Anagnostopoulou, C. Classification of circulation types over Eastern mediterranean using a self-organizing map approach. J. Maps 2014, 10, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reusch, D.B.; Alley, R.B.; Hewitson, B.C. Relative performance of self-organizing maps and principle component analysis in pattern extraction from synthetic climatological data. Polar Geogr. 2005, 29, 188–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiang, M.Y.; Kumar, A. An evaluation of self-organizing map networks as a robust alternative to factor analysis in data mining applications. Inf. Syst. Res. 2001, 12, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippopoulos, K.; Deligiorgi, D.; Kouroupetroglou, G. Performance comparison of self-organizing maps and k-means clustering techniques for atmospheric circulation classification. Int. J. Energy Environ. 2014, 8, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, O. Comparisons between data clustering algorithms. Int. Arab J. Inf. Technol. 2008, 5, 320–325. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell, M.; Fort, J.; Pagès, G. Theoretical aspects of the SOM algorithm. Neurocomputing 1998, 21, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaski, S. Data exploration using self-organizing maps. In Acta Polytechnica Scandinavica: Mathematics, Computing and Management in Engineering Series No. 82; Finnish Academy of Technology: Espoo, Finland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, P.B.; Uotila, P.; Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.E.; Alexander, L.V.; Pitman, A.J. Evaluating synoptic systems in the CMIP5 climate models over the Australian region. Clim. Dyn. 2016, 47, 2235–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, J.C.; Letremy, P.; Cottrell, M. Advantages and drawbacks of the Batch Kohonen algorithm. In Proceedings of the European Symposium on Artificial Neural Networks ESANN, Bruges, Belgium, 24–26 April 2002; pp. 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Uriarte, E.A.; Martín, F.D. Topology preservation in SOM. Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2005, 1, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens, R.; Kruisselbrink, J. Flexible self-organizing maps in kohonen 3.0. J. Stat. Softw. 2018, 87, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnston, A.G.; Livezey, R.E. Classification, seasonality and persistence of low-frequency atmospheric circulation patterns. Mon. Weather Rev. 1987, 115, 1083–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowienka-Hense, R. The North Atlantic Oscillation in the Atlantic-European SLP. Tellus A 1990, 42, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, H.; Rogers, J.C. The seesaw in winter temperatures between Greenland and Northern Europe. Part I: General description. Mon. Weather Rev. 1978, 106, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wallace, J.M.; Gutzler, D.S. Teleconnections in the geopotential height field during the Northern Hemisphere winter. Mon. Weather Rev. 1981, 109, 784–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steirou, E.; Gerlitz, L.; Apel, H.; Merz, B. Links between large-scale circulation patterns and streamflow in Central Europe: A review. J. Hydrol. 2017, 549, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafik, L.; Nilsen, J.E.O.; Dangendorf, S. Impact of North Atlantic teleconnection patterns on Northern European sea level. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2017, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Der Wiel, K.; Bloomfield, H.C.; Lee, R.W.; Stoop, L.P.; Blackport, R.; Screen, J.A.; Selten, F.M. The influence of weather regimes on European renewable energy production and demand. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 094010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.C. How many ENSO flavors can we distinguish? J. Clim. 2013, 26, 4816–4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon-Kidd, D.C. On the classification of different flavours of Indian Ocean Dipole events. Int. J. Clim. 2018, 38, 4924–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, M.; Radebach, A.; Donges, J.F.; Kurths, J.; Donner, R.V. A climate network-based index to discriminate different types of El Niño and La Niña. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 7176–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, W.Y.; Dool, H.V.D. Sensitivity of teleconnection patterns to the sign of their primary action center. Mon. Weather Rev. 2003, 131, 2885–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portis, D.H.; Walsh, J.E.; El Hamly, M.; Lamb, P.J. Seasonality of the North Atlantic Oscillation. J. Clim. 2001, 14, 2069–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, S.; Piontkovski, S. The dominant influence of the Icelandic Low on the position of the Gulf Stream northwall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, 1998–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.W.K.; Renfrew, I.A.; Pickart, R.S. Multidecadal mobility of the North Atlantic Oscillation. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 2453–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zubiate, L.; Mcdermott, F.; Malley, M.O. Spatial variability in winter NAO—Wind speed relationships in western Europe linked to concomitant states of the East Atlantic and Scandinavian patterns. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 143, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castro-Díez, Y.; Pozo-Vazquez, D.; Rodrigo, F.S.; Esteban-Parra, M.J. NAO and winter temperature variability in southern Europe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2002, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, H.W.; Richling, A.; Bissolli, P.; Ulbrich, U. Linking teleconnection patterns to European temperature—A multiple linear regression model. Meteorol. Z. 2015, 24, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.M.; Yeager, S.; Chang, P.; Danabasoglu, G. Atmospheric conditions associated with Labrador Sea deep convection: New insights from a case study of the 2006/07 and 2007/08 winters. J. Clim. 2016, 29, 5281–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delworth, T.L.; Zeng, F. The impact of the North Atlantic Oscillation on climate through its influence on the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. J. Clim. 2016, 29, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, A.L.; Rahmstorf, S.; Robinson, A.; Feulner, G.; Saba, V. Title: Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nature 2018, 556, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; López-Moreno, J.I. Nonstationary influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation on European precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2008, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Luo, D. Relationship between zonal position of the North Atlantic Oscillation and Euro-Atlantic blocking events and its possible effect on the weather over Europe. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2014, 57, 2628–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T. The North Atlantic Oscillation: Variability and Interactions with the North Atlantic Ocean and Arctic Sea Ice; Christian-Albrechts-Universität: Kiel, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, K.A.; Derome, J.; Greatbatch, R.J.; Lu, J.; Lin, H. Hindcasting the NAO using diabatic forcing of a simple AGCM. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2002, 29, 50–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Hilmer, M.; Ruprecht, E.; Kleppek, S.; Gulev, S.K.; Zolina, O. Characteristics of the recent eastward shift of interannual NAO variability. J. Clim. 2003, 16, 3371–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peterson, K.A.; Lu, J.; Greatbatch, R.J. Evidence of nonlinear dynamics in the eastward shift of the NAO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Both Periods | P (1971–2000) | F (2071–2100) | Freq Differences F-P | Persistence Differences F-P | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAO Flavor | Freq (per NAO Days) | Mean Persistence (Max. Pers.) | NAO Flavor | Freq (per NAO Days) | Trend | Mean Persistence (Max. Pers.) | NAO Flavor | Freq (per NAO Days) | Trend | Mean Persistence (Max. Pers.) | ||

| W+ | 6.1% | 2 (7) | W+ | 5.1% | − | 1.7 (4) | W+ | 6.9% | − | 2.4 (7) | 1.8% | 0.7 (3) |

| WE+ | 12.3% | 2.2 (10) | WE+ | 13.5% | + | 2.4 (10) | WE+ | 11.1% | + | 2 (6) | −2.4% | −0.4 (−4) |

| E+ | 28.7% | 2.9 (13) | E+ | 29.0% | + | 3.5 (13) | E+ | 28.4% | + | 2.5 (12) | −0.6% | −1 (−1) |

| EW+ | 9.5% | 2.3 (9) | EW+ | 10.7% | − | 2.1 (6) | EW+ | 8.3% | + | 2.5 (9) | −2.4% | 0.3 (3) |

| Total NAO+ | 56.5% | 2.4 (13) | Total NAO+ | 58.3% | 2.4 (13) | Total NAO+ | 54.7% | 2.4 (12) | −3.5% | 0 (−1) | ||

| W− | 13.4% | 2.8 (10) | W− | 14.2% | − | 3.2 (10) | W− | 12.6% | − | 2.5 (9) | −1.6% | −0.7 (−1) |

| WE− | 7.6% | 3.2 (10) | WE− | 6.3% | + | 3.7 (9) | WE− | 8.8% | − | 2.9 (10) | 2.5% | −0.8 (1) |

| E− | 22.6% | 3.4 (11) | E− | 21.2% | + | 3 (10) | E− | 23.8% | − | 3.8 (11) | 2.7% | 0.8 (1) |

| Total NAO− | 43.5% | 3.1 (11) | Total NAO− | 41.7% | 3.3 (10) | Total NAO− | 45.3% | 3.1 (11) | 3.5% | −0.2 (1) | ||

| Action Center | Shift Direction | NAO+ | NAO− | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency % per All Days (% per NAO Days) | Average Displacement (Max. Displ) | Frequency % per All Days (% per NAO Days) | Average Displacement (Max. Displ) | ||

| Icelandic Low | Eastern | 12% (40%) | 23° (39°) | 7% (25%) | 17° (56°) |

| Western | 6% (18%) | 11° (23°) | 7% (21%) | 11° (28°) | |

| Azores High | Eastern | 12% (37%) | 35° (54°) | 9% (30%) | 26° (53°) |

| Western | 5% (17%) | 11° (21°) | 4% (13%) | 11° (21°) | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rousi, E.; Rust, H.W.; Ulbrich, U.; Anagnostopoulou, C. Implications of Winter NAO Flavors on Present and Future European Climate. Climate 2020, 8, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8010013

Rousi E, Rust HW, Ulbrich U, Anagnostopoulou C. Implications of Winter NAO Flavors on Present and Future European Climate. Climate. 2020; 8(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleRousi, Efi, Henning W. Rust, Uwe Ulbrich, and Christina Anagnostopoulou. 2020. "Implications of Winter NAO Flavors on Present and Future European Climate" Climate 8, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8010013

APA StyleRousi, E., Rust, H. W., Ulbrich, U., & Anagnostopoulou, C. (2020). Implications of Winter NAO Flavors on Present and Future European Climate. Climate, 8(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8010013