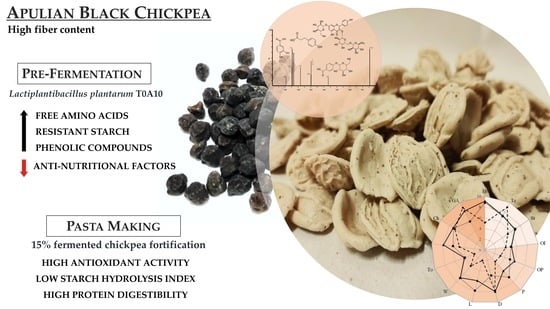

Nutritional and Functional Advantages of the Use of Fermented Black Chickpea Flour for Semolina-Pasta Fortification

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials and Microorganisms

2.2. Fermentation

2.3. Doughs Characterization

2.3.1. Microbiological Analysis

2.3.2. Biochemical Characterization

2.3.3. In Vitro Protein Digestibility

2.3.4. Antioxidant Activity

2.3.5. Extraction, Identification and Quantification of Free and Bound Phenolic Compounds

2.3.6. Antinutritional Factors

2.4. Pasta Making

2.5. Pasta Characterization

2.5.1. Hydration Test, Cooking Time, Cooking Loss and Water Absorption

2.5.2. Biochemical Characterization and Antioxidant Activity

2.5.3. Protein and Starch Digestibility

2.5.4. Texture and Color Analysis

2.5.5. Sensory Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Black Chickpea Fermentation

3.1.1. Microbiological and Biochemical Characterization

3.1.2. Digestibility and Antinutritional Factors

3.1.3. Antioxidant Activity

3.1.4. Identification of Free and Bound Phenolic Compounds

3.1.5. Quantification of Phenolic Compounds

3.2. Fortified Pasta

3.2.1. Technological Characterization

3.2.2. Nutritional Characterization

3.2.3. Antioxidant Activity

3.2.4 Sensory Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fuad, T.; Prabhasankar, P. Role of Ingredients in Pasta Product Quality: A Review on Recent Developments. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPO. 2019. Available online: https://internationalpasta.org/annual-report/ (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Statista.com. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/40060100/100/pasta/worldwide (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Montalbano, A.; Tesoriere, L.; Diana, P.; Barraja, P.; Carbone, A.; Spano, V.; Parrino, B.; Attanzio, A.; Livrea, M.A.; Cascioferro, S.; et al. Quality characteristics and in vitro digestibility study of barley flour enriched ditalini pasta. LWT 2016, 72, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal, E.-S.M.; Young, J.C.; Rabalski, I. Anthocyanin Composition in Black, Blue, Pink, Purple, and Red Cereal Grains. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4696–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fares, C.; Menga, V. Effects of toasting on the carbohydrate profile and antioxidant properties of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) flour added to durum wheat pasta. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 1140–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, A.; Verni, M.; Montemurro, M.; Coda, R.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Use of fermented quinoa flour for pasta making and evaluation of the technological and nutritional features. LWT 2017, 78, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Verni, M.; Koivula, H.; Montemurro, M.; Seppa, L.; Kemell, M.; Katina, K.; Coda, R.; Gobbetti, M. Influence of fermented faba bean flour on the nutritional, technological and sensory quality of fortified pasta. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schettino, R.; Pontonio, E.; Rizzello, C.G. Use of Fermented Hemp, Chickpea and Milling By-Products to Improve the Nutritional Value of Semolina Pasta. Foods 2019, 8, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schettino, R.; Pontonio, E.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Extension of the Shelf-Life of Fresh Pasta Using Chickpea Flour Fermented with Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroski, M.; de Aguiar, A.C.; Boeing, J.S.; Rotta, E.M.; Wibby, C.L.; Bonafé, E.G.; de Souza, N.E.; Visentainer, J.V. Enhancement of pasta antioxidant activity with oregano and carrot leaf. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.L.G.; Mársico, E.T.; Soares, M.S.; Magalhães, A.O.; Canto, A.C.V.C.S.; Costa-Lima, B.R.C.; Alvares, T.S.; Conte, C.A. Nutritional Profile and Chemical Stability of Pasta Fortified with Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Flour. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sęczyk, Ł.; Świeca, M.; Gawlik-Dziki, U. Effect of carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) flour on the antioxidant potential, nutritional quality, and sensory characteristics of fortified durum wheat pasta. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, S.; Padalino, L.; Costa, C.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Conte, A. Food by-products to fortified pasta: A new approach for optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, M.; Coda, R.; Rizzello, C.G. Recent Advances in the Use of Sourdough Biotechnology in Pasta Making. Foods 2019, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roy, F.; Boye, J.I.; Simpson, B. Bioactive proteins and peptides in pulse crops: Pea, chickpea and lentil. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande, K.; Fabiyi, E. Effect of Processing Methods on Some Antinutritional Factors in Legume Seeds for Poultry Feeding. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2010, 9, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, R.; Katina, K.; Rizzello, C.G. Bran bioprocessing for enhanced functional properties. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 1, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, J.A.; Coda, R.; Centomani, I.; Summo, C.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Exploitation of the nutritional and functional characteristics of traditional Italian legumes: The potential of sourdough fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 196, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Gu, Z.; Han, Y.; Chen, Z. The impact of processing on phytic acid,in vitrosoluble iron and Phy/Fe molar ratio of faba bean (Vicia fabaL.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, I.; Pontonio, E.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Nutritional and functional effects of the lactic acid bacteria fermentation on gelatinized legume flours. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 316, 108426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Calasso, M.; Campanella, D.; De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M. Use of sourdough fermentation and mixture of wheat, chickpea, lentil and bean flours for enhancing the nutritional, texture and sensory characteristics of white bread. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 180, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Polo, A.; Rizzello, C.G. The sourdough fermentation is the powerful process to exploit the potential of legumes, pseudo-cereals and milling by-products in baking industry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2158–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavan, S.; Lotti, C.; Marcotrigiano, A.R.; Mazzeo, R.; Bardaro, N.; Bracuto, V.; Ricciardi, F.; Taranto, F.; D’Agostino, N.; Schiavulli, A.; et al. A Distinct Genetic Cluster in Cultivated Chickpea as Revealed by Genome-wide Marker Discovery and Genotyping. Plant Genome 2017, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mohammadi, K. Nutritional composition of Iranian desi and kabuli chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) cultivars in autumn sowing. Int. J. Agr. Biol. Eng. 2015, 9, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summo, C.; De Angelis, D.; Ricciardi, L.; Caponio, F.; Lotti, C.; Pavan, S.; Pasqualone, A. Nutritional, physico-chemical and functional characterization of a global chickpea collection. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 84, 103306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Lorusso, A.; Montemurro, M.; Gobbetti, M. Use of sourdough made with quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) flour and autochthonous selected lactic acid bacteria for enhancing the nutritional, textural and sensory features of white bread. Food Microbiol. 2016, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACC. Approved methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemistry, 11th ed.; AACC: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, W.; Vogelmeier, C.; Görg, P.D.D.A. Electrophoretic characterization of wheat grain allergens from different cultivars involved in bakers’ asthma. Electrophoresis 1993, 14, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akeson, W.R.; Stahmann, M.A. A Pepsin Pancreatin Digest Index of Protein Quality Evaluation. J. Nutr. 1964, 83, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-Dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Perret, J.; Harris, M.; Wilson, J.; Haley, S.D. Antioxidant Properties of Bran Extracts from “Akron” Wheat Grown at Different Locations. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1566–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuda, H.; Yasumoto, K.; Iwami, K. Antioxidative Action of Indole Compounds during the Autoxidation of Linoleic Acid. Eiyo Shokuryo 2011, 19, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verardo, V.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Marconi, E.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Caboni, M.F. Determination of Free and Bound Phenolic Compounds in Buckwheat Spaghetti by RP-HPLC-ESI-TOF-MS: Effect of Thermal Processing from Farm to Fork. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7700–7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verni, M.; Pontonio, E.; Krona, A.; Jacob, S.; Pinto, D.; Rinaldi, F.; Verardo, V.; Díaz-De-Cerio, E.; Coda, R.; Rizzello, C.G. Bioprocessing of Brewers’ Spent Grain Enhances Its Antioxidant Activity: Characterization of Phenolic Compounds and Bioactive Peptides. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagerman, A.E. (Ed.) Acid buthanol assay for proanthocyanidins. In The Tannin Handbook; Miami University: Oxford, OH, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, R.; Aguirre, A.; Marzo, F. Effects of extrusion and traditional processing methods on antinutrients and in vitro digestibility of protein and starch in faba and kidney beans. Food Chem. 2000, 68, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.-R.; Hsieh, S.-C.; Huang, H.-Y.; Chou, C.-C. Effect of lactic fermentation on the total phenolic, saponin and phytic acid contents as well as anti-colon cancer cell proliferation activity of soymilk. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2013, 115, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, A.; Fongaro, L.; Rossi, M.; Lucisano, M.; Pagani, M.A. Quality characteristics of dried pasta enriched with buckwheat flour. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 2393–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schoenlechner, R.; Drausinger, J.; Ottenschlaeger, V.; Jurackova, K.; Berghofer, E. Functional Properties of Gluten-Free Pasta Produced from Amaranth, Quinoa and Buckwheat. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2010, 65, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’egidio, M.G.; Mariani, B.M.; Nardi, S.; Novaro, P.; Cubadda, R. Chemical and technological variables and their relationships: A predictive equation for pasta cooking quality. Cereal Chem. 1990, 67, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis, M.; Damiano, N.; Rizzello, C.G.; Cassone, A.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M. Sourdough fermentation as a tool for the manufacture of low-glycemic index white wheat bread enriched in dietary fibre. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009, 229, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriles, V.D.; Arêas, J.A.G. Effects of prebiotic inulin-type fructans on structure, quality, sensory acceptance and glycemic response of gluten-free breads. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreerama, Y.N.; Sashikala, V.B.; Pratape, V.M. Variability in the Distribution of Phenolic Compounds in Milled Fractions of Chickpea and Horse Gram: Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8322–8330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekky, R.; Contreras, M.D.M.; El-Gindi, M.R.; Abdel-Monem, A.R.; Abdel-Sattar, E.; Segura-Carretero, A. Profiling of phenolic and other compounds from Egyptian cultivars of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and antioxidant activity: A comparative study. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 17751–17767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pechan, T.; Chang, S.K. Antioxidant and angiotensin-I converting enzyme inhibitory activities of phenolic extracts and fractions derived from three phenolic-rich legume varieties. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 42, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, T.J.; Lee, B.W.; Park, K.H.; Jeong, S.H.; Kim, H.-T.; Ko, J.-M.; Baek, I.-Y.; Lee, J.H. Rapid characterisation and comparison of saponin profiles in the seeds of Korean Leguminous species using ultra performance liquid chromatography with photodiode array detector and electrospray ionisation/mass spectrometry (UPLC–PDA–ESI/MS) analysis. Food Chem. 2014, 146, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Acqua, S.; Uysal, A.; Diuzheva, A.; Gunes, E.; Jekő, J.; Cziáky, Z.; Picot-Allain, C.M.N.; Mahomoodally, M.F. Characterization of phytochemical components of Ferula halophila extracts using HPLC-MS/MS and their pharmacological potentials: A multi-functional insight. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 160, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhao, L.; Qiu, H. Effective extraction of flavonoids from Lycium barbarum L. fruits by deep eutectic solvents-based ultrasound-assisted extraction. Talanta 2019, 203, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, L.; Corfe, B. The role of diet and nutrition on mental health and wellbeing. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 425–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doré, J.; Blottière, H.M. The influence of diet on the gut microbiota and its consequences for health. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minihane, A.M.; Vinoy, S.; Russell, W.R.; Baka, A.; Roche, H.M.; Tuohy, K.M.; Teeling, J.L.; Blaak, E.E.; Fenech, M.; Vauzour, D.; et al. Low-grade inflammation, diet composition and health: Current research evidence and its translation. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verni, M.; De Mastro, G.; De Cillis, F.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Lactic acid bacteria fermentation to exploit the nutritional potential of Mediterranean faba bean local biotypes. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Portincasa, P.; Montemurro, M.; Di Palo, D.M.; Lorusso, M.P.; De Angelis, M.; Bonfrate, L.; Genot, B.; Gobbetti, M. Sourdough Fermented Breads are More Digestible than Those Started with Baker’s Yeast Alone: An In Vivo Challenge Dissecting Distinct Gastrointestinal Responses. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goñi, I.; Valentín-Gamazo, C. Chickpea flour ingredient slows glycemic response to pasta in healthy volunteers. Food Chem. 2003, 81, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, S.S. Intensification of sensory properties of foods for the elderly. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 927S–930S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malunga, L.N.; Bar-El, S.D.; Zinal, E.; Berkovich, Z.; Abbo, S.; Reifen, R.; Dadon, S.B.-E. The potential use of chickpeas in development of infant follow-on formula. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diana, M.; Quílez, J.; Rafecas, M. Gamma-aminobutyric acid as a bioactive compound in foods: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 10, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, C.; Mascarós, A.F.; Barber, C.B. Amino Acid Metabolism by Yeasts and Lactic Acid Bacteria during Bread Dough Fermentation. J. Food Sci. 1992, 57, 1423–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, F.; Champ, M.M.-J. Carbohydrate fractions of legumes: Uses in human nutrition and potential for health. Br. J. Nutr. 2002, 88, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, R.; Kianjam, M.; Pontonio, E.; Verni, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Katina, K.; Rizzello, C.G.; Gobbetti, M. Sourdough-type propagation of faba bean flour: Dynamics of microbial consortia and biochemical implications. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 248, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waters, D.M.; Mauch, A.; Coffey, A.; Arendt, E.K.; Zannini, E. Lactic Acid Bacteria as a Cell Factory for the Delivery of Functional Biomolecules and Ingredients in Cereal-Based Beverages: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 55, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, T.K.; Singh, B.; Sharma, O.P. Microbial degradation of tannins—A current perspective. Biodegradation 1998, 9, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filannino, P.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M. Metabolic and functional paths of lactic acid bacteria in plant foods: Get out of the labyrinth. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Pierson, M. Reduction in antinutritional and toxic components in plant foods by fermentation. Food Res. Int. 1994, 27, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starzyńska-Janiszewska, A.; Stodolak, B. Effect of Inoculated Lactic Acid Fermentation on Antinutritional and Antiradical Properties of Grass Pea (Lathyrus Sativus ‘Krab’) Flour. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 61, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolívar-Monsalve, E.J.; Bolívar-Monsalve, J.; Ceballos-González, C.F.; Ramírez-Toro, C. Reduction in saponin content and production of gluten-free cream soup base using quinoa fermented with Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 42, e13495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarade, K.M.; Singhal, R.S.; Jayram, R.V.; Pandit, A.B. Kinetics of degradation of saponins in soybean flour (Glycine max.) during food processing. J. Food Eng. 2006, 76, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajilata, M.G.; Singhal, R.S.; Kulkarni, P.R. Resistant Starch? A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2006, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verni, M.; Demarinis, C.; Rizzello, C.G.; Baruzzi, F. Design and Characterization of a Novel Fermented Beverage from Lentil Grains. Foods 2020, 9, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verni, M.; Verardo, V.; Rizzello, C.G. How Fermentation Affects the Antioxidant Properties of Cereals and Legumes. Foods 2019, 8, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, Y.-K.; Yao, Y.-Y.; Chang, Y. Characterization of Anthocyanins in Perilla frutescens var. acuta Extract by Advanced UPLC-ESI-IT-TOF-MSn Method and Their Anticancer Bioactivity. Molecules 2015, 20, 9155–9169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hao, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Li, H. Identification of anthocyanins in black rice (Oryza sativa L.) by UPLC/Q-TOF-MS and their in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities. J. Cereal Sci. 2015, 64, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.A.M.; Borges, F.; Guimarães, C.; Lima, J.L.F.C.; Matos, C.; Reis, S. Phenolic Acids and Derivatives: Studies on the Relationship among Structure, Radical Scavenging Activity, and Physicochemical Parameters†. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2122–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; De Paulis, T.; May, J.M. Antioxidant effects of dihydrocaffeic acid in human EA.hy926 endothelial cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2004, 15, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filannino, P.; Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M.; Di Cagno, R. Hydroxycinnamic Acids Used as External Acceptors of Electrons: An Energetic Advantage for Strictly Heterofermentative Lactic Acid Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 7574–7582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perez-Ternero, C.; Macià, A.; De Sotomayor, M.A.; Parrado, J.; Motilva, M.J.; Herrera, M.-D. Bioavailability of the ferulic acid-derived phenolic compounds of a rice bran enzymatic extract and their activity against superoxide production. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2165–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micard, V.; Landazuri, T.; Surget, A.; Moukha, S.; Labat, M.; Rouau, X. Demethylation of Ferulic Acid and Feruloyl-arabinoxylan by Microbial Cell Extracts. LWT 2002, 35, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwajgier, D.; Jakubczyk, A. Biotransformation of ferulic acid by Lactobacillus acidophilus KI and selected Bifidobacterium strains. ACTA Sci. Pol. Technol. Alimen. 2010, 9, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xia, Y.; Li, H.; Shi, X.; Wang, J.; Deng, Z. Bioaccessibility and transformation pathways of phenolic compounds in processed mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion and faecal fermentation. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 60, 103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Products, N.A.A. (Nda) E.P.O.D. Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of a health claim related to cocoa flavanols and maintenance of normal endothelium-dependent vasodilation pursuant to Article 13(5) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres, A.; Frías, J.; Granito, M.; Vidal-Valverde, C. Fermented Pigeon Pea (Cajanus cajan) Ingredients in Pasta Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 6685–6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WP | BC-P | labBC-P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semolina (%) | 77 | 71.7 | 71.7 |

| Black chickpea flour (%) | - | 5.3 | - |

| Fermented black chickpea dough (%) * | - | - | 15 |

| Water (%) | 23 | 23 | 13.3 |

| BC | sBC | labBC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological analysis | |||

| Lactic acid bacteria (Log cfu/g) | 2.54 ± 0.12 c | 7.08 ± 0.16 b | 9.58 ± 0.11 a |

| Yeasts (Log cfu/g) | 2.02 ± 0.09 b | 4.23 ± 0.10 a | 2.15 ± 0.13 b |

| Molds (Log cfu/g) | 2.09 ± 0.11 b | 3.02 ± 0.09 a | 2.33 ± 0.09 b |

| Enterobacteriaceae (Log cfu/g) | 2.27 ± 0.12 b | 4.89 ± 0.14 a | 2.49 ± 0.11 b |

| Biochemical characteristics | |||

| pH | 6.53 ± 0.30 a | 4.76 ± 0.23 b | 3.85 ± 0.19 c |

| Total titratable acidity (mL NaOH 0.1 M) | 2.0 ± 0.1 c | 5.1 ± 0.2 b | 10.2 ± 0.5 a |

| Lactic acid (mmol/kg) | 0.4 ± 0.1 c | 77.0 ± 2.1 b | 123.4 ± 2.5 a |

| Acetic acid (mmol/kg) | 2.14 ± 0.3 c | 18.9 ± 0.5 a | 13.1 ± 0.8 b |

| Total free amino acids (mg/kg) | 1851 ± 21 c | 2249 ± 15 b | 2975 ± 18 a |

| Resistant starch (%) | 1.75 ± 0.11 c | 2.03 ± 0.12 b | 2.81 ± 0.10 a |

| Protein digestibility and Antinutritional factors | |||

| In vitro protein digestibility (%) | 80 ± 1c | 85 ± 1 b | 91 ± 2 a |

| Raffinose (g/kg) | 1.27 ± 0.10 a | 0.84 ± 0.03 b | 0.44 ± 0.02 c |

| Condensed tannins (g/kg) | 0.62 ± 0.02 a | 0.36 ± 0.03 b | 0.34 ± 0.02 b |

| TIA* (U) | 0.66 ± 0.05 a | 0.59 ± 0.05 b | 0.52 ± 0.04 b |

| Total saponins (g/kg) | 0.68 ± 0.02 a | 0.45 ± 0.03 b | 0.29 ± 0.05 c |

| BC | sBC | labBC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free phenolic compounds | |||

| Protocatechuic acid | 3.72 ± 0.19 c | 5.51 ± 0.28 b | 10.57 ± 0.53 a |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside | 2.65 ± 0.13 | nd | nd |

| Dihydrocaffeic acid | nd | 5.98 ± 0.30 b | 93.35 ± 4.67 a |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid hexoside pentoside | 5.70 ± 0.28 c | 8.35 ± 0.37 b | 9.87 ± 0.49 a |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside-pentoside I | 0.36 ± 0.02 b | 0.66 ± 0.03 a | 0.77 ± 0.04 a |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside-pentoside II | 0.99 ± 0.05 b | 1.46 ± 0.07 a | 1.67 ± 0.08 a |

| Phloretic acid | nd | 48.24 ± 2.41 b | 102.00 ± 5.10 a |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid hexoside-pentoside dehydrodimer | 2.56 ± 0.13 c | 3.87 ± 0.18 b | 4.49 ± 0.22 a |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid hexoside-pentoside trimer | 0.36 ± 0.02 c | 0.59 ± 0.03 b | 0.70 ± 0.03 a |

| Hydroxibenzoic acid derivative | 0.56 ± 0.03 b | 1.44 ± 0.07 a | 1.52 ± 0.08 a |

| Myricetin derivative | 1.06 ± 0.05 c | 1.40 ± 0.07 b | 1.71 ± 0.09 a |

| Quercetin-3,7-O-di-glucopyranoside | 0.76 ± 0.04 a | 0.30 ± 0.04 b | 0.29 ± 0.05 b |

| Quercetin-3-O-b-D-xylopyranosyl-(1/2)-rutinoside | 1.44 ± 0.07 c | 1.66 ± 0.09 b | 2.03 ± 0.10 a |

| Myricetin-O-methylether hexoside-deoxyhexoside-pentoside | 3.63 ± 0.18 c | 4.87 ± 0.24 b | 5.25 ± 0.26 a |

| Kaempferol 3-O-lathyroside-7-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside | 1.43 ± 0.07 c | 1.87 ± 0.09 a | 2.01 ± 0.10 a |

| Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside-7-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside | 1.46 ± 0.05 a | 1.03 ± 0.07 b | 0.98 ± 0.07 b |

| Total | 26.67 ± 1.09 c | 87.22 ± 2.97 b | 237.02 ± 10.95 a |

| Bound phenolic compounds | |||

| Gallic acid | 9.66 ± 0.48 a | 7.29 ± 0.36 b | 8.48 ± 0.42 a |

| Protocatechuic acid | 29.31 ± 1.47 a | 18.88 ± 0.94 c | 25.32 ± 1.27 b |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside | 2.24 ± 0.11 a | 0.34 ± 0.02 b | 0.32 ± 0.02 b |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid hexoside-pentoside | 1.34 ± 0.07 a | 0.76 ± 0.04 c | 1.12 ± 0.06 b |

| Morin | 1.43 ± 0.07 | 1.44 ± 0.07 | 1.62 ± 0.10 |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside-pentoside I | 0.41 ± 0.02 a | 0.34 ± 0.01 b | 0.33 ± 0.01 b |

| Ferulic acid | 7.63 ± 0.38 a | 4.35 ± 0.22 b | 4.47 ± 0.22 b |

| Isoferulic acid | 19.73 ± 0.99 a | 13.96 ± 0.70 c | 15.97 ± 0.80 b |

| Myricetin-O-methyl ether hexoside-deoxyhexoside-pentoside | 0.71 ± 0.04 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 0.16 ± 0.01 b |

| Kaempferol 3-O-lathyroside-7-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside | 0.62 ± 0.03 a | 0.19 ± 0.02 b | 0.19 ± 0.02 b |

| Total | 73.09 ± 2.94 a | 47.54 ± 2.12 c | 57.88 ± 3.05 b |

| WP | BC-P | labBC-P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical and nutritional characteristics | |||

| pH | 6.47 ± 0.02 b | 6.91 ± 0.01 a | 5.97 ± 0.02 c |

| Moisture (%) | 8.9 ± 0.2 | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 9.2 ± 0.1 |

| Proteins (% of d.m.) | 12.6 ± 0.2 b | 13.7 ± 0.2 a | 13.6 ± 0.2 a |

| Fat (% of d.m.) | 2.0 ± 0.1 b | 2.2 ± 0.2 a | 2.2 ± 0.2 a |

| Available carbohydrates (% of d.m.) | 79.0 ± 1.2 a | 77.1 ± 1.5 a b | 75.9 ± 0.8 b |

| Dietary fibers (% of d.m.) | 4.0 ± 0.1 b | 5.2 ± 0.2 a | 5.4 ± 0.1 a |

| Ash (% of d.m.) | 0.84 ± 0.04 b | 0.95 ± 0.02 a | 1.01 ± 0.02 a |

| Total Free Amino Acids (mg/kg) | 152 ± 4 c | 429 ± 6 b | 602 ± 11 a |

| Hydrolysis Index (%) * | 73 ± 2 a | 70 ± 1 a | 60 ± 2 b |

| In Vitro Protein Digestibility (%) * | 45 ± 1 c | 65 ± 2 b | 73 ± 2 a |

| Technological and textural* characteristics | |||

| Optimal Cooking Time (min) | 9.7 ± 0.2 a | 6.9 ± 0.2 b | 6.3 ± 0.1 c |

| Water absorption (g/100 g) | 128.6 ± 1.2 a | 113.1 ± 1.5 b | 115.3 ±1.5 b |

| Cooking loss (g/100 g) | 4.70 ± 0.12 b | 5.73 ± 0.14 a | 5.80 ± 0.08 a |

| Hardness (N) | 4.31 ± 0.11 b | 4.89 ± 0.09 a | 4.80 ± 0.05 a |

| Resilience | 0.68 ± 0.04 a | 0.58 ± 0.05 b | 0.58 ± 0.02 b |

| Chewiness (N) | 2.86 ± 0.05 a | 2.56 ± 0.03 b | 2.53 ± 0.03 b |

| Cohesiveness | 0.59 ± 0.02 a | 0.44 ± 0.02 b | 0.49 ± 0.03 b |

| Color analysis* | |||

| L | 66.42 ± 0.20 a | 44.18 ± 0.18 b | 46.57 ± 0.21 b |

| a | −6.95 ± 0.05 b | −7.14 ± 0.08 c | −1.67 ± 0.03 a |

| b | 20.61 ± 0.03 a | 14.16 ± 0.05 b | 12.78 ± 0.04 c |

| ΔE | 16.79 c | 22.56 a | 20.57 b |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Pasquale, I.; Verni, M.; Verardo, V.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Rizzello, C.G. Nutritional and Functional Advantages of the Use of Fermented Black Chickpea Flour for Semolina-Pasta Fortification. Foods 2021, 10, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010182

De Pasquale I, Verni M, Verardo V, Gómez-Caravaca AM, Rizzello CG. Nutritional and Functional Advantages of the Use of Fermented Black Chickpea Flour for Semolina-Pasta Fortification. Foods. 2021; 10(1):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010182

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Pasquale, Ilaria, Michela Verni, Vito Verardo, Ana María Gómez-Caravaca, and Carlo Giuseppe Rizzello. 2021. "Nutritional and Functional Advantages of the Use of Fermented Black Chickpea Flour for Semolina-Pasta Fortification" Foods 10, no. 1: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010182

APA StyleDe Pasquale, I., Verni, M., Verardo, V., Gómez-Caravaca, A. M., & Rizzello, C. G. (2021). Nutritional and Functional Advantages of the Use of Fermented Black Chickpea Flour for Semolina-Pasta Fortification. Foods, 10(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010182