Maternal Folate Status and the BHMT c.716G>A Polymorphism Affect the Betaine Dimethylglycine Pathway during Pregnancy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Participants

2.2. Blood Sample Collection and Biochemical and Genetic Determinations

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

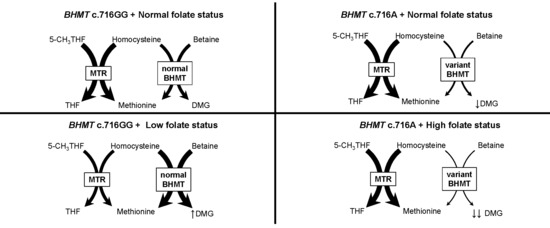

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies and Interpretation

4.3. Implications

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McKeever, M.P.; Weir, D.G.; Molloy, A.; Scott, J.M. Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase: Organ distribution in man, pig and rat and subcellular distribution in the rat. Clin. Sci. 1991, 81, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, J.D.; Martin, J.J. Methionine metabolism in mammals. Distribution of homocysteine between competing pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 9508–9513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, J.D. Methionine metabolism in mammals. J. Nutr. Biochem. 1990, 1, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, B.D.; Titgemeyer, E.C.; Stokka, G.L.; DeBey, B.M.; Löest, C.A. Methionine supply to growing steers affects hepatic activities of methionine synthase and betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase, but not cystathionine synthase. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 2004–2009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaull, G.E.; Von Berg, W.; Räihä, N.C.; Sturman, J.A. Development of methyltransferase activities of human fetal tissues. Pediatr. Res. 1973, 7, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sunden, L.F.; Renduchintala, M.S.; Park, E.I.; Miklasz, S.D.; Garrow, T.A. Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase expression in porcine and human tissues and chromosomal localization of the human gene. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997, 345, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melse-Boonstra, A.; Holm, P.I.; Ueland, P.M.; Olthof, M.; Clarke, R.; Verhoef, P. Betaine concentration as a determinant of fasting total homocysteine concentrations and the effect of folic acid supplementation on betaine concentrations. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 1378–1382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Imbard, A.; Smulders, Y.M.; Barto, R.; Smith, D.E.C.; Kok, R.M.; Jakobs, C.; Blom, H.J. Plasma choline and betaine correlate with serum folate, plasma S-adenosyl-methionine and S-adenosyl-homocysteine in healthy volunteers. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2013, 51, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.H.; Stabler, S.P.; Lindenbaum, J. Serum betaine, N,N-dimethylglycine and N-methylglycine levels in patients with cobalamin and folate deficiency and related inborn errors of metabolism. Metabolism 1993, 42, 1448–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, P.I.; Ueland, P.M.; Vollset, S.E.; Midttun, Ø.; Blom, H.J.; Keijzer, M.B.; den Heijer, M. Betaine and folate status as cooperative determinants of plasma homocysteine in humans. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, P.I.; Bleie, Ø.; Ueland, P.M.; Lien, E.; Refsum, H.; Nordrehaug, J.E.; Nygård, O. Betaine as a determinant of postmethionine load total plasma homocysteine before and after B-vitamin supplementation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernàndez-Roig, S.; Cavallé-Busquets, P.; Fernandez-Ballart, J.D.; Ballesteros, M.; Berrocal-Zaragoza, M.I.; Salat-Batlle, J.; Ueland, P.M.; Murphy, M.M. Low folate status enhances pregnancy changes in plasma betaine and dimethylglycine concentrations and the association between betaine and homocysteine. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1252–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.I.; Garrow, T. Interaction between dietary methionine and methyl donor intake on rat liver betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase gene expression and organization of the human gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 7816–7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heil, S.G.; Lievers, K.J.; Boers, G.H.; Verhoef, P.; den Heijer, M.; Trijbels, F.J.; Blom, H.J. Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT): Genomic sequencing and relevance to hyperhomocysteinemia and vascular disease in humans. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2000, 71, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisberg, I.S.; Park, E.; Ballman, K.V.; Berger, P.; Nunn, M.; Suh, D.S.; Breksa, A.P.; Garrow, T.A.; Rozen, R. Investigations of a common genetic variant in betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT) in coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2003, 167, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth, C.V.; Elsasser, D.; Kinzler, W.L.; Peltier, M.R.; Getahun, D.; Leclerc, D.; Rozen, R.R. Polymorphisms in methionine synthase reductase and betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase genes: Risk of placental abruption. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007, 91, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredriksen, A.; Meyer, K.; Ueland, P.M.; Vollset, S.E.; Grotmol, T.; Schneede, J. Large-scale population-based metabolic phenotyping of thirteen genetic polymorphisms related to one-carbon metabolism. Hum. Mutat. 2007, 28, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Qian, Y.; Ma, D.; Tian, W.; Persaud-Sharma, V.; Yu, C.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, S.; et al. The effect of multiple single nucleotide polymorphisms in the folic acid pathway genes on homocysteine metabolism. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 560183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Qi, J.; Yu, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Ning, Q.; Luo, X. Investigations of single nucleotide polymorphisms in folate pathway genes in Chinese families with neural tube defects. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 337, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, G.M.; Lu, W.; Zhu, H.; Yang, W.; Briggs, F.B.S.; Carmichael, S.L.; Barcellos, L.F.; Lammer, E.J.; Finnell, R.H. 118 SNPs of folate-related genes and risks of spina bifida and conotruncal heart defects. BMC Med. Genet. 2009, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyles, A.L.; Billups, A.V.; Deak, K.L.; Siegel, D.G.; Mehltretter, L.; Slifer, S.H.; Bassuk, A.G.; Kessler, J.A.; Reed, M.C.; Nijhout, H.F.; et al. Neural tube defects and folate pathway genes: Family-based association tests of gene-gene and gene-environment interactions. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 1547–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostowska, A.; Hozyasz, K.K.; Wojcicki, P.; Dziegelewska, M.; Jagodzinski, P.P. Associations of folate and choline metabolism gene polymorphisms with orofacial clefts. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 47, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampieri, B.L.; Biselli, J.M.; Goloni-Bertollo, E.M.; Vannucchi, H.; Carvalho, V.M.; Cordeiro, J.A.; Pavarino, E.C. Maternal risk for Down syndrome is modulated by genes involved in folate metabolism. Dis. Markers 2012, 32, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, M.R.; Moura, C.M.; Gomes, A.D.; Barboza, H.N.; Lopes, R.B.; Ribeiro, M.G.; Costa Lima, M.A. Betaine–homocysteine methyltransferase 742G>A polymorphism and risk of down syndrome offspring in a Brazilian population. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 4685–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Dardet, C.; Alonso, J.; Domingo, A.; Regidor, E. La Medición de la Clase Social en Ciencias de la Salud; SG Editores, SEE: Barcelona, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dirección General de Salud Pública (Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo—Gobierno de España). Recomendaciones Sobre Suplementación con ácido Fólico para la Prevención de Defectos del Tubo Neural; Dirección General de Salud Pública: Madrid, Spain, 2001; Volume 25.

- Molloy, A.M.; Scott, J.M. Microbiological assay for serum, plasma, and red cell folate using cryopreserved, microtiter plate method. Methods Enzymol. 1997, 281, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holm, P.I.; Ueland, P.M.; Kvalheim, G.; Lien, E.A. Determination of choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine in plasma by a high-throughput method based on normal-phase chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueland, P.M.; Midttun, O.; Windelberg, A.; Svardal, A.; Skålevik, R.; Hustad, S. Quantitative profiling of folate and one-carbon metabolism in large-scale epidemiological studies by mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2007, 45, 1737–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midttun, Ø.; Hustad, S.; Ueland, P.M. Quantitative profiling of biomarkers related to B-vitamin status, tryptophan metabolism and inflammation in human plasma by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2009, 23, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.; Fredriksen, A.; Ueland, P.M. High-level multiplex genotyping of polymorphisms involved in folate or homocysteine metabolism by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2004, 50, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Serum and Red Blood Cell Folate Concentrations for Assessing Folate Status in Populations. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. 2012. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75584/1/WHO_NMH_NHD_EPG_12.1_eng.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2016).

- Giusti, B.; Sestini, I.; Saracini, C.; Sticchi, E.; Bolli, P.; Magi, A.; Gori, A.M.; Marcucci, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Abbate, R. High-throughput multiplex single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis in genes involved in methionine metabolism. Biochem. Genet. 2008, 46, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, C.; Breksa, A.P.; Salisbury, E.; Garrow, T.A. Betaine-Homocysteine S-Methyltransferase (BHMT) Transcription Is Inhibited by S-Adenosylmethionine (ADOMET). In Chemistry and Biology of Pteridines and Folates; Milstien, S., Kapatos, G., Levine, R.A., Shane, B., Eds.; Springer: Bethesda, Spain, 2002; pp. 549–556. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, X.; Yang, H.; Ramani, K.; Ara, A.I.; Chen, H.; Mato, J.M.; Lu, S.C. Inhibition of human betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase expression by S-adenosylmethionine and methylthioadenosine. Biochem. J. 2007, 401, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, J.D.; Martin, J.J. Inactivation of betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase by adenosylmethionine and adenosylethionine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984, 118, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, J.D.; Kyle, W.E.; Harris, B.J. Methionine metabolism in mammals: Regulatory effects of S-adenosylhomocysteine. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1974, 165, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, J.D.; Harris, B.J.; Kyle, W.E. Methionine metabolism in mammals: Kinetic study of betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1972, 153, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedi, S.S.; Castro, C.C.; Koutmos, M.; Garrow, T.A. Betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase-2 is an S-methylmethionine-homocysteine methyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 8939–8945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, K.E.; Mikael, L.G.; Leung, K.Y.; Lévesque, N.; Deng, L.; Wu, Q.; Malysheva, O.V.; Best, A.; Caudill, M.A.; Greene, N.D.; et al. High folic acid consumption leads to pseudo-MTHFR deficiency, altered lipid metabolism, and liver injury in mice. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmurzynska, A.; Malinowska, A.M. Homocysteine homeostasis in the rat is maintained by compensatory changes in cystathionine β-synthase, betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase, and phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase gene transcription occurring in response to maternal protein and folic acid intake during pregnancy and fat intake after weaning. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eussen, S.J.P.M.; Ueland, P.M.; Clarke, R.; Blom, H.J.; Hoefnagels, W.H.L.; van Staveren, W.; de Groot, L.C.P.G.M. The association of betaine, homocysteine and related metabolites with cognitive function in Dutch elderly people. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Salas, P.; Moore, S.E.; Cole, D.; da Costa, K.A.; Cox, S.E.; Dyer, R.A.; Fulford, A.J.C.; Innis, S.M.; Waterland, R.A.; Zeisel, S.H.; et al. DNA methylation potential: dietary intake and blood concentrations of one-carbon metabolites and cofactors in rural African women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancey, P.H.; Clark, M.E.; Hand, S.C.; Bowlus, R.D.; Somero, G.N. Living with water stress: Evolution of osmolyte systems. Science 1982, 217, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh-Hamad, D.; García-Pérez, A.; Ferraris, J.D.; Peters, E.M.; Burg, M.B. Induction of gene expression by heat shock versus osmotic stress. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 267, F28–F34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q.; Kalari, K.; Fridley, B.L.; Jenkins, G.; Ji, Y.; Abo, R.; Hebbring, S.; Zhang, J.; Nye, M.D.; Leeder, J.S.; et al. Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase: Human liver genotype-phenotype correlation. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2011, 102, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganu, R.; Garrow, T.; Koutmos, M.; Rund, L.; Schook, L.B. Splicing variants of the porcine betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase gene: Implications for mammalian metabolism. Gene 2013, 529, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.M.; Fernandez-Ballart, J.D. Homocysteine in pregnancy. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2011, 53, 105–137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.M.; Fernandez-Ballart, J.D.; Molloy, A.M.; Canals, J. Moderately elevated maternal homocysteine at preconception is inversely associated with cognitive performance in children 4 months and 6 years after birth. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collinsova, M.; Strakova, J.; Jiracek, J.; Garrow, T.A. Inhibition of betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase causes hyperhomocysteinemia in mice. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1493–1497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.M.; Scott, J.M.; McPartlin, J.M.; Fernandez-Ballart, J.D. The pregnancy-related decrease in fasting plasma homocysteine is not explained by folic acid supplementation, hemodilution, or a decrease in albumin in a longitudinal study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E.; Jacques, P.F.; Dougherty, L.; Selhub, J.; Giovannucci, E.; Zeisel, S.H.; Cho, E. Are dietary choline and betaine intakes determinants of total homocysteine concentration? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiskerstrand, T.; Refsum, H.; Kvalheim, G.; Ueland, P.M. Homocysteine and other thiols in plasma and urine: Automated determination and sample stability. Clin. Chem. 1993, 39, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Age (Year) 1 | 32.0 (29.0, 35.0) | |

|---|---|---|

| Body mass index (kg/m2) 1 | 23.0 (20.9, 25.4) | |

| Planned pregnancy 2 | 80.9 (77.3, 84.0) | |

| Previous pregnancy 2 | 52.6 (48.6, 56.5) | |

| Socioeconomic status 2,3 | High | 43.6 (39.6, 47.6) |

| Mid | 49.6 (45.5, 53.6) | |

| Low | 6.8 (5.1, 9.1) | |

| Smoking during pregnancy 2 | First trimester | 28.1 (24.7, 31.8) |

| Throughout pregnancy | 17.0 (14.2, 20.3) | |

| Folic acid supplement use 2 | Preconception | 34.1 (30.2, 38.2) |

| First trimester | 93.8 (91.5, 95.4) | |

| Mid-late pregnancy | 53.9 (49.6, 58.1) | |

| BHMT c.716G>A 2 | GG | 48.9 (45.0, 52.9) |

| GA | 40.5 (36.6, 44.4) | |

| AA | 10.6 (8.4, 13.3) |

| BHMT c.716G>A Genotype | ≤12 GW [546] 1 | 15 GW [440] | 24–27 GW [500] | 34 GW [485] | Labour [478] | Cord [465] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folate (nmol/L) | GG | 26.8 (24.5, 29.2) | 25.6 (23.3, 28.1) | 13.3 a (12.2, 14.6) | 10.9 a (9.9, 12.1) | 10.8 a (9.7, 11.9) | 23.9 (22.2, 25.7) |

| GA | 25.5 (23.2, 28.0) | 24.6 (22.3, 27.1) | 12.9 a (11.7, 14.2) | 10.7 a (9.7, 11.9) | 10.8 a (9.7, 12.1) | 24.2 (22.4, 26.1) | |

| AA | 24.5 (20.2, 29.6) | 25.4 (20.8, 31.1) | 12.6 a (10.3, 15.3) | 12.0 a (9.6, 15.1) | 10.2 a (8.2, 12.9) | 22.6 (19.1, 26.6) | |

| ANCOVA 3 models | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| Choline (µmo/L) | GG | 7.6 (7.4, 7.9) | 7.7 (7.5, 7.9) | 9.1 a (8.9, 9.4) | 10.3 a (10.1, 10.6) | 11.7 a (11.3, 12.1) | 28.1 (26.8, 29.5) |

| GA | 7.7 (7.4, 7.9) | 7.7 (7.5, 8.0) | 9.2 a (9.0, 9.5) | 10.4 a (10.1, 10.7) | 11.7 a (11.3, 12.2) | 28.9 (27.5, 30.4) | |

| AA | 7.6 (7.2, 8.1) | 8.0 (7.5, 8.5) | 9.5 a (9.0, 10.1) | 10.5 a (9.9, 11.2) | 11.6 a (10.7, 12.5) | 29.8 (26.8, 33.1) | |

| ANCOVA 3 models | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| Betaine (µmol/L) | GG | 20.9 (20.2, 21.6) | 14.6 a (14.2, 15.1) | 12.8 a (12.4, 13.1) | 12.8 a (12.5, 13.1) | 13.1 a (12.7, 13.5) | 24.7 (24.0, 25.4) |

| GA | 21.8 (21.0, 22.6) | 15.3 a (14.8, 15.8) | 13.1 a (12.7, 13.4) | 13.3 a (12.9, 13.7) | 13.4 a (13.0, 13.8) | 25.1 (24.3, 25.8) | |

| AA | 20.2 (18.8, 21.8) | 14.5 a (13.6, 15.5) | 12.7 a (11.9, 13.4) | 13.0 a (12.3, 13.8) | 12.7 a (11.9, 13.5) | 25.3 (23.8, 27.0) | |

| ANCOVA3 models | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| Dimethylglycine (µmol/L) | GG | 2.58 (2.47, 2.69) | 2.29 a (2.19, 2.39) | 2.22 a (2.12, 2.33) | 2.51 (2.39, 2.64) | 3.00 a (2.84, 3.18) | 3.73 (3.55, 3.92) |

| GA | 2.37 (2.26, 2.48) * | 2.12 a (2.02, 2.22) | 2.11 a (2.00, 2.22) | 2.39 (2.27, 2.52) | 2.69 a (2.53, 2.86) * | 3.54 (3.36, 3.73) | |

| AA | 2.50 (2.28, 2.74) | 2.08 a (1.88, 2.30) | 2.02 a (1.82, 2.24) | 2.01 a (1.79, 2.25) **,† | 2.44 (2.16, 2.76) ** | 3.29 (2.95, 3.67) | |

| ANCOVA 4 models | p = 0.026 | p = 0.040 | NS | p = 0.002 | p = 0.002 | NS | |

| Folate genotype interaction | p = 0.023 | p = 0.058 | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| Dimethylglycine/betaine | GG | 0.13 (0.12, 0.14) | 0.17 a (0.16, 0.18) | 0.19 a (0.18, 0.21) | 0.22 a (0.20, 0.24) | 0.26 a (0.23, 0.28) | 0.17 (0.15, 0.18) |

| GA | 0.12 (0.11, 0.13) | 0.15 a (0.14, 0.16) * | 0.18 a (0.16, 0.19) | 0.20 a (0.18, 0.22) | 0.23 a (0.21, 0.26) | 0.15(0.14, 0.16) | |

| AA | 0.15 (0.13, 0.17) † | 0.15 (0.13, 0.17) | 0.18 a (0.15, 0.22) | 0.16 (0.12, 0.20) * | 0.22 a (0.17, 0.27) | 0.14 (0.11, 0.16) | |

| ANCOVA 5 models | p = 0.009 | p = 0.018 | NS | p = 0.020 | NS | p = 0.044 | |

| Folate genotype interaction | p = 0.038 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| Total homocysteine (µmol/L) | GG | 5.2 (5.1, 5.4) | 4.5 a (4.4, 4.7) | 4.6 a (4.5, 4.8) | 5.3 (5.1, 5.4) | 6.2 a (6.0, 6.5) | 4.8 (4.7, 5.0) |

| GA | 5.3 (5.1, 5.4) | 4.4 a (4.3, 4.6) | 4.7 a (4.5, 4.8) | 5.4 (5.2, 5.6) | 6.2 a (5.9, 6.4) | 4.9 (4.7, 5.2) | |

| AA | 5.3 (5.0, 5.6) | 4.5 a (4.3, 4.8) | 4.6 a (4.3, 4.9) | 5.2 (4.9, 5.6) | 6.0 a (5.6, 6.5) | 4.9 (4.5, 5.3) | |

| ANCOVA 4 models | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Model 1 | Plasma Folate Category 2 | BHMT c.716G>A Genotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | F (n) | Possibly deficient vs. normal-high | GA vs. GG | AA vs. GG | ||

| Early | ≤12 GW | 15.4 | 22.5 (592) *** | 0.07 (0.04) 3,* | −0.08 (0.03) ** | −0.04 (0.05) |

| 15 GW | 12.0 | 12.6 (427) *** | 0.07 (0.04) # | −0.08 (0.03) * | −0.11 (0.06) † | |

| Mid-late | 24–27 GW | 11.6 | 14.3 (507) *** | 0.13 (0.03) *** | −0.06 (0.04) | −0.10 (0.06) |

| 34 GW | 18.9 | 23.8 (492) *** | 0.20 (0.04) *** | −0.06 (0.04) | −0.23 (0.06) *** | |

| Labour | 13.2 | 15.5 (477) *** | 0.15 (0.04) *** | −0.11 (0.04) * | −0.21 (0.07) ** | |

| Cord | 5.0 | 5.7 (447) *** | 0.08 (0.04) * | −0.05 (0.04) * | −0.13 (0.06) * | |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Colomina, J.M.; Cavallé-Busquets, P.; Fernàndez-Roig, S.; Solé-Navais, P.; Fernandez-Ballart, J.D.; Ballesteros, M.; Ueland, P.M.; Meyer, K.; Murphy, M.M. Maternal Folate Status and the BHMT c.716G>A Polymorphism Affect the Betaine Dimethylglycine Pathway during Pregnancy. Nutrients 2016, 8, 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8100621

Colomina JM, Cavallé-Busquets P, Fernàndez-Roig S, Solé-Navais P, Fernandez-Ballart JD, Ballesteros M, Ueland PM, Meyer K, Murphy MM. Maternal Folate Status and the BHMT c.716G>A Polymorphism Affect the Betaine Dimethylglycine Pathway during Pregnancy. Nutrients. 2016; 8(10):621. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8100621

Chicago/Turabian StyleColomina, Jose M., Pere Cavallé-Busquets, Sílvia Fernàndez-Roig, Pol Solé-Navais, Joan D. Fernandez-Ballart, Mónica Ballesteros, Per M. Ueland, Klaus Meyer, and Michelle M. Murphy. 2016. "Maternal Folate Status and the BHMT c.716G>A Polymorphism Affect the Betaine Dimethylglycine Pathway during Pregnancy" Nutrients 8, no. 10: 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8100621

APA StyleColomina, J. M., Cavallé-Busquets, P., Fernàndez-Roig, S., Solé-Navais, P., Fernandez-Ballart, J. D., Ballesteros, M., Ueland, P. M., Meyer, K., & Murphy, M. M. (2016). Maternal Folate Status and the BHMT c.716G>A Polymorphism Affect the Betaine Dimethylglycine Pathway during Pregnancy. Nutrients, 8(10), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8100621