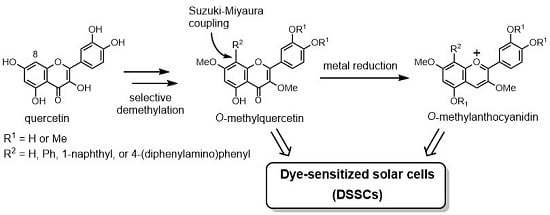

Synthesis of 8-Aryl-O-methylcyanidins and Their Usage for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Devices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of O-Methylquercetins

2.2. Synthesis of O-Methylanthocyanidins

2.3. Photovoltaic Property of DSSCs Using O-Methylquercetins

2.4. Photovoltaic Property of DSSCs Using O-Methylcyanidins

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

3.2. Synthesis of O-Methylquercetins

3.2.1. 3,7,3′,4′-tetra-O-Methyl-8-phenylquercetin (11)

3.2.2. 3,7,3′,4′-tetra-O-Methyl-8-(1-naphthyl)quercetin (12)

3.2.3. 3,7,3′,4′-tetra-O-Methyl-8-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl)quercetin (13)

3.2.4. 3,7-di-O-Methyl-8-phenylquercetin (14)

3.2.5. 3,7-di-O-Methyl-8-(1-naphthyl)quercetin (15)

3.2.6. 3,7-di-O-Methyl-8-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl)quercetin (16)

3.3. Synthesis of O-Methylanthocyanidins

3.3.1. 3,7,3′,4′-tetra-O-Methylcyanidin (18)

3.3.2. 3,7,4′-tri-O-Methylcyanidin (19)

3.3.3. 3,7-di-O-methylcyanidin (20).

3.3.4. 3,7-di-O-Methyl-8-phenylcyanidin (24)

3.4. Preparation of DSSCs

3.5. Measurement of the Cell Properties

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goto, T.; Kondo, T. Structure and molecular stacking of anthocyanins flower color variation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strack, D.; Wray, V. The anthocyanins. In The Flavonoids Advances in Research Science 1986; Harborne, J.B., Ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1994; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.A.; Grayer, R. Anthocyanins and other flavonoids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004, 21, 539–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, O.M.; Jordheim, M. The anthocyanins. In Flavonoids, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Applications; Andersen, O.M., Markham, K.R., Eds.; CPC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 471–551. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, K.; Mori, M.; Kondo, T. Blue flower color development by anthocyanins: From chemical structure to cell physiology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 884–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouillard, R.; Dangles, O. Flavonoids and flower colour. In The Flavonoids Advances in Research Science 1986; Harborne, J.B., Ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1994; pp. 569–586. [Google Scholar]

- Markakis, P. Anthocyanins as Food Colors; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, F.J.; Markakis, P.C. Food colorants: Anthocyanins. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1989, 28, 273–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuda, T. Regulation of adipocyte function by anthocyanins; possibility of preventing the metabolic syndrome. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins: Natural colorants with health-promoting properties. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norberto, S.; Silva, S.; Meireles, M.; Faria, A.; Pintado, M.; Calhau, C. Blueberry anthocyanins in health promotion: A metabolic overview. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1518–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagfeldt, A.; Boschloo, G.; Kloo, L.; Pettersson, H. Dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6595–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calogero, G.; Bartolotta, A.; Marco, G.D.; Carlo, A.D.; Bonaccorso, F. Vegetable-based dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3244–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everest, A.E. The production of anthocyanins and anthocyanidins. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1914, 87, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everest, A.E. The production of anthocyanins and anthocyanidins—Part II. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1914, 88, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, K.; Shibata, Y.; Kasiwagi, I. Study on anthocyanins; color variation in anthocyanins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1919, 41, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhabiri, M.; Figueiredo, P.; Fougerousse, A.; Brouillard, R. A convenient method for conversion of flavonols into anthocyanins. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 4611–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Kondo, T.; Oyama, K.-I. Process for the Preparation of Anthocyanidin Derivative. Japan Patent JP5382676, 8 January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oyama, K.-I.; Kawaguchi, S.; Yoshida, K.; Kondo, T. Synthesis of pelargonidin 3-O-6″-O-acetyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, an acylated anthocyanin, via the corresponding kaempferol glucoside. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 6005–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Kato, R.; Oyama, K.-I.; Kondo, T.; Yoshida, K. Efficient preparation of various O-methylquercetins by selective demethylation. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 957–961. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, Y.; Oyama, K.-I.; Kondo, T.; Yoshida, K. Synthesis of 8-aryl-3,5,7,3′,4′-penta-O-methylcyanidins from the corresponding quercetin derivatives by reduction with LiAlH4. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakone, K.; Kumara, G.R.R.A.; Kumarasighe, A.R.; Wijayantha, K.G.U.; Sirimanne, P.M. A dye-sensitized nano-porous solid-state photovoltaic cell. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 1995, 10, 1689–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepy, N.J.; Smestad, G.P.; Grätzel, M.; Zhang, J.Z. Ultrafast electron injection: Implications for a photoelectrochemical cell utilizing an anthocyanin dye-sensitized TiO2 nanocrystalline electrode. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 9342–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.H.; Su, Y.H.; Teoh, L.G.; Hon, M.H. Commercial and natural dyes as photosensitizers for a water-based dye-sensitized solar cell loaded with gold nanoparticles. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2008, 195, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, C.-Y.; Hsu, B.-D. Optimization of the dye-sensitized solar cell with anthocyanin as photosensitizer. Sol. Energy 2013, 98, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ku, S.-H.; Chen, S.-M.; Ali, M.A.; AlHemaid, F.A.M. Photoelectrochemistry for red cabbage extract as natural dye to develop a dye-sensitized solar cells. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Calogero, G.; Sinopoli, A.; Citro, I.; Marco, C.D.; Petrov, V.; Diniz, A.M.; Parola, A.J.; Pina, F. Synthetic analogues of anthocyanins as sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2013, 148, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, Y.; Maeda, T.; Iuchi, S.; Koga, N.; Murata, Y.; Wakamiya, A.; Yoshida, K. Characterization of dye-sensitized solar cells using five pure anthocyanidin 3-O-glucosides possessing different chromophores. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2017, 335, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Chu, J.; Wang, H.; Fu, X.; Quan, D.; Ding, H.; Yao, Q.; Yu, P. Regioserective iodination of flavonoids by N-iodosuccinimide under neutral conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 6345–6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaura, N.; Yanagi, T.; Suzuki, A. The palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of phenylboronic acid with haloarenes in the presence of bases. Synth. Commun. 1981, 11, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaura, N.; Suzuki, A. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organoboron compounds. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 2457–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callam, C.S.; Lowary, T.L. Suzuki cross-coupling reactions: Synthesis of unsymmetrical biaryls in the organic laboratory. J. Chem. Educ. 2001, 78, 947–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Rao, X.; Song, X.; Qiu, J.; Jin, Z. Palladium-catalyzed ligand-free and aqueous Suzuki reaction for the construction of (hetero)aryl-substituted triphenylamine derivatives. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurd, L. Quinone oxidation of flavenes and flavan-3,4-diols. Chem. Ind. 1966, 40, 1683–1684. [Google Scholar]

- Waiss, A.C., Jr.; Jurd, L. Synthesis of Flav-2-enes and Flav-3-enes. Chem. Ind. 1968, 23, 743–744. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.Y.; Schlichthörl, G.; Nozik, A.J.; Grätzel, M.; Frank, A.J. Charge recombination in dye-sensitized nanocrystalline TiO2 solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 2576–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.; Sodeyama, K.; Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Yanagida, M.; Tateyama, Y.; Han, L.A. A new factor affecting the performance of dye-sensitized solar cells in the presence of 4-tert-butylpyridine. Appl. Phys. Express 2012, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, H.; Tamaki, K.; Nakazaki, J.; Nishiyama, C.; Uchida, S.; Segawa, H.; Li, J. Kinetics versus energetics in dye-sensitized solar cells based on an ethynyl-linked porphyrin heterodimer. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 1426–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| penta-O-Methylquercetin | R | tetra-O-Methylquercetin | Yield (%) a |

| 8 | phenyl | 11 | 88 |

| 9 | 1-naphthyl | 12 | 78 |

| 10 | 4-(diphenylamino)phenyl | 13 | 87 |

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| tetra-O-Methylquercetin | R | di-O-Methylquercetin | Yield (%) a |

| 11 | phenyl | 14 | 85 |

| 12 | 1-naphthyl | 15 | 62 |

| 13 | 4-(diphenylamino)phenyl | 16 | 82 |

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-Methylquercetin | R | R1 | R2 | O-Methylanthocyanidin | Yield (%) a |

| 4 | H | Me | Me | 18 | 83 |

| 5 | H | H | Me | 19 | 75 |

| 6 | H | H | H | 20 | 71 |

| 14 | phenyl | H | H | 24 | 38 |

| Dye | Solvent | Jsc (mA/cm2) | Voc (mV) | FF | η (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| penta-OMeQ (2) | MeOH | 0.45 | 390 | 0.56 | 0.09 |

| tetra-OMeQ (4) | MeOH | 1.17 | 450 | 0.59 | 0.31 |

| tri-OMeQ (5) | MeOH | 2.04 | 439 | 0.60 | 0.54 |

| di-OMeQ (6) | MeOH | 4.65 | 445 | 0.40 | 0.82 |

| mono-OMeQ (7) | MeOH | 3.60 | 424 | 0.40 | 0.62 |

| quercetin (1) | MeOH | 3.09 | 459 | 0.43 | 0.60 |

| N719 | MeCN/tert-BuOH | 15.7 | 717 | 0.64 | 7.3 |

| Dye | Solvent | Jsc (mA/cm2) | Voc (mV) | FF | η (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-aryl-penta-OMeQ | |||||

| 8-phenyl (8) | MeOH | 0.21 | 257 | 0.59 | 0.03 |

| 8-naphthyl (9) | MeOH | 0.25 | 264 | 0.62 | 0.04 |

| 8-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl) (10) | MeOH | 0.28 | 350 | 0.59 | 0.06 |

| 8-aryl-tetra-OMeQ | |||||

| 8-phenyl (11) | CH2Cl2 | 2.15 | 486 | 0.63 | 0.66 |

| 8-naphthyl (12) | MeOH c | 2.35 | 663 | 0.70 | 1.04 |

| 8-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl) (13) | CH2Cl2 | 2.96 | 535 | 0.55 | 0.87 |

| 8-aryl-di-OMeQ | |||||

| 8-phenyl (14) | MeOH | 3.73 | 451 | 0.40 | 0.67 |

| 8-naphthyl (15) | MeOH | 4.55 | 436 | 0.44 | 0.88 |

| 8-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl) (16) | MeOH | 4.75 | 345 | 0.47 | 0.77 |

| Dye | Jsc (mA/cm2) | Voc (mV) | FF | η (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| penta-OMeCy (17) | 0.55 | 281 | 0.50 | 0.08 |

| tetra-OMeCy (18) | 0.71 | 284 | 0.63 | 0.13 |

| tri-OMeCy (19) | 0.51 | 266 | 0.63 | 0.08 |

| di-OMeCy (20) | 1.41 | 356 | 0.64 | 0.32 |

| 8-phenyl-penta-OMeCy (21) | 1.18 | 297 | 0.64 | 0.22 |

| 8-naphthyl-penta-OMeCy (22) | 0.58 | 346 | 0.60 | 0.12 |

| 8-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl)-penta-OMeCy (23) | 0.29 | 272 | 0.59 | 0.05 |

| 8-phenyl-di-OMeCy (24) | 2.43 | 328 | 0.65 | 0.52 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kimura, Y.; Oyama, K.-i.; Murata, Y.; Wakamiya, A.; Yoshida, K. Synthesis of 8-Aryl-O-methylcyanidins and Their Usage for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Devices. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020427

Kimura Y, Oyama K-i, Murata Y, Wakamiya A, Yoshida K. Synthesis of 8-Aryl-O-methylcyanidins and Their Usage for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Devices. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(2):427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020427

Chicago/Turabian StyleKimura, Yuki, Kin-ichi Oyama, Yasujiro Murata, Atsushi Wakamiya, and Kumi Yoshida. 2017. "Synthesis of 8-Aryl-O-methylcyanidins and Their Usage for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Devices" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 2: 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020427

APA StyleKimura, Y., Oyama, K. -i., Murata, Y., Wakamiya, A., & Yoshida, K. (2017). Synthesis of 8-Aryl-O-methylcyanidins and Their Usage for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Devices. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(2), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020427