Optimization of Influential Nutrients during Direct Cellulose Fermentation into Hydrogen by Clostridium thermocellum

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

| Composition | Cellulose (A) | YE (B) | Mg (C) | H2 | Ethanol (mmol/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g/L | mmol/L | mol/(mol hexose) | mmol/(g·cell·h) | ||||

| 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 17.83 | 1.22 | 5.09 | 10.8 |

| 2 | 50 | 1 | 1 | 12.71 | 1.19 | 4.05 | 8.8 |

| 3 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 18.90 | 1.17 | 5.49 | 12.71 |

| 4 | 50 | 2 | 1 | 15.34 | 1.14 | 3.91 | 10.86 |

| 5 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 31.84 | 1.04 | 6.46 | 33.21 |

| 6 | 50 | 1 | 2 | 23.40 | 0.98 | 4.46 | 24.92 |

| 7 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 46.22 | 1.11 | 6.67 | 50.4 |

| 8 | 50 | 2 | 2 | 43.40 | 1.02 | 5.03 | 45.17 |

| 9 | 10 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 41.79 | 1.22 | 6.59 | 35.6 |

| 10 | 50 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 42.50 | 1.17 | 5.86 | 39.74 |

| 11 | 30 | 1 | 1.5 | 33.77 | 1.29 | 6.34 | 26.9 |

| 12 | 30 | 2 | 1.5 | 50.77 | 1.27 | 5.68 | 39.8 |

| 13 | 30 | 1.5 | 1 | 22.50 | 1.15 | 4.26 | 17.1 |

| 14 | 30 | 1.5 | 2 | 43.80 | 1.05 | 5.25 | 45.3 |

| Centre point | 30 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 51.60 | 1.29 | 6.79 | 37.06 |

| 30 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 47.47 | 1.25 | 6.61 | 40.82 | |

| 30 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 48.90 | 1.24 | 6.62 | 41.9 | |

| Run No. | Acetate | Formate | Lactate | Cell Growth (mg·protein/L) | Redox (O/R) | Substrate Utilization (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mmol/L | ||||||

| 1 | 10.65 | 1.89 | 3.86 | 177 | 1.11 | 23.82 |

| 2 | 6.98 | 2.33 | 1.96 | 163 | 1.16 | 3.20 |

| 3 | 11.94 | 3.16 | 3.79 | 181 | 1.14 | 23.65 |

| 4 | 9.1 | 3.93 | 2.36 | 210 | 1.19 | 4.17 |

| 5 | 18.3 | 3.36 | 3.91 | 270 | 1.10 | 50.85 |

| 6 | 13.84 | 3.36 | 2.56 | 289 | 1.12 | 7.69 |

| 7 | 22.22 | 5.35 | 1.96 | 338 | 1.19 | 65.52 |

| 8 | 24.1 | 5.68 | 4.95 | 492 | 1.17 | 13.71 |

| 9 | 21.04 | 3.19 | 3.98 | 355 | 1.14 | 55.76 |

| 10 | 22.65 | 1.97 | 1.47 | 409 | 1.21 | 10.59 |

| 11 | 15.37 | 3.04 | 2.80 | 294 | 1.18 | 12.05 |

| 12 | 25.43 | 2.00 | 3.34 | 510 | 1.27 | 22.25 |

| 13 | 11.16 | 3.44 | 4.30 | 291 | 1.20 | 8.61 |

| 14 | 24.34 | 6.44 | 3.39 | 475 | 1.24 | 23.07 |

| Centre points | 27.81 | 6.32 | 5.54 | 378 | 1.19 | 23.46 |

| 23.49 | 5.18 | 2.62 | 405 | 1.23 | 21.67 | |

| 25.94 | 5.27 | 1.95 | 417 | 1.21 | 22.49 | |

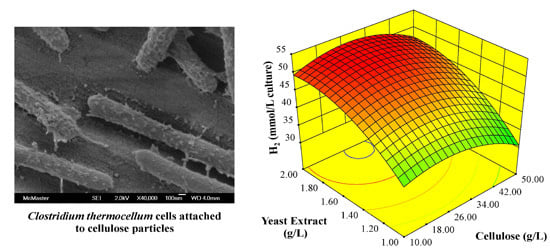

2.1. Modeling and Subsequent Optimization

2.2. Concentration of H2

| Source | Co-Efficient | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | – | 44.53 | <0.0001 |

| Intercept | 47.68 | – | – |

| A: cellulose | −1.92 | 4.51 | 0.0665 |

| B: YE | 5.51 | 36.97 | 0.0003 |

| C: Mg | 10.14 | 125.25 | <0.0001 |

| AB | 0.9 | 0.79 | 0.4014 |

| BC | 3.84 | 14.34 | 0.0053 |

| A2 | −4.3 | 6.05 | 0.0393 |

| B2 | −4.18 | 5.7 | 0.044 |

| C2 | −13.3 | 57.75 | <0.0001 |

| Lack of Fit | – | 2.15 | 0.3506 |

2.3. Substrate Specific Yield and Specific Productivity of H2

| Source | Co-Efficient | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | – | 22.95 | 0.0002 |

| Intercept | 1.26 | – | – |

| A: cellulose | −0.026 | 8.18 | 0.0244 |

| B: YE | −0.0086 | 0.91 | 0.3715 |

| C: Mg | −0.067 | 55.17 | 0.0001 |

| AB | −0.0041 | 0.16 | 0.6981 |

| AC | −0.011 | 1.27 | 0.2976 |

| BC | 0.028 | 7.48 | 0.0291 |

| A2 | −0.06 | 11.97 | 0.0106 |

| B2 | 0.064 | 13.23 | 0.0083 |

| C2 | −0.15 | 76.11 | <0.0001 |

| Lack of Fit | – | 1.07 | 0.5478 |

| Source | Co-Efficient | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | – | 24.97 | <0.0001 |

| Intercept | 6.36 | – | – |

| A: cellulose | −0.72 | 36.38 | <0.0001 |

| B: YE | 0.018 | 0.024 | 0.8807 |

| C: Mg | 0.49 | 16.68 | 0.0015 |

| C2 | −1.27 | 46.79 | <0.0001 |

| Lack of Fit | – | 16.75 | 0.058 |

2.4. A Balanced Optimum through Desirability

| Predictor/Response Variable | Goal | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Importance | Best Solution | Desirability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose (g/L) | Within range | 10 | 50 | 3 | 25.33 | 0.95 |

| Yeast extract (g/L) | Within range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1.94 | 0.95 |

| Magnesium chloride (g/L) | Within range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1.75 | 0.95 |

| Concentration (mmol H2/L culture) | Maximize | 12.71 | 55 | 5 | 52.82 | 0.95 |

| Substrate specific yield (mol H2/mol glucose) | Within range | 0.98 | 1.31 | 3 | 1.24 | 0.95 |

| Specific productivity (mmol H2/(g·protein·h) | Within range | 3.91 | 6.79 | 3 | 6.4 | 0.95 |

2.5. Ethanol: The Major Competing End-Product

2.5.1. Ethanol Concentration Model

| Source | Co-Efficient | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | – | 73.19 | <0.0001 |

| Intercept | 39.16 | – | – |

| A: cellulose | −1.32 | 2.94 | 0.1203 |

| B: YE | 5.43 | 49.61 | <0.0001 |

| C: Mg | 13.87 | 323.71 | <0.0001 |

| AC | −1.21 | 1.97 | 0.1944 |

| BC | 4.18 | 23.55 | 0.0009 |

| B2 | −6.16 | 19.32 | 0.0017 |

| C2 | −8.31 | 35.17 | 0.0002 |

| Lack of Fit | – | 0.9 | 0.620 |

2.5.2. Stationary Point Estimation

2.6. The Acetyl-CoA Branch Point

2.7. Influence of Nutrients

2.8. Verification of Overall Optimum for H2 Production (OptH)

| Predicted vs. Actual | Concentration (mmol/L) | Specific rate (mmol/(g·cell·h)) | Yield (mol/mol hexose) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction | 52.82 | 6.4 | 1.24 |

| Experimental | 57.28 ± 4.8 | 7.48 ± 1.2 | 1.30 ± 0.05 |

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Microorganism and Growth Medium

3.2. Experimental Set-up

3.3. Experimental Design and Optimization

3.4. Factor Coding

| Factors | Unit | Actual Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coded Levels | Low (−1) | Centre (0) | High (1) | |

| A: α-Cellulose | g/L | 10 | 30 | 50 |

| B: YE | g/L | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

| C: Mg | g/L | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

3.5. Statistical Modeling

3.6. Desirability Function

3.7. Analysis of End-Products and Growth

3.8. Estimation of Product Yields and Redox Balance

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Show, K.Y.; Lee, D.J.; Tay, J.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Chang, J.S. Biohydrogen production: Current perspectives and the way forward. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2012, 37, 15616–15631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynd, L.R.; Zyl, W.H.V.; Mcbride, J.E.; Laser, M. Consolidated bioprocessing of cellulosic biomass: An update. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005, 16, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, B.G.; Chinn, M.S. Consolidated bioprocessing of lignocellulosic feedstocks for ethanol fuel production. BioEnergy Res. 2013, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogsett, D.A.; Ahn, H.J.; Bernardez, T.D.; South, C.R.; Lynd, L.R. Direct microbial conversion: Prospects, progress, and obstacles. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1992, 34, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.G.; McBride, J.E.; Joe, S.A.; Lynd, L.R. Recent progress in consolidated bioprocessing. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhgren, K.; Rudolf, A.; Galbe, M.; Larsson, S. Fuel ethanol production from steam pretreated corn stover using SSF at high dry matter concentration. Biomass Bioenergy 2006, 30, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, B.H. Optimization of Ethanol Production from Concentrated Substrate. Ph.D. Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA, 4 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lynd, L.R.; Weimer, P.J.; van Zyl, W.H.; Pretorius, I.S. Microbial cellulose utilization: Fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66, 506–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, R.; Cicek, N.; Sparling, R.; Levin, D.B. Influence of initial cellulose concentration on the carbon flow distribution during batch fermentation of cellulose by Clostridium thermocellum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 82, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, R.; Cicek, N.; Sparling, R.; Levin, D.B. Effect of substrate loading on hydrogen production during anaerobic fermentation by Clostridium thermocellum 27405. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 72, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnusson, L.; Islam, R.; Cicek, N.; Sparling, R.; Levin, D.B. Direct hydrogen production from cellulosic waste materials with a single-step dark fermentation process. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 5398–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.L.; Rahman, A.; Rahim, R.A.; Aziz, S.A.; Shirai, Y.; Hassan, M.A. Optimization of biohydrogen production by Clostridium butyricum EB6 from palm oil mill effluent using response surface methodology. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2009, 34, 7475–7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wan, W. Optimization of fermentative hydrogen production process by response surface methodology. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 6976–6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.M.; Fan, Y.T.; Xing, Y.; Hou, H.W.; Zhang, M.L. Statistical optimization of process parameters on biohydrogen production from glucose by Clostridium. sp. Fanp2. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3146–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balusu, R.; Paduru, R.M.R.; Seenayya, G.; Reddy, G. Optimization of critical medium components using response surface methodology for ethanol production from cellulosic biomass by Clostridium thermocellum SS19. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 3025–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Oh, B.R.; Shin, H.J.; Eom, C.Y.; Kim, S.W. Statistical optimization of enzymatic saccharification and ethanol fermentation using food waste. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 1308–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.H.; Montgomery, D.C. Response Surface Methodology: Process and Product Optimization using Designed Experiments, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, R.; Özmihçi, S.; Cicek, N.; Sparling, R.; Levin, D.B. Enhanced cellulose fermentation and end-product synthesis by Clostridium thermocellum with varied nutrient compositions under carbon-excess conditions. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 48, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tutone, A.F.; Drummond, R.S.; Gardner, R.C.; Luan, S. A novel family of magnesium transport genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 2761–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dombek, K.M.; Ingram, L.O. Magnesium limitation and its role in apparent toxicity of ethanol during yeast fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1986, 52, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thanonkeo, P.; Laopaiboon, P.; Sootsuwan, K.; Yamada, M. Magnesium ions improve growth and ethanol production of Zymomonas mobilis under heat or ethanol stress. Biotechnology 2007, 6, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Goto, S.; Yonemura, K.; Sekine, E.; Okuma, T.; Takagi, K.; Hon-Nami, T.; Saiki, T. Effect of yeast extract and vitamin B12 on ethanol production from cellulose by Clostridium thermocellum I-1-B. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 734–736. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Geng, A.; He, Y.; Qian, C.; Yan, X.; Zhou, Z. Effect of key factors on hydrogen production from cellulose in a co-culture of Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium thermopalmarium. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 4029–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freier, D.; Mothershed, C.P.; Wiegel, J. Characterization of Clostridium thermocellum JW 20. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rydzak, T.; Levin, D.B.; Cicek, N.; Sparling, R. End-product induced metabolic shifts in Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 92, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, D.B.; Pitt, L.; Love, M. Biohydrogen production, prospects and limitations to practical application. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2004, 29, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamed, R.J.; Lobos, J.H.; Su, T.M. Effects of stirring and hydrogen on fermentation products of Clostridium thermocellum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 1216–1221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weimer, P.J.; Zeikus, J.G. Fermentation of cellulose and cellobiose by Clostridium thermocelurm in the presence and absence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977, 33, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grant, C.L.; Pramer, D. Minor element composition of yeast extract. J. Bacteriol. 1962, 84, 869–870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hafez, H.; Nakhla, G.; el Naggar, M.H.; Elbeshbishy, E.; Baghchehsaraee, B. Effect of organic loading on a novel hydrogen bioreactor. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ginkel, S.W.; Logan, B. Increased biological hydrogen production with reduced organic loading. Water Res. 2005, 39, 3819–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsharnouby, O.; Hafez, H.; Nakhla, G.; el Naggar, M.H. A critical literature review on biohydrogen production by pure cultures. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2013, 38, 4945–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.A.; Madia, A.; Demain, A.L. Chemically defined minimal medium for growth of the anaerobic cellulolytic thermophile Clostridium thermocellum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1981, 41, 1060–1062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.J.; Peterson, W.H.; Fred, E.B. Oxidation and reduction relations between substrate and products in the acetonebutyl alcohol fermentation. J. Biol. Chem. 1931, 91, 569–591. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Islam, R.; Sparling, R.; Cicek, N.; Levin, D.B. Optimization of Influential Nutrients during Direct Cellulose Fermentation into Hydrogen by Clostridium thermocellum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 3116-3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16023116

Islam R, Sparling R, Cicek N, Levin DB. Optimization of Influential Nutrients during Direct Cellulose Fermentation into Hydrogen by Clostridium thermocellum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015; 16(2):3116-3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16023116

Chicago/Turabian StyleIslam, Rumana, Richard Sparling, Nazim Cicek, and David B. Levin. 2015. "Optimization of Influential Nutrients during Direct Cellulose Fermentation into Hydrogen by Clostridium thermocellum" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16, no. 2: 3116-3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16023116

APA StyleIslam, R., Sparling, R., Cicek, N., & Levin, D. B. (2015). Optimization of Influential Nutrients during Direct Cellulose Fermentation into Hydrogen by Clostridium thermocellum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16(2), 3116-3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16023116