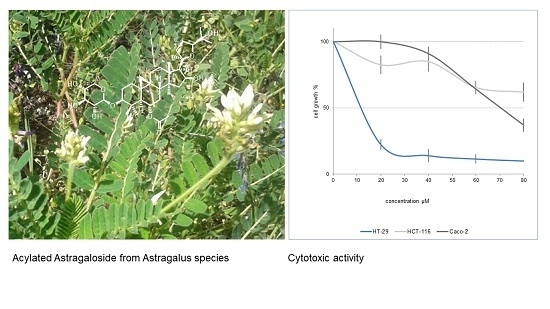

Spectroscopic Characterization and Cytotoxicity Assessment towards Human Colon Cancer Cell Lines of Acylated Cycloartane Glycosides from Astragalus boeticus L.

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structural Elucidation of Cycloartane Glycosides from Astragalus boeticus L.

2.2. Cytotoxicity of Cycloartane Glycosides from Astragalus boeticus Against Human Colorectal Cancer Cells

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

3.2. GC–MS Analysis of the Sugar Moieties

3.3. Determination of Absolute Configuration of Monosaccharides of Compound 1 and 5

3.4. Plant Material

3.5. Extraction and Isolation of Compound 1–5

3.6. Cell Lines

3.7. Proliferation Assay

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verotta, L.; El-Sebakhy, N. Cycloartane and oleanane saponins from Astragalus sp. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 179–234. [Google Scholar]

- Prohens, J.; Andújar, I.; Vilanova, S.; Plazas, M.; Gramazio, P.; Prohens, R.; Herraiz, F.J.; De Ron, A.M. Swedish coffee (Astragalus boeticus L.), a neglected coffee substitute with a past and a potential future. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2013, 61, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.C.; Davis, A.M. Nitro Compounds in Introduced Astragalus Species. J. Range Manage. 1982, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Ralphs, M.H.; Welch, K.D.; Stegelmeier, B.L. Locoweed Poisoning in Livestock. Rangelands 2009, 31, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionkova, I.; Shkondrov, A.; Krasteva, I.; Ionkov, T. Recent progress in phytochemistry, pharmacology and biotechnology of Astragalus saponins. Phytochem. Rev. 2014, 13, 343–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, J.L.; Waterman, P.G. A review of the pharmacology and toxicology of Astragalus. Phytother. Res. 1997, 11, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülcemal, D.; Aslanipour, B.; Bedir, E. Secondary Metabolites from Turkish Astragalus Species. In Plant and Human Health, Volume 2: Phytochemistry and Molecular Aspects; Ozturk, M., Hakeem, K.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 43–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Auyeung, K.K.; Zhang, X.; Ko, J.K. Astragalus saponins modulates colon cancer development by regulating calpain-mediated glucose-regulated protein expression. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.P.; Shen, J.G.; Xu, W.C.; Li, J.; Jiang, J.Q. Secondary metabolites of the genus Astragalus: Structure and biological-activity update. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 1004–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkondrov, A.; Krasteva, I.; Bucar, F.; Kunert, O.; Kondeva-Burdina, M.; Ionkova, I. A new tetracyclic saponin from Astragalus glycyphyllos L. and its neuroprotective and hMAO-B inhibiting activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistelli, L.; Bertoli, A.; Lepori, E.; Morelli, I.; Panizzi, L. Antimicrobial and antifungal activity of crude extracts and isolated saponins from Astragalus verrucosus. Fitoterapia 2002, 73, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, P.; Shen, J.; Qiu, J.; Wu, H.; Zhu, X. The antioxidative effects of astragalus saponin I protect against development of early diabetic nephropathy. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2006, 101, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanipour, B.; Gulcemal, D.; Nalbantsoy, A.; Yusufoglu, H.; Bedir, E. Secondary metabolites from Astragalus karjaginii BORISS and the evaluation of their effects on cytokine release and hemolysis. Fitoterapia 2017, 122, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auyeung, K.K.; Law, P.C.; Ko, J.K. Combined therapeutic effects of vinblastine and Astragalus saponins in human colon cancer cells and tumor xenograft via inhibition of tumor growth and proangiogenic factors. Nutr. Cancer 2014, 66, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debelec-Butuner, B.; Ozturk, M.B.; Tag, O.; Akgun, I.H.; Yetik-Anacak, G.; Bedir, E.; Korkmaz, K.S. Cycloartane-type sapogenol derivatives inhibit NFkappaB activation as chemopreventive strategy for inflammation-induced prostate carcinogenesis. Steroids 2018, 135, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auyeung, K.K.; Han, Q.B.; Ko, J.K. Astragalus membranaceus: A Review of its Protection Against Inflammation and Gastrointestinal Cancers. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2016, 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, V.; Scognamiglio, M.; Belli, V.; Esposito, A.; D’Abrosca, B.; Chambery, A.; Russo, R.; Panella, M.; Russo, A.; Ciardiello, F.; et al. Metabolomic approach for a rapid identification of natural products with cytotoxic activity against human colorectal cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malvezzi, M.; Carioli, G.; Bertuccio, P.; Rosso, T.; Boffetta, P.; Levi, F.; La Vecchia, C.; Negri, E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2016 with focus on leukaemias. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baselga, J. The EGFR as a target for anticancer therapy - focus on cetuximab. Eur. J. Cancer 2001, 37, S16–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardiello, F.; Tortora, G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1160–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scognamiglio, M.; D’Abrosca, B.; Fiumano, V.; Chambery, A.; Severino, V.; Tsafantakis, N.; Pacifico, S.; Esposito, A.; Fiorentino, A. Oleanane saponins from Bellis sylvestris Cyr. and evaluation of their phytotoxicity on Aegilops geniculata Roth. Phytochemistry 2012, 84, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.B.; Zhai, Y.D.; Ma, Z.P.; Yang, C.J.; Pan, R.; Yu, J.L.; Wang, Q.H.; Yang, B.Y.; Kuang, H.X. Triterpenoids and Flavonoids from the Leaves of Astragalus membranaceus and Their Inhibitory Effects on Nitric Oxide Production. Chem. Biodivers. 2015, 12, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, I.; Wang, H.; Saito, M.; Takagi, A.; Yoshikawa, M. Saponin and sapogenol. XXXV. Chemical constituents of astragali radix, the root of Astragalus membranaceus Bunge. (2). Astragalosides I, II and IV, acetylastragaloside I and isoastragalosides I and II. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1983, 31, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tin, M.M.; Cho, C.H.; Chan, K.; James, A.E.; Ko, J.K. Astragalus saponins induce growth inhibition and apoptosis in human colon cancer cells and tumor xenograft. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auyeung, K.K.; Cho, C.H.; Ko, J.K. A novel anticancer effect of Astragalus saponins: Transcriptional activation of NSAID-activated gene. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 1082–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionkova, I.; Momekov, G.; Proksch, P. Effects of cycloartane saponins from hairy roots of Astragalus membranaceus Bge., on human tumor cell targets. Fitoterapia 2010, 81, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auyeung, K.K.; Woo, P.K.; Law, P.C.; Ko, J.K. Astragalus saponins modulate cell invasiveness and angiogenesis in human gastric adenocarcinoma cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saif, M.W. Colorectal cancer in review: The role of the EGFR pathway. Expert Opin Investig. Drugs 2010, 19, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veluchamy, J.P.; Spanholtz, J.; Tordoir, M.; Thijssen, V.L.; Heideman, D.A.; Verheul, H.M.; de Gruijl, T.D.; van der Vliet, H.J. Combination of NK Cells and Cetuximab to Enhance Anti-Tumor Responses in RAS Mutant Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richman, S.D.; Seymour, M.T.; Chambers, P.; Elliott, F.; Daly, C.L.; Meade, A.M.; Taylor, G.; Barrett, J.H.; Quirke, P. KRAS and BRAF Mutations in Advanced Colorectal Cancer Are Associated With Poor Prognosis but Do Not Preclude Benefit From Oxaliplatin or Irinotecan: Results From the MRC FOCUS Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5931–5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.D.; Tejpar, S.; Delorenzi, M.; Yan, P.; Fiocca, R.; Klingbiel, D.; Dietrich, D.; Biesmans, B.; Bodoky, G.; Barone, C.; et al. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: Results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Kohne, C.H.; Lang, I.; Folprecht, G.; Nowacki, M.P.; Cascinu, S.; Shchepotin, I.; Maurel, J.; Cunningham, D.; Tejpar, S.; et al. Cetuximab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: Updated analysis of overall survival according to tumor KRAS and BRAF mutation status. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2011–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, P.B.; Hauschild, A.; Robert, C.; Haanen, J.B.; Ascierto, P.; Larkin, J.; Dummer, R.; Garbe, C.; Testori, A.; Maio, M.; et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2507–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopetz, S.; Desai, J.; Chan, E.; Hecht, J.R.; O’Dwyer, P.J.; Lee, R.J.; Nolop, K.B.; Saltz, L. PLX4032 in metastatic colorectal cancer patients with mutant BRAF tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahallad, A.; Sun, C.; Huang, S.D.; Di Nicolantonio, F.; Salazar, R.; Zecchin, D.; Beijersbergen, R.L.; Bardelli, A.; Bernards, R. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature 2012, 483, 100–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scognamiglio, M.; Fiumano, V.; D’Abrosca, B.; Esposito, A.; Choi, Y.H.; Verpoorte, R.; Fiorentino, A. Chemical interactions between plants in Mediterranean vegetation: The influence of selected plant extracts on Aegilops geniculata metabolome. Phytochemistry 2014, 106, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors. |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δC | Type | δH (J in Hz) | HMBCa | δC, | Type | δH (J in Hz) | HMBC a | δC, | Type | δH (J in Hz) | HMBC a |

| 1 | 32.8 | CH2 | 1.85 s 1.67 s | 2, 10 2, 10 | 32.3 | CH2 | 1.84 s 1.65 s | 2, 10 2, 10 | 32.8 | CH2 | 1.29 s | |

| 2 | 30.3 | CH2 | 1.98 ov 1.64 ov | 3, 4 3, 4 | 30.0 | CH2 | 1.88 ov 1.69 ov | 3, 4 3, 4 | 30.2 | CH2 | 1.99 ov | 3, 4 |

| 3 | 89.1 | CH | 3.21 d (J = 1.8) | 28, 29, 1xyl | 89.1 | CH | 3.29 ov | 28, 29, 1xyl | 89.1 | CH | 3.21 ov | 1xyl |

| 4 | 42.8 | C | 42.0 | C | 42.8 | C | ||||||

| 5 | 51.2 | CH | 1.71 s | 1, 4, 7, 10, 28, 29 | 53.9 | CH | 1.38 s | 1, 4, 7, 10, 28, 29 | 51.3 | CH | 1.72 s | 1, 4, 7, 10, 28, 29 |

| 6 | 72.0 | CH | 4.75 ov | 4, 5, 7, 8, 1Ac | 68.5 | CH | 3.48 ov | 4, 5, 7, 8 | 72.1 | CH | 4.75 ov | 4, 5, 1ac |

| 7 | 34.0 | CH2 | 1.56 ov | 5, 6 | 33.4 | CH2 | 1.46 ov | 5, 6 | 34.1 | CH2 | 1.57 | 5, 6, 8, 9, 14 |

| 8 | 46.7 | CH | 1.95 s | 6, 9, 10, 13, 14, 19, 30 | 48.0 | CH | 1.46 s | 6, 9, 10, 13, 14, 19, 30 | 46.1 | CH | 1.94 s | 6, 10, 13, 14, 15, 19 |

| 9 | 21.8 | C | 21.4 | C | 21.6 | C | ||||||

| 10 | 29.6 | C | 29.2 | C | 29.2 | C | ||||||

| 11 | 26.8 | CH2 | 1.97 m | 8, 12, 19 | 26.4 | CH2 | 1.97 s | 8, 12, 19 | 26.4 | CH2 | 1.97 s | 12 |

| 12 | 34.1 | CH2 | 1.64 ov 1.56 ov | 14, 18 14, 18 | 33.4 | CH2 | 1.54 ov 1.37 ov | 14, 18 14, 18 | 34.1 | CH2 | 1.64 ov 1.56 ov | |

| 13 | 47.0 | C | 44.7 | C | 46.9 | C | ||||||

| 14 | 46.4 | C | 47.0 | C | 46.6 | C | ||||||

| 15 | 46.2 | CH2 | 1.87 d (J = 8.0) 1.39 d (J = 8.0) | 8, 13, 17, 30 8, 13, 17, 30 | 46.4 | CH2 | 1.98 d (J = 4.4) 1.32 d (J = 6.8) | 8, 13, 17, 30 8, 13, 17, 30 | 46.0 | CH2 | 1.86 d (J = 6.0) 1.42 d (J = 6.4) | 8, 13, 14, 17, 30 13, 14, 30 |

| 16 | 74.5 | CH | 4.65 m | 13, 14, 15 | 73.9 | CH | 4.64 m | 13, 14, 15 | 74.3 | CH | 4.65 m | 13, 14, 15 |

| 17 | 58.9 | CH | 2.37 d (J = 7.8) | 13, 14, 16, 20, 21, 22 | 58.2 | CH | 2.37 d (J = 7.7) | 13, 14, 16, 20, 21, 22 | 58.7 | CH | 2.38 d (J=8.0) | 13, 14, 16, 20, 21, 22 |

| 18 | 21.4 | CH3 | 1.27 s | 12, 15, 17 | 21.4 | CH3 | 1.23 s | 12, 15, 17 | 21.7 | CH3 | 1.27 s | 12, 15, 17 |

| 19 | 30.1 | CH2 | 0.61 s 0.40 s | 1, 5, 8, 9, 10 1, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11 | 31.4 | CH2 | 0.53 s 0.37 s | 1, 5, 8, 9, 10 1, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11 | 30.2 | CH2 | 0.61 s 0.40 s | 1, 5, 8, 9, 10,11 1, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11 |

| 20 | 88.3 | C | - | 88.2 | C | - | 88.3 | C | - | |||

| 21 | 28.4 | CH3 | 1.22 s | 17, 20, 22 | 28.1 | CH3 | 1.25 s | 17, 20, 22 | 28.0 | CH3 | 1.24 s | |

| 22 | 35.5 | CH2 | 2.62 ov 1.87 ov | 17, 20, 21 17, 20, 21 | 34.9 | CH2 | 1.69 ov | 17, 20, 21 17, 20, 21 | 35.6 | CH2 | 2.54 ov 1.84 | 17 17 |

| 23 | 26.8 | CH2 | 2.02 ov 1.73 | 20, 24, 25 17, 24, 25 | 26.4 | CH2 | 2.02 ov | 20, 24, 25 17, 24, 25 | 26.8 | CH2 | 2.16 ov 1.72 | 24, 25 24, 25 |

| 24 | 82.6 | CH | 3.76 m | 25 | 81.4 | CH | 3.80 m | 25 | 83.0 | CH | 3.82 m | 1glc |

| 25 | 71.2 | C | - | 71.2 | C | - | 79.9 | C | - | |||

| 26 | 26.6 | CH3 | 1.13 s | 17, 24, 25 | 26.5 | CH3 | 1.15 s | 17, 24, 25 | 23.2 | CH3 | 1.22 s | 20, 23, 24, 25 |

| 27 | 27.6 | CH3 | 1.26 s | 24, 25, 26 | 27.1 | CH3 | 1.24 s | 24, 25, 26 | 25.3 | CH3 | 1.38 s | 23, 24, 26 |

| 28 | 27.2 | CH3 | 1.05 s | 3, 4, 5, 29 | 16.1 | CH3 | 0.98 s | 3, 4, 5, 29 | 16.5 | CH3 | 0.98 s | 3, 4, 5, 28 |

| 29 | 16.6 | CH3 | 0.98 s | 3, 4, 5, 28 | 27.1 | CH3 | 1.25 s | 3, 4, 5, 28 | 27.3 | CH3 | 1.04 s | 3, 4, 5, 29 |

| 30 | 20.3 | CH3 | 1.01 s | 9, 14, 15 | 20.9 | CH3 | 0.96 s | 9, 14, 15 | 20.2 | CH3 | 0.99 s | 14, 15 |

| 1xyl | 105.9 | CH | 4.32 d (J = 7.4) | 3, 5xyl | 105.9 | CH | 4.43 d (J = 7.4) | 3, 5xyl | 107.4 | CH | 4.26 d (J = 7.0) | 3 |

| 2xyl | 75.4 | CH | 3.26 ov | 4xyl | 75.4 | CH | 3.26 ov | 4xyl | 75.5 | CH | 3.19 ov | |

| 3xyl | 75.2 | CH | 3.57 ov | 4xyl, 5xyl | 75.2 | CH | 3.57 ov | 4xyl, 5xyl | 78.0 | CH | 3.29 ov | |

| 4xyl | 73.6 | CH | 4.72 m | 2xyl, 3xyl, 5xyl, 2mal | 73.6 | CH | 4.72 m | 2xyl, 3xyl, 5xyl, 2mal | 71.2 | CH | 3.46 m | |

| 5xyl | 63.3 | CH2 | 3.28 ov 3.96 ov | 1xyl, 3xyl, 4xyl 1xyl, 3xyl, 4xyl | 63.3 | CH2 | 3.28 ov 3.96 ov | 1xyl, 3xyl, 4xyl 1xyl, 3xyl, 4xyl | 66.7 | CH2 | 3.18 ov 3.82 ov | |

| 1glc | - | - | - | - | - | 99.6 | CH | 4.51 d (J = 6.6) | 25 | |||

| 2glc | - | - | - | - | - | 75.0 | CH | 3.18 ov | 5glc | |||

| 3glc | - | - | - | - | - | 78.2 | CH | 3.32 ov | 1glc, 5glc | |||

| 4glc | - | - | - | - | - | 71.2 | CH | 3.31 ov | 6glc | |||

| 5glc | - | - | - | - | - | 77.5 | CH | 3.24 ov | 1glc, 3glc | |||

| 6glc | - | - | - | - | - | 62.7 | CH2 | 3.65 ov 3.79 ov | 4glc 4glc | |||

| 1ac | 172.2 | C | - | - | - | 172.2 | C | |||||

| 2ac | 22.2 | CH3 | 1.99 s | 1ac | - | - | 21.8 | CH3 | 1.99 s | 1ac | ||

| 1mal | 170.6 | C | - | 170.6 | C | - | - | - | ||||

| 2 mal | 51.8 | CH2 | 3.69 s | 1mal, 3mal | 51.8 | CH2 | 3.69 s | 1mal, 3mal | - | - | ||

| 3 mal | 171.7 | C | - | 171.7 | C | - | - | - | ||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Graziani, V.; Esposito, A.; Scognamiglio, M.; Chambery, A.; Russo, R.; Ciardiello, F.; Troiani, T.; Potenza, N.; Fiorentino, A.; D’Abrosca, B. Spectroscopic Characterization and Cytotoxicity Assessment towards Human Colon Cancer Cell Lines of Acylated Cycloartane Glycosides from Astragalus boeticus L. Molecules 2019, 24, 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24091725

Graziani V, Esposito A, Scognamiglio M, Chambery A, Russo R, Ciardiello F, Troiani T, Potenza N, Fiorentino A, D’Abrosca B. Spectroscopic Characterization and Cytotoxicity Assessment towards Human Colon Cancer Cell Lines of Acylated Cycloartane Glycosides from Astragalus boeticus L. Molecules. 2019; 24(9):1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24091725

Chicago/Turabian StyleGraziani, Vittoria, Assunta Esposito, Monica Scognamiglio, Angela Chambery, Rosita Russo, Fortunato Ciardiello, Teresa Troiani, Nicoletta Potenza, Antonio Fiorentino, and Brigida D’Abrosca. 2019. "Spectroscopic Characterization and Cytotoxicity Assessment towards Human Colon Cancer Cell Lines of Acylated Cycloartane Glycosides from Astragalus boeticus L." Molecules 24, no. 9: 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24091725

APA StyleGraziani, V., Esposito, A., Scognamiglio, M., Chambery, A., Russo, R., Ciardiello, F., Troiani, T., Potenza, N., Fiorentino, A., & D’Abrosca, B. (2019). Spectroscopic Characterization and Cytotoxicity Assessment towards Human Colon Cancer Cell Lines of Acylated Cycloartane Glycosides from Astragalus boeticus L. Molecules, 24(9), 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24091725