1. Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that property rights and ownership structure are crucial elements of the firm theory [

1,

2]. As ownership dispersion has become a feature of the modern corporation, the understanding of how this may be a source of internal conflict for the firm has been examined in the literature since the seminal work of Berle and Means [

3]. There is a growing interest in the literature related to the analysis of how firms with ownership concentration, particularly in family groups, face these challenges, and the effects that particular ownership structures have on firm performance [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The importance of family firms in national economies is even more evident in emerging economies, where it has been measured in terms of contribution to gross domestic product, employment, and number of firms [

12,

13]. It has been shown that family businesses possess some features that lead to better performance when compared to non-family firms [

14]. As in most developing countries, the majority of companies in Mexico are considered family firms [

15]. However few studies refer specifically to Mexican family businesses, thus the importance for further investigation [

2,

15]. As Gedajlovic, Carney, Chrisman, and Kellermanns [

6] discuss, it is important to further analyze this phenomenon in emerging countries, where some contextual and institutional factors may fill voids in particular institutional contexts where underdeveloped capital markets and weak corporate legal enforcement prevail.

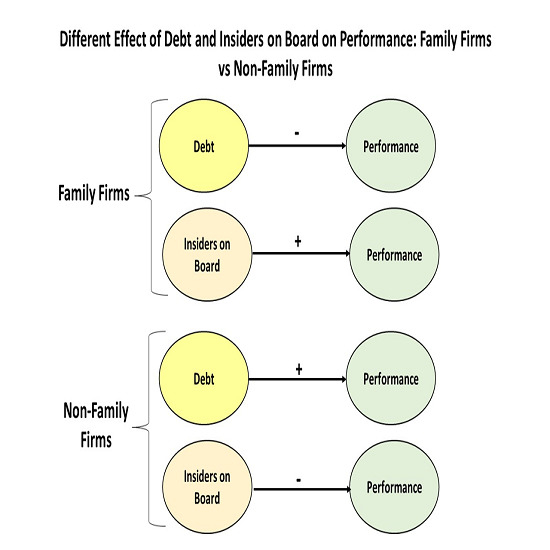

Many studies have focused on comparing the performance of family

versus non-family firms, however, this research is more focused on building upon the knowledge of factors that differ in family and non-family firms, and how they influence performance in both types of firms. Thus, the study focuses on debt and board structure and their effect on performance in family and non-family firms. Studying both family and non-family firms will permit the observation of how family firms choose to lessen agency problems by means of increasing leverage to reduce unrestricted funds for managers and the number of outside directors to reduce nepotism and entrenchment [

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, these same measures may lead to situations where family firms are not prepared to assume risks that affect their socioemotional wealth [

18]. Observing the effects of leverage and board structure on non-family firm performance is an important comparison as, even though these companies also often have high ownership concentration in Mexico, they may tend to choose different strategies to reign in managers.

This research analyzes the relationship between ownership concentration in Mexican listed firms and performance. The study contributes to the literature by further observing contextual and institutional factors, which when added to the abovementioned relationship, are expected to have different repercussions on family and non-family firms. The sample is separated into family and non-family firms so as to demonstrate the different influences that debt and board structure have on firm performance.

The following section includes a review of the literature on ownership concentration and performance, and on debt and board structure as some of the most relevant factors that are associated with performance in family and non-family firms. Next, the methodology presents a description of the sample, data collected, variables defined, and the regression analysis conducted, followed by the presentation of the results. In the last section, discussion of results and conclusions are presented, highlighting the main contributions and limitations of this study as well as proposing some lines of further related research.

3. Methodology

The initial sample used in this study comprised all of the 142 firms listed on the Mexican Stock Exchange during the periods of 2005–2011. Those firms that did not provide sufficient information for comparison purposes in their financial statements were eliminated from the study. Also, financial institutions and nonprofit organizations were excluded as well given the difficulties for the estimation of Tobin’s Q for financial institutions and non-comparable issues for the nonprofit organizations. The final sample consisted of 75 companies whose annual reports and financial information were collected from Economatica and Isi Emerging Markets. Finally, from the Mexican Stock Exchange website, information concerning industrial sectors was collected as well. The companies in the sample classified by industrial sector are shown in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Number and percent of family and non-family firms by sector.

Table 1.

Number and percent of family and non-family firms by sector.

| Sector | Total |

|---|

| Materials | 16 |

| Industrial | 21 |

| Services and goods of consumer non-basic | 14 |

| Common consumer products | 13 |

| Health | 4 |

| Telecommunications services | 7 |

| Total | 75 |

The companies in the sample are basically medium to large companies compared with the average Mexican firm size, either in terms of assets, sales or employees. This could raise some caveats about a possible sample bias, notwithstanding, the Panel A of

Table 2 descriptive statistics show that firm size (in terms of assets) is quite heterogeneous and highly dispersed around the mean value, so it is assumed that the results are not biased by size issues. The sample composition is quite industry-balanced, although there is a slight bias towards industrial and materials firms at the expense of health or telecommunications companies that can be explained by the heavier concentration of the former in the Mexican market.

Table 2.

Descriptive data.

Table 2.

Descriptive data.

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics for all firms |

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| Q | 1.40 | 0.76 | 0.25 | 4.38 |

| Famown | 0.51 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.98 |

| Lev | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 5.74 |

| Ind | 4.23 | 2.33 | 1 | 11 |

| Sha | 5.37 | 2.14 | 0 | 14 |

| β | 0.67 | 1.14 | −5.89 | 7.20 |

| Size | 56,298.7 | 150,249 | 263 | 1,277,397 |

| Panel B: Descriptive statistics by ownership structure |

| Family | Non-Family |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| Q | 1.36 | 0.73 | 0.25 | 4.38 | 1.54 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 4.23 |

| Lev | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 1.21 |

| Ind | 4.4 | 2.34 | 0 | 9 | 6.14 | 2.94 | 2 | 14 |

| Sha | 5.14 | 2.17 | 0 | 11 | 3.69 | 2.23 | 0 | 9 |

| β | 0.66 | 1.12 | −5.89 | 6.61 | 0.69 | 1.22 | −5.28 | 7.20 |

| Size | 38,403 | 57,665 | 405 | 349,121 | 21,931 | 29,235 | 263 | 155,061 |

A key aspect of this study is the identification of family and non-family firms. Since the study focuses on ownership concentration, and family firms typically have more concentrated ownership, especially in non-Anglo-Saxon countries [

72], it is important to identify the proper threshold of ownership that divides family and non-family firms in our sample in order to observe the effects of debt and board structure.

Mazzi, in her 2011 study [

8] on 23 different research articles in different countries, states that owning families typically demonstrate a minimum control of 5, 10, or 20 percent, however, she later finds in her research that the median degree of family control among three-digit SIC industries is 50 percent when family firms are founder or founding family owned, and 51 percent when they are defined as individual or family controlled. La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Schleifer, and Vishny [

25,

77], in a sample of large non-financial firms in 49 countries, find that the average ownership by the three largest shareholders is 46 percent. San-Martin and Duran [

11] consider a firm a family firm as long as the family has 40 percent or more ownership of the company, as this percentage gives the family the ability to control the decisions and management of the company.

Since companies in general have a higher ownership concentration in Mexico, the choice of a higher starting concentration in order to properly divide the sample seems appropriate in this research, unlike other studies in which companies are classified as family companies when the owning family controls only 20 or 30 percent of the firm. Therefore, this study defines a family as one having an ownership concentration above 40 percent.

The percentage of ownership concentrated by the family was expressed as

Famown and the Tobin’Q, or the asset market-to-book ratio, as

Q. The remaining variables are leverage (

Lev), which is measured as the book value of debt divided by the book value of total assets; and the board composition made of the number of independent (

Ind) and insider or shareholder (

Sha) directors. In addition, some control variables were included in order to examine some additional determinants of performance. Based on what has been done in previous works [

31,

78,

79,

80], the analysis considered size (

Size)

, as represented by firm’s total assets, the natural logarithm of size (

Lsize)

, and market risk (

β)

. As stated before, the sample combines 75 firms over seven years producing a 525 observations-panel data. Given the aim of the study, the panel data methodology seems to be the most accurate [

39]. The fixed-effects term is unobservable, and hence becomes part of the random component in the estimated model. A pooling analysis of all the companies without noticing these peculiar characteristics could cause an omission bias and distort the results. The random error term εit controls both the error in the measurement of the variables and the omission of some relevant explanatory variables. The models can be expressed by the following equations, where

refers to the firms and

to the year (

= 1,….,75;

= 1,….,7):

To provide robustness for the results, the percentage of ownership concentration to classify a company as a family or non-family firm was modified, using an ownership concentration level of 51 percent. It is important to mention that an attempt was made for an additional analysis using 35 percent as the ownership concentration level, but unfortunately, the Mexican market is characterized by high concentration across the board and at 35 percent of ownership concentration family firms represented 85 percent of the sample.

Also, to avoid the endogeneity problem in the relationship of family ownership and performance, the data was examined with the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) that eliminates the possibility of second order serial correlation in the moments considered in the sample [

81,

82,

83]. All regressors in the regression method are considered as exogenous except the lagged variable. The application of the Sargan test allows proving these conditions by avoiding incurring type I error, or accepting the null hypothesis. Thus, GMM provides mechanisms to limit errors over time, and to deal with heterocedasticity and simultaneity among the cases [

31].

Finally, the effect of debt and board composition on performance was proved for first, second, and third or later generations of family firms, to examine if the results obtained for the whole sample of family firms vary. In this manner, the study tried to examine if the risk aversion and other motivations of family firms vary as the generation in control changes [

57,

58].

As shown in

Table 2, on the one hand, family firms have a higher number of shareholders as board directors, and have more assets, while on the other hand, family firms have lower market performance, lower relative debt, fewer independent directors, and lower market risk.

4. Results

The results of the panel data estimation are displayed in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5. These were estimated not only for the basic specification (Panels A and B of

Table 4), but also segmenting the sample by alternative measure of ownership structure, with a level of ownership concentration in families to 51 percent, in order to assess robustness of the results (

Table 5). The Hausman test reveals the importance of the fixed effect component, so that within-groups estimation method becomes necessary in order to deal with the constant unobservable heterogeneity.

Table 3.

Results of estimation based on complete sample.

Table 3.

Results of estimation based on complete sample.

| Variables | Coefficient | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|

| Famown | 0.6026 | 1.71 | 0.088 *** |

| Lev | −0.2156 | −1.88 | 0.061 *** |

| Ind | −0.4088 | −1.22 | 0.221 |

| Sha | 0.6669 | 2.11 | 0.035 ** |

| β | 0.088 | 0.46 | 0.644 |

| Lsize | 0.0607 | 0.88 | 0.381 |

| Constant | 0.4179 | 0.57 | 0.566 |

| Adjusted R² | 0.25 | | |

| Hausman test | 32.57 | | 0.000 |

According to

Table 3, there is a positive significant statistical association of family ownership with Tobin’s Q, which represents market performance, confirming the first hypothesis. Also, the participation of shareholders on the board is positively associated to performance in a significant way. The level of indebtedness is associated negatively to performance.

Further analysis observes the effect that these variables have on company performance or value creation after differentiating between family and non-family firms. The results are shown in

Table 4.

Table 4 shows the effect that debt and board structure have on market performance considering family and non-family firms. Whereas lower levels of debt are associated in a significant way to higher market performance in family firms, higher levels of debt are related to superior performance in non-family businesses. Both results confirm hypotheses 2a and 2b.

Table 4.

Results of estimations based on family and non-family sample (family holds more than 40 percent ownership).

Table 4.

Results of estimations based on family and non-family sample (family holds more than 40 percent ownership).

| Panel A: Family Firms | Panel B: Non-Family Firms |

|---|

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|

| Lev | −0.210 | | | −0.211 | 0.282 | | | 0.211 |

| (−1.94) ** | | | (−1.95) ** | (2.72) ** | | | (1.95) ** |

| Ind | | −0.188 | | −0.188 | | 0.559 | | 0.562 |

| | (−1.80) * | | (−1.80) * | | (2.06) ** | | (1.97) ** |

| Sha | | | 0.685 | 0.608 | | | −0.120 | −0.117 |

| | | (1.94) ** | (2.18) ** | | | (−2.20) ** | (−2.10) ** |

| β | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.019 | 0.050 | 0.071 |

| (0.80) | (0.91) | (0.67) | (0.74) | (0.25) | (0.47) | (0.21) | (0.79) |

| Lsize | 0.115 | 0.094 | 0.077 | 0.123 | 0.123 | 0.188 | 0.236 | 0.138 |

| (1.67) * | (1.37) | (1.13) | (1.76) * | (0.56) | (1.01) | (1.21) | (1.65) |

| Constant | 0.327 | 0.712 | 0.460 | 0.920 | 0.812 | 0.442 | 0.452 | 0.580 |

| (0.50) | (1.06) | (0.70) | (1.25) | (0.35) | (1.32) | (2.37) ** | (1.35) |

| Adjusted R² | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Hausman test | 20.17 | 23.10 | 31.42 | 36.49 | 15.58 | 22.09 | 29.31 | 24.78 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.008) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

In the case of the structure of the board, the results show a significant positive relationship for inside directors and performance and a negative relationship for external board directors in family firms. Just the opposite is true for non-family firms, as performance is affected negatively by the presence of shareholders on the board and positively by independent director participation, thus hypotheses 3a and 3b are confirmed.

In all cases, market risk and firm size are positively associated with market performance, but only in the case of the family firm, size as measured as the amount of assets, shows a significant relationship.

The results of the regression analysis using 51 percent of family ownership as the threshold for defining family firms

versus non-family firms are shown in

Table 5.

The results shown in

Table 5, using 51 percent for differentiating a family from a non-family firm, do not differ from the results in

Table 4. This means that the results may apply for an extended range of ownership concentration.

Table 5.

Results of estimations based on family and non-family sample (family holds more than 51 percent ownership).

Table 5.

Results of estimations based on family and non-family sample (family holds more than 51 percent ownership).

| Panel A: Family Firms | Panel B: Non-Family Firms |

|---|

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|

| Lev | −0.067 | | | −0.062 | 0.144 | | | 0.234 |

| (−1.78) * | | | (−1.72) * | (1.92) ** | | | (1.73) * |

| Ind | | −0.109 | | −0.138 | | 0.403 | | 0.685 |

| | (−1.94) ** | | (−1.67) * | | (1.73) * | | (1.99) ** |

| Sha | | | 0.620 | 0.684 | | | −0.203 | −0.164 |

| | | (1.68) * | (2.19) ** | | | (−1.72) * | (−1.67) * |

| β | 0.047 | 0.059 | 0.061 | 0.060 | −0.056 | −0.030 | −0.027 | −0.061 |

| (2.09) ** | (2.13) ** | (2.18) ** | (2.25) ** | (−1.15) | (−0.83) | (−0.73) | (1.17) |

| Lsize | 0.246 | 0.230 | 0.209 | 0.246 | 0.359 | 0.279 | 0.267 | 0.138 |

| (3.59) *** | (3.19) *** | (2.83) *** | (3.58) *** | (2.14) ** | (1.78) ** | (1.70) * | (1.65) |

| Constant | 0.934 | 0.909 | 0.861 | 0.961 | 0.426 | 0.567 | 0.359 | 0.328 |

| (1.49) | (1.35) | (1.15) | (1.98) ** | (2.49) ** | (3.11) *** | (1.70) * | (1.91) ** |

| Adjusted R² | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.21 |

| Hausman test | 22.36 | 23.42 | 21.53 | 39.12 | 15.29 | 21.19 | 28.71 | 29.34 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

In order to deal with endogeneity, the results of the GMM model are shown in

Table 6.

Table 6 shows that after controlling for endogeneity, and failing to reject the null hypothesis, results remain as already reported in previous regressions. This demonstrates the robustness of the results, reinforcing the hypotheses of this study.

The results of differentiating the effect of debt and board structure in first, second, and third or later generations of family firms are presented in

Table 7.

The first and second generations of family firms show that higher performance associates with less debt, whereas in third or later generations, performance is linked to more debt. In the case of board structure, there is also a modification between the first two family firm generations and the third or later generations, as the association of independent directors with performance changes from negative to positive.

Table 6.

Results of GMM Model based on family and non-family sample (family holds more than 51 percent ownership).

Table 6.

Results of GMM Model based on family and non-family sample (family holds more than 51 percent ownership).

| Variable | Panel A: Family Firms | Panel B: Non-Family Firms |

|---|

| Constant | 0.598 | 0.351 |

| (0.32) | (1.42) |

| Lev | −0.420 | 0.718 |

| (−2.29) ** | (1.96) ** |

| Ind | −0.974 | 0.501 |

| (−2.28) ** | (2.02) ** |

| Sha | 0.297 | −0.246 |

| (1.82) * | (−2.02) ** |

| β | 0.074 | 0.090 |

| (1.78) * | (1.42) |

| Lsize | 0.190 | 0.117 |

| (0.96) | (0.53) |

| m1 | −6.21 *** | −5.34 *** |

| m2 | −0.68 | −0.71 |

| Sargan test | 9.13 | 8.53 |

| Wald test | 12.36 * | 13.51 * |

Table 7.

Results of estimations based on generation family sample (first generation and second or more generations).

Table 7.

Results of estimations based on generation family sample (first generation and second or more generations).

| Variable | PGEN | SGEN | TGEN |

|---|

| Lev | −0.557 | −0.168 | 0.221 |

| (2.53) *** | (−1.80) * | (2.87) *** |

| Ind | −0.2937 | −0.808 | 0.560 |

| (−2.16) ** | (−1.86) * | (1.81) * |

| Sha | 0.8570 | 0.774 | −0.338 |

| (3.47) *** | (1.91) ** | (−1.99) ** |

| β | 0.090 | 0.087 | 0.082 |

| (0.27) | (0.20) | (0.19) |

| Lsize | 0.109 | 0.384 | 0.256 |

| (1.96) ** | (2.15) ** | (1.40) |

| Constant | 0.313 | 0.496 | 0.721 |

| (1.74) * | (1.39) | (0.48) |

| Hausman test | 25.76 | 21.34 | 23.56 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study focuses on the role corporate governance plays in the relationship between ownership structure and performance. In particular, it deals with two mechanisms of corporate governance, externally, the level of debt in a firm, and internally, the structure of the firm’s board.

From a theoretical point of view, the results of this study add to the relationship of ownership concentration and performance, indicating the reductions of agency costs given the weak corporate legal governance in Mexico. Thus, owners may assure by these means greater control of their firms.

Through the investigation of the level of debt and the composition of the board of directors, this study disentangles some findings that point to ambiguous or contradictory associations between family and non-family firms, and performance. The answers to the hypotheses that were formulated in this study lead to the conclusion that in both family and non-family cases, the financial leverage and the board structure act as reinforcing mechanisms in the achievement of better results.

The findings show that in family businesses, the avoidance of debt and the greater participation of dominant shareholders on the board act as regulatory mechanisms for better performance. Given the high concentration of property in family firms, debt is not seen as a necessary mechanism for reducing discretionary management behavior. This discretionary management behavior is limited by the control rights that owners exercise on discretionary funds. It is also likely that by reducing the level of debt, owners can reduce perception of the risk of financial bankruptcy and loss of control, strengthening the socioemotional goals maintained by a closer family group of owners. On the contrary, the dispersion of property may encourage owners to increase the level of debt as this mechanism would serve as a monitor to make better use of funds in profitable projects, leading to a better return on equity capital.

When there is a high concentration of property, the role of shareholders becomes more important for the firm. Majority shareholders are able to improve the firm’s position by minimizing the risk of being distracted by the goals of fewer and less important minority shareholders. Apparently, according to the performance achieved by family businesses in this study, the presence of entrenchment or nepotism does not seem to be a common issue in these firms. Therefore, it may seem that stewardship in company management is best performed when owners in governance bodies maintain higher authority and discretion. The benefits that owners obtain by exercising their control rights on the board are effective in achieving better performance. In the opposite situation, when ownership is more dispersed, the role of independent directors on the board becomes more relevant. It can be argued that in the case of non-family businesses, independent directors are in a better position to provide more objective and informed advice than family shareholders. The higher dispersion of property may bias board decisions toward the dominant shareholder block, compromising a more comprehensive view of the firm. As other related studies have shown [

11], in non-family firms, institutional investors, such as financial institutions, participate to a larger extent. This participation may increase the board’s capabilities for monitoring free cash flow use in the firm, and also may serve as a mechanism to reduce risk aversion caused by macroeconomic volatile changes.

The association of debt and board structure with the generation in control shows that debt may become an effective mechanism, as there is dispersion in ownership and a consequent reduction of risk aversion in third and later generations [

57]. The same arguments may apply to the growing number of independent directors on the board as their participation becomes more credible, acting as a more effective representation of minority shareholders [

7,

9]. This situation is explained by Schulze, Lubatkin, and Dino [

57], who argue that the greater the ownership dispersion, and the smaller the average shareholding, the more likely their boards will favor growth, and, in the absence of the ability to issue equity or cut dividends, the more likely they will be to risk the use of debt to fund growth.

From a practical perspective, the differentiated effect of those factors may serve to fill the institutional voids mentioned by Gedajlovic

et al. [

6], mainly the weak protection allowed to minority investors in Mexico. As previously mentioned, the reinforcement effect of having a low debt and low participation of independent directors in family businesses, contributes to the association of family ownership with better performance, especially in a context where there is weak legal corporate shareholder protection, such as in emerging economies. By the same token, in the case of non-family businesses, the participation of independent or external directors on the board and a higher level of debt act as an effective device to achieve better performance.

However, the relatively lower average market performance of family firms as compared to non-family firms (see

Table 2) may be affected by the strategies they follow in relation to indebtedness, which in some cases may cause underinvestment to support growth and profitability. Thus, in order to make better use of their potential, family firms are encouraged to create organizational structures and decision rules that facilitate intra-family communication; including the involvement of family members in the top management of the firm and professional advisors may help as well [

37]. Additionally, it can be found that views and orientations of outsiders and owners can strengthen the firm’s board. As Cannella, Jones, and Whiters [

84] have shown, firms may seek directors with prior experience at firms with similar identities that are mainly

familial or

entrepreneurial in nature. For practical implications, recommendations can be directed to family owners to seek directors that have a close identity with the organization [

85], and who have the experience and power to counsel an otherwise entrenched family leader [

86].

We are aware of the limitations of this study, as the results may be only valid for Mexico and possibly for those countries in which there is a relatively high concentration of firm property. Also, we recognize that we have found an association between debt and board composition, and the results obtained in family and non-family firms, however, to show causality would require a longitudinal research design.

In spite of these considerations, the main contributions of this study include an important understanding of the relationship of debt and board structure, and also a simultaneous analysis of the effect of these variables in family and non-family businesses. With these findings, we seek to encourage similar research in other emerging economies to further explain the relationship between ownership concentration and performance.