6.1. 2-Copy Joint Observables from Mixing

Let , and be the three sharp spin- observables on , with outcome spaces . We further denote for , and similarly, and for . These are considered as noisy (unsharp) versions of the sharp observables , and , with noise intensities and , respectively.

Furthermore, let us define three observables:

These observables, parametrized by the angles

α,

β and

γ, will be useful in constructing joint observables later.

We recall the following results on joint measurability of noisy spin-

observables [

4].

Theorem 2. The following facts hold.- (1)

and are compatible if and only if .

- (2)

, and are compatible if and only if .

In particular, we see that the marginals of the observables , and are noisy versions of the couples , and , respectively, with noise intensities attaining the upper bound of Item (1) of Theorem 2.

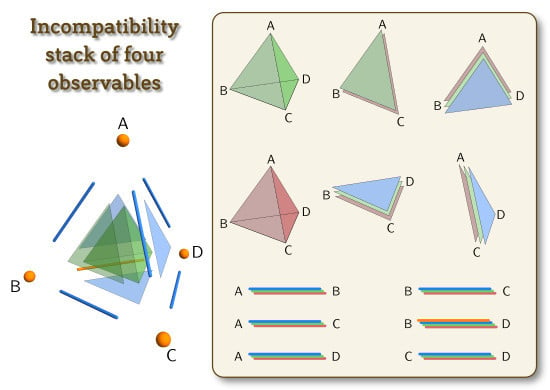

From these results, we already find realizations of the cases (a)–(d) in

Figure 2. For instance, with the following choices of the parameters

a,

b and

c, we get suitable triples of observables:

- (a)

, with joint observable

for the triple

,

and

;

- (b)

, with joint observables , and for the corresponding pairs of observables;

- (c)

and , with joint observable (having and ) for observables and and joint observable (having and ) for observables and ;

- (d)

, and , with joint observable (having and ) for observables and .

The cases (e) and (f) are more involved, and the rest of the section is dedicated to them; let us see how far we can get by mixing joint observables of two observables. The method is as follows. We choose randomly either , or , measure the chosen observable, say , on the first system and then an optimal joint observable of the noisy versions of the remaining observables and on the second system. This gives the following sufficient condition for 2-compatibility.

Proposition 3. (Sufficient condition for 2-compatibility) ,

and are 2-compatible if there are numbers and ,

such that:and: Proof. We choose randomly either

,

or

, measure the chosen observable, say

, on the first system and then the optimal joint observables

of the noisy versions of the remaining observables

and

on the second system. The total procedure leads to an observable:

where

represent the probabilities for the choice of the measurement

, respectively. It is easy to check that

is a 2-copy joint observable of the three observables

,

and

, with

a,

b and

c attaining the upper bounds from (8). ☐

Using Proposition 3, we can cook up a realization of

Figure 2e. The 2-compatibility of

,

and

can be achieved by setting

and

. This choice provides a possible setting (in

Figure 2):

- (e)

.

6.2. Optimal 2-Copy Joint Observable

To find a realization of the compatibility stack depicted in

Figure 2f, we need to show that

,

,

are not 2-compatible for some values of noise intensities

. The fact that these kind of parameters exist follows from the next theorem.

Theorem 3. , and are 2-compatible if and only if .

By Theorem 1, the observables

,

and

are 2-compatible if and only if the observables

,

and

have a symmetric joint observable

, where:

and similarly for

and

. We will now show that

can be chosen to be covariant with respect to the transitive action of a suitable group on the joint outcome space

of the three observables

,

and

. Covariance will then drastically decrease the freedom in the choice of

, actually reducing it to only fixing two parameters. To exploit covariance, we start from the following simple fact.

Proposition 4. Suppose G is a finite group, Ω

is a G-space and U is a unitary representation of G in the Hilbert space .

Let be a collection of subsets of Ω,

such that:Then, for any observable :

satisfying the relation:the observable :

given by:is such that:- (i)

for all and ;

- (ii)

for all .

Proof. Direct verification. ☐

According to (10), we call the observable the U-covariant version of .

The choice of the covariance group G and its action on the outcomes Ω for a joint observable of , and is prescribed by the covariance properties of , and . Namely, the set of effects is invariant for the rotations in the octahedron subgroup . Moreover, O acts transitively on this set. We therefore expect that the proper covariance group for our problem is . We now explain this statement in more detail.

The octahedron group O is the order 24 group of the 90° rotations around the three coordinate axes , together with the 120° rotations around the axes and the 180° rotations around , and . It preserves the set and acts transitively on it. Moreover, the stabilizer subgroup of any is just the subgroup of the three 120° rotations around .

The octahedron group also acts on the spin- Hilbert space by restriction of the usual two-valued -representation of . This gives an ordinary representation of O on the 2-copy Hilbert space , where is any of the two elements of corresponding to the rotation .

Finally, let

:

be the projection onto the

i-th component (

) and define the collection of subsets:

Clearly, the collection

is

O-invariant. Moreover, if

:

is any symmetric joint observable of

,

and

, then:

The covariance properties of the observables

,

and

then imply that

for all

and

. Hence, by Proposition 4, the

U-covariant version

of

defined in (10) yields the same margins

,

and

. Since the representations

U of

O and

σ of

commute, the joint observable

is both

U-covariant and symmetric.

In summary, in order to find the maximal value of a for which the observables , and are 2-compatible, we are led to classify the family of symmetric U-covariant observables on Ω. This is done in the next proposition.

Proposition 5. A map is a symmetric and U-covariant observable if and only if there exist real numbers α and β with ,

and ,

such that:for all .

Proof. We will proceed in several steps.

(I) Since the action of

O on Ω is transitive, a

U-covariant observable

is completely determined by its value at

by the relation:

This equation implies that

must commute with the representation

U restricted to the stabilizer

of

. This happens if and only if

is in the commutant

of the operator

, where

. The eigenvalues of

are

and

with multiplicity one, and 1 with multiplicity two. Hence,

. A linear basis of

is made up of the self-adjoint operators:

Among them,

,

,

and

are symmetric, and

and

are antisymmetric. Thus,

is symmetric only if

is a real linear combination of

,

,

,

. This is also a sufficient condition for the symmetry of

by (12) and the symmetry of the

’s.

(II) It is easy to check that the operators

,

,

and

all commute among themselves. Moreover,

Thus, the four self-adjoint operators:

are mutually commuting orthogonal projections summing up to the identity of

. It follows that

,

,

,

are rank-one mutually orthogonal projections. Since they span the same linear space as

, we can rewrite:

where:

by the positivity condition

. This is also a sufficient condition for the positivity of

by (12).

(III) By taking the trace of the normalization condition:

and observing that

, we obtain:

Moreover, the operators

and

commute with the representation

U, hence so does the rank-one projection

. Multiplying both the sides of (15) by

and taking again the trace, we then get:

Inserting (13) into (16) and (17) yields the conditions:

The positivity requirement (14) thus translates into:

and (13) is rewritten as:

We have already seen that

commutes with

for all

. Therefore, the formula (11) follows from the previous equation by the relation (12). We still need to check that

given by (11) is normalized, and this easily follows from:

☐

Remark 1. The choice of the covariance group and its natural action on the joint outcome space Ω is the minimal possible in order to construct a transitive action of G on Ω preserving the set of effects . Transitivity is needed in order to label all of the covariant joint observables by means of the single operator as in (12) and, thus, reduce the many free parameters of the problem to the only choice of such an operator.

Now, we need to take the three margins of the most general

U-covariant observable found in Proposition 5 and compare it with the observables

,

and

. By the covariance property, it is sufficient to consider only the first margin

. We have:

and hence:

Comparing this formula with (9) yields:

By the positivity conditions

,

and

, we thus see that the maximal value of

a is

. This completes the proof of Theorem 3.

As a result, the case (f) of

Figure 2 can now be achieved for example by setting:

- (f)

,

though any choice larger than

suffices.

By combining the result of Theorem 3 with that of Theorem 2 in the case

, we get a complete characterization of the index of incompatibility for three equally noisy orthogonal qubit observables

,

and

. In

Figure 5, the index of incompatibility

is plotted as a function of the noise parameter

a.