Moisture Influence on the Thermal Operation of the Late 19th Century Brick Facade, in a Historic Building in the City of Zamora

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Characterization of Materials

- λn

- thermal conductivity of the material conditions n, W(m.K);

- Fm

- moisture conversion factor;

- FT

- temperature conversión factor;

- Fa

- ageing conversión factor.

- fψ

- design moisture coefficient % by volumen;

- ψdesign

- design water content % by volumen (m3/m3).

2.2. “in situ” Thermal Flow Test

- Heat flow meter AMR model FQAD19T of Ahlborn (250 mm × 250 mm × 1.5 mm) made of epoxy resin (Figure 2a) (accuracy 0.02% of the measured value) suitable for flat plaster finish, which was placed inside, and a heat flow meter AMR model FQAD18TSI of Ahlborn (120 mm × 120 mm × 3 mm) made of silicon (Figure 2b), which adapts well to the most irregular surface of the brick facade (accuracy 0.02% of the measured value of the measured value).

- Four thermocouples (Figure 2b) to measure the surface temperature: indoor and outdoor, and the temperature: outdoor and indoor (accuracy ± 0.05 °C ± 0.05% of the measured value).

- For data storage of heat fluxes and surface temperatures, two Data Logger units model Almemo 2590 of the Ahlborn trademark (Figure 2d) (accuracy 0.03%) have been used.

- FLIR ThermaCAM B29 brand thermal imager, with a thermal sensitivity of 0.1 °C, temperature measurement range from −20 °C to + 100 °C, spectrum range of 7.5 to 13 μm, and emissivity value of the brick 0.9.

- Λ

- thermal conductance, en W/(m2.K)

- q

- density of heat flow rate = Ф/A, en W/m2;

- Tsi

- interior surface temperature, en °C;

- Tse

- exterior surface temperature, en °C.

2.3. Energy Simulations Based on the Data Obtained in the Flow Test

- The first simulation has been carried out for an alleged case of rainwater that moistens the facade. According to document DB HS1 of the Technical Building Code (Spain) [31], a wall of the thickness of the brick stretcher is sufficient to prevent the passage of rainwater into the interior; for this reason, it has been simulated that only the leaf is moistened on the exterior and is done so gradually: 1/3 of the thickness is totally wetted 241 l/m3 and has a λ = 1.96 W/(mK), another third of the facade is wetted at 66% 160 l/m3 with λ = 1. 52 W/(m.K), and the remaining third is moistened to 33%, 80 l/m3 with λ = 1.08 W/(m.K).

- The second simulation was carried out assuming that it is a boundary zone where the water rises by capillarity and it has been assumed that the two brick leafs were similarly moistened. For a water content of 0.015 m3/m3 (lthe facade is practically dry), λ pressed brick = 0.73 W/(m.K), λ ordinary brick = 0.74 W/(m.K), and λ mortar = 0.73 W/(m.K). For a water content of 0.077 m3/m3, λ pressed brick = 1.07 W/(m.K), λ ordinary brick = 1.07 W/(m.K), and λ mortar = 1.11 W/(m.K). For a water content of 0.125 m3/m3, λ pressed brick = 1.33 W/(m.K), λ ordinary brick = 1.31 W/(m.K), and λ mortar = 1.40 W/(m.K). For a water content of 0.165 m3/m3, λ pressed brick = 1.54 W/(m.K), λ ordinary brick = 1.52 W/(m.K), and λ mortar = 1.65 W/(m.K). For a water content of 0.210 m3/m3, λ pressed brick = 1.79 W/(m.K), λ ordinary brick = 1.79 W/(m.K), and λ mortar = 1.795 W/(m.K), and for a water content of 0.241 m3/m3, the values previously calculated. Then, other simulations have been carried out to relate the water content of this facade with the thermal flux that would pass through it, the value of the thermal conductance and the thickness of a leaf of insulating material that would be necessary, located inside, to maintain the dry values: flow and thermal conductance of the facade, depending on the water content.

3. Results

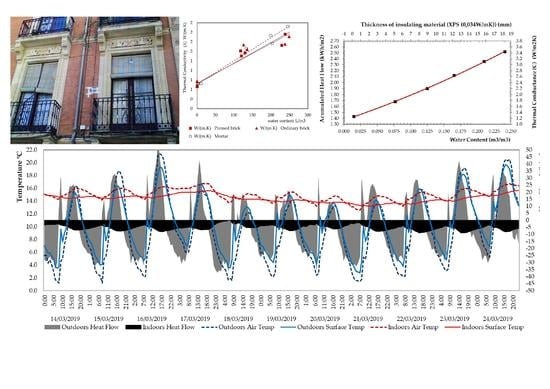

3.1. Materials Characterization

3.2. Thermal Flow Test

3.3. Simulations

3.3.1. Simulations of the Behavior of the Facade in the Conditions of the Test “in situ”

3.3.2. Simulations of Facade Behavior in Other Humidity Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Directiva 2012/27/UE del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo de 25 de octubre de 2012 relativa a la eficiencia energética, por la que se modifican las Directivas 2009/125/CE y 2010/30/UE, y por la que se derogan las Directivas 2004/8/CE y 2006/32/CE. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02012L0027-20180709&from=EN (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Calzolari, M. Prestazione Energetica delle Architetture Storiche: Sfide e Soluzioni; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Belpoliti, V.; Bizzarri, G.; Boarin, P.; Calzolari, M.; Davoli, P. A parametric method to assess the energy performance of historical urban settlements. Evaluation of the current energy performance and simulation of retrofit strategies for an Italian case study. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 30, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litti, G.; Khoshdel, S.; Audenaert, A.; Braet, J. Hygrothermal performance evaluation of traditional brick masonry in historic buildings. Energy Build. 2015, 105, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Cui, Y.; Shao, Y.; Han, F. Simulation Research on the Effect of Coupled Heat and Moisture Transfer on the Energy Consumption and Indoor Environment of Public Buildings. Energies 2019, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pavlík, Z.; Fiala, L.; Vejmelková, E.; Černý, R. Application of effective media theory for determination of thermal properties of hollow bricks as a function of moisture content. Int. J. Thermophys. 2013, 34, 894–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degiovanni, A.; Moyne, C. Conductivité thermique de matériaux poreux humides: Évaluation théorique et possibilité de mesure. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1987, 30, 2225–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Moyne, C.; Degiovanni, A. Approche expérimentale et théorique de la conductivité thermique des milieux poreux humides—I. Expérimentation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1988, 31, 2305–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, H.; Jannot, Y.; Gaye, S.; Demeurie, F. Measurement and modelisation of the thermal conductivity of a wet composite porous medium: Laterite based bricks with millet waste additive. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 41, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vololonirina, O.; Coutand, M.; Perrin, B. Characterization of hygrothermal properties of wood-based products–Impact of moisture content and temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camino-Olea, M.S.; Cabeza-Prieto, A.; Llorente-Alvarez, A.; Sáez-Pérez, M.P.; Rodríguez-Esteban, M.A. Brick Walls of Buildings of the Historical Heritage. Comparative Analysis of the Thermal Conductivity in Dry and Saturated State. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 082059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bella, J.M.; Dominguez-Hernandez, J.; Cano-Suñén, E.; del Coz-Diaz, J.J.; Rabanal, F.P.Á. A correction factor to approximate the design thermal conductivity of building materials. Appl. Span. Facades. Energy Build. 2015, 88, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Esteban, M.A. La Arquitectura de Ladrillo y su Construcción en la Ciudad de Zamora (1888–1931). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ten, J.G.; Orts, M.J.; Saburit, A.; Silva, G. Thermal conductivity of traditional ceramics. Part I: Influence of bulk density and firing temperature. Ceram. Int. 1951, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Esteban, M.A. La Arquitectura de Ladrillo y su Construcción en la Ciudad de Zamora (1888–1931); Instituto de Estudios Zamoranos Floríán de Ocampo: Zamora, Spain, 2014; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Esteban, M.A.; Camino-Olea, M.S.; Sáez-Pérez, M.P. El ladrillo en la arquitectura ecléctica y modernista de la ciudad de Zamora: Análisis de los tipos, los aparejos y la ejecución de los muros. Informes de la Construcción 2014, 66, e035. Available online: http://informesdelaconstruccion.revistas.csic.es/index.php/informesdelaconstruccion/article/view/3488/3926 (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- European Standard EN 772-21 Methods of test for masonry units. Part 21: Determination of water absorption of clay and calcium silicate masonry units by cold water absorption. 2011; AENOR. [Google Scholar]

- Dondi, M.; Mazzanti, F.; Principi, P.; Raimondo, M.; Zanarini, G. Thermal conductivity of clay bricks. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2004, 16, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ASTM D4404-18. Standard Test Method for Determination of Pore Volume and Pore Volume Distribution of Soil and Rock by Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Standard EN ISO 10456. Building Materials and Products—Hygrothermal Properties—Tab-Ulated Design Values and Procedures for Determining Declared and DesignThermal Values. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Standard EN 1745 Masonry and masonry products-Methods for determining thermal properties. 2013; AENOR.

- Lucchi, E. Thermal transmittance of historical brick masonries: A comparison among standard data, analytical calculation procedures, and in situ heat flow meter measurements. Energy Build. 2017, 134, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E. Thermal transmittance of historical stone masonries: A comparison among standard, calculated and measured data. Energy Build. 2017, 151, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P. U-Values and Traditional Buildings; Historic Scotland Conservation Group: Glasgow, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Standard ISO 9869-1. Thermal Insulation—Building Elements –In-Situ Measurement of Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance. Part 1. Heat Flow Meter Method. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.S.; Ko, M.J. Analysis of Convergence Characteristics of Average Method Regulated by ISO 9869-1 for Evaluating In Situ Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance of Opaque Exterior Walls. Energies 2019, 12, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, D.S.; Ko, M.J. Comparison of various analysis methods based on heat flowmeters and infrared thermography measurements for the evaluation of the in situ thermal transmittance of opaque exterior walls. Energies 2017, 10, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nardi, I.; Lucchi, E.; de Rubeis, T.; Ambrosini, D. Quantification of heat energy losses through the building envelope: A state-of-the-art analysis with critical and comprehensive review on infrared thermography. Build. Environ. 2018, 146, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rotilio, M.; Cucchiella, F.; De Berardinis, P.; Stornelli, V. Thermal transmittance measurements of the historical masonries: Some case studies. Energies 2018, 11, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EnergyPlus. U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Available online: https://energyplus.net/ (accessed on 28 March 2016).

- CTE DB-HS1. Technical Building Code Basic Document-Basic Requirements Energy Saving; Ministry of Development: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: http://www.codigotecnico.org/index.php/menu-ahorro-energia (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Dell’Isola, M.; d’Ambrosio, F.R.; Giovinco, G.E.; Ianniello, E. Experimental analysis of thermal conductivity for building materials depending on moisture content. Int. J. Thermophys. 2013, 33, 1674–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, M.; Moro, L. Thermal conductivity of moist autoclaved aerated concrete: Experimental comparison between heat flow method (HFM) and transient plane source technique (TPS). Transp. Porous Media 2016, 113, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Dimensionsmm | Apparent Density kg/m3 | Porosity % | Average Pore Diameter (μm) | Water Absorption m3/m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pressed brick | 127 × 97 × 37 | 1885 | 24.05 | 0.44 | 0.241 |

| ordinary Brick | 113 × 84 × 30 | 1877 | 24.32 | 5.64 | 0.243 |

| mortar | 158 × 89 × 40 | 1825 | 28.04 | 1.04 | 0.231 |

| Material | Steam Resistivity (MNs/g) | Density kg/m3 | Specific Heat (J/kgK) | Termal Conductivity (W/mK) | Thermal Resistance (mk/W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS-CO2 Blowing | 600 | 35 | 1400 | 0.034 | 24.41 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cabeza-Prieto, A.; Camino-Olea, M.S.; Rodríguez-Esteban, M.A.; Llorente-Álvarez, A.; Pérez, M.P.S. Moisture Influence on the Thermal Operation of the Late 19th Century Brick Facade, in a Historic Building in the City of Zamora. Energies 2020, 13, 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13061307

Cabeza-Prieto A, Camino-Olea MS, Rodríguez-Esteban MA, Llorente-Álvarez A, Pérez MPS. Moisture Influence on the Thermal Operation of the Late 19th Century Brick Facade, in a Historic Building in the City of Zamora. Energies. 2020; 13(6):1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13061307

Chicago/Turabian StyleCabeza-Prieto, Alejandro, María Soledad Camino-Olea, María Ascensión Rodríguez-Esteban, Alfredo Llorente-Álvarez, and María Paz Sáez Pérez. 2020. "Moisture Influence on the Thermal Operation of the Late 19th Century Brick Facade, in a Historic Building in the City of Zamora" Energies 13, no. 6: 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13061307

APA StyleCabeza-Prieto, A., Camino-Olea, M. S., Rodríguez-Esteban, M. A., Llorente-Álvarez, A., & Pérez, M. P. S. (2020). Moisture Influence on the Thermal Operation of the Late 19th Century Brick Facade, in a Historic Building in the City of Zamora. Energies, 13(6), 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13061307