An Operational Checklist of the Birds of Northwestern Italy (Piedmont and Aosta Valley)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Main Sources of Ornithological Information

2.3. Taxonomy

2.4. Coding System

- (a)

- Range Extension: This value is measured with reference to the UTM 10 × 10 km squares that comprise the regional area (n = 343). The number of squares occupied by each species was extracted from the Italian Atlas of Breeding Birds [36]. This criterion includes four classes ranging from the more (with 10% of occupied squares or less) to the less vulnerable conditions (with more than 60% of occupied squares).

- (b)

- Population Abundance: This value represents the number of pairs occurring in the PAV region. The figure was based on previous estimates [20] and includes updated data collected through the Italian Breeding Bird Monitoring Program (MITO2000) [47] and the Farmland Bird Index (FBI) project [48,49]. This criterion includes seven size classes ranging from the most vulnerable (no more than 1–9 breeding pairs) to the class with the lowest risk (hundreds of thousands of breeding pairs). An additional class “0” was reserved for species not confirmed to be breeding.

- (c)

- Population Trend: The results of the Farmland Bird Index (FBI) project were used to estimate the population trends of many species, especially Passeriformes [48,49]. When available, actual census data or specific estimates were used [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. Another source of information was the variation in the number of occupied squares between the Regional Atlas of Breeding Birds [25] and the Italian Atlas of Breeding Birds [36].

3. Results

3.1. General Results

3.1.1. Notes on Selected Taxa

- Alectoris rufa: Genetic evidence of hybridization between A. rufa and A. chukar was detected in Alessandria province in individuals introduced from captivity [69].

- Phasianus colchicus: Introduced pheasants came from different subspecies (e.g., P. c. colchicus, P. c. mongolicus) and their hybrids.

- Tetrao urogallus: Last documented presence in Ossola Valley, with two birds shot in 1957 after decades of absence [70].

- Oxyura leucocephala: Some recent observations of birds near a Wildfowl Center where a breeding program was established; most likely escaped individuals. A few individuals of Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis have also been reported.

- Cygnus cygnus: Most, if not all, of the observations recorded from 2000 onward are attributed to escaped birds.

- Mergus merganser: First breeding was recorded in 1998 on Lake Maggiore. Since then, the population has regularly increased in terms of both numbers (about 20 pairs in 2019) and locations ([77] and GPSO unpubl.).

- Tadorna tadorna: Confirmed breeding of 1–4 pairs (VC 2017–2022) [78].

- Tadorna ferruginea: The presence of truly wild birds was previously questioned by Boano [79]. The current records refer to escaped birds or individuals from European feral populations.

- Callonetta leucophrys: After some observations during the breeding period in 2019, wild breeding of an escaped pair has recently been recorded in 2020 in CN province (GPSO unpubl.).

- Netta rufina: First breeding was recorded in 2006 [81]. Breeding pairs increased from 2 to 7 (2019) in two sites along the rivers Tanaro and Po [61]. Like in other mainland sites in Italy, it is unknown whether the colonization was due to an extension of the natural range extension or was improved by the addition of escaped birds from Wildfowl Centers [73].

- Aythya nyroca: Known for breeding at the beginning of the twentieth century [83], and reconfirmed as such, with growing numbers in the past decade (GPSO unpubl.). It is unclear whether escaped birds contributed to this expansion.

- Anas crecca: No reliable breeding records in the last thirty years. Therefore, the few records reported by Mingozzi et al. [25] should be considered insufficiently documented.

- Podiceps grisegena: Courtship and nest construction were recorded at Lake Viverone in 2018 without any other signs of breeding [89].

- Caprimulgus europaeus: The Piedmont breeding population has been referred to as C. e. meridionalis due to its biometric measurements [90].

- Porzana porzana: A single breeding event observed in 1984 [25].

- Zapornia pusilla: Given the detection difficulty of migrant birds, it is not surprising that only one observation has been recorded in the past decade (VC 2018) [89], whereas observations of the similar-in-behavior Zapornia parva have greatly increased.

- Porphyrio porphyrio: The first observation of this species in the PAV region was documented in Vercelli province in 2020 [97].

- Porphyrio alleni: The first record of this species in the PAV region was documented in Turin province in 2021 [97].

- Otis tarda: The only record in this century (TO 2005) is likely to be related to the reintroduction project in Great Britain [42].

- Threskiornis aethiopicus: 572 breeding pairs in 2018 [58].

- Plegadis falcinellus: Two breeding pairs in 2018 [58].

- Nycticorax nycticorax: 2005 breeding pairs in 2018 [58].

- Ardeola ralloides: 32 breeding pairs in 2018 [58].

- Bubulcus ibis: 776 breeding pairs in 2018 [58].

- Ardea cinerea: 1691 breeding pairs in 2018 [58].

- Ardea purpurea: 42 breeding pairs in 2018 [58].

- Egretta garzetta: 1984 breeding pairs in 2018 [58].

- Egretta gularis: The subspecific attribution of the observed birds remains uncertain but what is certain is that E. g. gularis was reported in Lombardy along the Sesia River on the PVA border [42].

- Phalacrocorax carbo: Ph. carbo sinensis is common year-round, with the first breeding record in 1989 [105] and 716 breeding pairs in 2018 [58]. Observations of Cormorants with a “gular pouch angle” of about 50° which can be attributed to Ph. carbo carbo [106] were recently documented (GPSO, unpubl.); however, ring recoveries or genetic confirmations are lacking.

- Burhinus oedicnemus: About 50 pairs were recorded in PAV in 2014 [52].

- Limnodromus scolopaceus: New to the region (VC 2020) [112].

- Chlidonias leucopterus: From 10 to 18 breeding pairs in the rice fields of Vercelli province during 1993–1999, now reduced to 1–2 pairs in 2018–2019 [117].

- Sterna paradisea: The first record of this species in the PAV region was in Cuneo province in 2021 [97].

- Falco biarmicus: The occurrence of some escaped birds from falconry cannot be ruled out.

- Falco cherrug: The occurrence of some escaped birds from falconry cannot be ruled out.

- Lanius senator: Once an uncommon breeding species [25], it rapidly decreased after the last confirmed breeding in Alessandria province in 2005 [136]. Afterward, there were only sparse records of these birds during the breeding season, without any evidence of certain breeding. The certain breeding record reported by Lardelli et al. [36] was not supported by evidence. It would be useful to review the taxonomic attribution of the museum specimens of L. s. niloticus and L. s. badius given the results of Nasuelli et al. [137].

- Corvus monedula: The occurrence of the nominate subspecies was confirmed only by the winter recovery of a ringed bird in Austria [39], but is likely less rare, as winter migrants often associated with the migrant Corvus frugilegus should come from the C. m. monedula (or C. m. soemmerringii) range.

- Alauda arvensis: Taxonomic information on the breeding population is insufficient. We agree with Shirirai and Svensson [140] and consider that A. a. cantarella is included in A. a. arvensis.

- Acrocephalus schoenobaenus: The only certain breeding record of the species in PAV was found in 2009 in Vercelli province [91], without any further breeding evidence in the following years.

- Delichon urbicum: We agree with Shirirai and Svensson [140] and include D. u. meridionale in the nominate subspecies.

- Cecropis daurica: The breeding sites in Alessandria province have been deserted since 1984 [25] and thus the species was considered extinct as a breeder in PAV according to Pavia and Boano [21]. However, recently, 1–2 breeding pairs were observed between 2011 and 2015 in the Langhe area [72,86,87,88,95].

- Aegithalos caudatus: The taxonomic assessment of the PAV birds is complex. In fact, birds morphologically resembling the subspecies A. c. italiae are not uncommon during the breeding period, whereas birds with a clear A. c. europaeus morphology prevail in winter. Although individuals with all-white heads have been recorded, there are no certain records of A. c. caudatus.

- Sylvia nisoria: The former population in the Ossola Valley and surrounding areas (Lake Orta) declined from 10 pairs in the 1980s to 1 pair in 2007 [141], when the last breeding record in PAV was documented.

- Sylvia cantillans: This species shows a fairly widespread breeding population in the alpine xerothermic areas of the Susa Valley, with some other scattered pairs. It is referred to as the taxon S. c. iberiae based on its morphology and genetic evidence [145]. In addition, single pairs in the Aosta Valley [34] and, although less certain, the southern valley of Cuneo province [146], can be referred to as the nominate subspecies based on their calls and morphology.

- Ficedula parva: In addition to one historical record (1875), one more recent and reliable observation (2002), not yet accepted by Ornitho.it, has been reported for the Ossola Valley [147].

- Ficedula hypoleuca: First confirmed breeding for PAV (and Italy) in 2021: a pair nested in May-June in a nest box in the Ossola Valley; however, a storm, unfortunately, destroyed the nest and the nestlings inside [148].

- Anthus richardi: Seven records dated back to the 1800s but none of the five most recent observations (2007–2021) were documented with accompanying photos or sound recordings.

- Emberiza schoeniclus: Once a relatively common breeder in marsh areas [25], although the population decreased in the last three decades, it is still considered a regular breeder with the nominate subspecies [21]. After 2009, only singing males have been found in less than ten sites, without evidence of certain breeding. The certain breeding record reported by Lardelli et al. [36] was due to an erroneous record (GPSO unpubl.).

3.1.2. Comments on the GCL and OCL

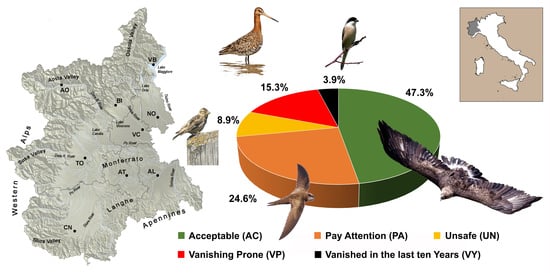

3.2. Red List of Breeding Birds 2010–2019

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- BiodiversityPhilippines. Available online: https://biodiversityphilippines.org/species-checklist-biodiversity-conservation/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Gaston, K.J. (Ed.) Biodiversity A Biology of Numbers and Differences; Blackwell Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Noss, R.E. Indicators for Monitoring Biodiversity: A Hierarchical Approach. Conserv. Biol. 1990, 4, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Stiller, J.; Deng, Y.; Armstrong, J.; Fang, Q.I.; Reeve, A.H.; Xie, D.; Chen, G.; Guo, C.; Faircloth, B.C.; et al. Dense sampling of bird diversity increases power of comparative genomics. Nature 2020, 587, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.H. Molecular biology as a tool for taxonomy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 20 (Suppl. S2), S117–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, D.M.; Moritz, C.; Mable, B.K. Molecular Systematics, 2nd ed.; Sinauer Associates Inc.: Sunderland, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Birds Are Very Useful Indicators for Other Kinds of Biodiversity. Available online: http://datazone.birdlife.org/sowb/casestudy/birds-are-very-useful-indicators-for-other-kinds-of-biodiversity#:~:text=Birds%20are%20very%20useful%20(although,comprehensively%20assessing%20biodiversity%20is%20enormous (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Corso, A.; Penna, V.; Gustin, M.; Maiorano, I.; Ferrandes, P. Annotated checklist of the birds from Pantelleria Island (Sicilian Channel, Italy): A summary of the most relevant data, with new species for the site and for Italy. Biodivers. J. 2012, 3, 407–428. [Google Scholar]

- McInerny, C.J.; Musgrove, A.J.; Gilroy, J.J.; Dudley, S.P.; The British Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee. The British List: A Checklist of Birds of Britain (10th edition). Ibis 2022, 164, 860–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, J.F.; Schulenberg, T.S.; Iliff, M.J.; Billerman, S.M.; Fredericks, T.A.; Gerbracht, J.A.; Lepage, D.; Sullivan, B.L.; Wood, C.L. The eBird/Clements Checklist of Birds of the World. Available online: https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Arrigoni degli Oddi, E. Elenco degli uccelli italiani per conoscere a prima vista lo stato esatto di ogni specie, riveduto al 31 dicembre 1912. Boll. Minist. Agric. Ind. E Commer. 1913, 12, 122. [Google Scholar]

- Moltoni, E. Elenco degli uccelli italiani con l’attuale nome scientifico e relativa pronuncia in riguardo all’accento. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1945, 15, 33–78. [Google Scholar]

- Moltoni, E.; Brichetti, P. Elenco degli Uccelli Italiani. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1978, 48, 65–142. [Google Scholar]

- Brichetti, P.; Massa, B. Check-list degli uccelli italiani. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1984, 54, 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brichetti, P.; Massa, B. Check-list degli uccelli italiani. Aggiornata a tutto il 1997. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1998, 68, 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. Check-list degli uccelli italiani aggiornata al 2014. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2015, 85, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccetti, N.; Fracasso, G.; COI, Commissione Ornitologica Italiana. CISO-COI Check-list of Italian birds-2020. Avocetta 2021, 45, 21–82. [Google Scholar]

- Checklist e Red List Nazionali. Available online: https://ciso-coi.it/coi/red-list-degli-uccelli-italiani/checklist-e-red-list-nazionali/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Boano, G.; Mingozzi, T. Analisi della situazione faunistica in Piemonte. Uccelli e Mammiferi. In Piemonte Ambiente-Fauna-Caccia; Regione Piemonte-EDA: Torino, Italy, 1981; pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Boano, G.; Pulcher, C. Check-list degli Uccelli di Piemonte e Val d’Aosta aggiornata al dicembre 2000. Boll. Mus. Reg. Sci. Nat. 2003, 20, 177–230. [Google Scholar]

- Pavia, M.; Boano, G. Check-list degli uccelli del Piemonte e della Valle d’Aosta aggiornata al dicembre 2008. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2009, 79, 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Morozzo, L.F. Déscription d’un Cygne sauvage pris en Piémont le 29 décembre 1788, suivie d’une notice de quelques autres oiseaux étrangers qui ont paru dans l’hiver de 1788-1789. Mem. R. Acad. Sci. Turin 1790, 9, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Girino, R.; Pozzi, D. Frassineto Po Dagli Albori Della Civiltà Umana Alle Soglie del Duemila; Marietti Ricerche: Casale Monferrato, Italy, 1989; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cervellini, M.; Zannini, P.; Di Musciano, M.; Fattorini, S.; Jiménez-Alfaro, B.; Rocchini, D.; Field, R.; Vetaas, O.R.; Severin, I.D.H.; Beierkuhnlein, C.; et al. A grid-based map for the Biogeographical Regions of Europe. Biodivers. Data J. 2020, 8, e53720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingozzi, T.; Boano, G.; Pulcher, C. Atlante degli Uccelli nidificanti in Piemonte e Val d’Aosta 1980–1984. In Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali; Monografie VIII: Torino, Italy, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mondino, G.P. Flora e vegetazione del Piemonte. In Regione Piemonte; L’Artistica Editrice: Torino, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli, F.A. Catalogue des Oiseaux du Piémont. Annales de l’Observatoire de L’Académie de Turin 1811, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Salvadori, T. Fauna d’Italia: Uccelli; Vallardi: Milano, Italy, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Bocca, M.; Maffei, G. Check-list degli uccelli della Valle d’Aosta. In Gli Uccelli Della Valle d’Aosta. Indagine Bibliografica e Dati Inediti; Ristampa con Aggiornamento al 1997; Bocca, M., Maffei, G., Eds.; Regione Autonoma Valle d’Aosta: Aosta, Italy, 1997; pp. 277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Assandri, G.; Ellena, I.; Marotto, P.; Soldato, G. Check-list degli Uccelli della Provincia di Torino aggiornata al dicembre 2006. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2008, 29, 323–354. [Google Scholar]

- Bionda, R.; Bordignon, L. Atlante degli uccelli nidificanti del Verbano Cusio Ossola. In Quaderni di Natura e Paesaggio del Verbano Cusio Ossola 6; Provincia VCO, Press Grafica: Gravellona Toce, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Casale, F.; Rigamonti, E.; Ricci, M.; Bergamaschi, L.; Cennamo, R.; Garanzini, A.; Mostini, L.; Re, A.; Toninelli, V.; Fasola, M. Gli uccelli della provincia di Novara (Piemonte, Italia): Distribuzione, abbondanza e stato di conservazione. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2017, 87, 3–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caula, B.; Beraudo, P.L. Ornitologia Cuneese; Primalpe: Cuneo, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maffei, G.; Baroni, D.; Bocca, M. Gli Uccelli Nidificanti in Valle d’Aosta; Testolin Editore: Sarre, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aimassi, G.; Reteuna, D. Uccelli nidificanti in Piemonte e Valle d’Aosta. Aggiornamento della distribuzione di 120 specie. Mem. Ass. Nat. Piem. 2007, 7, 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- Lardelli, R.; Bogliani, G.; Brichetti, P.; Caprio, E.; Celada, C.; Conca, G.; Fraticelli, F.; Gustin, M.; Janni, O.; Pedrini, P.; et al. Atlante Uccelli Nidificanti in Italia; Brambilla, M., Ed.; Edizioni Belvedere: Latina, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cucco, M.; Levi, L.; Maffei, G.; Pulcher, C. Atlante degli uccelli di Piemonte e Valle d’Aosta in inverno (1986-1992). In Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali; Monografie VIII: Torino, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano, S.G.; Tamietti, A.; Ferro, G.; Bandini, M.; Tibaldi, B. Gruppo Inanellatori Piemontesi e Valdostani. L’attività di inanellamento a scopo scientifico in Piemonte e Valle d’Aosta: Anni 1974–2016. Parte I. Generalità e non-Passeriformi. Tichodroma 2018, 8, 1–313. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano, S.G.; Tamietti, A.; Ferro, G.; Bandini, M.; Tibaldi, B.; Gruppo Inanellatori Piemontesi e Valdostani. L’attività di inanellamento a scopo scientifico in Piemonte e Valle d’Aosta: Anni 1974–2016. Parte II. Passeriformi e Ricatture. Tichodroma 2018, 9, 1–531. [Google Scholar]

- Spina, F.; Volponi, S. Atlante della migrazione degli uccelli in Italia. In Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare; I. non-Passeriformi.; I.S.P.R.A., Tipografia SCR: Roma, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spina, F.; Volponi, S. Atlante della migrazione degli uccelli in Italia. In Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare; II. Passeriformi.; I.S.P.R.A., Tipografia SCR: Roma, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boano, G. Gli uccelli accidentali in Piemonte e Valle d’Aosta. Aggiornamento 2005. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2007, 28, 305–366. [Google Scholar]

- Boano, G.; Mingozzi, T. Gli uccelli di comparsa accidentale nella regione piemontese. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 1985, 6, 3–67. [Google Scholar]

- Boano, G.; Mingozzi, T. Gli Uccelli di comparsa accidentale nella regione piemontese. Nota complementare. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 1986, 7, 217–218. [Google Scholar]

- Roan—Resoconto Ornitologico Annuale. Available online: https://www.gpso.it/news/roan/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Marotto, P. Re.P.Or.T. e Checklist. Available online: https://www.torinobirdwatching.net/re-p-or-t-e-checklist/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- MITO 2000. Monitoraggio Italiano Ornitologico. Available online: https://mito2000.it/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Toffoli, R. Programma di Sviluppo Rurale 2014–2020. In Monitoraggio Avifauna Nell’ambito del Calcolo del Farmland Bird Index e Woodland Bird Index; Unpublished 2020 Report; Istituto per le Piante da Legno e l’Ambiente: Piemonte, Italy, 2021; 61p. [Google Scholar]

- Toffoli, R. Monitoraggio dell’indicatore Trends of Index of Population of Farmland Birds (FBI), relativo agli Uccelli Nidificanti negli ambienti agricoli per l’anno 2021, previsto dal Programma di Sviluppo Rurale 2014–2000. Regione Autonoma Valle d’Aosta, Italy, 2021; 46p. Available online: https://www.regione.vda.it/allegato.aspx?pk=97065 (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Della Toffola, M.; Boano, G.; Assandri, G.; Caprio, E. Trent’anni di censimenti invernali degli uccelli acquatici in Piemonte e Valle d’Aosta (1979–2008). Tichodroma 2017, 3, 1–269. [Google Scholar]

- Infomigrans. Available online: http://www.parks.it/parco.alpi.marittime/gui_dettaglio.php?id_pubb=1093 (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Alessandria, G.; Bogliani, G.; Brambilla, M.; Gola, L.; Mantovani, S.; Marotto, P.; Vigo, E. L’occhione in Italia Nord-occidentale evoluzione storica e situazione attuale. In Occhione: Ricerca, Monitoraggio, Conservazione di Una Specie a Rischio; Biondi, M., Petrelli, L., Meschini, A., Eds.; Edizioni Belvedere: Latina, Italy, 2015; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bionda, R. Status of the population of Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos in the province of Verbano Cusio Ossola. Avocetta 2017, 41, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Caula, B.; Marotto, P. Il Gufo reale Bubo bubo in Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Analisi delle conoscenze attuali su status, distribuzione e biologia riproduttiva. Tichodroma 2021, 10, 1–126. [Google Scholar]

- Cucco, M.; Alessandria, G.; Bissacco, M.; Carpegna, F.; Fasola, M.; Gagliardi, A.; Gola, L.; Volponi, S.; Pellegrino, I. The spreading of the invasive sacred ibis in Italy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasce, P.; Fasce, L.; Bergese, F. Status of the Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos in the Western Alps. Avocetta 2017, 41, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fasola, M. (Ed.) Monitoraggio garzaie in Italia nord-occidentale 2018–47° anno. Rapporto 2018 del Gruppo Garzaie-Italia 2019. Available online: https://labzoo.unipv.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ReportGarzaieItalia2018.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Fasola, M.; Morganti, M. Breeding Populations of 12 Species of Colonial Waterbirds in Northwestern Italy, 1972–2018. LifeWatch ERIC. 2022. Available online: https://metadatacatalogue.lifewatch.eu/srv/eng/catalog.search#/metadata/bdc791a7-7678-44ad-a311-bd30c5086a06(accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Marotto, P.; Ruggieri, L.; Vaschetti, G. La Cicogna bianca (Ciconia ciconia) in Piemonte e in Provincia di Torino dal 1996 al 2014. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2017, 87, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingozzi, T.; Storino, P.; Venuto, G.; Venuto, G.; Alessandria, G.; Arcamone, E.; Urso, S.; Ruggieri, L.; Massetti, L.; Massolo, A. Autumn migration of Common Cranes Grus grus through the Italian Peninsula: New vs. historical flyways and their meteorological correlates. Acta Ornithol. 2013, 48, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebbia, C.; Alessandria, G. La popolazione di fistione turco Netta rufina nidificante in Piemonte (Italia nord-occidentale). Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2020, 90, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pavia, M.; Alessandria, G.; Della Toffola, M.; Pellegrino, I.; Tamietti, A.; Fasano, S.G. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2016–2022. Parte I: Progetti coordinati. Tichodroma, 2023; 12, in press. [Google Scholar]

- HBW and BirdLife Taxonomic Checklist v7. Available online: http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/taxonomy (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Guidelines for Rarities Committees. Available online: http://aerc.eu/guidelines.html (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Volet, B.; Schmid, H.; Winkler, R. Elenco degli uccelli della Svizzera. Ornithol. Beob. 2000, 97, 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Volet, B. Liste der Vogelarten der Schweiz. Ornithol. Beob. 2016, 113, 205–234. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, V.; Herrando, S.; Voříšek, P.; Franch, M.; Kipson, M.; Milanesi, P.; Martí, D.; Anton, M.; Klvaňová, A.; Kalyakin, M.V.; et al. European Breeding Bird Atlas 2: Distribution, Abundance and Change; European Bird Census Council & Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria, Version 3.1, Second Edition. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/10315 (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Silvano, F.; Meneguz, P.G.; Tizzani, P.; Pellegrino, I.; Negri, A.; Negri, E.; Boano, G. Biometric characterization of the Red-legged Partridges Alectoris rufa of northwestern Italy. Avocetta 2021, 45, 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Moltoni, E. La ricomparsa del Gallo cedrone—Tetrao urogallus—nell’Ossola (Alpi Lepontine). Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1958, 28, 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandria, G.; Della Toffola, M.; Fasano, S.G. (Eds.) Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2010. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2011, 32, 297–351. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandria, G.; Caprio, E.; Della Toffola, M.; Fasano, S.G.; Pavia, M. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2011. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2012, 33, 337–395. [Google Scholar]

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. The Birds of Italy; Anatidae-Alcidae; Edizioni Belvedere: Latina, Italy, 2018; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, I.; Cucco, M.; Follestad, A.; Boos, M. Lack of genetic structure in Greylag Goose (Anser anser) populations along the European Atlantic flyway. PeerJ 2015, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raspagni, D. Note sugli uccelli acquatici riscontrati sul Po di Valenza. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1963, 33, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nijman, V.; Aliabadian, M.; Roselaar, C.K. Wild hybrids of Lesser White-fronted Goose (Anser erythropus) × Greater White-fronted Goose (A. albifrons) (Aves: Anseriformes) from the European migratory flyway. Zool. Anz. A J. Comp. Zool. 2010, 248, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordignon, L.; Carabella, M.; Guenzani, W.; Guerrini, M.; Grattini, N.; Lardelli, R.; Piotti, G.; Pistono, C.; Saporetti, F.; Sighele, M.; et al. The Goosander Mergus merganser breeding population expansion and trend in North-western Italy. Avocetta 2018, 42, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Carpegna, F. (Gruppo Piemontese Studi Ornitologici, Carmagnola, Italy). Personal communication, 2022.

- Boano, G. La Casarca (Tadorna ferruginea) osservata anche in Piemonte. Gli Uccelli D’Italia 1981, 6, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pavia, M. Popolazione autosostentata di Anatra muta, Cairina moschata (Linnaeus 1758), in Piemonte. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2009, 69, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Caprio, E. Prima nidificazione di fistione turco, Netta rufina, in Piemonte. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2013, 82, 242–243. [Google Scholar]

- Marotto, P. Resoconto Provinciale Ornitologico Torinese (REPORT)—Anno XI. Available online: https://www.torinobirdwatching.net/dld/report/dld_server.php?file=2017_report (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Boano, G. Osservazioni sugli uccelli acquatici nella zona degli stagni di Ceresole d’Alba (CN) (anni 1970-1980) (Ordini: Podicipediformes, Ciconiformes, Anseriformes, Gruiformes, Charadriiformes). Alba Pompeia 1981, 2, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vaschetti, G. (Centro Cicogne Anatidi, Racconigi, Italy). Personal communication, 2022.

- Alessandria, G.; Della Toffola, M.; Fasano, S.G. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2007–2008. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2009, 30, 255–288. [Google Scholar]

- Assandri, G.; Bocca, M.; Caprio, E.; Fasano, S.G.; Pavia, M. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2013. Tichodroma 2016, 2, 1–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano, S.G.; Alessandria, G.; Assandri, G.; Caprio, E.; Pavia, M. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2014. Tichodroma 2017, 4, 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano, S.G.; Alessandria, G.; Assandri, G.; Caprio, E.; Pavia, M. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2015. Tichodroma 2017, 5, 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Marotto, P. Resoconto Provinciale Ornitologico Torinese (REPORT)—Anno XII. Available online: https://www.torinobirdwatching.net/dld/report/dld_server.php?file=2018_report (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Silvano, F.; Boano, G. Survival rates of adult European Nightjars Caprimulgus europaeus breeding in northwestern Italy. Ringing Migr. 2012, 27, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandria, G.; Della Toffola, M.; Fasano, S.G. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2009. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2010, 31, 279–329. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzetta, G. Osservazioni intorno agli Uccelli Ossolani. Ann. R. Acc. Agric. Torino 1893, 36, 127–172. [Google Scholar]

- Bordignon, L. Gli Uccelli del Biellese; Provincia di Biella, Eventi & Progetti Editore, Biella, Italy, 1998.

- Alba, R.; Assandri, G.; Boano, G.; Cravero, F.; Chamberlain, D. An assessment of the current and historical distribution of the Corncrake Crex crex in the Western Italian Alps. Avocetta 2021, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandria, G.; Caprio, E.; Della Toffola, M.; Fasano, S.G.; Pavia, M. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2012. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2013, 34, 307–367. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandria, G.; Carpegna, F. (Gruppo Piemontese Studi Ornitologici, Carmagnola, Italy). Personal communication, 2022.

- Marotto, P. Resoconto Provinciale Ornitologico Torinese (REPORT)—Anno XV. Available online: https://www.torinobirdwatching.net/2022/04/22/report-2021/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Aimassi, G.; Boano, G. Bonelli’s record of the demoiselle crane, Grus virgo from Piedmont, Italy. Arch. Nat. Hist. 2013, 40, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brichetti, P.; Truffi, G. Gli Uccelli di Comparsa Accidentale in Italia: Non-Passeriformes. In Manuale Pratico di Ornitologia; Brichetti, P., Gariboldi, A., Eds.; Edagricole: Bologna, Italy, 1999; pp. 122–167. [Google Scholar]

- Bordignon, L. Prima nidificazione di Cicogna nera. Ciconia nigra. Italia. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1995, 64, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fraissinet, M.; Bordignon, L.; Brunelli, M.; Caldarella, M.; Cripezzi, E.; Giustino, S.; Mallia, E.; Marrese, M.; Norante, N.; Urso, S.; et al. Breeding population of Black Stork, Ciconia nigra, in Italy between 1994 and 2016. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2018, 88, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boano, G. La Cicogna bianca in Piemonte. Presenza, nidificazione e problemi di conservazione (Aves, Ciconiidae). Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 1981, 2, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Della Toffola, M.; Alessandria, G.; Carpegna, F.; Re, A. Prima nidificazione in Piemonte di Spatola Platalea leucorodia. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1993, 63, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Maffei, G.; Della Toffola, M. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 1992. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 1993, 14, 259–279. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandria, G.; Carpegna, F.; Della Toffola, M. Il Cormorano Phalacrocorax carbo nella regione piemontese. Parte II. Distribuzione e biologia della popolazione nidificante (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae). Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2001, 22, 261–280. [Google Scholar]

- Bogliani, G. (Gruppo Piemontese Studi Ornitologici, Carmagnola, Italy). Personal communication, 2022.

- Sighele, M.; Corso, A. 2022 Considerazioni sulla presenza della Pavoncella armata Vanellus spinosus (Linaneus 1758) in Italia. Picus, 2022, in press.

- Zenattello, M.; Baccetti, N. Piano d’azione per il Chiurlottello (Numenius tenuirostris). In Quaderni Conservazione della Natura 7; Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica: Bologna, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bordigno, L.; Anselmetti, G. Prima nidificazione del Chiurlo maggiore, Numenius arquata, in Italia. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1999, 69, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, A.; Bordignon, L. L’Avifauna del S.I.C. “Baraggia di Candelo IT1130003”. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2014, 35, 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Marotto, P. Resoconto Provinciale Ornitologico Torinese (REPORT)—Anno XIV. Available online: http://www.torinobirdwatching.net/new/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/REPORT2020_definitivo.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Alessandria, G.; Della Toffola, M.; Fasano, S.G. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2006. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2008, 29, 355–398. [Google Scholar]

- Martorelli, G. Gli Uccelli d’Italia, 3rd ed.; Rizzoli: Milano, Italy, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Silvano, F. Nidificazione di Beccaccino, Gallinago gallinago, in Piemonte. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1986, 56, 267–268. [Google Scholar]

- Della Toffola, M.; Alessandria, G.; Carpegna, F. Nidificazione di Pettegola Tringa totanus in ambiente non alofilo in Italia. Avocetta 2003, 27, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Della Toffola, M. (Gruppo Piemontese Studi Ornitologici, Carmagnola, Italy). Personal communication, 2022.

- Alessandria, G.; Carpegna, F. Distribuzione, evoluzione e origine della popolazione nidificante di Larus michahellis in Piemonte. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2009, 78, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Marotto, P.; Soldato, G. L’avifauna della Riserva Naturale del Meisino e dell’Isolone Bertolla. Analisi ed esposizione dei dati raccolti tra il 1984 e il 2014. Tichodroma 2018, 7, 1–293. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandria, G.; Della Toffola, M.; Pulcher, C. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 1998. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2000, 21, 337–374. [Google Scholar]

- Bogliani, G.; Grattini, N. Le sterne nidificanti lungo il fiume Po: 40 anni dopo. Riassunti del XIX Convegno Italiano di Ornitologia. Tichodroma 2017, 6, 117–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, I.; Negri, A.; Cucco, M.; Mucci, N.; Pavia, M.; Salek, M.; Boano, G.; Randi, E. Phylogeography and Pleistocene refugia of the Little Owl Athene noctua inferred from mtDNA sequence data. Ibis 2014, 156, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, I.; Negri, A.; Boano, G.; Cucco, M.; Kristensen, T.; Pertoldi, C.; Randi, E.; Salek, M.; Mucci, N. Evidence for strong genetic structure in European populations of the little owl Athene noctua. J. Avian Biol. 2015, 46, 462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, I.; Cucco, M.; Calà, E.; Boano, G.; Pavia, M. Plumage coloration and morphometrics of the Little Owl Athene noctua in the Western Palearctic. J. Ornithol. 2020, 161, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasce, P.; Fasce, L. Prime nidificazioni con successo del Gipeto Gypaetus barbatus sulle Alpi occidentali italiane. Avocetta 2012, 33, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chiereghin, M.; Sartirana, F. Prima nidificazione con successo di Gipeto (Gypaetus barbatus) in Piemonte dall’inizio del progetto di reintroduzione della specie sulle Alpi. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2019, 89, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Toffoli, R. Distribuzione, successo riproduttivo e conservazione dell’Albanella minore (Circus pygargus) nella Pianura Padana occidentale (Aves, Accipitriformes). Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2000, 21, 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Marotto, P.; Bergamo, A. Accertata nidificazione di Nibbio reale (Milvus milvus) nella Pianura Padana occidentale. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2018, 88, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotto, P. (Gruppo Piemontese Studi Ornitologici, Carmagnola, Italy). Personal communication, 2022.

- Fasano, S.G.; Boano, G.; Ferro, G. 25 anni di inanellamento in Piemonte e Valle d’Aosta. Mem. Ass. Nat. Piem. 2005, 5, 1–224. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, J.M.; Olioso, G.; Cruaud, C.; Fuchs, J. Phylogeography of the Eurasian green woodpecker (Picus viridis). J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perktas, U.; Barrowclough, G.F.; Groth, J.G. Phylogeography and species limits in the green woodpecker complex (Aves: Picidae): Multiple Pleistocene refugia and range expansion across Europe and the Near East. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2011, 104, 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beraudo, P.L.; Bionda, R.; Boccardi, S.; Marotto, P.; Campora, M.; Gallo-Orsi, U.; Piana, M. Il Falco Pellegrino (Falco Peregrinus) in Piemonte. In Il Falco Pellegrino in Italia. Status, Biologia e Conservazione di una Specie di Successo; Brunelli, M., Gustin, M., Eds.; Edizioni Belvedere: Latina, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano, S.G. (Gruppo Piemontese Studi Ornitologici, Carmagnola, Italy). Personal communication, 2022.

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. The Birds of Italy; Pteroclidae-Locustellidae; Edizioni Belvedere: Latina, Italy, 2020; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandria, G.; Della Toffola, M.; Fasano, S.G. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2005. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2007, 28, 383–426. [Google Scholar]

- Nasuelli, M.; Ilahiane, L.; Boano, G.; Cucco, G.; Galimberti, A.; Pavia, M.; Pioltelli, E.; Shafaeipour, A.; Voelker, G.; Pellegrino, I. Phylogeography of Lanius senator in its breeding range: Conflicts between alpha taxonomy, subspecies distribution and genetics. Eur. Zool. J. 2022, 89, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keve, A. Studi sulle variazioni della Ghiandaia (Garrulus glandarius L.) d’Italia. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1966, 26, 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Shirihai, H.; Svensson, L. Handbook of Western Palearctic Birds; Volume II. Passerines: Flycatchers to Buntings; Helm: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shirihai, H.; Svensson, L. Handbook of Western Palearctic Birds; Volume I. Passerines: Larks to Warblers; Helm: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brichetti, P.; Fracasso, G. The Birds of Italy; Cisticolidae-Icteridae; Edizioni Belvedere: Latina, Italy, 2022; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Geroudet, P. La Fauvette orphée Sylvia hortensis dans la vallée d’Aoste. Nos Oiseaux 1967, 29, 163. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandria, G.; Fasano, S.G.; Della Toffola, M.; Boano, G.; Pulcher, C. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—d’Aosta. Anno 2003. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2005, 26, 321–360. [Google Scholar]

- Marotto, P. Resoconto Provinciale Ornitologico Torinese (REPORT)—Anno XIII. Available online: https://www.torinobirdwatching.net/dld/report/dld_server.php?file=2019_report (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Zuccon, D.; Pons, J.; Boano, G.; Chiozzi, G.; Gamauf, A.; Mengoni, C.; Nespoli, D.; Olioso, G.; Pavia, M.; Pellegrino, I.; et al. Type specimens matter: New insights on the systematics, taxonomy and nomenclature of the subalpine warbler (Sylvia cantillans) complex. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 190, 314–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, N.; Caula, B. (Cuneobirding, Cuneo, Italy). Personal communication, 2022.

- Giussani, L. Ficedula parva. Available online: https://www.ornitho.it/index.php?m_id=54&id=7990859(accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Bionda, R. Nidificazione di Balia nera (Ficedula hypoleuca) in Val d’Ossola (Verbano-Cusio-Ossola, Piemonte). Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2023, in press.

- Tiso, E.; Quaglini, V. Nidificazione della Balia dal collare, Ficedula albicollis, in provincial di Alessandria nel 1984. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 1985, 55, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Drovetski, S.V.; Fadeev, I.V.; Raković, M.; Lopes, R.J.; Boano, G.; Pavia, M.; Koblik, E.A.; Lohman, Y.V.; Red’kin, Y.A.; Aghayan, S.A.; et al. A test of the European Pleistocene refugial paradigm, using a Western Palaearctic endemic bird species. Proc. R. Soc. B 2018, 285, 20181606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pavia, M.; Drovetski, S.V.; Boano, G.; Conway, K.W.; Pellegrino, I.; Voelker, G. Elevation of two subspecies of Dunnock Prunella modularis to species rank. Bull. BOC 2021, 141, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bionda, R. Motacilla alba Yarrelli. Available online: https://www.ornitho.it/index.php?m_id=54&id=13235606(accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Siddi, L. Motacilla alba Yarrelli. Available online: https://www.ornitho.it/index.php?m_id=54&mid=421383(accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Camusso, N. Gli uccelli del basso Piemonte; Fratelli Dumolard: Milano, Italy, 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandria, G.; Boano, G.; Della Toffola, M.; Fasano, S.G.; Pulcher, C.; Toffoli, R. Resoconto Ornitologico per la Regione Piemonte—Valle d’Aosta. Anno 2002. Riv. Piem. St. Nat. 2004, 25, 391–430. [Google Scholar]

- Lietti, A. (Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, Lentate sul Seveso, Italy). Personal communication, 2022.

- LIFE Northern Bald Ibis. Available online: https://www.waldrapp.eu/en/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Massa, B.; Ientile, R.; Aradis, A.; Surdo, S. One hundred and fifty years of ornithology in Sicily One hundred and fifty years of ornithology in Sicily, with an unknown manuscript by Joseph Whitaker. Biodivers. J. 2021, 12, 27–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grussu, M. New checklist of the birds of Sardinia (Italy). Edition 2022. Aves Ichnusae 2022, 12, 3–62. [Google Scholar]

- La Gioia, G.; Liuzzi, C.; Albanese, G.; Nuovo, G. Check-list degli Uccelli della Puglia, aggiornata al 2009. Riv. Ital. Ornit. 2010, 79, 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fracasso, G.; Mezzavilla, F.; Scarton, F. Check-List degli Uccelli del Veneto (Maggio 2010). In Atti 6° Convegno Faunisti Veneti; Bon, M., Mezzavilla, F., Scarton, F. Eds. Boll. Mus. Civ. St. Nat. Venezia 2011, 61, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli, M.; Fraticelli, F.; Molajoli, R. Check-list degli uccelli del Lazio aggiornata al 2019. Alula 2019, 26, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur, R.H.; Wilson, E.O. The Theory of Island Biogeography; Princeton University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, F.W. The canonical distribution of commonness and rarity: Part, I. Ecology 1962, 43, 185–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, I. The Migration Ecology of Birds; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gustin, M.; Nardelli, R.; Brichetti, P.; Battistoni, A.; Rondinini, C.; Teofili, C. Lista Rossa IUCN Degli Uccelli Nidificanti in Italia 2021. Comitato Italiano IUCN e Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare, Roma. Available online: http://www.iucn.it/pdf/Lista-Rossa-Uccelli-Nidificanti-2021.pdf(accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Robinson, W.D.; Hallman, T.A.; Curtis, J.R. Benchmarking the avian diversity of Oregon in an era of rapid change. Northwest Nat. 2020, 101, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani, L.; Massimino, D.; Orioli, V.; Bottoni, L.; Massa, R. Assessment of population trends of common breeding birds in Lombardy, Northern Italy, 1992–2007. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2009, 21, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Class | Code |

|---|---|---|

| AERC Categories | A | Taxon that has been recorded in a wild state at least once since 1 January 1950. |

| B | Taxon that has been recorded in a wild state between 1800 and 1949. | |

| C | Taxon that has been released or escaped; species that have established self-supporting breeding populations in their own countries; birds coming from a category C population in another country (with the species not breeding in their own country). | |

| D | Every taxon, unless it is almost certainly a genuine vagrant (in which case it enters cat. A) or an escape from captivity (cat. E). | |

| E | Taxon recorded as introductions, human-assisted transportees, or escapees from captivity whose breeding populations (if any) are thought not to be self-sustaining. | |

| General status | 1 | Regular: taxon recorded in at least 9 out of the last 10 years. |

| 2 | Irregular: taxon recorded more than 10 times and in more than 5 years since 1950 but in fewer than 9 out of the last 10 years. | |

| 3 | Vagrant: taxon recorded 1–10 times or in 1–5 years since 1950. | |

| 4 | Taxon recorded at least once but not since 1950. | |

| Breeding status | 1 | Regular breeder: recorded breeding in at least 9 out of the last 10 years. |

| 2 | Irregular breeder: recorded breeding more than 3 times overall but in less than 9 out of the last 10 years. | |

| 3 | Occasional breeder: recorded breeding 1–3 times. | |

| 4 | Former breeder: taxa that regularly bred during an earlier period but have not been recorded breeding in the last 10 years. | |

| 0 | Taxon never recorded breeding. |

| Category | Class | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Occurrence | YR | Year-round/Resident: taxon present in all months of the year. |

| YM | Year-round/Migrant/: migratory taxon, present in the region with a population partially resident. | |

| MS | Migrant/Summer: taxon present mainly from March/April to September/October. | |

| MW | Migrant/Winter: taxon present mainly from September/October to March/April. | |

| MT | Migrant/Strictly Transient: migratory taxon present in pre- and/or post-nuptial periods. | |

| VA | Vagrant: taxon recorded in total 1–10 times or in 1–5 years from 1950 and recorded almost once in the decade. | |

| VE | Former Vagrant, now Escaped: taxon recorded 1–10 times or in 1–5 years from 1950 but recorded only as escaped in the last decade. | |

| Breeding Status | BC | Breeder/Confirmed |

| BN | Breeder/New: not nesting in the previous decade, whether regular or irregular. | |

| BP | Breeder/Past: breeding in the previous but not in the present decade. |

| Category | Class | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Range Extension | 1 | <10% of occupied UTM 10 × 10 km squares |

| 2 | >10–<40% of occupied UTM 10 × 10 km squares | |

| 3 | >40–<60% of occupied UTM 10 × 10 km squares | |

| 4 | >60% of occupied UTM 10 × 10 km squares | |

| Population abundance | 0 | Breeding not ascertained: only one or a few singing or territorial males. |

| 1 | unit (1–9 pairs) | |

| 2 | tens (10–99 pairs) | |

| 3 | hundreds (100–999 pairs) | |

| 4 | thousands (1000–9999 pairs) | |

| 5 | tens of thousands (pairs) | |

| 6 | hundreds of thousands (pairs) | |

| Population Trend | + | Increasing |

| − | Decreasing | |

| = | Stable | |

| Unknown/Insufficiently known |

| Risk Level | Code |

|---|---|

| AC | Acceptable: taxon with range extension ≥ 2, abundance ≥ 3, and no clear sign of decreasing population trend in the last 10 years. |

| PA | Pay Attention: taxon with range extension ≤ 3 and population abundance > 2; taxon with range extension > 1 is included here if its population trend is decreasing. |

| UN | Unsafe: taxon with range extension = 1 and population abundance = 2, but no clear sign of decreasing population trend in the decade 2010–2019; taxon with range extension = 2 is included here if its population trend is decreasing. |

| VP | Vanishing Prone: taxon with range extension = 1 and population abundance = 1; taxon with population trend = 2 is included here if its population trend is decreasing. We also include here taxa that are almost extinct as breeders but with probable breeding records in the current decade. |

| VY | Vanished in the last ten years: taxon ascertained as breeding in the previous decade (2000–2009) but no longer reported as certain or probable breeders [67] in the following decade (2010–2019). |

| GCL Updated to December 2022 | OCL 2010–2019 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species Subspecies | English Name | AERC | OC | BR | POP | RL | Note |

| Galliformes Odontophoridae | |||||||

| Colinus virginianus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Northern Bobwhite | C11 | YR | BCr | 3− | AC | |

| C. v. virginianus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Phasianidae | |||||||

| Coturnix coturnix (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Quail | A11 | MSr | BCr | 4 | PA | |

| C. c. coturnix (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Coturnix japonica Temminck and Schlegel, 1848 | Japanese Quail | E10 | YR | 1 | |||

| Alectoris graeca (Meisner, 1804) | Rock Partridge | A11 | YR | BCr | 4− | PA | |

| A. g. saxatilis (Bechstein, 1805) | |||||||

| Alectoris rufa (Linnaeus, 1758) | Red-legged Partridge | AC11 | YR | BCr | 3− | PA | 2 |

| A. r. rufa (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Phasianus colchicus Linnaeus, 1758 | Common Pheasant | C11 | YR | BCr | 4− | AC | 3 |

| Perdix perdix (Linnaeus, 1758) | Gray Partridge | AC11 | YR | BCr | 2− | VP | |

| P. p. perdix (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Bonasa bonasia (Linnaeus, 1758) | Hazel Grouse | A11 | YR | BCr | 2+ | UN | 4 |

| B. b. styriaca (von Jordans and Schiebel, 1944) | |||||||

| Lagopus muta (Montin, 1781) | Rock Ptarmigan | A11 | YR | BCr | 4− | PA | |

| L. m. helvetica (Thienemann, 1829) | |||||||

| Tetrao urogallus Linnaeus, 1758 | Western Capercaillie | A34 | 5 | ||||

| T. u. crassirostris C. L. Brehm, 1831 | |||||||

| Lyrurus tetrix (Linnaeus, 1758) | Black Grouse | A11 | YR | BCr | 4− | PA | |

| L. t. tetrix (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Anseriformes Anatidae | |||||||

| Oxyura leucocephala (Scopoli, 1769) | White-headed Duck | B40 | 6 | ||||

| Cygnus olor (J. F. Gmelin, 1789) | Mute Swan | AC11 | YR | BCr | 2+ | AC | |

| Cygnus cygnus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Whooper Swan | AE30 | VE | 7 | |||

| Cygnus columbianus (Ord, 1815) | Tundra Swan | A30 | VA | ||||

| C. c. bewickii Yarrell, 1830 | |||||||

| Branta bernicla (Linnaeus, 1758) | Brent Goose | AE30 | |||||

| B. b. bernicla (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Branta leucopsis (Bechstein, 1803) | Barnacle Goose | DE10 | YR | 8 | |||

| Branta ruficollis (Pallas, 1769) | Red-breasted Goose | A30 | VA | ||||

| Branta canadensis (Linnaeus, 1758) | Canada Goose | DE10 | YR | ||||

| Anser anser (Linnaeus, 1758) | Greylag Goose | AE12 | YR | BN | 1 | AC | 9 |

| A. a. anser (Linnaeus, 1758) | AE12 | YR | BN | 1 | AC | ||

| A. a. rubrirostris Swinhoe, 1871 | A10 | MWr | |||||

| Anser fabalis (Latham, 1787) | Bean Goose | A20 | MWi | ||||

| A. a. rossicus Buturlin, 1933 | |||||||

| Anser albifrons (Scopoli, 1769) | Great White-fronted Goose | A20 | MWi | ||||

| A. a. albifrons (Scopoli, 1769) | |||||||

| Anser erythropus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Lesser White-fronted Goose | A30 | 10 | ||||

| Clangula hyemalis (Linnaeus, 1758) | Long-tailed Duck | A20 | MTi | ||||

| Somateria mollissima (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Eider | A20 | MWi | ||||

| S. m. mollissima (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Melanitta fusca (Linnaeus, 1758) | Velvet Scoter | A10 | MWr | ||||

| Melanitta nigra (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Scoter | A20 | MWi | ||||

| Bucephala clangula (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Goldeneye | A10 | MWr | ||||

| B. c. clangula (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Mergellus albellus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Smew | A20 | MWi | ||||

| Mergus merganser Linnaeus, 1758 | Goosander | A11 | YMr | BCr | 2+ | UN | 11 |

| M. m. merganser Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Mergus serrator Linnaeus, 1758 | Red-breasted Merganser | A10 | MWr | ||||

| Alopochen aegyptiaca (Linnaeus, 1766) | Egyptian Goose | E12 | YR | BN | 1 | ||

| Tadorna tadorna (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Shelduck | AD12 | YMr | BN | 1 | VP | 12 |

| Tadorna ferruginea (Pallas, 1764) | Ruddy Shelduck | DE10 | YMi | 13 | |||

| Cairina moschata (Linnaeus, 1758) | Muscovy Duck | E13 | YR | BP | 14 | ||

| Callonetta leucophrys (Vieillot, 1816) | Ringed Teal | E23 | YR | 15 | |||

| Aix galericulata (Linnaeus, 1758) | Mandarin Duck | CE11 | YMr | BCr | 2+ | AC | |

| Netta rufina (Pallas, 1773) | Red-crested Pochard | AD11 | YMr | BCr | 1 | VP | 16 |

| Aythya ferina (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Pochard | A12 | YMr | BCi | 1 | VP | 17 |

| Aythya nyroca (Güldenstädt, 1770) | Ferruginous Duck | AD12 | YMr | BN | 1 | VP | 18 |

| Aythya collaris (Donovan, 1809) | Ring-necked Duck | A30 | VA | ||||

| Aythya fuligula (Linnaeus, 1758) | Tufted Duck | A11 | YMr | BCr | 2+ | UN | |

| Aythya marila (Linnaeus, 1761) | Greater Scaup | A20 | MWi | ||||

| A. m. marila (Linnaeus, 1761) | |||||||

| Spatula querquedula (Linnaeus, 1758) | Garganey | A11 | MSr | BCr | 1 | VP | |

| Spatula clypeata (Linnaeus, 1758) | Northern Shoveler | A13 | YMr | 19 | |||

| Sibirionetta formosa (Georgi, 1775) | Baikal Teal | D30 | |||||

| Mareca strepera (Linnaeus, 1758) | Gadwall | A12 | YMr | BCi | 1 | VP | 20 |

| M. s. strepera (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Mareca penelope (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Wigeon | A10 | MWr | ||||

| Anas platyrhynchos Linnaeus, 1758 | Mallard | AC11 | YMr | BCr | 4= | AC | |

| A. p. platyrhynchos Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Anas acuta Linnaeus, 1758 | Northern Pintail | A10 | MWr | ||||

| Anas crecca Linnaeus, 1758 | Common Teal | A10 | YMr | 21 | |||

| A. c. crecca Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Podicipediformes Podicipedidae | |||||||

| Tachybaptus ruficollis (Pallas, 1764) | Little Grebe | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3+ | AC | |

| T. r. ruficollis (Pallas, 1764) | |||||||

| Podiceps grisegena (Boddaert, 1783) | Red-necked Grebe | A10 | MWr | 22 | |||

| P. g. grisegena (Boddaert, 1783) | |||||||

| Podiceps cristatus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Great Crested Grebe | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3+ | AC | |

| P. c. cristatus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Podiceps auritus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Horned Grebe | A10 | MWr | ||||

| P. a. auritus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Podiceps nigricollis C. L. Brehm, 1831 | Black-necked Grebe | A12 | YMr | BN | 1 | VP | 23 |

| P. n. nigricollis C. L. Brehm, 1831 | |||||||

| Phoenicopteriformes Phoenicopteridae | |||||||

| Phoenicopterus roseus Pallas, 1811 | Greater Flamingo | A20 | MTi | ||||

| Columbiformes Columbidae | |||||||

| Columba livia J. F. Gmelin, 1789 | Rock Dove | C11 | YR | BCr | 6+ | AC | |

| C. l. var. domestica | Feral Pigeon | ||||||

| Columba oenas Linnaeus, 1758 | Stock Dove | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3+ | AC | |

| C. o. oenas Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Columba palumbus Linnaeus, 1758 | Common Woodpigeon | A11 | YMr | BCr | 6+ | AC | |

| C. p. palumbus Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Streptopelia turtur (Linnaeus, 1758) | European Turtle Dove | A11 | MSr | BCr | 5− | PA | |

| S. t. turtur (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Streptopelia decaocto (Frivaldszky, 1838) | Eurasian Collared Dove | A11 | YR | BCr | 6+ | AC | |

| Pterocliformes Pteroclidae | |||||||

| Syrrhaptes paradoxus (Pallas, 1773) | Pallas’s Sandgrouse | B40 | |||||

| Pterocles alchata (Linnaeus, 1766) | Pin-tailed Sandgrouse | B40 | |||||

| P. a. caudacutus (S. G. Gmelin, 1774) | |||||||

| Caprimulgiformes Caprimulgidae | |||||||

| Caprimulgus europaeus Linnaeus, 1758 | European Nightjar | A11 | MSr | BCr | 3= | AC | 24 |

| C. e. europaeus Linnaeus, 1758 | A10 | MTr | |||||

| C. e. meridionalis E. J. O. Hartert, 1896 | A11 | MSr | BCr | 3= | AC | ||

| Apodidae | |||||||

| Tachymarptis melba (Linnaeus, 1758) | Alpine Swift | A11 | MSr | BCr | 4+ | AC | |

| T. m. melba (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Apus pallidus (Shelley, 1870) | Pallid Swift | A11 | MSr | BCr | 4= | PA | |

| A. p. brehmorum E. J. O. Hartert, 1901 | |||||||

| Apus apus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Swift | A11 | MSr | BCr | 5 | AC | |

| A. a. apus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Cuculiformes Cuculidae | |||||||

| Clamator glandarius (Linnaeus, 1758) | Great Spotted Cuckoo | A20 | MTi | 25 | |||

| Coccyzus americanus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Yellow-billed Cuckoo | B40 | |||||

| Cuculus canorus Linnaeus, 1758 | Common Cuckoo | A11 | MSr | BCr | 4 | AC | |

| C. c. canorus Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Gruiformes Rallidae | |||||||

| Rallus aquaticus Linnaeus, 1758 | Western Water Rail | A11 | YMr | BCr | 2 | UN | |

| R. a. aquaticus Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Crex crex (Linnaeus, 1758) | Corncrake | A14 | MSr | 26 | |||

| Porzana porzana (Linnaeus, 1766) | Spotted Crake | A13 | MTr | 27 | |||

| Zapornia parva (Scopoli, 1769) | Little Crake | A12 | MSr | BN | 1 | VP | 28 |

| Zapornia pusilla (Pallas, 1776) | Baillon’s Crake | A20 | MTi | 29 | |||

| Z. p. intermedia (Hermann, 1804) | |||||||

| Porphyrio porphyrio (Linnaeus, 1758) | Purple Swamphen | A30 | 30 | ||||

| P. p. porphyrio (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Porphyrio alleni T. R. H. Thomson, 1842 | Allen’s Gallinule | A30 | 31 | ||||

| Gallinula chloropus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Gallinule | A11 | YMr | BCr | 4− | PA | |

| G. c. chloropus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Fulica atra Linnaeus, 1758 | Common Coot | A11 | YMr | BCr | 4+ | AC | |

| F. a. atra Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Gruidae | |||||||

| Anthropoides virgo (Linnaeus, 1758) | Demoiselle Crane | B40 | 32 | ||||

| Grus grus Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Crane | A10 | MWr | ||||

| G. g. grus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Otidiformes Otididae | |||||||

| Tetrax tetrax (Linnaeus, 1758) | Little Bustard | A30 | VA | ||||

| Otis tarda Linnaeus, 1758 | Great Bustard | BD30 | 33 | ||||

| O. t. tarda Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Gaviiformes Gaviidae | |||||||

| Gavia stellata (Pontoppidan, 1763) | Red-throated Loon | A10 | MWr | ||||

| Gavia arctica (Linnaeus, 1758) | Arctic Loon | A10 | MWr | ||||

| G. a. arctica (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Gavia immer (Brünnich, 1764) | Common Loon | A30 | VA | ||||

| Procellariiformes Procellariidae | |||||||

| Fulmarus glacialis (Linnaeus, 1761) | Northern Fulmar | A30 | |||||

| F. g. auduboni Bonaparte, 1857 | |||||||

| Calonectris diomedea (Scopoli, 1769) | Scopoli’s Shearwater | B40 | |||||

| Puffinus lherminieri Lesson, 1839 | Audubon’s Shearwater | B40 | |||||

| P. l. baroli (Bonaparte, 1857) | |||||||

| Ciconiiformes Ciconiidae | |||||||

| Ciconia nigra (Linnaeus, 1758) | Black Stork | A11 | YMr | BCr | 1 | VP | 34 |

| Ciconia ciconia (Linnaeus, 1758) | White Stork | AC11 | YMr | BCr | 2+ | PA | 35 |

| C. c. ciconia (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Pelecaniformes Threskiornithidae | |||||||

| Platalea leucorodia Linnaeus, 1758 | Eurasian Spoonbill | A12 | YMr | BP | VY | 36 | |

| P. l. leucorodia Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Threskiornis aethiopicus (Latham, 1790) | African Sacred Ibis | C11 | YR | BCr | 3+ | AC | 37 |

| Geronticus eremita Linnaeus, 1758 | Northern Bald Ibis | E20 | YMi | ||||

| Plegadis falcinellus (Linnaeus, 1766) | Glossy Ibis | A12 | YMr | BCi | 1 | VP | 38 |

| Ardeidae | |||||||

| Botaurus stellaris (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Bittern | A11 | YMr | BCr | 2+ | UN | |

| B. s. stellaris (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Ixobrychus minutus (Linnaeus, 1766) | Common Little Bittern | A11 | MSr | BCr | 2− | UN | |

| I. m. minutus (Linnaeus, 1766) | |||||||

| Ixobrychus eurhythmus (Swinhoe, 1873) | Schrenck’s Bittern | B40 | |||||

| Nycticorax nycticorax (Linnaeus, 1758) | Black-crowned Night Heron | A11 | MSr | BCr | 4− | PA | 39 |

| N. n. nycticorax (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Ardeola ralloides (Scopoli, 1769) | Squacco Heron | A11 | MSr | BCr | 2= | UN | 40 |

| A. r. ralloides (Scopoli, 1769) | |||||||

| Bubulcus ibis (Linnaeus, 1758) | Cattle Egret | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3+ | PA | 41 |

| B. i. ibis (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Ardea cinerea Linnaeus, 1758 | Grey Heron | A11 | YMr | BCr | 4− | PA | 42 |

| A. c. cinerea Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Ardea purpurea Linnaeus, 1766 | Purple Heron | A11 | MSr | BCr | 2= | UN | 43 |

| A. p. purpurea Linnaeus, 1766 | |||||||

| Ardea alba Linnaeus, 1758 | Great White Egret | A12 | YMr | BN | 1 | VP | 44 |

| A. a. alba Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Egretta garzetta (Linnaeus, 1766) | Little Egret | A11 | YMr | BCr | 4− | PA | 45 |

| E. g. garzetta (Linnaeus, 1766) | |||||||

| Egretta gularis (Bosc, 1792) | Western Reef Egret | D30 | VE | 46 | |||

| Pelecanidae | |||||||

| Pelecanus onocrotalus Linnaeus, 1758 | Great White Pelican | BD30 | VE | 47 | |||

| Suliformes Sulidae | |||||||

| Morus bassanus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Northern Gannet | A30 | |||||

| Phalacrocoracidae | |||||||

| Microcarbo pygmaeus (Pallas, 1773) | Pygmy Cormorant | A10 | YMr | ||||

| Phalacrocorax carbo (Linnaeus, 1758) | Great Cormorant | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3+ | AC | 48 |

| P. c. carbo (Linnaeus, 1758) | A30 | VA | |||||

| P. c. sinensis (Staunton, 1796) | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3+ | AC | ||

| Charadriiformes Burhinidae | |||||||

| Burhinus oedicnemus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Thick-knee | A11 | MSr | BCr | 2+ | UN | 49 |

| B. o. oedicnemus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Haematopodidae | |||||||

| Haematopus ostralegus Linnaeus, 1758 | Eurasian Oystercatcher | A20 | MTi | ||||

| H. o. ostralegus Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Recurvirostridae | |||||||

| Recurvirostra avosetta Linnaeus, 1758 | Pied Avocet | A20 | MTi | ||||

| Himantopus himantopus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Black-winged Stilt | A11 | MSr | BCr | 3− | PA | |

| H. h. himantopus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Charadriidae | |||||||

| Pluvialis squatarola (Linnaeus, 1758) | Grey Plover | A10 | MTr | ||||

| P. s. squatarola (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Pluvialis apricaria (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Golden Plover | A10 | MWr | ||||

| P. a. apricaria (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Eudromias morinellus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Dotterel | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Charadrius hiaticula Linnaeus, 1758 | Common Ringed | A10 | MSr | ||||

| C. h. hiaticula Linnaeus, 1758 | Plover | ||||||

| Charadrius dubius Scopoli, 1786 | Little Ringed Plover | A11 | MSr | BCr | 2− | UN | |

| C. d. curonicus J. F. Gmelin, 1789 | |||||||

| Charadrius alexandrinus Linnaeus, 1758 | Kentish Plover | A23 | MTi | 50 | |||

| C. a. alexandrinus Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Vanellus vanellus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Northern Lapwing | A11 | YMr | BCr | 4= | AC | |

| Vanellus spinosus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Spur-winged Lapwing | D30 | 51 | ||||

| Vanellus gregarius (Pallas, 1771) | Sociable Lapwing | A30 | VA | ||||

| Scolopacidae | |||||||

| Numenius phaeopus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Whimbrel | A10 | MTr | ||||

| N. p. phaeopus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Numenius tenuirostris Vieillot, 1817 | Slender-billed Curlew | B40 | 52 | ||||

| Numenius arquata (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Curlew | A12 | YMr | BCi | 1 | VP | 53 |

| N. a. arquata (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Limosa lapponica (Linnaeus, 1758) | Bar-tailed Godwit | A20 | MTi | ||||

| L. l. taymyrensis Engelmoer and Roselaar, 1998 | |||||||

| Limosa limosa (Linnaeus, 1758) | Black-tailed Godwit | A11 | MSr | BCr | 1 | VP | |

| L. l. limosa (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Arenaria interpres (Linnaeus, 1758) | Ruddy Turnstone | A20 | MTi | ||||

| A. i. interpres (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Calidris canutus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Red Knot | A20 | MTi | ||||

| C. c. canutus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Calidris pugnax (Linnaeus, 1758) | Ruff | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Calidris falcinellus (Pontoppidan, 1763) | Broad-billed Sandpiper | A30 | VA | ||||

| C. f. falcinellus (Pontoppidan, 1763) | |||||||

| Calidris ferruginea (Pontoppidan, 1763) | Curlew Sandpiper | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Calidris temminckii (Leisler, 1812) | Temminck’s Stint | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Calidris alba (Pallas, 1764) | Sanderling | A10 | MTr | ||||

| C. a. alba (Pallas, 1764) | |||||||

| Calidris alpina (Linnaeus, 1758) | Dunlin | A10 | MTr | ||||

| C. a. alpina (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Calidris maritima (Brünnich, 1764) | Purple Sandpiper | A30 | |||||

| Calidris minuta (Leisler, 1812) | Little Stint | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Calidris melanotos (Vieillot, 1819) | Pectoral Sandpiper | A30 | VA | ||||

| Limnodromus scolopaceus (Say, 1822) | Long-billed Dowitcher | A30 | 54 | ||||

| Scolopax rusticola Linnaeus, 1758 | Eurasian Woodcock | A12 | YMr | BCi | 1 | VP | 55 |

| Gallinago media (Latham, 1787) | Great Snipe | A20 | MTi | ||||

| Gallinago gallinago (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Snipe | A13 | MWr | 56 | |||

| G. g. gallinago (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Lymnocryptes minimus (Brünnich, 1764) | Jack Snipe | A10 | MWr | ||||

| Steganopus tricolor Vieillot, 1819 | Wilson’s Phalarope | A30 | |||||

| Phalaropus lobatus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Red-necked Phalarope | A30 | VA | ||||

| Phalaropus fulicarius (Linnaeus, 1758) | Red Phalarope | A30 | VA | ||||

| Actitis hypoleucos (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Sandpiper | A11 | YMr | BCr | 2− | UN | |

| Actitis macularius (Linnaeus, 1766) | Spotted Sandpiper | A30 | VA | ||||

| Tringa ochropus Linnaeus, 1758 | Green Sandpiper | A10 | YMr | ||||

| Tringa erythropus (Pallas, 1764) | Spotted Redshank | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Tringa nebularia (Gunnerus, 1767) | Common Greenshank | A10 | YMr | ||||

| Tringa totanus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Redshank | A12 | MSr | BCi | 1 | VP | 57 |

| T. t. totanus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Tringa glareola Linnaeus, 1758 | Wood Sandpiper | A10 | MSr | ||||

| Tringa stagnatilis (Bechstein, 1803) | Marsh Sandpiper | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Glareolidae | |||||||

| Cursorius cursor (Latham, 1787) | Cream-colored Courser | A30 | |||||

| C. c. cursor (Latham, 1787) | |||||||

| Glareola pratincola (Linnaeus, 1766) | Collared Pratincole | A20 | MTi | ||||

| G. p. pratincola (Linnaeus, 1766) | |||||||

| Laridae | |||||||

| Hydrocoloeus minutus (Pallas, 1776) | Little Gull | A10 | YMr | ||||

| Xema sabini (Sabine, 1819) | Sabine’s Gull | A30 | VA | ||||

| X. s. sabini (Sabine, 1819) | |||||||

| Rissa tridactyla (Linnaeus, 1758) | Black-legged Kittiwake | A20 | MTi | ||||

| R. t. tridactyla (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Larus genei Brème, 1839 | Slender-billed Gull | A30 | VA | ||||

| Larus ridibundus Linnaeus, 1766 | Black-headed Gull | A11 | YMr | BCr | 2= | UN | |

| Larus pipixcan Wagler, 1831 | Franklin’s Gull | A30 | VA | ||||

| Larus melanocephalus Temminck, 1820 | Mediterranean Gull | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Larus audouinii Payraudeau, 1826 | Audouin’s Gull | A30 | VA | ||||

| Larus canus Linnaeus, 1758 | Mew Gull | A10 | MWr | ||||

| L. c. canus Linnaeus, 1758 | A10 | MWr | |||||

| L. c. heinei Homeyer, 1853 | A30 | VA | |||||

| Larus fuscus Linnaeus, 1758 | Lesser Black-backed Gull | A10 | MWr | ||||

| L. f. graellsii A. E. Brehm, 1857 | A10 | MWr | |||||

| L. f. intermedius Schiøler, 1922 | A20 | MWi | |||||

| Larus argentatus Pontoppidan, 1763 | European Herring Gull | A20 | MWi | ||||

| L. a. argentatus Pontoppidan, 1763 | |||||||

| Larus michahellis J. F. Naumann, 1840 | Yellow-legged Gull | A11 | YMr | BCr | 2+ | AC | 58 |

| L. m. michahellis J. F. Naumann, 1840 | |||||||

| Larus cachinnans Pallas, 1811 | Caspian Gull | A10 | MWr | ||||

| Larus hyperboreus Gunnerus, 1767 | Glaucous Gull | A30 | VA | ||||

| L. h. hyperboreus Gunnerus, 1767 | |||||||

| Larus marinus Linnaeus, 1758 | Great Black-backed Gull | A30 | |||||

| Onychoprion fuscatus (Linnaeus, 1766) | Sooty Tern | B40 | 59 | ||||

| O. f. fuscatus (Linnaeus, 1766) | |||||||

| Sternula albifrons (Pallas, 1764) | Little Tern | A11 | MSr | BCr | 2− | VP | 60 |

| S. a. albifrons (Pallas, 1764) | |||||||

| Gelochelidon nilotica (J. F. Gmelin, 1789) | Common Gull-billed Tern | A10 | MTr | ||||

| G. n. nilotica (J. F. Gmelin, 1789) | |||||||

| Hydroprogne caspia (Pallas, 1770) | Caspian Tern | A20 | MTi | ||||

| Chlidonias hybrida (Pallas, 1811) | Whiskered Tern | A10 | MTr | ||||

| C. h. hybrida (Pallas, 1811) | |||||||

| Chlidonias leucopterus (Temminck, 1815) | White-winged Tern | A12 | MSr | BCi | 1 | VP | 61 |

| Chlidonias niger (Linnaeus, 1758) | Black Tern | A11 | MSr | BCr | 2− | VP | |

| C. n. niger (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Sterna hirundo Linnaeus, 1758 | Common Tern | A11 | MSr | BCr | 3− | PA | |

| S. h. hirundo Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Sterna paradisaea Pontoppidan, 1763 | Arctic Tern | A30 | 62 | ||||

| Thalasseus sandvicensis (Latham, 1787) | Sandwich Tern | A20 | VA | ||||

| T. s. sandvicensis (Latham, 1787) | |||||||

| Stercorariidae | |||||||

| Stercorarius longicaudus Vieillot, 1819 | Long-tailed Jaeger | A20 | MTi | ||||

| S. l. longicaudus Vieillot, 1819 | |||||||

| Stercorarius parasiticus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Arctic Jaeger | A20 | MTi | ||||

| Stercorarius pomarinus (Temminck, 1815) | Pomarine Jaeger | A30 | VA | ||||

| Catharacta skua Brünnich, 1764 | Great Skua | A30 | |||||

| Alcidae | |||||||

| Fratercula arctica (Linnaeus, 1758) | Atlantic Puffin | B40 | |||||

| Alca torda Linnaeus, 1758 | Razorbill | B40 | |||||

| A. t. islandica C. L. Brehm, 1831 | |||||||

| Uria aalge (Pontoppidan, 1763) | Common Murre | B40 | |||||

| U. a. aalge (Pontoppidan, 1763) | |||||||

| Strigiformes Tytonidae | |||||||

| Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769) | Common Barn Owl | A11 | YMr | BCr | 1 | VP | |

| T. a. alba (Scopoli, 1769) | A11 | YMr | BCr | 1 | VP | ||

| T. a. guttata (C. L. Brehm, 1831) | A30 | VA | |||||

| Strigidae | |||||||

| Glaucidium passerinum (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Pygmy Owl | A11 | YR | BCr | 3+ | PA | |

| G. p. passerinum (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Athene noctua (Scopoli, 1769) | Little Owl | A11 | YR | BCr | 4+ | AC | 63 |

| A. n. noctua (Scopoli, 1769) | |||||||

| Aegolius funereus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Boreal Owl | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3= | PA | |

| A. f. funereus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Otus scops (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Scops-Owl | A11 | MSr | BCr | 3+ | AC | |

| O. s. scops (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Asio otus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Northern Long-eared Owl | A11 | YMr | BCr | 4− | PA | |

| A. o. otus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Asio flammeus (Pontoppidan, 1763) | Short-eared Owl | A10 | MWr | ||||

| A. f. flammeus (Pontoppidan, 1763) | |||||||

| Strix aluco Linnaeus, 1758 | Tawny Owl | A11 | YR | BCr | 4+ | AC | |

| S. a. aluco Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Bubo bubo (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Eagle-Owl | A11 | YR | BCr | 2= | UN | |

| B. b. bubo (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Accipitriformes Pandionidae | |||||||

| Pandion haliaetus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Osprey | A10 | MTr | ||||

| P. h. haliaetus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Accipitridae | |||||||

| Elanus caeruleus (Desfontaines, 1789) | Black-winged Kite | A30 | VA | ||||

| E. c. caeruleus (Desfontaines, 1789) | |||||||

| Pernis apivorus (Linnaeus, 1758) | European Honey-buzzard | A11 | MSr | BCr | 3+ | AC | |

| Gypaetus barbatus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Bearded Vulture | BC11 | YR | BN | 1 | VP | 64 |

| G. b. barbatus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Neophron percnopterus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Egyptian Vulture | A20 | MTi | ||||

| N. p. percnopterus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Circaetus gallicus (J. F. Gmelin, 1788) | Short-toed Snake-eagle | A11 | MSr | BCr | 2+ | PA | |

| Gyps fulvus (Hablizl, 1783) | Griffon Vulture | AC10 | MSr | ||||

| G. f. fulvus (Hablizl, 1783) | |||||||

| Aegypius monachus (Linnaeus, 1766) | Cinereous Vulture | C10 | MSr | ||||

| Clanga pomarina (C. L. Brehm, 1831) | Lesser Spotted Eagle | A30 | VA | ||||

| Clanga clanga (Pallas, 1811) | Greater Spotted Eagle | A20 | MWi | ||||

| Aquila nipalensis Hodgson, 1833 | Tawny Eagle | B40 | |||||

| A. n. orientalis Cabanis, 1854 | |||||||

| Aquila heliaca Savigny, 1809 | Eastern Imperial Eagle | A30 | VA | ||||

| Aquila chrysaetos (Linnaeus, 1758) | Golden Eagle | A11 | YR | BCr | 3+ | AC | 65 |

| A. c. chrysaetos (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Aquila fasciata Vieillot, 1822 | Bonelli’s Eagle | A30 | VA | ||||

| A. f. fasciata Vieillot, 1822 | |||||||

| Hieraaetus pennatus (J. F. Gmelin, 1788) | Booted Eagle | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Circus aeruginosus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Western Marsh Harrier | A11 | YMr | BCr | 1 | VP | |

| C. a. aeruginosus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Circus cyaneus (Linnaeus, 1766) | Hen Harrier | A10 | MWr | ||||

| Circus macrourus (S. G. Gmelin, 1770) | Pallid Harrier | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Circus pygargus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Montagu’s Harrier | A12 | MSr | BCi | 1 | VP | 66 |

| Accipiter nisus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Sparrowhawk | A11 | YMr | BCr | 4+ | AC | |

| A. n. nisus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Accipiter gentilis (Linnaeus, 1758) | Northern Goshawk | A11 | YR | BCr | 3+ | AC | |

| A. g. gentilis (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Haliaeetus albicilla (Linnaeus, 1758) | White-tailed Eagle | A30 | VA | ||||

| Milvus milvus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Red Kite | A12 | YMr | BN | 1 | VP | 67 |

| M. m. milvus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Milvus migrans (Boddaert, 1783) | Black Kite | A11 | MSr | BCr | 2+ | PA | |

| M. m. migrans (Boddaert, 1783) | |||||||

| Buteo lagopus (Pontoppidan, 1763) | Rough-legged Buzzard | A20 | MWi | ||||

| B. l. lagopus (Pontoppidan, 1763) | |||||||

| Buteo buteo (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Buzzard | A11 | YMr | BCr | 4= | AC | |

| B. b. buteo (Linnaeus, 1758) | A11 | YMr | BCr | 4= | AC | ||

| B. b. vulpinus (Gloger, 1833) | A20 | MTi | |||||

| Buteo rufinus (Cretzschmar, 1829) | Long-legged Buzzard | A20 | MTi | ||||

| Bucerotiformes Upupidae | |||||||

| Upupa epops Linnaeus, 1758 | Common Hoopoe | A11 | MSr | BCr | 3= | AC | |

| U. e. epops Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Coraciiformes Meropidae | |||||||

| Merops persicus Pallas, 1773 | Blue-cheeked Bee-eater | A30 | |||||

| M. p. chrysocercus Cabanis and Heine, 1860 | A30 | VA | |||||

| M. p. persicus Pallas, 1773 | A30 | ||||||

| Merops apiaster Linnaeus, 1758 | European Bee-eater | A11 | MSr | BCr | 4+ | AC | |

| Coraciidae | |||||||

| Coracias garrulus Linnaeus, 1758 | European Roller | A11 | MSr | BCr | 1 | VP | |

| C. g. garrulus Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Alcedinidae | |||||||

| Alcedo atthis (Linnaeus, 1758) | Common Kingfisher | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3 | AC | 68 |

| A. a. ispida Linnaeus, 1758 | A20 | MWi | |||||

| A. a. atthis (Linnaeus, 1758) | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3 | AC | ||

| Piciformes Picidae | |||||||

| Jynx torquilla Linnaeus, 1758 | Eurasian Wryneck | A11 | MSr | BCr | 3− | PA | |

| J. t. torquilla Linnaeus, 1758 | A10 | MTr | |||||

| J. t. tschusii O. Kleinschmidt, 1907 | A11 | MSr | BCr | 3− | PA | ||

| Picus canus J. F. Gmelin, 1788 | Grey-faced Woodpecker | B40 | |||||

| P. c. canus J. F. Gmelin, 1788 | |||||||

| Picus viridis Linnaeus, 1758 | Eurasian Green Woodpecker | A11 | YR | BCr | 4= | AC | 69 |

| P. v. viridis Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Dryocopus martius (Linnaeus, 1758) | Black Woodpecker | A11 | YR | BCr | 3+ | AC | |

| D. m. martius (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Leiopicus medius (Linnaeus, 1758) | Middle Spotted Woodpecker | B40 | |||||

| L. m. medius (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Dryobates minor (Linnaeus, 1758) | Lesser Spotted Woodpecker | A11 | YR | BCr | 3+ | AC | |

| D. m. buturlini E. J. O. Hartert, 1912 | |||||||

| Dendrocopos leucotos (Bechstein, 1802) | White-backed Woodpecker | B40 | |||||

| D. l. lilfordi (Sharpe and Dresser, 1871) | |||||||

| Dendrocopos major (Linnaeus, 1758) | Great Spotted Woodpecker | A11 | YR | BCr | 5+ | AC | |

| D. m. pinetorum (C. L. Brehm, 1831) | |||||||

| Falconiformes Falconidae | |||||||

| Falco naumanni Fleischer, 1818 | Lesser Kestrel | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Falco tinnunculus Linnaeus, 1758 | Common Kestrel | A11 | YMr | BCr | 4= | AC | |

| F. t. tinnunculus Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Falco vespertinus Linnaeus, 1766 | Red-footed Falcon | A10 | MTr | ||||

| Falco eleonorae Gené, 1839 | Eleonora’s Falcon | A10 | MTi | ||||

| Falco columbarius Linnaeus, 1758 | Merlin | A10 | MWr | ||||

| F. c. aesalon Tunstall, 1771 | |||||||

| Falco subbuteo Linnaeus, 1758 | Eurasian Hobby | A11 | MSr | BCr | 3+ | AC | |

| F. s. subbuteo Linnaeus, 1758 | |||||||

| Falco biarmicus Temminck, 1825 | Lanner Falcon | AD30 | VA | 70 | |||

| F. b. feldeggii Schlegel, 1843 | |||||||

| Falco cherrug J. E. Gray, 1834 | Saker Falcon | AD30 | VA | 71 | |||

| F. c. cherrug J. E. Gray, 1834 | |||||||

| Falco peregrinus Tunstall, 1771 | Peregrine Falcon | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3+ | AC | 72 |

| F. p. calidus Latham, 1790 | A20 | MWi | |||||

| F. p. peregrinus Tunstall, 1771 | A11 | YMr | BCr | 3+ | AC | ||

| Psittaciformes Psittacidae | |||||||

| Myiopsitta monachus (Boddaert, 1783) | Monk Parakeet | E12 | YR | BCi | 1 | 73 | |

| M. m. monachus (Boddaert, 1783) | |||||||

| Passeriformes Oriolidae | |||||||

| Oriolus oriolus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Golden Oriole | A11 | MSr | BCr | 4= | AC | |

| Laniidae | |||||||

| Lanius collurio Linnaeus, 1758 | Red-backed Shrike | A11 | MSr | BCr | 4− | PA | |

| Lanius minor J. F. Gmelin, 1788 | Lesser Grey Shrike | A24 | MSi | BP | 0 | VY | 74 |

| L. m. minor J. F. Gmelin, 1788 | |||||||

| Lanius excubitor Linnaeus, 1758 | Great Grey Shrike | A10 | MWr | 75 | |||

| L. e. excubitor Linnaeus, 1758 | A10 | MWr | |||||

| L. e. homeyeri Cabanis, 1873 | B40 | ||||||

| Lanius meridionalis Temminck, 1820 | Southern Grey Shrike | A30 | |||||

| Lanius senator Linnaeus, 1758 | Woodchat Shrike | A14 | MSr | BP | 0 | VY | 76 |

| L. s. senator Linnaeus, 1758 | A14 | MSr | BP | 0 | VY | ||

| L. s. niloticus (Bonaparte, 1853) | B40 | ||||||

| L. s. badius Hartlaub, 1854 | A30 | ||||||

| Corvidae | |||||||

| Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax (Linnaeus, 1758) | Red-billed Chough | A11 | YR | BCr | 3= | AC | |

| P. p. erythroramphos (Vieillot, 1817) | |||||||

| Pyrrhocorax graculus (Linnaeus, 1766) | Yellow-billed Chough | A11 | YR | BCr | 4= | AC | |

| P. g. graculus (Linnaeus, 1766) | |||||||

| Garrulus glandarius (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Jay | A11 | YMr | BCr | 5+ | AC | 77 |

| G. g. glandarius (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||

| Pica pica (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eurasian Magpie | A11 | YR | BCr | 6+ | AC | |

| P. p. pica (Linnaeus, 1758) | |||||||