Characterization of Laser Cleaning of Artworks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Influence of environment

- -

- hydrocarbons, emitted during non-complete combustion of oil-derivative products,

- -

- carbon monoxide, constituting around 2/3 of all volatile poisons originating from motor exhaust fumes,

- -

- nitrogen and sulphur oxides (SO2 - dozens of millions tons per year in Europe).

- -

- darkening of stone surface and conversion into calcium sulphate,

- -

- swelling of top layers,

- -

- shattering of superficial layers and further, deeper degradation,

- -

- dump absorption (acid rains) in uncovered, fresh subsequent layer.

3. Diagnostics of art works

3.1 Non-destructive, physico-chemical and structural methods of analysis of monuments and works of art

- identification of molecular compounds created at the artwork surface,

- studies of composition of painting layers,

- identification of fibers material, chemical composition and soiling of paper and parchment,

- investigations of epoxy resins.

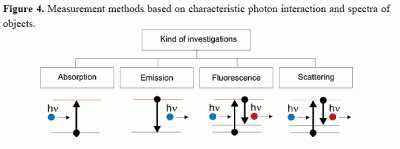

3.2 Laser methods

3.2.1. Laser induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) and Raman spectroscopy

3.2.2. Optical Coherent Tomography (OCT)

- -

- qualitative: the shape of craters (surface map) is recovered, additionally (SEM) images were made to compare to the surface maps generated from volume OCT data (Figure 16a,c, 17a),

- -

- quantitative: the depths of the ablation craters are measured using OCT data (Figure 16b, 17b).

3.2.3. Laser interferometry

3.3. Optical and physical methods

3.3.1. Thermography

3.3.2. Analysis of light diffuse reflection coefficient

3.3.3. Color measurements (colorimetry)

3.3.4. Analysis of acoustic wave amplitude

3.3.5. Analyses of surface damage thresholds and roughness

4. Exploitation of the results, conclusions

- conservation and laser restoration of internal décor of Sigismund Chapel at Wawel Hill in Cracow, about 800 m2 of decorative sculptor's surfaces,

- conservation and laser cleaning of walls and decoration elements in Arch-Collegiate Church in Tum, near Łęczyca, including ancient Romanesque sculpture of Christ Pantokrator,

- cleaning of elements of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Warsaw,

- restoration of epitaph and stall of King's Batory Chapel at Wawel Hill in Cracow,

- cleaning of St. Blaise sculpture in Dubrovnik, Croatia,

- restoration of tombstone of Juliusz Słowacki and tombs of national government members “Avenue des Polonaise” at Montmartre Cemetery in Paris,

- cleaning of marble sculpture of Henryk Lubomirski in Łańcut (Antonio Canova, 1794).

Acknowledgments

- EUREKA E!2542 RENOVA LASER “Laser renovation of monuments and art works” (grant No 217/E-284/SPUB-M/EUREKA/T-11/DZ 203/2001-2003),

- COST, G7 Action, “Laser cleaning of modern works of art”(grant No 125/E-323/SPB/COST/H-1/DWM 85/2004-2005),

- COST, G8 Action, “Complex set of non-destructive optoelectronic diagnostics for testing and conservation of museum objects in Poland” (grant No 120/E-410/SPB/COST/T-11/DWM 726/2003-2005)

- EUREKA E!3843 EULASNET LASCAN “Advanced laser cleaning of old paintings, paper, parchment and metal objects” (grant No 120/E-410/SPB/EUREKA/KG/DWM 97/2005-2007).

References and Notes

- Asmus, J.F.; Murphy, C.G.; Munk, W.H. Studies on the Interaction of Laser Radiation with Art. Artifacts. Proc. SPIE 1973, 41, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Asmus, J.F. Lasers clean delicate art works. Laser Focus 1976, 12, 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M. Laser cleaning in conservation: an Introduction; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hildenhagen, J.; Dickmann, K. Nd: YAG Laser with Wavelengths from IR to UV (ω, 2ω, 3ω, 4ω) and Corresponding Applications in Conservation of Various Artworks. Abstract Book. LACONA IV, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Paris, France, Sept. 11-14 2001; pp. 273–276.

- Agnani, A.; Esposito, E. Scanning Laser Doppler Vibrometry Application to Artworks: New Acoustic and Mechanical Exciters for Structural Diagnostics. Springer Proceedings in Physics, Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA V, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Osnabrück, Germany, Sept. 15-18, 2003; 100, pp. 499–504.

- Ostrowski, R.; Marczak, J.; Strzelec, M.; Barcikowski, S.; Walter, J.; Ostendorf, A. Health risks caused by particulate emission during laser cleaning. Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks LACONA VI Proceedings, Vienna, Austria, Sept. 21--25, 2005; Nimmrichter, J., Kautek, W., Schreiner, M., Eds.; Springer Proc. in Physics. 116, pp. 623–630.

- Koss, A.; Marczak, J. Application of lasers in conservation of monuments and works of art. POLLASNET: Laser cleaning. http://www.pollasnet.org.pl/zdj/2_LASER_CLEANING.pdf (accessed Oct 19, 2008).

- Koss, A.; Marczak, J.; Strzelec, M. Experimental investigations and removal of encrustations from interior stone decorations of King Sigismunds's Chapel at Wawel Castle in Cracow. Springer Proceedings in Physics, Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA VI, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Vienna, Austria, Sept. 21-25, 2005; 116, pp. 125–132.

- Koss, A.; Marczak, J.; Strzelec, M. Arch-collegiate church in Tum – laser renovation of priceless architectural decorations. Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA VII, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Madrid, Spain, Sept. 17-21, 2007.

- Reitz, W. Surface cleaning and coating removal with lasers. In Lasers in Surface Engineering (Surface Engineering Series); Dahotre, N.B., Sudarshan, T.S., Eds.; ASM International: Cleveland, USA, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 431–464. [Google Scholar]

- Kapsalas, P.; Maravelaki-Kalaitzaki, P.; Zervakis, M.; Delegou, E.T.; Moropoulou, A. Optical inspection for quantification of decay on stone surfaces. NDT&E Int. 2007, 40, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Salimbeni, R.; Pini, R.; Siano, S.; Calcagno, G. Assessment of the state of conservation of stone artworks after laser cleaning: comparison with conventional cleaning results on a two-decade follow up. J. Cult. Herit. 2000, 1, 385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Cassar, M.; Bordass, B.; Oreszczyn, T.; Blades, N. Guidelines on pollution control in heritage buildings. Technical report; In Museum Pract.; (Suppl.), London, UK, Nov 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sarzyński, A.; Skrzeczanowski, W.; Marczak, J. Colorimetry, LIBS and Raman experiments on renaissance green sandstone decorations during laser clearing of King Sigismund's Chapel in Wawel Castle, Cracow, Poland. Springer Proceedings in Physics, Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA VI, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Vienna, Austria, Sept. 21-25, 2005; 116, pp. 355–360.

- Anglos, D. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy in Art and Archaeology. Appl. Spectrosc. 2001, 55, 186A–205A. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Gregory D.; Clark, Robin J.H. Raman microscopy in archaeological science. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2004, 31, 1137–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Tornari, V. Laser interference-based techniques and applications in structural inspection of works of art. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 761–780. [Google Scholar]

- Castellini, P.; Esposito, E.; Marchetti, B.; Paone, N.; Tomasini, E.P. New applications of Scanning Laser Doppler Vibrometry (SLDV) to non-destructive diagnostics of artworks: mosaics, ceramics, inlaid wood and easel painting. J. Cult. Herit. 2004, 4 (Suppl.1), 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Sarzyński, A.; Jach, K.; Marczak, J. Comparison of Wet and Dry laser Cleaning of Artworks. Springer Proceedings in Physics, Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA VI, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Vienna, Austria, Sept. 21-25, 2005; 116, pp. 161–167.

- Góra, M.; Targowski, P.; Rycyk, A.; Marczak, M. Varnish Ablation Control by Optical Coherence Tomography. Laser Chem. 2006, 2006, 10647. [Google Scholar]

- Góra, M.; Rycyk, A.; Marczak, J.; Targowski, P.; Kowalczyk, A. From medical to art diagnostics OCT: a novel tool for varnish ablation control. Proc. SPIE 2007, 6429, 64292V–1. [Google Scholar]

- de Cruz, A.; Wolbarsht, M.L.; Hauger, S.A. Laser removal of contaminants from painted surfaces. J. Cult. Herit. 2000, 1 (Suppl.1), 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Tornari, V.; Zafiropulos, V.; Bonarou, A.; Vainos, N.A.; Fotakis, C. Modern technology in artwork conservation: a laser-based approach for process control and evaluation. J. Opt. Las. Eng. 2000, 34, 309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Tornari, V. Laser Interference-Based Techniques and Applications in Structural Inspection of Works of Art. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 761–80. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelec, M.; Marczak, J. Interferometric measurements of acoustic waves generated during laser cleaning of works of art. Proc. SPIE 2001, 4402, 235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Avdelidis, N.P.; Moropoulou, A. Applications of infrared thermography for the investigation of historic structures. J. Cult. Herit. 2004, 5, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, J.; Koss, A.; Pręgowski, P. Thermal Effects on Artwork Surface Cleaned with Laser Ablation Method. Proc. SPIE 2003, 5146, 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, J.; Koss, A.; Pręgowski, P. Study of Thermal Effects on Artwork Surfaces Cleaned with Laser Ablation Method. Proc. SPIE 2003, 5073, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, J. Surface cleaning of art work by UV, VIS and IR pulse laser radiation. Proc. SPIE 2001, 4402, 202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Berger-Shunn, A. Practical Color Measurement: A Primer for the Beginner, A Reminder for the Expert; Wiley Series in Pure and Applied Optics; Wiley-Interscience - John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Heras, M.; Alvarez de Buergo, M.; Esther Rebollar, E.; Oujja, M.; Castillejo, M.; Fort, R. Laser removal of water repellent treatments on limestone. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2003, 219, 290–299. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, J.; Strzelec, M.; Koss, A. Laser cleaning of the interior stone decoration of King Sigismund's Chapel at Wawel Castle in Cracow. Proc. SPIE 2005, 5958, 595808. [Google Scholar]

- Strlic, M.; Selih, V.S.; Kolar, J.; Kocar, D.; Pihlar, B.; Ostrowski, R.; Marczak, J.; Strzelec, M.; Marincek, M.; Vuorinen, T.; Johansson, L.S. Optimisation and on-line acoustic monitoring of laser cleaning of soiled paper. Appl. Phys. A – Mater. 2005, A81, 943–951. [Google Scholar]

- Salimbeni, R.; Pini, R.; Siano, S. “Achievement of optimum laser cleaning in the restoration of artworks: expected improvements by on-line optical diagnostics. Spectrochim. Acta B 2001, B56, 877–885. [Google Scholar]

- Jezersek, M.; Milanic, M.; Babnik, A.; Mozina, J. Real-time optodynamic monitoring of pulsed laser decoating rate. Ultrasonics 2004, 42, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, J. Military University of Technology: Warsaw, Poland; Unpublished experimental results obtained in the frames of EUREKA E!2542 RENOVA LASER project; 2001-2003. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelec, M.; Marczak, J.; Ostrowski, R.; Koss, A.; Szambelan, R. Results of Nd:YAG laser renovation of decorative ivory jug. Springer Proceedings in Physics, Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA V, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Osnabrück, Germany, Sept. 15-18, 2003; 100, pp. 163–168.

- Ostrowski, R.; Marczak, J.; Strzelec, M.; Koss, A. Laser damage thresholds of bone objects. Proc. SPIE 2008, 6618. in print. [Google Scholar]

- Koss, A.; Dreścik, D.; Marczak, J.; Ostrowski, R.; Rycyk, A.; Strzelec, M. Laser cleaning of set of 18thcentury ivory statues of Twelve Apostles. Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA VII, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Madrid, Spain, Sept. 17-21, 2007.

- Gaspar, P.; Hubbard, Ch.; McPhail, D.; Cummings, A. A topographical assessment and comparison of conservation cleaning treatments. J. Cult. Her. 2003, 4, 294s–302s. [Google Scholar]

- Maravelaki, P.V.; Zafiropulos, V.; Kilikoglou, V.; Kailaitzaki, M.; Fotakis, C. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy as a diagnostic technique for the laser cleaning of marble. Spectrochim. Acta B 1997, 52, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Borgia, I.; Burgio, L.M.F.; Corsi, M.; Fantoni, R.; Palleschi, V.; Salvetti, A.; Squarcialupi, M.C.; Tognoni, E. Self-calibrated quantitative elemental analysis by laser induced plasma spectroscopy: application to pigment analysis. J. Cult. Herit. 2000, 1, S281–S286. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.J.H. Pigment identification by spectroscopic means: an arts/science interface. C.R.Chimie 2002, 5, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, I.R.; Griffiths, R. Raman spectrometry with fiber-optic sampling. Appl. Spectr. 1996, 50, 12A–30A. [Google Scholar]

- Burgio, L.; Clark, Robin J.H. Library of FT-Raman spectra of pigments, minerals, pigment media and varnishes, and supplement to existing library of Raman spectra of pigments with visible excitation. Spectrochim. Acta A 2001, 57, 1491–1521. [Google Scholar]

- Targowski, P.; Rouba, B.; Wojtkowski, M.; Kowalczyk, A. The application of optical coherence tomography to non-destructive examination of museum objects. Stud. Cons. 2004, 49, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.-L.; Lu, C.-W.; Hsu, I.-J.; Yang, C.C. The use of optical coherence tomography for monitoring the subsurface morphologies of archaic jades. Archaeometry 2004, 46, 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Gora, M.; Pircher, M.; Goetzinger, E.; Bajraszewski, T.; Strlic, M.; Kolar, J.; Hitzenberger, C.K.; Targowski, P. Optical coherence tomography for examination of parchment degradation. Laser Chem. 2006, 68, 679. [Google Scholar]

- 2006-2009 Leverhulme Trust Research Project Grant. Application of a new non-invasive technique (OCT) to paintings conservation. http://www.leverhulme.ac.uk/.

- Esposito, E.; Scalise, L.; Tornari, V. Measurement of stress waves in polymers generated by UV laser ablation. Opt. Laser Eng. 2002, 38, 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Teule, R.; Scholten, H.; Van den Brink, O.F.; Heeren, R.M.A.; Zafiropulos, V.; Hesterman, R.; Castillejo, M.; Martín, M.; Ullenius, U.; Larsson, I.; Guerra-Librero, F.; Silva, A.; Gouveia, H.; Albuquerque, M-B. Controlled UV laser cleaning of painted artworks: a systematic effect study on egg tempera paint samples. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 209s–215s. [Google Scholar]

- Remondino, F. Digital preservation, documentation and analysis of heritage with active and passive sensors. Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA VII, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Madrid, Spain, Sept. 17-21, 2007.

- Siano, S.; Casciani, A.; Giusti, A.; Matteini, M.; Pini, R.; Porcinai, S.; Salimbeni, R. The Santi Quattro Coronati by Nanni di Banco: cleaning of the gilded decorations. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, M.; Casini, A.; Cucci, C.; Picollo, M.; Radicati, B.; Vervat, M. Non-invasive spectroscopic measurements on the Il ritratto della figliastra by Giovanni Fattori: identification of pigments and colourimetric analysis. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, A.; Fischer, C.; Watkins, K.G.; Glasmacher, M.; Kheyrandish, H.; Brown, A.; Steen, W.M.; Beahanet, P. Laser removal of oxides from a copper substrate using Q-switched Nd:YAG radiation at 1064 nm, 532 nm and 266 nm. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1998, 127–129, 773–780. [Google Scholar]

- Grassi, S.; Carretti, E.; Pecorelli, P.; Iacopini, F.; Baglioni, P.; Dei, L. The conservation of the Vecchietta's wall paintings in the Old Sacristy of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena: The use of nanotechnological cleaning agents. J. Cult. Herit. 2007, 8, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Castillejo, M.; Martín, M.; Oujja, M.; Santamaría, J.; Silva, D.; Torres, R.; Manousaki, A.; Zafiropulos, V.; Van den Brink, O.F.; Heeren, M.R.A.; Teule, R.; Silva, A. Evaluation of the chemical and physical changes induced by KrF laser irradiation of tempera paints. J. Cult. Herit. 2004, 4, 257s–263s. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Herasa, M.; Alvarez de Buergoa, M.; Rebollar, E.; Oujja, M.; Castillejo, M.; Fort, R. Laser removal of water repellent treatments on limestone. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2003, 219, 290–299. [Google Scholar]

- Vergeès Belmin, V. Towards a definition of common evaluation criteria for the cleaning of porous buildings materials: a review. Sci. Technol. Cult. Herit. 1996, 5, 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, J.; Jach, K.; Sarzynski, A. Numerical modelling of laser cleaning and conservation of artworks. Springer Proceedings in Physics, Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA V, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Osnabrück, Germany, Sept. 15-18, 2003; 100, pp. 319–326.

- Marczak, J.; Jach, K.; Sarzyński, A. Improvement in encrustation removal from artworks using multipulse Q-switched laser. Proc. SPIE. 2005, 5958, 59582G. [Google Scholar]

- Sarzyński, A.; Jach, K.; Marczak, J. Comparison of wet and dry laser clearing of artworks. Springer Proceedings in Physics, Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA VI, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks; 116, pp. 161–168.

- Marczak, J.; Koss, A.; Strzelec, M.; Ostrowski, R.; Sarzynski, A.; Strlic, M.; Kolar, J.; Fenic, C.; Necsoiu, T.; Caramizoiu, A.; Barcikowski, S. Laser cleaning of art works - experiments and numerical model. Rom. J. Optoel. 2005, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, J.; Jach, K.; Ostrowski, R.; Sarzynski, A. Experimental and theoretical indications on laser cleaning. Springer Proceedings in Physics, Proceedings of the International Conference LACONA V, Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks, Osnabrück, Germany, Sept. 15-18 2003; 100, pp. 103–112.

- Ostrowski, R.; Marczak, J.; Jach, K.; Sarzyński, A. Selection of radiation parameters of lasers used for artwork conservation. Proc SPIE 2003, 5146, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

| Pollutant | Source | Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Sulphur dioxide (SO2) | Combustion of fossil fuels, mainly coal |

|

| Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) | Motor exhaust gases, combustion in stoves, boilers, in industrial processes, decomposition of cellulose, photochemical reaction of other NOx |

|

| Ozone (O3) | Photocopiers, laser printers, electrostatic particles filters, photochemical reactions |

|

| Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) | Motor exhaust gases (catalytic converters), natural geochemical processes, vulcanized rubber, waterlogged organic materials |

|

| Carbonyls (formic acid, formaldehyde, acetic acid, C=O) | Drying paint, wood and wooden products, cellulose decomposition, resins, thermoplastics |

|

| Solid particles | Traffic, abrasion, pollens, combustion, insects, salts |

|

| DIAGNOSTIC METHOD |

|---|

OBJECT STRUCTURE

|

| Gotlandic sandstone | |||||||||

| Square No | Laser fluence [J/cm2] | L* | a* | b* |  | ||||

| 1 | 0.24 | 35.48 | 0.96 | 8.16 | |||||

| 2 | 0.36 | 38.12 | 0.92 | 8.98 | |||||

| 3 | 0.42 | 39.22 | 0.88 | 8.72 | |||||

| 4 | 0.50 | 42.11 | 1.02 | 9.03 | |||||

| 5 | 0.62 | 43.26 | 0.76 | 8.42 | |||||

| 6 | 0.80 | 44.32 | 2.14 | 14.12 | |||||

| 7 | 1.10 | 46.82 | 2.18 | 15.32 | |||||

| 8 | 1.42 | 50.64 | 2.26 | 15.94 | |||||

| 9 | 1.78 | 53.76 | 1.65 | 14.72 | |||||

| 10 | 2.10 | 58.39 | 1.25 | 15.76 | |||||

| The King's Batory Chapel – throne wall, sculpture of angel (limestone from Pińczów, Poland) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.32 | 60.36 | 3.52 | 16 |  | ||||

| 2 | 0.45 | 63.05 | 3.99 | 17.78 | |||||

| 3 | 0.68 | 68.31 | 3.69 | 17.63 | |||||

| 4 | 1.10 | 72.28 | 3.34 | 17.48 | |||||

| 5 | 1.43 | 74.66 | 3.28 | 17.81 | |||||

| 6 | 1.78 | 78.24 | 2.74 | 17.88 | |||||

| 7 | 2.15 | 81.22 | 2.12 | 15.40 | |||||

| The King's Batory Chapel – throne wall, window frame (Szydłowicki sandstone, Poland) | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.24 | 42.62 | 2.21 | 12.73 |  | ||||

| 2 | 0.36 | 47.11 | 2.52 | 13.99 | |||||

| 3 | 0.42 | 48.06 | 2.96 | 16.20 | |||||

| 4 | 0.50 | 50.20 | 2.28 | 14.38 | |||||

| 5 | 0.62 | 53.66 | 3.01 | 15.81 | |||||

| 6 | 0.80 | 55.45 | 2.61 | 16.41 | |||||

| 7 | 1.10 | 59.56 | 2.89 | 19.08 | |||||

| 8 | 1.42 | 59.80 | 2.08 | 16.82 | |||||

| 9 | 1.78 | 60.02 | 2.08 | 16.53 | |||||

| 10 | 2.10 | 59.85 | 1.05 | 14.66 | |||||

| Sample | Photograph | Damage threshold for single laser pulse [J/cm2] | Damage threshold for 10 Hz repetition frequency [J/cm2] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,064 nm | 532 nm | 335 nm | 1,064 nm | 532 nm | 335 nm | ||

| “white” bovine rib |  | 4.9 | 7.7 | 1 | 4.0 | 8.6 | < 1.5 |

| “brown” bovine rib |  | 5.2 | 8.6 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 8.6 | 1 |

| ivory (sample 1) |  | >20 | 18.6 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 0.9 |

| ivory (sample 2) |  | - | ≫ 9 | - | - | 3.5 | 0.9 |

| bovine horn |  | - | 8 | - | - | 4.8 | - |

| boar tusk |  | - | > 16 | - | - | - | - |

| bovine tibia |  | - | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Magmaticrock “Gobro” | Crystalline marble 1 | Carrara marble 1 | Alabaster | Crystalline marble 2 | Carrara marble 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R[Å] | RC[%] | R[Å] | RC[%] | R[Å] | RC[%] | R[Å] | RC[%] | R[Å] | RC[%] | R[Å] | RC[%] |

| 199.9 | 6.35 | 927.2 | 7.01 | 856.5 | 6.97 | 388.2 | 5.78 | 554.6 | 6.57 | 847.7 | 6.22 |

© 2008 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Marczak, J.; Koss, A.; Targowski, P.; Góra, M.; Strzelec, M.; Sarzyński, A.; Skrzeczanowski, W.; Ostrowski, R.; Rycyk, A. Characterization of Laser Cleaning of Artworks. Sensors 2008, 8, 6507-6548. https://doi.org/10.3390/s8106507

Marczak J, Koss A, Targowski P, Góra M, Strzelec M, Sarzyński A, Skrzeczanowski W, Ostrowski R, Rycyk A. Characterization of Laser Cleaning of Artworks. Sensors. 2008; 8(10):6507-6548. https://doi.org/10.3390/s8106507

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarczak, Jan, Andrzej Koss, Piotr Targowski, Michalina Góra, Marek Strzelec, Antoni Sarzyński, Wojciech Skrzeczanowski, Roman Ostrowski, and Antoni Rycyk. 2008. "Characterization of Laser Cleaning of Artworks" Sensors 8, no. 10: 6507-6548. https://doi.org/10.3390/s8106507

APA StyleMarczak, J., Koss, A., Targowski, P., Góra, M., Strzelec, M., Sarzyński, A., Skrzeczanowski, W., Ostrowski, R., & Rycyk, A. (2008). Characterization of Laser Cleaning of Artworks. Sensors, 8(10), 6507-6548. https://doi.org/10.3390/s8106507