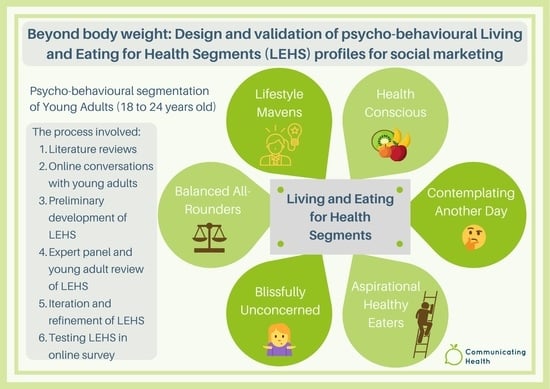

Beyond Body Weight: Design and Validation of Psycho-Behavioural Living and Eating for Health Segments (LEHS) Profiles for Social Marketing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims of the Procedure

- Sufficiently different to each other that they justify the development of a differing HP program.

- Measurable in terms of their prevalence within the population.

- Accessible in terms of being able to be effectively reached and addressed with specific HP programs.

- Substantial enough to warrant differential attention.

2.2. Instrument Development Procedure

- Formative-method: essential during the initial stages of research to establish what a construct/idea/concept is or is not (including definition and its defining characteristics).

- Formative-measure: to test whether the “real world” observations captured the abstract concept as defined in the previous stage.

- Prognosticative-method: to ensure the research process is both rigorous and consistent (where required).

- Prognosticative-measure: to establish whether a measure behaves in a way that it was expected to in relation to other constructs in a theory [33].

2.3. Literature Reviews and Formative Research

2.3.1. Literature Reviews

- A systematic review into social media use for nutrition in young adults was undertaken [34]. This review found that social media is an acceptable platform to disseminate information about healthy eating and recipes by young adults. However, social media was generally included only as one aspect of a complex intervention. Interventions as a whole (not just the social media component) had a positive statistically significant impact on nutritional outcomes in 1/9 trials. Reasons for low engagement with social media included the use of post types that are not interactive and being asked to talk about personal weight/weight loss on an open social media platform.

- In order to understand the perspectives of Indigenous Australians, a scoping review was undertaken [35]. The aim of this study was to examine the extent of health initiatives using social media that aimed to improve the health of Australian Aboriginal communities.

- A systematic review of the impact of social media on body image and nutrition found that [36] social media health-related content should refrain from focusing on body weight or physical appearance as measures of health because they are likely to alienate young adults rather than encourage behaviour change.

2.3.2. Formative Research

- A further study [37] demonstrated that social media strategies applied by influencers attract a large audience and engagement. Furthermore, HP professionals’ messages are less effective than celebrity influencers. The study found that social media, particularly Instagram, facilitates para-social interactions where imaginary social relationships and interpersonal interactions between the lifestyle personality and the social media user occur. Participants who experience positive emotions when viewing a post on social media are far more likely to engage with that post than those who do not experience positive emotions.

- Baseline exploration of aspects of the online conversations related to the language of health [38] found that young adults had a holistic view of health and that competing demands hindered their ability to realise healthy behaviours. Current healthy eating messaging did not address their needs.

- Analysis of the qualitative research [39] identified that consumer segmentation and social marketing techniques can assist health professionals to understand their target audience and tailor specific messages to different segments. Psycho-behavioural segmentation also provides unique insights on which groups may be most easily influenced to adopt the desired behaviours.

- Participants described how social media influenced their decisions to change their health behaviours [40]. Access to social support and health information through online communities were juxtaposed with exposure to highly persuasive fast-food advertising. Some participants expressed that exposure to online health content induced feelings of guilt about their behaviour, which was more prominent among females. Poor health behaviours associated with social activities and fast-food advertising were discussed as major barriers to change.

2.4. Online Conversations with Young Adults

2.5. Qualitative Thematic Analysis

- Profiles reviewed independently by research team members:

- Profiles were reviewed independently by all team members (K.K., L.B., M.R., S.C., T.A.M., M.S.L, H.T., A.M., E.J.) and disagreements were resolved via consensus in a series of single issue focus meetings.

- At this stage, semantic validity determined if there were uniform semantic usages for the profiles identified from the online conversations. The purpose of this formative-method validation is methodological.

- Expert panel review of profiles:

- Profiles were iterated based on this feedback cycle and summaries were developed that could be used in online data collection procedures (K.K., L.B.).

- Summaries were evaluated by the whole team before being tested with a sample cohort of young adults (Honours students enrolled in programs at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) and Monash University as well as two from the University of Ulster who were on placement in Australia at the time).

- Following the previous research stage, iterated profiles were further validated (prognosticative-measure). Content validity determined the degree to which the profiles can be generalised. Here, validity helped answer methodological and axiological (what is intrinsically worthwhile?) questions.

- Think Tank review and sense-check of profiles:

- Subsequent to the development of the LEHS, a Think Tank was held with the research team and partner organisations to review the findings of the online conversations and validation survey.

- The LEHS profiles were sense checked and further defined via iteration with team members and Think Tank participants. Potential ideas for evidence-based HP campaigns targeting the different LEHS and their different attitudes, behaviours, and needs were also discussed.

- This Think Tank was also used to inform further stages of the Communicating Health study, which involved the co-creation of HP campaigns with young adults [22].

- At this stage, the LEHS were then further validated to ensure that the operationalisation measures the profiles as it purports to measure (construct validity). The purpose of this formative-measure validation is an epistemological one.

2.6. Online Survey Testing LEHS

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Attitude | Attitudes are a psychological tendency expressed by evaluating an object positively or negatively. |

| Co-creation | When two or more people create something together, collaboratively and in agreement with each other about desired outcomes. Note: this is not co-production whereby the ideation may occur outside the group producing the artefact. |

| Commercial marketing | Marketing for the purposes of making profit. Marketing is the set of activities that are involved in selling products. |

| Content | Social media content takes the form of text, images, videos, and audio. It is posted on online on platforms, blogs, and wikis (see wiki). |

| Conversation | Conversations in social media are the series of interactions undertaken between participants in the system. These can be text, video, or images. People within the system (insiders) understand the language being “spoken” but outsiders may not understand the conversation. |

| Directed communication | Communication that is directed to a specific group of people for a specific purpose and which makes a direct request of the individual. For example, a social change campaign on a platform such as change.org comes via a friendship social network, has a purpose, and asks for specific action. |

| Engagement | An interaction with social media content or a post, for example, when an individual clicks “like” or “favourite” or takes the time to comment on something that has been posted, they are actively engaging with that brand’s content. |

| Exposure | The opportunity for a reader, viewer, or listener to see or hear an advertisement. |

| Identity | A person’s identity consists of who they feel they “are”. This includes ideals, beliefs, and norms. |

| Maven | A trusted expert in a particular field who seeks to pass knowledge on to others. |

| Media | The total group of communication channels used to communicate with a target audience. |

| Motivation | An unobservable inner force that stimulates and compels a behavioural response. |

| Platform | Sometimes known as a social network site or service. Examples include Pinterest, Facebook, Instagram, etc. |

| Post | Adding something to the social medium. |

| Psychographics | Factors such as personality traits, beliefs, values, lifestyles, attitudes, and interests. |

| Segmentation | The set of procedures involved in dividing a large group of people into smaller more manageable groups. Segmentation is usually undertaken by clustering people into groups based on similarities of characteristics—e.g., age, income, location of residence, attitudes, behaviours, etc. |

| Semantic analysis | Analysis that evaluates the words being used in data and assesses them against some objective criteria, e.g., patterns of usage, frequency of use, novel words, implied meanings, etc. |

| Social networking site/service | Online platforms that provide the opportunity for people to engage in social networking activities. |

| Social media | Websites and applications that enable users to create and share content or to participate in social networking. |

| Trait | An aspect of personality that is relatively stable. For example, extraversion, openness to experience, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and agreeableness. |

| Wiki | A website or database developed by a collaborative community. |

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Poirier, P.; Giles, T.D.; Bray, G.A.; Hong, Y.; Stern, J.S.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X.; Eckel, R.H. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: An update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2006, 113, 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study 2015: Interactive Data on Risk Factor Burden. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/interactive-data-risk-factor-burden/contents/overweight-and-obesity (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Townshend, T.; Lake, A. Obesogenic environments: Exploring the built and food environments. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2006, 126, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroud, C.; Walker, L.R.; Davis, M.; Irwin, C.E., Jr. Investing in the health and well-being of young adults. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Demory-Luce, D.; Morales, M.; Nicklas, T.; Baranowski, T.; Zakeri, I.; Berenson, G. Changes in food group consumption patterns from childhood to young adulthood: The Bogalusa Heart Study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilaro, M.J.; Colby, S.E.; Riggsbee, K.; Zhou, W.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Olfert, M.D.; Barnett, T.E.; Horacek, T.; Sowers, M.; Mathews, A.E. Food choice priorities change over time and predict dietary intake at the end of the first year of college among students in the US. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gordon-Larsen, P.; Nelson, M.C.; Popkin, B.M. Longitudinal physical activity and sedentary behavior trends: Adolescence to adulthood. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 27, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, W.H. Obesity and excessive weight gain in young adults: New targets for prevention. JAMA 2017, 318, 241–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella-Zarb, R.A.; Elgar, F.J. The ‘Freshman 5’: A meta-analysis of weight gain in the freshman year of college. J. Am. Coll. Health 2009, 58, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okorodudu, D.; Jumean, M.; Montori, V.M.; Romero-Corral, A.; Somers, V.; Erwin, P.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Neill, D. Measuring obesity in the absence of a gold standard. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2015, 17, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Must, A.; Spadano, J.; Coakley, E.H.; Field, A.E.; Colditz, G.; Dietz, W.H. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA 1999, 282, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, B.J.; Parrish, A.-M.; Cliff, D.P. ‘Social screens’ and ‘the mainstream’: Longitudinal competitors of non-organized physical activity in the transition from childhood to adolescence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitunen, A.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Carins, J. Segmenting Young Adult University Student’s Eating Behaviour: A Theory-Informed Approach. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ashton, L.M.; Morgan, P.J.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Rollo, M.E.; Collins, C.E. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the ‘HEYMAN’healthy lifestyle program for young men: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kattelmann, K.K.; Bredbenner, C.B.; White, A.A.; Greene, G.W.; Hoerr, S.L.; Kidd, T.; Colby, S.; Horacek, T.M.; Phillips, B.W.; Koenings, M.M. The effects of Young Adults Eating and Active for Health (YEAH): A theory-based Web-delivered intervention. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, S27–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.J.; Warren, J.M.; Lubans, D.R.; Collins, C.E.; Callister, R. Engaging men in weight loss: Experiences of men who participated in the male only SHED-IT pilot study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2011, 5, e239–e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegal, K.M.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; Carroll, M.D.; Fryar, C.D.; Ogden, C.L. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016, 315, 2284–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dhurandhar, E. The downfalls of BMI-focused policies. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 729–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lombard, C.; Brennan, L.; Reid, M.; Klassen, K.M.; Palermo, C.; Walker, T.; Lim, M.S.; Dean, M.; Mccaffrey, T.A.; Truby, H. Communicating health—Optimising young adults’ engagement with health messages using social media: Study protocol. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 75, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.; Binney, W.; Parker, L.; Aleti, T.; Nguyen, D. Social Marketing and Behaviour Change: Models, Theory and Applications; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Kubacki, K. Segmentation in Social Marketing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S.; Grün, B.; Leisch, F. Market segmentation analysis. In Market Segmentation Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kitunen, A.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Kadir, M.; Badejo, A.; Zdanowicz, G.; Price, M. Learning what our target audiences think and do: Extending segmentation to all four bases. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hollin, I.L.; Craig, B.M.; Coast, J.; Beusterien, K.; Vass, C.; DiSantostefano, R.; Peay, H. Reporting Formative Qualitative Research to Support the Development of Quantitative Preference Study Protocols and Corresponding Survey Instruments: Guidelines for Authors and Reviewers. Patient-Patient-Cent. Outcomes Res. 2020, 13, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Hagger, M.S. Psychographic profiling for effective health behavior change interventions. Front. Psychol. 2016, 6, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reid, M.; Chin, S.; Molenaar, A.; Brennan, L.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T. Learning from Social Marketing: Living and Eating for Health Segments (LEHS) and Social Media Use (P16-023-19). Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graham, M.R.; Tierney, S.; Chisholm, A.; Fox, J.R. The lived experience of working with people with eating disorders: A meta-ethnography. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 422–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, J.; Gordon, R. Strategic Social Marketing: For Behaviour and Social Change; SAGE Publications Limited: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom, D. Measuring the Mind: Conceptual Issues in Contemporary Psychometrics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, L.; Voros, J.; Brady, E. Paradigms at play and implications for validity in social marketing research. J. Soc. Mark. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, K.M.; Douglass, C.H.; Brennan, L.; Truby, H.; Lim, M.S. Social media use for nutrition outcomes in young adults: A mixed-methods systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, T.; Palermo, C.; Klassen, K. Considering the impact of social media on contemporary improvement of Australian aboriginal health: Scoping review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2019, 5, e11573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounsefell, K.; Gibson, S.; McLean, S.; Blair, M.; Molenaar, A.; Brennan, L.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T.A. Social media, body image and food choices in healthy young adults: A mixed methods systematic review. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, K.M.; Borleis, E.S.; Brennan, L.; Reid, M.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Lim, M.S. What people “like”: Analysis of social media strategies used by food industry brands, lifestyle brands, and health promotion organizations on Facebook and Instagram. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, A.; Choi, T.S.; Brennan, L.; Reid, M.; Lim, M.S.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T.A. Language of Health of Young Australian Adults: A Qualitative Exploration of Perceptions of Health, Wellbeing and Health Promotion via Online Conversations. Nutrients 2020, 12, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brennan, L.; Klassen, K.; Weng, E.; Chin, S.; Molenaar, A.; Reid, M.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T.A. A social marketing perspective of young adults’ concepts of eating for health: Is it a question of morality? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Friedman, V.; Molenaar, A.; Wright, C.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Lim, M.S. How does social media act as a persuasive format to facilitate health behaviour change in young adults? Unpublished work. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- VicHealth. Drinking-Related Lifestyles: Exploring the Role of Alcohol in Victorians’ Lives; VicHealth: Melbourne, Australia, 2013.

- The Australian Market & Social Research Society. Code of Professional Behaviour; The Australian Market & Social Research Society: Glebe, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3101.0—Australian Demographic Statistics. June 2016. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Previousproducts/3101.0Main%20Features1Jun%202016?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3101.0&issue=Jun%202016&num=&view= (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- International Organization for Standardization. The Facts about Certification. Available online: https://www.iso.org/certification.html (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Klassen, K.; Reid, M.; Brennan, L.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Truby, H.; Lim, M.; Molenaar, A. Methods—Phase 1a Online Conversations Screening and Profiling Surveys and Discussion Guide; Figshare: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Yzer, M.C. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Commun. Theor. 2003, 13, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeije, H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual. Quant. 2002, 36, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Venn, D.; Strazdins, L. Your money or your time? How both types of scarcity matter to physical activity and healthy eating. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 172, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majowicz, S.E.; Meyer, S.B.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Graham, J.L.; Shaikh, A.; Elliott, S.J.; Minaker, L.M.; Scott, S.; Laird, B. Food, health, and complexity: Towards a conceptual understanding to guide collaborative public health action. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, S.C.; Begg, D.P. Food for thought: Revisiting the complexity of food intake. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munt, A.; Partridge, S.; Allman-Farinelli, M. The barriers and enablers of healthy eating among young adults: A missing piece of the obesity puzzle: A scoping review. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatnall, M.C.; Patterson, A.J.; Chiu, S.; Oldmeadow, C.; Hutchesson, M.J. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the Eating Advice to Students (EATS) brief web-based nutrition intervention for young adult university students: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puhl, R.M.; Heuer, C.A. Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, J.M.; Major, B.; Blodorn, A.; Miller, C.T. Weighed down by stigma: How weight-based social identity threat contributes to weight gain and poor health. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2015, 9, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sarmugam, R.; Worsley, A. Dietary behaviours, impulsivity and food involvement: Identification of three consumer segments. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8036–8057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Schuster, L.; Drennan, J.; Russell-Bennett, R.; Leo, C.; Gullo, M.J.; Connor, J.P. Differential segmentation responses to an alcohol social marketing program. Addict. Behav. 2015, 49, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Leo, C.; Connor, J. One size (never) fits all: Segment differences observed following a school-based alcohol social marketing program. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Glanz, K.; Bishop, D.B. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Ann. Rev. Public Health 2010, 31, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Research | Validity | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Literature reviews and background research | Semantic (formative-method) and nomological (prognosticative-measure) | Epistemology |

| Online conversations with young adults and subsequent qualitative analysis | Observational (formative-measure) and face (formative-method) | Methodology and ontology |

| LEHS profiles reviewed independently | Semantic (formative-method) | Methodology |

| Expert panel review of LEHS profiles | Content (prognosticative-measure) | Axiology and methodology |

| Think tank review and sense-check of LEHS profiles | Construct (formative-measure) | Epistemology |

| Online survey testing LEHS | Construct (formative-measure) and nomological (prognosticative-measure) | Methodology and ontology |

| Characteristics | Categories | N (%) or Median (25th, 75th Percentiles) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18–21 years old | 109 (56%) |

| 22–24 years old | 86 (44%) | |

| Gender identity 1 | Female | 119 (61%) |

| Male | 75 (39%) | |

| Non-binary/genderfluid/genderqueer | 1 (1%) | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI, kg/m2) categories (N = 194) 2 | Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 16 (8%) |

| Healthy weight (BMI 18.5–24.9) | 106 (55%) | |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9) | 42 (22%) | |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30.0) | 30 (16%) | |

| Living location | Metro | 156 (80%) |

| Regional/rural | 39 (20%) | |

| Language other than English spoken at home/with parents | Yes | 52 (27%) |

| No | 143 (73%) | |

| Currently studying | Yes | 137 (70%) |

| No | 58 (30%) | |

| Level of current study 3 | High school, year 12 | 8 (6%) |

| TAFE, college, or diploma | 18 (13%) | |

| University (undergraduate course) | 97 (71%) | |

| University (postgraduate course) | 14 (10%) | |

| Highest level of completed education 4 | High school, year 10 or lower | 2 (3%) |

| High school, year 11 | 2 (3%) | |

| High school, year 12 | 13 (22%) | |

| TAFE, college, or diploma | 23 (40%) | |

| University (undergraduate degree) | 16 (28%) | |

| University (postgraduate degree) | 2 (3%) | |

| Living arrangements 5 | Alone | 24 (10%) |

| With their child(ren) | 18 (8%) | |

| With partner | 37 (16%) | |

| With other family | 20 (9%) | |

| With friend(s)/housemate(s) | 34 (15%) | |

| Living with parents | 97 (42%) | |

| Dispensable weekly income | Less than AU$40 | 76 (39%) |

| AU$40–$79 | 59 (30%) | |

| AU$80–$119 | 30 (15%) | |

| AU$120–$199 | 17 (9%) | |

| AU$200–$299 | 9 (5%) | |

| AU$300 or over | 3 (2%) | |

| I don’t wish to say | 1 (1%) | |

| Social media use frequency | More than twice a day | 173 (89%) |

| Twice a day | 22 (11%) | |

| Using social media to learn or talk about your health | Yes | 128 (66%) |

| No | 67 (34%) | |

| Interest in health | On a scale of 1–7, where 1 means “Strongly disagree” and 7 means “Strongly agree”, please indicate how strongly you agree with the following statement-I take an active interest in my health | 6 (5, 6) |

| Low interest in health (Below 6) | 91 (47%) | |

| Mid/high interest in health (Above 6) | 104 (53%) |

| Living and Eating for Health Segment | Profile Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Lifestyle Mavens | I’m passionate about healthy eating and health plays a big part in my life. I use social media to follow active lifestyle personalities or get new recipes/exercise ideas. I may even buy superfoods or follow a particular type of diet. I like to think I am super healthy. |

| Health Conscious | I’m health-conscious and being healthy and eating healthy is important to me. Although health means different things to different people, I make conscious lifestyle decisions about eating based on what I believe healthy means. I look for new recipes and healthy eating information on social media. |

| Aspirational Healthy Eaters | I aspire to be healthy (but struggle sometimes). Healthy eating is hard work! I’ve tried to improve my diet, but always find things that make it difficult to stick with the changes. Sometimes I notice recipe ideas or healthy eating hacks, and if it seems easy enough, I’ll give it a go. |

| Balanced All Rounders | I try and live a balanced lifestyle, and I think that all foods are okay in moderation. I shouldn’t have to feel guilty about eating a piece of cake now and again. I get all sorts of inspiration from social media like finding out about new restaurants, fun recipes and sometimes healthy eating tips. |

| Contemplating Another Day | I’m contemplating healthy eating but it’s not a priority for me right now. I know the basics about what it means to be healthy, but it doesn’t seem relevant to me right now. I have taken a few steps to be healthier but I am not motivated to make it a high priority because I have too many other things going on in my life. |

| Blissfully Unconcerned | I’m not bothered about healthy eating. I don’t really see the point and I don’t think about it. I don’t really notice healthy eating tips or recipes and I don’t care what I eat. |

| Characteristic | Category | Lifestyle Mavens n311 (15.4%) | Health Conscious n425 (21.1%) | Aspirational Healthy Eaters n556 (27.5%) | Balanced All Rounders n432 (21.4%) | Contemplating Another Day n226 (11.2%) | Blissfully Unconcerned n69 (3.4%) | p Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 21 (2) 2 | 21 (2) | 21 (2) | 21 (2) | 21 (2) | 20 (2) | 0.103 | |

| Gender | Male | 193 (62.1%) 3 | 228 (53.6%) | 197 (35.4%) | 150 (34.7%) | 99 (43.8%) | 39 (56.5%) | <0.001 |

| Female | 112 (36.0%) | 185 (43.5%) | 339 (61.0%) | 268 (62.0%) | 117 (51.8%) | 25 (36.2%) | ||

| Non-binary/genderfluid/genderqueer/transgender | 5 (1.6%) | 11 (2.6%) | 19 (3.4%) | 14 (3.2%) | 9 (4.0%) | 4 (5.8%) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.002%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.004%) | 1 (1.4%) | ||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 24.6 (5.9) a,d,e | 23.4 (4.9) a | 26.0 (6.7) c | 23.7 (4.9) a,b | 25.4 (6.3) c,d | 26.3 (7.3) b,c,e | <0.001 | |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 28 (9.0%) | 42 (9.9%) | 37 (6.7%) | 41 (9.5%) | 16 (7.1%) | 9 (13.0%) | ||

| Healthy weight (BMI 18.5–24.9) | 171 (55.0%) | 275 (64.7%) | 260 (46.8%) | 254 (58.8%) | 111 (49.1%) | 30 (43.5%) | ||

| Overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9) | 72 (23.2%) | 76 (17.9%) | 145 (26.1%) | 87 (20.1%) | 53 (23.5%) | 13 (18.8%) | ||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30.0) | 40 (12.9%) | 32 (7.5%) | 114 (20.5%) | 50 (11.6%) | 46 (20.4%) | 17 (24.6%) | ||

| Currently studying | Yes | 171 (55.0%) | 237 (55.8%) | 297 (53.4%) | 238 (55.1%) | 132 (58.4%) | 26 (37.7%) | 0.016 |

| No | 129 (41.5%) | 180 (42.4%) | 248 (44.6%) | 185 (42.8%) | 86 (38.1%) | 37 (53.6%) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 11 (3.5%) | 8 (1.9%) | 11 (2.0%) | 9 (2.1%) | 8 (3.5%) | 6 (8.7%) | ||

| Weekly income | No income | 24 (7.7%) | 57 (13.4%) | 59 (10.6%) | 40 (18.1%) | 40 (17.7%) | 11 (15.9%) | <0.001 |

| $1–$399 | 89 (28.6%) | 114 (26.8%) | 176 (31.7%) | 71 (30.3%) | 71 (31.4%) | 30 (43.5%) | ||

| $400–$649 | 39 (12.5%) | 66 (15.5%) | 96 (17.3%) | 28 (13.9%) | 28 (12.4%) | 7 (10.1%) | ||

| $650–$999 | 54 (17.4%) | 59 (13.9%) | 90 (16.2%) | 34 (15.7%) | 34 (15.0%) | 6 (8.7%) | ||

| $1000–$1499 | 46 (14.8%) | 63 (14.8%) | 46 (8.3%) | 23 (10.0%) | 23 (10.2%) | 7 (10.1%) | ||

| $1500–over $3000 | 47 (15.1%) | 45 (10.6%) | 47 (8.5%) | 14 (4.4%) | 14 (6.2%) | 3 (4.3%) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 12 (3.9%) | 21 (4.9%) | 42 (7.6%) | 16 (7.6%) | 16 (7.1%) | 5 (7.2%) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brennan, L.; Chin, S.; Molenaar, A.; Barklamb, A.M.; Lim, M.S.; Reid, M.; Truby, H.; Jenkins, E.L.; McCaffrey, T.A. Beyond Body Weight: Design and Validation of Psycho-Behavioural Living and Eating for Health Segments (LEHS) Profiles for Social Marketing. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092882

Brennan L, Chin S, Molenaar A, Barklamb AM, Lim MS, Reid M, Truby H, Jenkins EL, McCaffrey TA. Beyond Body Weight: Design and Validation of Psycho-Behavioural Living and Eating for Health Segments (LEHS) Profiles for Social Marketing. Nutrients. 2020; 12(9):2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092882

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrennan, Linda, Shinyi Chin, Annika Molenaar, Amy M. Barklamb, Megan SC Lim, Mike Reid, Helen Truby, Eva L. Jenkins, and Tracy A. McCaffrey. 2020. "Beyond Body Weight: Design and Validation of Psycho-Behavioural Living and Eating for Health Segments (LEHS) Profiles for Social Marketing" Nutrients 12, no. 9: 2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092882

APA StyleBrennan, L., Chin, S., Molenaar, A., Barklamb, A. M., Lim, M. S., Reid, M., Truby, H., Jenkins, E. L., & McCaffrey, T. A. (2020). Beyond Body Weight: Design and Validation of Psycho-Behavioural Living and Eating for Health Segments (LEHS) Profiles for Social Marketing. Nutrients, 12(9), 2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092882